Are religious doctrinal differences primarily responsible for stoking intercommunal fear and hatred? What roles have state, sub-state and transnational actors played in fomenting sectarian discord? And what could be done to avert sectarian violence, to foster tolerance and peaceful coexistence, and to promote reconciliation? The essays in this series tackle these and other salient questions pertaining to sectarianism in the MENA and Asia Pacific regions. Read more ...

Burma’s Ethnic Cleansing in the Social Media

In the age of Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, netizens around the world view on their mobile phones and tablets the deeply disturbing images of Rohingyas, children, elderly men and women, filing out of Western Burma (or Myanmar) as the result of Burma military’s “clearance operations”[1] at the rate of 100,000 per week[2] for 6 weeks. The power of such imagery has so moved national politicians and senior officials from such world bodies as UN and EU that they have publicly used such evocative, if non-legal term as “ethnic cleansing”.[3]

Gregory Stanton, the renowned American genocide scholar and former U.S. State Department official, who heads the Genocide Watch, has gone so far as to say Myanmar is committing the crime of all crimes, namely a genocide. Stanton states that he is avoiding purposefully the journalistic “ethnic cleansing.” For he views rightly the now popular terminology as Milosevic’s “euphemism,” which is not considered punishable crime in international law.[4]

Ethnic cleansing is a deplorable act committed by a U.N. Member State and its collaborating non-state actors in society, involving violent expulsion of a target population with their distinct ethnic and racial identity from a particular geographic region within the nation’s national boundaries.[5] Burma’s latest round (each marked by its distinctive methods of expulsion and justificatory ideologies) in what has become a decades-old pattern or cycle of targeted violence and destruction against Rohingyas, is typically accompanied by their displacement and flight from the country.

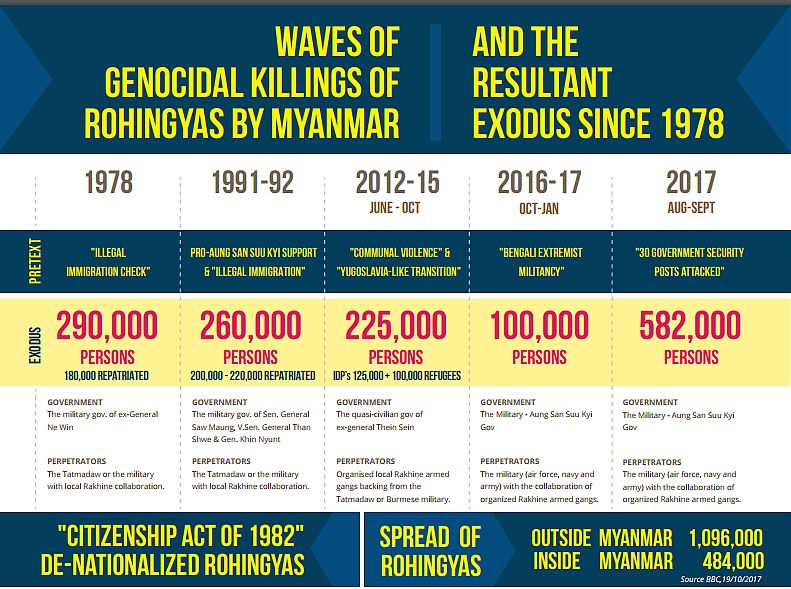

This essay aims to highlight the scope and rhythmic nature of Burma’s persecution of Rohingyas the devastating impact on the Rohingya population. First, it sets out to describe and help readers understand the evolving pretexts given by the successive Burmese governments and the methods of group destruction and resultant waves — five in total — of the outflow of Rohingyas in large number. Then it attempts to offer an interpretive framework within which this cycle of violence-exodus-lull is best understood.

Burma’s Cycles of Terror-Expulsion-Destruction-Exodus-and-Lull

The diagram above captures both the periodic and cyclical pattern of cross-border forced migration of Rohingyas and the biblical volumes of fleeing refugees across Bangladesh-Burmese borders over the last almost four decades.

This pattern of slaughter, structures of severe repression, intervals of lull becomes cyclical since the military-controlled state developed the threat perception regarding the Rohingya population as demographic force of Islamic faith that pose a twofold threat to the country’s predominantly Buddhist character and as a proxy for terrorist groups such as ISIS.[6]

Two striking features of the diagram are the fixed and instrumental role of the Burmese military as the most powerful perpetrator and the shifting nature of the pretexts on which the operations of violent expulsion (which force large numbers of Rohingyas to flee their homes on the Burmese soil) have been based.

