In the immediate aftermath of the assassination of Gen. Qassem Soleimani, head of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps – Quds Force, on Jan. 3, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei warned the U.S. of Iran’s “harsh revenge.” Just hours after Soleimani’s funeral, in the early morning of Jan. 8, Iran launched more than a dozen ballistic missiles at the Ain al-Asad airbase in al-Anbar Province in western Iraq, as well as at another airbase in Erbil in Iraqi Kurdistan. The Iranian leadership characterized the missile strikes as a “slap in the face,” emphasizing that “revenge is another issue” and was yet to come, adding that the ultimate goal was to rid the region of “the corruptive presence of the U.S.”

There has been much speculation around the timing, location, and the type (or form) of Iran’s promised revenge. Some of the possibilities that are broadly discussed include inciting acts of terrorism within the U.S. — hence the heightened alerts in major U.S. cities such as New York City and Washington, D.C. — attacking U.S. allies and their interest in the region, blocking the Strait of Hormuz, cyber warfare, and attacking U.S. bases and military personnel in the region.

However, some of these strategies are not in line with Iran’s ultimate objective of forcing the U.S. out of the region permanently. An Iranian-linked attack inside the U.S. would rally political and public opinion in support of the U.S. and its allies to go to war with Iran, leading to more deployment of U.S. troops to the region. Attacking U.S. allies in the Gulf and their interests would most likely prompt them to call for and finance a stronger U.S. presence in the region, making such a presence both legal and legitimate under international law.

What about the widely discussed strategy of blocking the Strait of Hormuz, a vital maritime chokepoint through which around one-third of global seaborne oil travels? Such a move by Iran would be tantamount to collectively punishing the world economy for the unilateral actions of the U.S. It would most likely result in the formation of a global coalition, probably led by the U.S., to confront Iran. Moreover, blocking the Strait of Hormuz or attacking energy facilities in the Gulf will inflict more pain on friendlier Asian economies, especially China, than it will on the U.S. This is an important consideration for the Iranian leadership. China has been an implicit ally of Iran in the era of U.S.-imposed sanctions and heightened hostilities toward Iran. Just days before Soleimani’s assassination China, Russia, and Iran held trilateral naval drills in the Gulf, moving the Sino-Iran relationships into a new gear. In a sign of how close bilateral ties have become, Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif visited China four times in 2019. The most recent visit took place on Dec. 31, just a few days before Soleimani’s targeted assassination, which the Chinese bluntly condemned as an “abuse of force” by the U.S. and a “dangerous U.S. military operation violating the basic norms of international relations.” Viewing China as an important ally in times of crisis and given its growing economic ties and interests in the region over the past two decades, Iran’s options for revenge will most likely be limited to those that have a minimal impact on the Chinse economy.

