Introduction

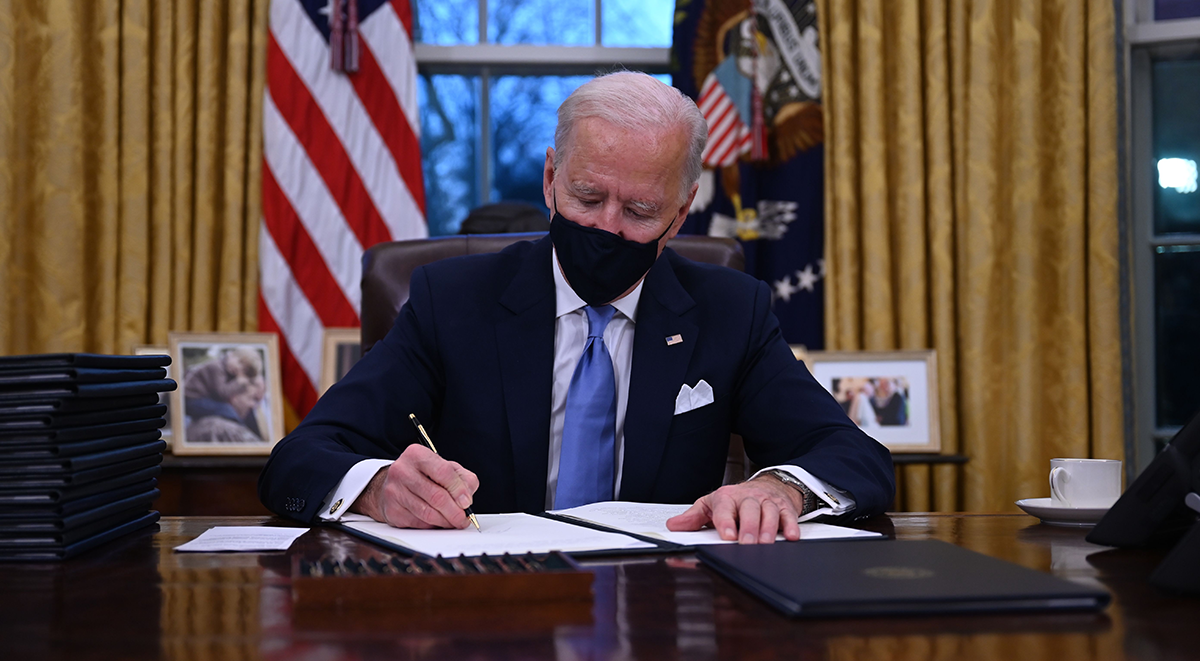

As the Biden administration takes office, it faces a host of challenges, both at home and abroad. Where does the Middle East fit into all of this and what should the new administration prioritize in its first 200 days? In the second part of a two-part series, we asked experts and scholars from across the region to weigh in with their thoughts.

Read part one: The view from Washington

This publication is part of MEI's series on the Biden Transition.

Viewpoints

-

Karim Haggag

Karim Haggag

Early attention to the region’s latent crises

The foreign policy team of the Biden administration has signaled a scaled-down approach when it comes to the Middle East. Grand ambitions of reshaping the regional order through regime change, military intervention, and settling the region’s myriad conflicts have given way to a more modest — but still challenging — agenda of containing Iran’s nuclear program, ensuring a modicum of stability to enable the downsizing of the U.S. military presence in the region, and extricating the U.S. from indirect involvement in Saudi Arabia’s intervention in the Yemen war.

This aligns with a trend toward recalibrating American interests in the region, focusing primarily on containing the twin threats of weapons of mass destruction and counter-terrorism.

However, while this agenda might preoccupy the administration during its first year in office, it also needs to devote early attention to a series of “latent crises” that implicate America’s regional interests, even when those interest are defined in minimal terms.