In the first large-scale “terror,” as the then Hong Kong-based Fast Eastern Economic Review (July 14, 1978) put it,[7] the campaign that was centrally organized and carried out by the military government of ex-General Ne Win resulted in the exodus of over 280,000 Rohingyas into Bangladesh.[8] Then as now, such large volumes of terror-fleeing Rohingyas forced their way into the neighbouring Muslim country within a short period of about eight weeks. The ostensible pretext of this campaign named “King Dragon Operation” was the “illegal immigration check” of Chittagongnians, that is, Muslim residents of Bangladesh’s Chittagong region that had illegally crossed the 170-miles-long, porous Burmese-Bangladeshi borders and settled in Western Burmese state of Rakhine.[9]

Amid the strong protests and the veiled threat of arming Rohingya refugees by the then military government of Brigadier Zia Rahman in Dhaka, the exodus ended[10] and the Myanmar side agreed to the U.N.H.C.R.-facilitated repatriation. Rangoon took back 180,000-190,000 of the total estimated number of refugees in the same year[11] while many other Rohingya refugees found their way to Pakistan and Saudi Arabia.[12]

The Lull and the Emergence of the Structures of Apartheid

This first exodus was followed by 12-year lull.

More ominously for the Rohingyas, within four years after the violent crackdown on “Illegal immigration” on their ancestral land of Northern Rakhine, they were de-nationalized, that is, Myanmar’s military rulers, under the civilian façade of the Burma Socialist Programme Party, effectively declared them non-nationals who did not belong to Myanmar.

Specifically, in a clever stroke of law enacted in effect as the decree, but rubber-stamped by the People’s Parliament, a paper-tiger, Rohingyas found themselves Myanmar’s Jews. Where violence failed to expel them en masse, Burma’s generals and ex-generals found the blunt instrument in law reminiscent of Nazi-era Nuremberg race laws which disenfranchised and reclassified German Jews as “non-nationals” of the Third Reich. While the Citizenship Act of 1982 never spelled out Rohingyas as their main target one of the two Rakhine members of the drafting committee,[13] the late nationalist historian Dr. Aye Kyaw, made it unequivocally clear, the law was primarily intended to exclude Rohingyas from citizenship eligibility by requiring the non-existent documentation to prove their residency before the first Anglo-Burmese War of 1824.[14] The first-ever printing press imported by the Christian missionaries, arrived in British Burma only in 1870’s. During the pre-colonial (pre-1824), the feudal Burmese society relied on dried palm-leaf as the medium of written language. The idea of documenting one’s residency was un-heard of.

In addition to Burma’s use of this tailor-made citizenship law, it was during this decade of lull, the military set up structures of repression[15] complete with severe restrictions on Rohingyas’ physical movement, deprivation of property rights, establishment of the regimes of forced labour, extortion, control of population growth via stringent marriage restrictions, summary execution and sexual violence.[16]

1991-92 Wave: The Resumption of State-directed Violence after 1988 Nationwide Uprisings

In the six-year period following the passage of 1982 Citizenship Act, increasingly pauperized Burma at large gradually plunged into a period of popular unrest, which culminated in a nationwide peaceful revolt in August 1988, calling for the end of the one-party military dictatorship led by Ne Win and the restoration of democracy and freedom for all.

Like the rest of the country's ethnic groups and social classes, Rohingyas organized mass protests in Northern Rakhine, and rallied behind Aung San Suu Kyi and her newly-founded National League for Democracy (NLD) party, which emerged as the flagship opposition. The fact that this unwanted Rohingya population, which had been legally deprived of the right to belong in Myanmar, attempted to join hands with the emerging opposition movement throughout the country became another impetus for the next round of violent assault on them by the military.[17]

After the military restored “law and order” in the seat of the government in Rangoon and other major urban centers throughout Burma, they turned their attention to the growing popular support among Rohingyas for Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy.

