In the 1950s, at the onset of the Cold War, Pakistan and Turkey were part of the Central Treaty Organization or CENTO, a pro-Western bloc of Muslim-majority states. Today, the two countries — both with troubled relations with the United States — are Muslim middle powers with a growing entente in a multipolar Eurasia.

In recent years, cooperation between Pakistan and Turkey has strengthened not just in the defense, diplomatic, and economic realms, but also in the cultural space, causing geopolitical ripple effects in the Himalayas, the Arabian Peninsula, and the South Caucasus.

The emerging Pakistan-Turkey entente now has the buy-in of Pakistan’s leading political parties and three military services, as well as the Turkish leadership. The partnership aids and, at times, complicates the quest of both countries for strategic autonomy as options in the West narrow. However, the potential of the Pakistani-Turkish entente will be constrained by the economic precarity of the two countries and the limited prospects for growth in trade in the near term.

Brothers in arms

On Jan. 23, at a ceremony for Turkish-built naval vessels, including a corvette for the Pakistan Navy, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan spoke of the “great potential” for defense industrial cooperation between Pakistan and Turkey, which he described as “brotherly countries.”

Indeed, as its domestic arms industry has grown rapidly, so too has the profile of Ankara’s defense deals with Islamabad, quickly shifting from the upgrading of Pakistani hardware originally procured from other NATO countries — American F-16s and French Agosta 90-B subs — to the sale of arms made in Turkey.

Turkish arms transfers to Pakistan totaled $112 million from 2016-2019, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). During this period, Turkey was Pakistan's fourth-largest source of arms, surpassing the United States, and Pakistan was Turkey’s third-largest arms export market, according to SIPRI. These numbers will grow as Turkey fulfills recent orders from Pakistan exceeding $3 billion, including the purchase of four MILGEM Ada-class corvettes, two of which will be built in Pakistan, and 30 T-129 Atak helicopters.

Pakistani and Turkish aspirations for defense autarky were both born from bitter experiences of being sanctioned by the West. Continued Western compellence also drives — and problematizes — Pakistan-Turkey defense cooperation. The T-129 helicopter deal has been in limbo as Congress has blocked export licenses to Turkey for its American-British designed LHTEC T800-4A turboshaft engine. Turkey is developing a replacement for the T800-4A, the TEI TS1400, which could salvage the deal should U.S.-Turkey relations remain cold. But the TS1400 is currently in the prototype stage — years away from service.

While China will remain Pakistan’s main source of imported defense hardware, Turkey too provides an alternative to increasingly inaccessible American and French equipment, and modestly eases Islamabad’s dependence on Beijing. The T-129s are intended to replace Pakistan’s aging fleet of American AH-1F Cobras. Pakistan has also purchased Turkish armaments for its JF-17 fighter jet, jointly manufactured with China.

Pakistan-Turkey defense relations go beyond purchases of Turkish arms by Islamabad. Ankara has procured training aircraft, drone parts, and bombs from Islamabad. And the two countries are also increasingly pursuing technological cooperation. The MILGEM Ada-class ship deal, for example, involves the transfer of technology. Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI) has also secured an agreement with Pakistan’s premier engineering school, the National University of Science and Technology, for research and development cooperation and faculty and student exchanges. TAI has also agreed to set up shop at Pakistan’s National Science and Technology Park, a section of which will focus on defense projects, including cyberwarfare, drones, and radar technology.

A diplomatic bloc

Earlier in January, Azerbaijan, Pakistan, and Turkey held the second round of foreign minister-level trilateral talks in Islamabad, issuing a joint statement reflecting alignment on the disputes in Cyprus, Kashmir, and Nagorno-Karabakh.

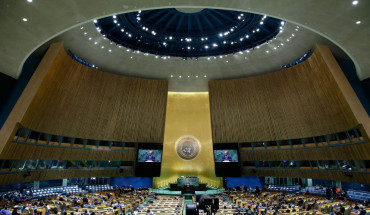

Azerbaijan and Pakistan have for some time sided with one another on their main territorial disputes. And Turkey has long been a supporter of Azerbaijani sovereignty over Nagorno-Karabakh. But Turkey’s embrace of the Kashmiri cause is relatively new. In recent years, Erdoğan has vocally advocated a negotiated settlement to the Kashmir conflict, including at the U.N. General Assembly, where he called for the dispute to be resolved “within the framework of the U.N. resolutions” and “in line with the expectations of the people of Kashmir.”