The eastern Mediterranean is stark example. Driven primarily by Turkey’s coercive approach toward the region’s natural gas discoveries and maritime border disputes, this increasingly militarized geopolitical competition has involved Egypt, Israel, Greece, and France, producing a regional flashpoint akin to the situation in the South China Sea. Early attention by Washington can halt further escalation by active diplomacy to mediate disputes over maritime boundaries, coupled with strong opposition to the use of coercive diplomacy by all states, and a road map for regional cooperation to exploit the region’s hydrocarbons resources.

The intensified competition between America’s allies has also become linked to a growing trend of military intervention in the region’s conflicts, especially Libya and Syria. Turkey has tied its intervention in the Libyan civil war to its claims in the eastern Mediterranean, prompting Egypt to enunciate a “red line” against further Turkish advancement toward its borders. In Syria, Turkey has become entangled in the north against the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD), while Israel is waging a concerted military campaign to preempt Iran from consolidating its military presence in the south. A proactive engagement on the part of the Biden administration should aim to ensure that regional intervention in both conflicts does not complicate the search for a political settlement, or produce the conditions for the reemergence of terrorist safe havens. Concerted U.S. diplomacy can give much-needed momentum to the ongoing U.N.-supported conflict resolution efforts that have gained some traction in both Libya and Syria.

The dispute between Egypt and Ethiopia over the latter’s construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile constitutes yet another latent crisis facing the administration. Given Egypt’s reliance on the Nile waters for 95% of its water supply, the impasse in the negotiations threatens to escalate to the point of open conflict. Here too the Biden administration can intervene early to defuse a potential crisis by reviving the mediation effort undertaken by its predecessor on the basis of the agreement brokered by the Trump administration, which Ethiopia refused to sign.

Finally, deferring engagement on the Israeli-Palestinian front until conditions are “ripe” threatens to accelerate the transformation of the conflict to a one-state reality, a situation that could rapidly degenerate into another round of violence. Rushing to launch yet another iteration of the peace process before careful preparation should be avoided. But the administration should at least signal its repudiation of Donald Trump’s “Deal of the Century” and reiterate America’s commitment to the tenets of the two-state solution as the basis for a settlement: a Palestinian state based on the 1967 borders, Jerusalem as the capital of two states, and a just settlement for Palestinian refugees.

Karim Haggag is a professor of practice in the School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the American University in Cairo and a visiting fellow at the Middle East Initiative at the Harvard Kennedy School.

-

Lina Raafat

Lina Raafat

US counterterrorism efforts must be anchored in long-term prevention and resilience building

While the Biden administration has vowed to prioritize ending “forever wars” and great power competition with China and Russia over counterterrorism, it will soon be forced to grapple with an incredibly complex and multifaceted terrorist threat — perhaps much sooner than it had hoped to.

Despite the demise of its physical caliphate in Iraq and Syria, ISIS remains a potent threat. It continues to operate as an insurgency in both countries and the root causes that drove its establishment have not been addressed. ISIS’s territorial defeat forced the group to look outwards, effectively expanding its geographic reach and rebranding itself as a global jihadist movement. The security implications of this could be catastrophic.

Particularly alarming is ISIS’s expansion in West Africa, where the group has rapidly fortified its presence through regional affiliates. A combination of weak institutions, limited state capacity, widespread poverty, and ethnic tensions render the region increasingly susceptible to terrorist encroachment. In a region with immense untapped resources, limited state presence, and a growing disenfranchised young population susceptible to recruitment, citizens’ faith in their governments is eroded, encouraging them to seek alternative — and oftentimes radical — ideologies.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated and magnified these pre-existing threats, compounding structural weaknesses and pockets of fragility, and inadvertently provided terrorist groups with an unparalleled opportunity to expand their territorial footprint, augment recruitment, and position themselves as alternative service providers vis-à-vis the state.