Burmese (military) authorities began confiscating National Registration Cards (NRC) issued before 1982 Citizenship Act was decreed by the head of the military junta ex-General Ne Win: this was a key document which proved Rohingyas to be full-citizens of Myanmar. Instead, the authorities replaced the old NRC cards with “residency cards” (or White Cards, so-called) and began to identify them as “Bengali.” This was designed to drive home the message that they were foreigners who did not belong in Myanmar. While Rohingyas with prior citizenship instantly lost their citizenship status, those who were under 12 years old — the age at which a national becomes eligible for applying for the official national ID cards under Burmese citizenship and immigration law — and the new born are not issued any proof of citizenship. As a matter of fact, Burma in effect render “illegal” thousands of Rohingya babies who were conceived in the wombs of mothers who could not afford exorbitant fees to secure marriage licenses and secretly wedded in the presence of Muslim spiritual leaders.[18]

Prior to her first house arrest in July 1989, Aung San Suu Kyi herself travelled to Northern Rakhine and patronized local NLD chapters in the predominantly Rohingya areas.

On their part, Rohingyas saw new rays of hope in the burgeoning opposition movement with Suu Kyi as the most popular, if untested leader.[19] In 1992, Myanmar military intelligence established an inter-agency military unit named “Border Affairs Division” (or Na Sa Ka), which was then used as the main instrument to crush the pro-democracy Rohingya communities. The angry sentiment — how dare “the Bengali illegals” offered their solidarity to the Burmese generals’ nemesis — appears to have added a new layer of sadism to the rationale behind the systematic persecution of Rohingyas.[20]

In no time, the Na Sa Ka in effect turned Northern Rakhine’s Rohingya villages, wards and towns into a vast web of security grids dotted with armed check-points. The troops began to commit a laundry list of major human rights violations including forced labour, severe restrictions on physical movements, extortions, summary executions, sexual violence, marriage and child birth restriction, confiscation of previously issued national identity cards. This new wave of repression by the central military triggered the second exodus of Rohingyas in 1992. According to the U.N.’s count, “a total of 256,193 Rohingyas fled of which 236,393 were repatriated while nearly 20,000 were too afraid to return to N. Rakhine and stayed on.”[21]

As a matter of fact, the second wave of exodus and the growing repression against Rohingyas caught the attention of the United Nations in New York and pro-Aung San Suu Kyi human rights campaigners. It became one of the major factors — the other were civil war-related rights violations in Eastern Burma in the regions of Karens, Shan, Karenni and the general repression against the NLD opposition, with the freshly minted Nobel Peace Prize winner under her first house arrest — leading to the appointment of the Special Rapporteur on human rights situation in Myanmar beginning in 1992.[22]

A pattern of exodus-repatriation-lull began to emerge.

It was during this period of lull that Rohingyas came to be subjected to the emerging genocidal conditions, which included severe restrictions of access to essential life-sustaining services such as emergency medical care, preventative medicine, enough nutrition, unnatural control over birth via severe restrictions on marriage licenses, and so on. While the national average for physican: patient ratio is 1:691, in the combined two main Rohingya towns of Maung Daw and Buthidaung, Rohingyas: doctor ratio is 158,000: 1, according to the Harvard Medical School research team which studied the public health situation of Rohingyas.[23] The direct outcome of the policy-induced health and food deprivation is felt most acutely among Rohingya children, as pointed out earlier.

As early 2006, these structures of repression and the resultant genocidal conditions, that is, conditions that have in effect made life for the Rohingya population nearly impossible, were noted in the dispatch, marked “Confidential” and dated February 20, 2006, sent by M. Kairuzzman. Bangladesh’s ambassador in Rangoon, to the Foreign Secretary in Dhaka. After the site visit under the U.N.H.C.R. auspices to Northern Rakhine with its 97 percent make-up of Rohingyas, Ambassador Kairuzzman wrote:

according to the UNHCR statistics, the government (of Burma) has engaged a platoon of Na Sa Ka/Army personnel (retired/serving) for 100 (Rohingya) people who enforce curfew at night whenever they feel only for the Muslims … For 104 hamlets/villages in N. Rakhine state, there are 58 check-posts to harass the Muslim population out of which 80% are illiterate, 65% of children are suffering from malnutrition, and mortality rates are 4 times higher than other parts of Myanmar. Northern Rakhine state’s glittering pagodas in every nook and corner are only for the 3% of the Buddhists. On the contrary, only a handful of mosques seen on the roadsides are in such dilapidated conditions that itself bar Rohingyas from going to mosques. In most places, Muslims are not allowed to pray inside the mosques. Northern Rakhine state are highly infested with T/B, malaria and diarrhea …. These days the government provides them a document called “Residence Document” for those who can fulfil these conditions: 1) speak in Myanmar language; 2) marriage certification; and 3) birth certificate.[24]

Eleven years on, these man-made conditions have remained in place.