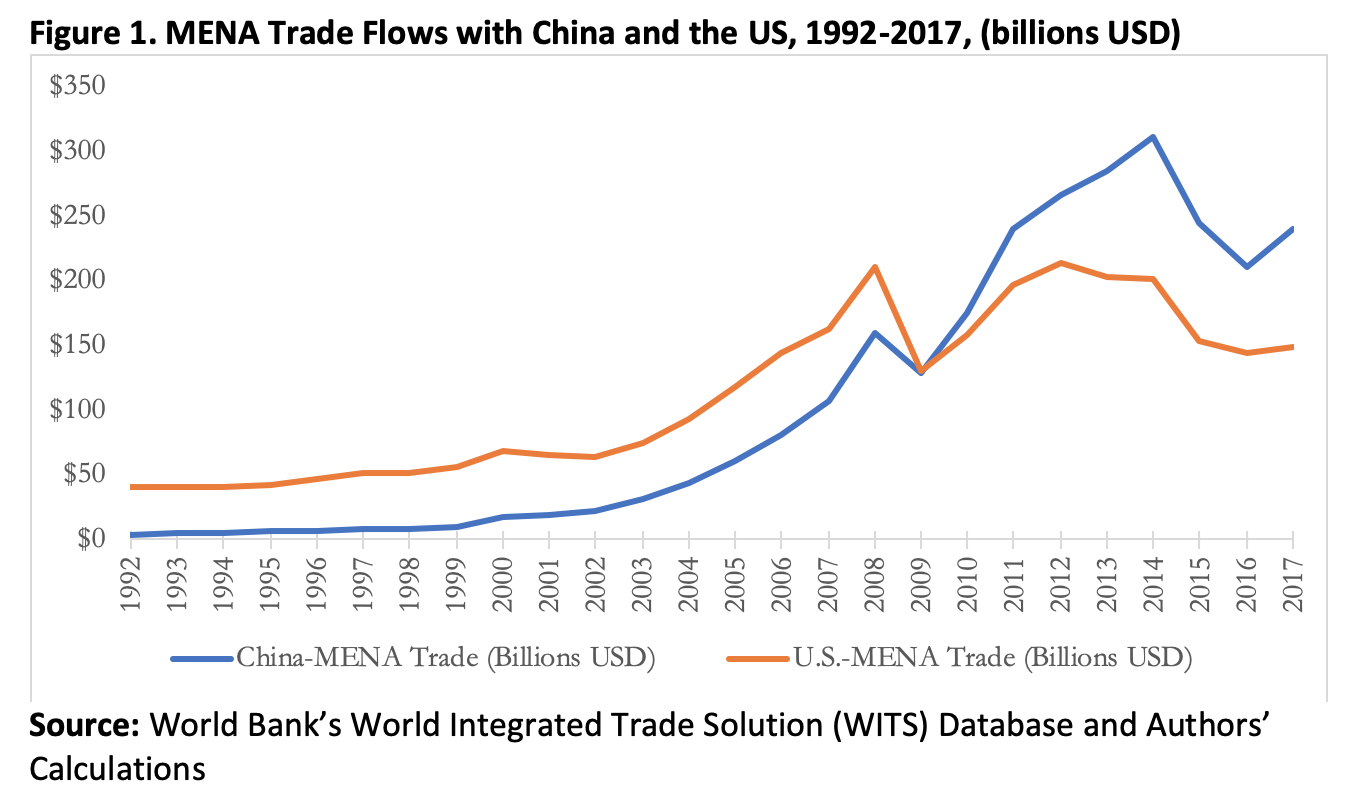

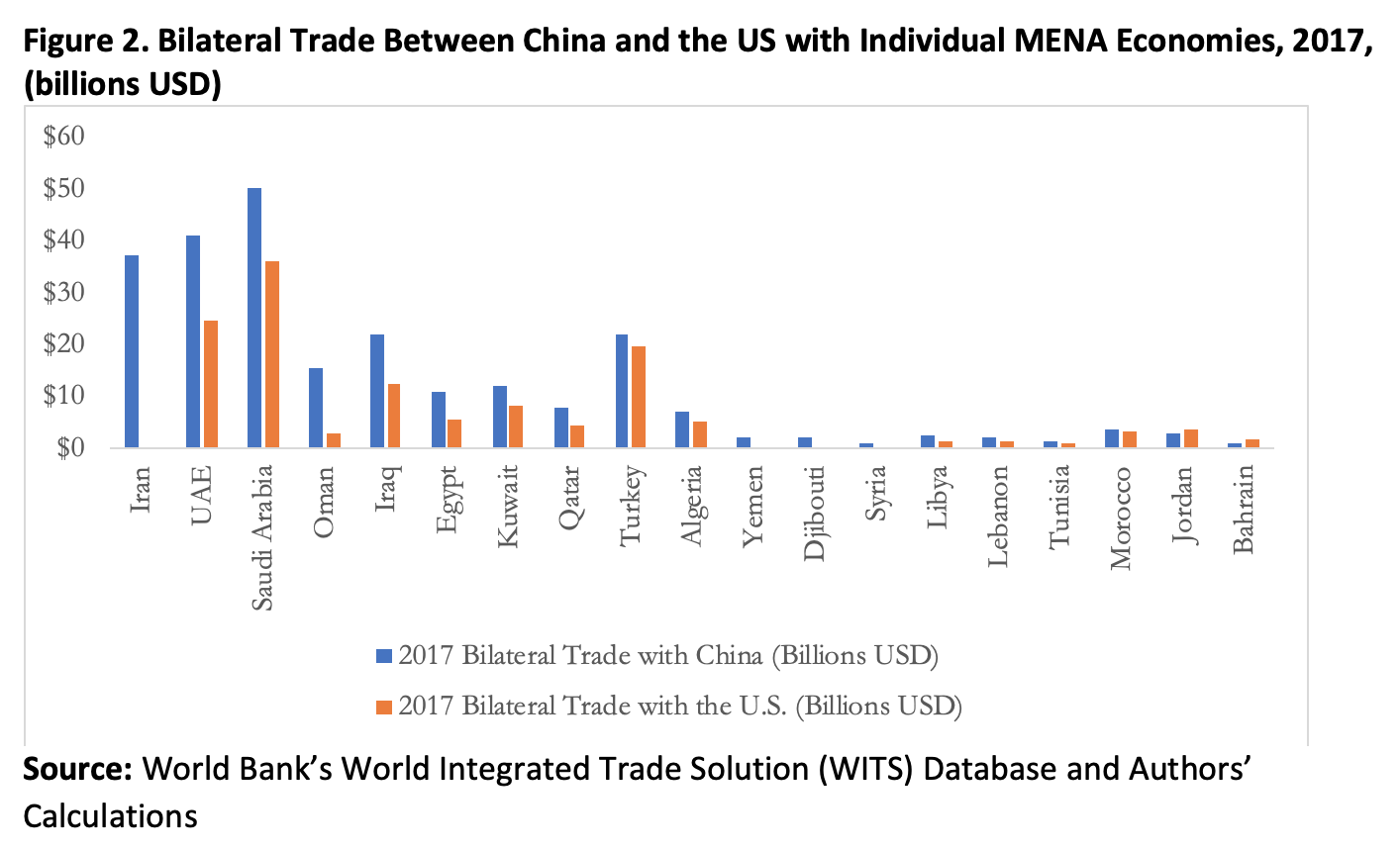

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2007-09, China has surpassed the U.S. as the largest trading partner of the MENA region and economies around the Gulf in particular (Figures 1 and 2).

In 2018, around 45 percent and 11 percent of Chinese imports of crude oil and natural gas were sourced from the Gulf countries, respectively. During the same year, the U.S. did not import any natural gas from the Gulf and less than 20 percent of U.S. imports of crude oil came from the region. Therefore, compared to the U.S., China is much more dependent on the oil and natural gas that travels through the Strait of Hormuz. This is also true for Japan, South Korea, India, and other emerging Asian economies that have been friendlier with Iran. As a result, blocking the Strait of Hormuz or inflicting serious long-term damage to the region’s oil facilities would not be an effective means of taking revenge. Such moves would likely backfire, generating global uproar that would strengthen the U.S. presence in the region while also doing much greater harm to Asian economies than the U.S. The Iranian leadership will want to avoid any of these outcomes as they work against Tehran’s main long-term objective of forcing the U.S. out of the Middle East.

Thus, it seems that the only real effective strategy in Iran’s “harsh revenge” campaign is to increase the human and financial costs of the U.S. presence in the Gulf. To this end, Iran will likely leverage its extensive network of sympathizers and proxies in neighboring countries and beyond to carry out attacks against U.S.-only targets. Not only would this approach be in line with the regime’s ultimate objective, it would also allow the Iranian leadership to make good on its threats incrementally, at the time and location of its choosing. In turn, this will keep U.S. personnel in the region on high alert for the foreseeable future, which can be very costly, from both a financial and a psychological perspective. At the end of the day, as the saying goes, “revenge is a dish best served cold.”

Amin Mohseni-Cheraghlou is an assistant professor in the Department of Economics at American University in Washington, D.C. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by ATTA KENARE/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.