While the Biden administration’s “counterterrorism plus strategy” increases reliance on allied local partners, it must be underscored that security-based counterterrorism responses, though necessary, are by no means sufficient to effectively deal with the multifaceted nature of the threat that presents itself today. U.S. counterterrorism measures must be complemented by a preventative approach based on good governance and inclusive sustainable development that addresses the structural drivers of extremism and terrorism. Preventative efforts at the local level need to focus on strengthening community cohesion and rebuilding the frayed social contract.

Joe Biden’s objective of ending “forever wars” cannot be achieved without serious investment in a preventative approach and empowerment of local partners. This should not be constrained to local allied forces, but should also extend to civil society actors and communities at-large.

While the aforementioned shift to a prevention paradigm requires long-term commitment, short-term, low-cost steps can be taken by the administration immediately. These include reinstating development assistance and humanitarian aid and relief, which are of the utmost importance in light of COVID-19. Furthermore, and due to the increasingly localized nature of terrorism, it is now more important than ever to foster partnerships with local actors that go beyond a mere focus on counterinsurgency. The Biden administration should increase support to civil society actors, as local communities represent the first line of defense in the face of violent extremism. Investing in a prevention paradigm alongside counterterrorism efforts ensures that U.S. strategic interests are protected in the long term.

Lina Raafat is a non-resident scholar with MEI’s Countering Terrorism and Extremism Program and works at the Cairo International Center for Conflict Resolution, Peacekeeping, and Peacebuilding.

-

Abdulkhaleq Abdulla

Abdulkhaleq Abdulla

The US needs to do more in the Middle East, not less

Given the variety of urgent American domestic priorities as well as the dozens of critical global issues, it is safe to assume that the decades-old problems of the Middle East will not figure high on President Joe Biden’s list of top policy interests in his first 200 days in office.

Indeed, we have already heard this from Antony Blinken, President-elect Biden’s choice to lead the State Department, who at a Hudson Institute event in July 2020 said that “I think we would be doing less, not more, in the Middle East.”

If Blinken stays true to his word, then we probably will see less of America in the Middle East, not only in the first 200 days, but for the next four years of the Biden presidency.

Blinken’s view of the region is consistent with the prevailing conventional wisdom among pundits in Washington that the U.S. has had enough of the Middle East. It has been viewed negatively, as a political liability and a strategic burden, rather than as a strategic asset, as it used to be seen during most of the Cold War. Even the oil-rich Arab Gulf is no longer considered a vital U.S. interest as it was some 20 years ago. Israel, of course, will remain untouchable as a special case that no American politicians would dare tamper with.

Yet the view that the U.S. will do less, not more, in the Middle East during President Biden’s first 200 days in office and beyond is simplistic and even naive. It is also wishful thinking that many previous American administrations hoped to start their term with, only to find to their surprise that it is easier said than done.

The Middle East has always dragged in American presidents during their time in office, and President Biden will be no exception. This is true for a variety of reasons that are specific to the region.

To begin with, it is full of America’s allies and friends as well as its foes. Some of America’s closest partners and some of its deadliest enemies are all packed into this one region stretching from Pakistan to Morocco, and covering everything in between. They need to be attended to from day one.

Also, the region’s 700 billion barrels of oil reserves might not be a vital interest for America now that it is an oil independent country, but vital interests aside, America still has vast commercial, financial, political, and strategic interests throughout the Middle East. It will be politically costly to contemplate even a minimum of disengagement with the region.

Accordingly, it does not make sense to put the region on hold awaiting a long review and reassessment of policy that typically takes at least six months to complete. That is simply too much of a luxury when it comes to the Middle East, a region that has not lost one iota of its strategic value.

Thus, the Biden administration will most likely stay focused on the critical regional issues in its first 200 days. The most urgent of these issues that needs immediate attention is Iran and its destabilizing behavior. The second is how best to contain Turkey's expansionist appetite. The third issue is to build on the success of the Abraham Accords and strengthen the ties between the UAE and Israel. They need to be promoted as the new two pillars of regional stability. Finally, if the Biden administration is serious about reversing the Trump-era policy of “America first” and delivering on its belief that America is stronger working with its allies, then it will not find better partners to work with than Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and the other Arab Gulf states.