As recently as July 2017 the World Food Program found that up to 80,500 Rohingya children under the age of five are suffering from “acute malnutrition,”[25] that is, euphemism for sub-Sahara like semi-famine. WFP conducted Food assessment among the Rohingya population between December 2016 and March 2017, the WFP released its preliminary findings. It reports, “based on the household hunger scale, about 38,000 households corresponding to 225,800 people are suffering from hunger and are in need of humanitarian assistance.”[26] Further, the WFP report states, “high food insecurity, limited access to essential services including health care, and poor ac-cess to safe water and sanitation may have exacerbated an already serious malnutrition situation (based on DHS 2015-16 for Rakhine State, the Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM) was at 13.9 percent while the Severe Acute malnutrition (SAM) - 3.7 percent). None of the children from 6 to 23 months met the minimum adequate diet, only 2.5 percent reached minimum dietary diversity and 8.5 percent met the minimum meal frequency.”[27]

These inhuman conditions and structures of direct repression by Myanmar security troops have also been a major factor behind wave-like streams of Rohingyas fleeing Myanmar.

After the ten-year lull since the second cycle which ended with the second repatriation of Rohingyas in 1994-95, the communal riots broke out in several towns in Rakhine state in June and October of 2012.

The Communal or Sectarian Violence of June and October 2012

It is noteworthy that on the eve of the communal riots in June, there were two significant developments, which caused, without a doubt, concerns among the military leaders.

First, Aung San Suu Kyi decided to play electoral politics, even within the structural constraints of 2008 Constitution drawn up by the military with the sole aim of ensuring its unchallengeable position in national politics. In April 2012, her party contested for all the available seats in the by-elections, and her NLD contestants defeated every single one of their military-backed opponents.[28]

Second, because of the media and political freedoms ushered in by the government of ex-General President Thein Sein Rakhine nationalists were emboldened to make loud and public demands for greater political and administrative autonomy for Rakhine people from the central government in Naypyidaw and the equitable sharing of revenues originated from one of the country’s biggest income earners — offshore natural gas sales, all of which hitherto went into the military’s coffers.[29]

No sooner had Aung San Suu Ky’s party swept the parliamentary by-elections in April 2012 than the story of three “Bengali” Muslims gang-raping and murdering a 28-year-old Rakhine Buddhist woman in a town called Taung Goke. While the murder indeed took place in May, the rape story was completely false, according to Zargana, a well-known political comedian and former dissident, who served as one of the members the Presidential Commission on Rakhine Violence formed in the wake of the communal violence.[30] He interviewed the government’s coroner who performed the post mortem on the victim, but who was forced to state otherwise in his medical report. And Myanmar’s official media outlets — and Thein Sein’s presidential spokesperson — spread the false story of “Muslim Bengali men” gang raping a Buddhist Rakhine. In retaliation, a well-organized mob in Taung Goke town dragged ten Burmese Muslim leaders from their inter-state bus travelling back to Rangoon from their pilgrimage in Rakhine sate and slaughtered them on the street in broad daylight, and in full view of the local police and military.[31] That set off communal riots across half a dozen towns across Rakhine. The violence broke out again in October the same year, this time with the participation of the government military and police units, on the side of the Rakhine Buddhists.[32]

Unlike the first two waves of exodus which were triggered by the military-directed terror and repression, the bouts of violence in 2012 took on the “communal” characteristic, with the “reformist” government giving organized anti-Rohingya Rakhine mobs a blanket impunity as they killed Rohingyas and destroyed Rohingya neighborhoods, places of worship, and businesses. In some cases the security forces joined in the orgy of violence and destruction of Rohingyas.[33]

Myanmar’s official narrative about the violence and exodus has again shifted from one of “illegal immigration” to “communal violence” between the two mutually hostile local Buddhist and Muslim communities, with a long history of violent clashes dating back to the World War II era.