Erdoğan’s language has angered New Delhi, which bristles at any outside attempt to internationalize the Kashmir dispute. And Erdoğan has won hearts in Pakistan, which has struggled to gain diplomatic support, including from Muslim-majority countries, for its position on Kashmir.

Driven in part by a desire to expand ties with New Delhi, a leading energy importer, Abu Dhabi and Riyadh have distanced themselves from support for the Kashmiri cause. But Pakistan, particularly after India’s effective annexation of Kashmir in 2019, sees Kashmir as an existential issue. As a result, it has doubled down on alignment with Turkey, even initially partnering with Iran, Malaysia, and Turkey to hold an Islamic summit in Kuala Lumpur in December 2019. This angered Abu Dhabi and Riyadh, resulting in Islamabad backing out of the summit. Despite Pakistan’s compliance, months later, after Erdoğan’s state visit to Islamabad, Saudi Arabia asked Pakistan to repay short-term loans meant to bolster its precarious foreign exchange reserves.

The Turkish-Pakistani bloc has also ruffled feathers elsewhere. In October, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan gave an interview with an Indian news channel partly owned by a member of the country’s Hindu nationalist ruling party and, without evidence, accused Pakistan of sending mercenaries to Nagorno-Karabakh.

A culture of Muslim nationalism

Turkey’s diplomatic reach into Pakistan extends into the soft power space as well. An Urdu-language version of the series, “Diriliş: Ertuğrul,” which chronicles the rise of the father of the founder of the Ottoman Empire, is a hit in Pakistan.

The Turkish state television-produced show airs in primetime on the state-run Pakistan Television. Views of its first episode on YouTube alone exceed 90 million and the show’s Turkish cast members are now celebrities in Pakistan. The success of “Ertuğrul” has spurred discussions between the two countries on the development of a new series, “Turk Lala,” profiling a man from present-day Pakistan who migrated to Turkey in 1920 and fought in support of the embattled Ottoman Empire.

Muslim nationalism, both as a contemporary sentiment and a historical narrative, now colors a relationship rooted in realpolitik.

The road ahead: Vulnerable economies

Alongside rising arms sales, Turkish economic investment in Pakistan has grown in the past decade. Turkish foreign direct investment in Pakistan since 2009 has exceeded $300 million. Zorlu Energy, a Turkish company, has constructed a series of renewable independent power projects. In 2016, Arçelik, the home appliance subsidiary of the Turkish conglomerate Koç Holding, bought the Pakistani company Dawlance for $258 million. Lahore’s waste management has also been outsourced to two Turkish companies since 2012.

While Turkish investment in Pakistan has risen, bilateral trade between the two countries has remained stagnant over the past decade, peaking at around $1.1 billion in 2011, according to U.N. Comtrade, partly due to Ankara’s protectionism. Talks over a free trade agreement have also stalled.

Late last year, Turkey’s transport minister said that a rail line connecting Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey could become operational in 2021. But policies that inhibit trade and the abysmal state of Pakistan’s rail network will have to be addressed for their economic connectivity aspirations to go beyond rhetoric.

Pakistan and Turkey have rapidly formed a strategic partnership in recent years amid a very fluid global order. The two countries share important elements of national power — strong militaries, strategic locations, and sizeable populations — that will drive defense, diplomatic, and technological cooperation in the years to come.

But the two countries also share some vulnerabilities: their economies are in their worst shape in two decades and both countries are net energy importers. In the case of Pakistan, the structural economic weaknesses are far more deep: chief among them, the dismal state of human development.

For both Pakistan and Turkey to succeed in their respective quests for strategic autonomy and leverage their partnership into firm geostrategic gains, sustained economic growth is absolutely essential.

Arif Rafiq is the president of Vizier Consulting LLC, a political risk advisory company focused on the Middle East and South Asia, and a non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by Emrah Yorulmaz/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.