All of this necessitates America pay more, not less, attention to the Middle East. It means we will see more America diplomats sent to the region, not fewer. And more American generals, not fewer. And even more American investments, not fewer.

Abdulkhaleq Abdulla is a professor of political science from the UAE.

-

Rudayna Al-Baalbaky

Rudayna Al-Baalbaky

The new administration’s focus should be on Iran and ISIS

Two of the key priorities for the Biden administration in the Middle East should be to continue limiting Tehran's role and to prevent a potential ISIS resurgence in Iraq and Syria. In the short term, the U.S. could start by acting directly in northeast Syria, where it maintains counterterrorism- and Iran-focused missions, and continue to work primarily through partners on the ground to contain or defeat these two “imminent regional threats.”

Airstrikes are seemingly far from being sufficient to contain Iran. In fact, these have limited, but not prevented, the flow of pro-Iranian militia members and weapons, especially missiles, which are viewed as a primary factor of regional destabilization and as a strategic security threat by traditional U.S. allies. There could be a window of cooperation with Russia, if effective control of the Syrian-Iraqi borders is envisaged. In fact, Russia has recently increased its activity on the border between Syria and Iraq, specifically in al-Bukamal in Deir ez-Zor, where the Russian military has expanded its checkpoints and pro-Russian militias have increased their recruitment, at the expense of Iranian ones.

At the junction of the Euphrates river and al-Khabour river valleys in Deir ez-Zor, ISIS has concurrently increased its attacks against the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), as well as against prominent members of Arab tribes that are cooperating with the SDF and the U.S.-led coalition against ISIS. Since the beginning of the new year, ISIS has expanded its activities to the governorates of al-Hasakeh and Ar-Raqqa. The competition between adversarial powers is mounting and the U.S. approach of fully subcontracting its work to allies on the ground may not be sufficient to prevent further destabilization, humanitarian crises, and displacement in the region. The U.S. needs to commit and leverage its diplomatic power to manage the adversarial relationship between its local partner in the fight against ISIS, the SDF, and Turkey in the short term. The allegations of mismanagement and corruption in SDF-controlled areas — such as the administration of al-Hol camp — are further destabilizing the region, resulting in growing and increasingly vocal support for ISIS and potentially fueling its insurgency.

Rudayna Al-Baalbaky is the coordinator of the International Affairs Program at the American University of Beirut’s Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs.

-

Yoel Guzansky

Yoel Guzansky

Avoiding US-Israel confrontation over Iran

After four years in which Israel enjoyed almost full political backing from the U.S., with "maximum pressure" on Iran and normalization with several Arab countries, Jerusalem should now work to adapt to the Biden administration. It seems that the U.S. will continue to support the normalization processes between Israel and the Arab states, even if it might be less generous with the American "payment" for these arrangements.

However, the major challenge facing bilateral relations will be over Iran. The handling of the Iranian nuclear issue as it pertains to the gap between Jerusalem and Washington could largely define the nature of relations between the two allies in the next four years.

President Joe Biden has stressed that he intends to return to the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, including lifting the sanctions reinstated by the Trump administration, assuming Tehran returns to full compliance with its obligations under the agreement. In contrast, Israel has underscored its opposition to a return to the deal as it stands. In the face of the apparent determination of the new administration to rejoin the agreement, it seems that Jerusalem has chosen a public and confrontational approach.

Continuing down that path will be a mistake. Conducting a public campaign instead of a discreet professional dialogue could escalate into a confrontation that is undesirable for both countries. Another mistake would be not to use the existing leverage created by the Trump administration to continue to pressure Iran to enter into negotiations that will lead to a new and more comprehensive agreement.