The international media and influential think tanks such as the Brussels-based International Crisis Group (ICG)[34] began echoing this new official narrative in which the instrumental role of local Myanmar security forces, that simply told the Rohingya victims who begged for protection from organized mob attacks to simply “pray to your Allah,”[35] and the central government that provided the impunity to anyone who inflicted death and destruction on Rohingyas. While portrayed as “sectarian or communal violence,” Rohingya people bore the overwhelming destruction and death — 86 percent, as estimated by the Kofi Annan-led Rakhine Commission Report, released in September 2017.[36]

Overlooking the previous waves of state-organized violence and repression of 1978 and 1991-92, influential external players such as ICG, U.N. agencies, the E.U. and various foreign governments began to promote a new “democratic transition” narrative that the “sectarian violence” in Rakhine was an unfortunate but almost inevitable part of a transitional process during which multi-ethnic societies undergo liberalization. But this narrative of the overwhelming violence against Rohingyas is contradicted by the policy-induced cycle of violence-exodus-lull, which dates to the time during which the country was completely closed off from the outside world and ruled tightly by the military junta with no signs of political or economic liberalization.

The Fourth and Fifth Cycles of Violence and Exodus: “Muslim Terrorism”

In the last two waves of violence and exodus in 2016 and 2017, Myanmar government and Burmese language private media outlets began peddling yet another pretext for the use of central’s government troops, namely Myanmar’s national defence against the emerging ISIS-inspired “Bengali extremist terrorists”.[37] The primitively armed Rohingya militant group named Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) did launch two clusters of attacks against Myanmar’s armed security outposts, typically with sticks, spears, swords and a “handful of home-made grenades and guns,” in October 2016 and August 2017.[38]

In both attacks the militant reportedly killed a total of two dozen police. As a matter of fact, the attacks by the primitively armed Rohingya young men only handed Myanmar government a “pretext” to launch another large scale assault on the Rohingya people, as former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM) Eric Schwartz told PBS News Hour on October 13, 2017.[39]

In fact, following the two bouts of “communal violence” in Rakhine Myanmar government had been trying to unsuccessfully to re-frame the issue of Rohingyas as a national security concern, namely that of “Jihadist terrorism.” No one other than ex-Major Zaw Htay, the current spokesperson for Aung San Suu Kyi government with the ranks of Director General in the President’s Office, was openly promoting the verifiably false rumors that “fully armed Bengali terrorists had crossed the Burmese borders to commit terrorist attacks on Burmese soil” if they were “army intelligence field reports.[40] At the time Zaw Htay was one of two presidential spokespersons for the ex-General and President Thein Sein. His fear-mongering about “Bengali terrorism” predated at least three years before the emergence of Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army. Despite Myanmar’s sustained efforts to reframe persecution and violent repression of the Rohingya people as “national defence against Islamic terrorism,”[41] not even the United States Government, which has been at the forefront of “the global war on terror,” has bought Myanmar’s new and unconvincing narrative.

However, this narrative has been very well-received by the public in Burma, as well as Aung San Suu Kyi herself. Through this “Myanmar war on Muslim terror” narrative, the Burmese military has not only burned down thousands of Rohingya homes in nearly 300 villages in the region of N. Rakhine stretching over 100 kms. in length but it has destroyed the predominantly Buddhist society’s demands for human rights for all, greater freedom and further democratization.

Conclusion

Today, there are more Rohingyas outside of their ancestral borderlands of Myanmar and Bangaldesh than inside. The exact death toll of Rohingyas, both men and women, children and elderly, will never be known. For the loss of two dozen police, Myanmar has inflicted overwhelming and pre-planned violence and terror against the virtually helpless and unarmed population. In the virtual world of Burmese language Facebook individual Burmese soldiers have boasted that they have slaughtered a large number of Rohingyas while Bangladeshi authorities estimate the death toll to be several thousands.

On October 27, 2017, the three-member U.N. Fact Finding Mission issued a brief official statement upon completion of their week-long visit to Bangaldesh where they interviewed scores of Rohingya refugee out of a total of 600,000 new arrivals. In the words of the mission’s leader former Indonesian Attorney General Marzuki Darusman, “We have heard many accounts from people from many different villages across northern Rakhine state. They point to a consistent, methodical pattern of actions resulting in gross human rights violations affecting hundreds of thousands of people.” Mazzuki was also quoted as saying the number of Rohingya killed (in the most recent wave of Burmese state-directed violence) may be “extremely high.”

This Mission’s one-page statement came on the heel of a damning field report (September 13-24, 2017) by the U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (O.H.C.H.R.), which states:

Credible information indicates that the Myanmar security forces purposely destroyed the property of the Rohingyas, scorched their dwellings and entire villages in northern Rakhine State, not only to drive the population out in droves but also to prevent the fleeing Rohingya victims from returning to their homes. The destruction by the Tatmadaw of houses, fields, food-stocks, crops, livestock and even trees, render the possibility of the Rohingya returning to normal lives and livelihoods in the future in northern Rakhine almost impossible. It also indicates an effort to effectively erase all signs of memorable landmarks in the geography of the Rohingya landscape and memory in such a way that a return to their lands would yield nothing but a desolate and unrecognizable terrain. Information received also indicates that the Myanmar security forces targeted teachers, the cultural and religious leadership, and other people of influence in the Rohingya community in an effort to diminish Rohingya history, culture and knowledge.[42]

This report also highlights that prior to the incidents and crackdown of August 25, a strategy was pursued to: 1) Arrest and arbitrarily detain male Rohingyas between the ages of 15-40 years; 2) Arrest and arbitrarily detain Rohingya opinion-makers, leaders and cultural and religious personalities; 3) Initiate acts to deprive Rohingya villagers of access to food, livelihoods and other means of conducting daily activities and life; 4) Commit repeated acts of humiliation and violence prior to, during and after August 25, to drive out Rohingya villagers en masse through incitement to hatred, violence and killings, including by declaring the Rohingyas as Bengalis and illegal settlers in Myanmar; 5) Instil deep and widespread fear and trauma — physical, emotional and psychological — in the Rohingya victims via acts of brutality, namely killings, disappearances, torture, and rape and other forms of sexual violence.[43]

Whatever one may choose to call name of Myanmar’s persecution of Rohingyas, “genocide,”“crimes against humanity,” “ethnic cleansing,”one thing is beyond dispute: Burma’s military and local Rakhine non-state collaborators have been engaged in the cycle of violence-expulsion-destruction-exodus-lull of biblical volumes over the last 39 years since the first large-scale centrally-organized campaign of terror against Rohingyas. Only Burma’s official pretexts and the methods of destruction have evolved, but the devastating impact on both the lives of individual Rohingyas and the existence of Rohingyas as a distinct ethnic community remains constant.

International lawyers, U.N. officials and world leaders may and do debate as to whether Myanmar’s mass atrocities constitute the crime of all crimes, a genocide. But over one million Rohingya refugees, displaced in Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Malaysia, India and other countries and the smaller number that are being trapped inside Northern Rakhine State between the unwelcoming world and the hateful Burmese society do not have the luxury of deciding what to call the crimes they have been subjected to for nearly 40 years.

Alas, as the diagrammatic waves of terror-exodus show, the mythical international community has once again made a mockery of the rally cry against genocides “Never again!”

[1] “Myanmar Army Conducts Clearance Operations; Thousands Flee Clashes,” Voice of America, August 28, 2017, accessed November 12, 2017, https://www.voanews.com/a/myanmar-army-conducts-clearance-operations-in-rakhine-state/4003642.html. Also see Global Center for the Responsibility to Protext, “Populations at Risk Current Crisis,” October 15, 2017, accessed November 12, 2017 http://www.globalr2p.org/regions/myanmar_burma.

[2] “Myanmar Refugee Exodus Tops 500,000 as More Rohingya Flee”, US News & World Report, September 27, 2017, accessed November 11, 2017 https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2017-09-29/myanmar-refugee-exodus-tops-500-000-as-more-rohingya-flee.

[3] “UN human rights chief points to ‘textbook example of ethnic cleansing’ in Myanmar,” UN News Center, September 11, 2017, accessed November 12, 2017 http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=57490#.Wgg3AMZl-mY. See also “UN Chief Assails 'Ethnic Cleansing’ of Myanmar's Rohingyas,” Voice of America, September 13, 2017, accessed November 12, 2017 https://www.voanews.com/a/united-nations-antonio-guterres-myanmar-rohingya-ehtnic-cleansing/4027395.html.

[4] “Expert Witness Dr. Gregory Stanton’s Statement,” Delivered at the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal on Myanmar, Faculty of Law, University of Malaya Kuala Lumpur, September 18, 2017, accessed November 12, 2017, https://tribunalonmyanmar.org/2017/09/18/expert-witness-dr-gregory-stantons-statement/.