While the two countries should agree on the goal — that Iran cannot be allowed to develop a nuclear weapons capability — they differ on the best path toward achieving it. Making those disagreements public, however, could dampen Israel-U.S. relations and might negatively affect Israel's ability to impact the policy being crafted on Iran. For its part, the Biden administration also has an interest in gaining Israel's backing for its Iran policies, both to better deal with the matter and as part of the need to mobilize support in Congress.

Yoel Guzansky is a senior research fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS).

-

Shahla Al-Kli

Shahla Al-Kli

A more stable Iraq will mean a more stable Middle East

Since the 2018 elections, Iraq has been going through a critical transformation, dominated by four major dynamics:

- Nascent positive social and cultural trends, manifesting in a youth movement and public political maturity, that have been successful in galvanizing Iraqis around national identity, increasing opposition to regional intervention, and rejecting sectarianism, which has skewed the Government of Iraq's (GOI) governance, fiscal, and monetary policies for decades;

- Complicated governance and political trends, demonstrated by weak and absent service delivery;

- Economic and financial hardship, evident in delays to public employee salaries, the Central Bank of Iraq's decision to devalue the Iraqi dinar vis-à-vis the dollar by almost 20%, and an enormous deficit anticipated for the 2021 national budget; and

- Aggressive regional interventions, including increasing activities by military and political proxies.

These four dynamics have contributed to political turmoil and socio-economic unrest, giving rise to continuous sporadic demonstrations, entrenching state fragility, and threatening Iraq's wellbeing as a functioning country.

The United States has a strategic interest in a more stable Iraq, which would contribute substantially to a more stable Middle East. Many of the dynamics causing the transformation in Iraq are evolving in neighboring countries too, such as Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen, and have ripple effects across the region. Preserving the development of democratization and human rights, and ensuring the security of key energy and trade routes are of global interest. Accordingly, the Biden administration’s strategy in Iraq should focus on working with the GOI to address state fragility and strengthen domestic legitimacy and external sovereignty. Such an approach should empower civil society and enhance inclusive political and legal frameworks, especially in terms of women, youth, religious pluralism, and financial inclusion. The Biden administration should also support the GOI in advancing effective and actionable policies to diversify the economy and fight systematic corruption.

These long-term policy engagements translate into a few urgent actions that the Biden administration must take in its first 200 days. First, the U.S. should actively support the GOI to hold the early elections tentatively set for October 2021. If these elections are held as scheduled, it would represent the first time that early elections have been completed in Iraq as a direct result of public demands for better governance. Encouraging the GOI to keep its promise to hold these early elections will therefore play an important role in bridging some of the trust gaps between the public and government and enhance its legitimacy. Second, the U.S. government should contribute to consolidating the Iraqi state's sovereignty by providing technical expertise and financial assistance to the GOI to carry out the peaceful disarmament and integration of all non-state actors. This will curtail regional military proxies and consolidate the use of force in the state's security apparatus. Third, the U.S. should prioritize incentivizing the GOI to reactivate decentralization with the provinces and federalism with the Kurdistan region. Enhancing the two governing structures will facilitate addressing the pressing public demands for better service delivery and infrastructure projects to improve the education, health, and transportation sectors.

To that end, the U.S. should leverage its political capital, economic capabilities, and leadership role in international development through USAID and multilateral institutions like the World Bank, IMF, and the U.N. to operationalize an alliance-based strategy to coordinate policies with regards to Iraq and influential regional players. It is crucial to adopt a multi-actor collaborative approach to the upcoming U.S. engagement that emphasizes the notion that stability in Iraq and the broader Middle East requires a regional equilibrium of power to contain the current political and military proxy conflicts and conflict spillover.

As a new administration takes over in Washington, it is crucial to understand that political maneuvers in Iraq and the Middle East are based on political, economic, and geostrategic calculations, rather than traditional ideological positions. Accordingly, policies that address these needs will be more viable in the current Iraqi and Middle Eastern contexts.

Shahla Al-Kli is a non-resident scholar at MEI.