[5] For literary definition of ethnic cleansing see “ethnic cleansing,” Oxford English Living Dictionaries, accessed November 12, 2017, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/ethnic_cleansing.

[6] For the Burmese military’s institutionalized view of Rohingya Muslims as a threat see (ex-Colonel) Ye Htut, “A Background to the Security Crisis in Northern Rakhine,” ISEAS Perspective 2017/79, accessed November 12, 2017, https://www.iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/ISEAS_Perspective_2017_79.pdf. (Hereafter “A Background to the Security Crisis in Northern Rakhine”). In contrast, a British researcher Joseph Allchin offers a different perspective. See Joseph Allchin, "Myanmar: The Invention of Rohingya Extremists,” The New York Review of Books, October 2, 2017, accessed November 12, 2017 http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2017/10/02/myanmar-the-invention-of-rohing….

[7] William Matten, “Burma’s Brand of Apartheid,” Far Eastern Economic Review, July 14, 1978.

[8] For the details of this state-directed first large scale anti-Rohingya campaign see ex-General Khin Nyunt, The State’s Western Gate Problem (in Burmese, hereafter cited as “The State’s Western Gate Problem”) (Yangon: One Hundred Flowers Press, 2016) 21-60.

[9] Ibid. pp. 21, 22, & 23.

[10] Interview with F. K. Jilani (deceased), a prominent Rohingya teacher and community leader, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, May 2013.

[11] “The State’s Western Gate Problem”, p.p.29-31.

[12] Interviews conducted face-to-face in 2014 and 2015 with Rohingya activists in Germany and the U.K. who initially went to Pakistan and Saudi Arabia after their temporary refuge in Bangladesh.

[13] For a legal analysis of the Citizenship Act, see Benjamin Zawacki, “Defining Myanmar’s “Rohingya Problem””, American University Washington College of Law's Human Rights Brief 20, 3 (Spring 2013).

[14] The late Aye Kyaw was a Monash University-trained Rakhine historian, who served on the Citizenship Drafting Committee established by ex-General Ne Win, the then despot. In his Burmese language interview five years ago to Irrawaddy News Magazine, Aye Kyaw emphatically stated that the new Citizenship Act was aimed specifically at de-nationalizing and disenfranchising Rohingyas, whom he considered the British colonial-era agricultural “coolies” from Chittagong, East Bengal. The Irrawaddy News Group has emerged as the leading cheerleader justifying persecution of Rohingyas, and has since removed Aye Kyaw-incriminating Burmese language from its website.

[15] See “A Background to the Security Crisis in Northern Rakhine,” 4.

[16] UN Commission on Human Rights, Situation of human rights in Myanmar, March 3, 1992, E/CN.4/RES/1992/58, accessed November 12, 2017, http://www.refworld.org/docid/3b00f02154.htm. Also see Human Rights Watch, “Burmese Refugees in Bangladesh: Still No Durable Solution,“ May 1, 2000, accessed November 12, 2017, http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6a86f0.html.

[17] Interview with Ro Nay San Lwin, a well-respected Rohingya activist based in Germany, whose uncle led the local efforts in N. Rakhine state to mobilize Rohingya community support for Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy, 2015.

[18] Interview with Rohingya Blogger U Ba Sein, London, U.K., 2016.

[19] See AFK Jilani, “Aung San Suu Kyi: The Lady of Destiny,” The Taj Library Press, Chittagong, Bangladesh. The late Jilani was a Rohingya educator and writer who resettled in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

[20] Interview with Ro Nay San Lwin, 2015.

[21] Dispatch No. 102, marked “Confidential” and addressed to Bangladesh Foreign Secretary (February 20, 2006), from Bangladesh Ambassador to Yangon, Myanmar. (Hereafter “Dispatch 102”), accessed November 12, 2017, http://www.maungzarni.net/2017/10/myanmars-ethnic-cleansing-of-rohingyas.html.

[22] “Situation in Myanmar,” U.N. General Assembly resolution A/RES/47/144, adopted on December 18, 1992, accessed November 12, 2017, http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/47/a47r144.htm.

[23] Syed S. Mahmood et al., “The Rohingya people of Myanmar: health, human rights and identity,” The Lancet 288, December 1, 2016. See The Lancet Editorial on the review article here, accessed November 12, 2017, http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(16)32458-8/fulltext.

[24] “Dispatch 102”.

[25] “Food Security Assessment of the Northern Part of Rakhine State,” World Food Program (WFP), July 2017. “Hunger rife among Rohingya children after Myanmar crackdown: WFP,” Reuters, July 5, 2017 (Hereafter “Food Security Assessment”), accessed November 12, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-rohingya-malnutrition/hunger-rife-among-rohingya-children-after-myanmar-crackdown-wfp-idUSKBN19Q1WC. Subsequently, the U.N. agency withdrew this report after its official release as the direct result of the objection by Myanmar Government of Aung San Suu Kyi. See Oliver Holmes, “UN report on Rohingya hunger is shelved at Myanmar's request,” The Guardian, October 17, 2017, accessed November 12, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/17/un-report-on-rohingya-hunger-is-shelved-at-myanmars-request.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] “Burma's Aung San Suu Kyi wins by-election: NLD party,” BBC, April 1, 2012, accessed November 12, 2017, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-17577620.

[29] Shwe Gas Movement’s statements and press releases – shown on its website up to 2012 – exemplify this grassroots demand from Rakhine community for more equitable revenue sharing and opposition to the Burmese military’s increased presence in Rakhine State, accessed November 12, 2017, http://www.shwe.org/press-releases/.

[30] Personal telephone and face-to-face communications with the Burmese author. 2012. Also see Maung Zarni, “Did the gov’t incite the racial violence targeting the Rohingya?” Democratic Voice of Burma, October 2, 2017, accessed November 12, 2017, http://www.dvb.no/analysis/did-the-govt-incite-the-racial-violence-targeting-the-rohingya/24116.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Human Rights Watch, “All You Can Do is Pray.”

Crimes Against Humanity and Ethnic Cleansing of Rohingya Muslims in Burma’s Arakan State (Hereafter “All you can do is pray”), April 22, 2013, accessed November 12, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/report/2013/04/22/all-you-can-do-pray/crimes-against-humanity-and-ethnic-cleansing-rohingya-muslims.

[33] Ibid. Summary.

[34] Jim Della-Giacoma, “A Dangerous Resurgence of Communal Violence in Myanmar,” ICG, March 28, 2013, accessed November 12, 2017, https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/dangerous-resurgence-communal-violence-myanmar.

[35] “All You Can Do is Pray.”

[36] “Towards a Peaceful, Fair and Prosperous Future for the People of Rakhine,”

Final Report of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, August 23, 2017, accessed November 12, 2017. http://www.rakhinecommission.org/the-final-report/

[37] Maung Zarni, “Is Irrawaddy News Group leading Myanmar genocide propaganda?” August 6, 2017, accessed November 12, 2017, http://www.maungzarni.net/2017/08/is-irrawaddy-news-group-leading.html. Also see “Rohingya: Hate speech, lies and media misinformation,” Al Jazeera English Listening Post, September 16, 2017, accessed November 12, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/listeningpost/2017/09/rohingya-hate-speech-lies-media-misinformation-170916072755690.html.

[38] “Myanmar: Who are the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army?” BBC, September 6, 2017, accessed November 12, 2017, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-41160679.

[39] “What can stop the extreme violence against Rohingya Muslims?” PBS NewsHour, October 13, 2017, accessed November 12, 2017, https://svit.vkadri.com/video/pbs-newshour-what-can-stop-the-extreme-violence-against-rohingya-muslims.html.

[40] On file with the authors is the screenshot of a Facebook Timeline on the then President Thein Sein’s spokesperson ex-Major Zaw Htay, June 2013. He is now Aung San Suu Kyi Government’s spokesperson.

[41] “A Background to the Security Crisis in Northern Rakhine.”

[42] See U.N. Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights, “Mission report of OHCHR rapid response mission to Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh,” September 13-24, 2017, accessed November 12, 2017, http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/MM/CXBMissionSummaryFindingsOc….

[43] U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Mission report of OHCHR rapid response mission to Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 13-24 September 2017,” October 11, 2017. Accessed November 12, 2017. https://reliefweb.int/report/myanmar/mission-report-ohchr-rapid-response-mission-cox-s-bazar-bangladesh-13-24-september.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.