The Russian invasion of Ukraine has been a watershed moment on so many levels for so many countries. Existing political, economic, energy, and transportation channels are being affected across western Eurasia. Countries are maneuvering to minimize the war’s detrimental impact while new trade synergies are being formed at a rapid pace. Most recently, Germany and Qatar signed a long-term energy partnership for the delivery of Qatari natural gas as the Germans look to reduce dependence on Russian supplies. Qatar’s reserves are located in the world’s largest gas field, which it shares with its northern neighbor, Iran.

The Iranians, too, have the option to harness the new economic opportunities that are emerging from Russia’s international isolation. But unlike in Qatar, the Islamist ruling class in Tehran is not driven by commercial common sense. Instead, it is captive to a set of anti-Western ideological priorities that means Iran will probably once again miss the train. But to be fair, it is not only Iran that is responsible for this situation. In the last 30 years, the United States and Europe have systematically marginalized the country from all major energy trade and transit projects that linked the broader Middle East to European markets. Perhaps the gravity of the Russian invasion of Ukraine will give the United States and Europe a reason to reconsider Iran’s economic ostracization. Even so, Tehran would have to play ball for a new Iranian-European energy and transit symbiosis to have any chance to succeed.

The last time Iran missed an opportunity like this was in the mid-1990s. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, a new great game ensued. Oil and gas producers from newly independent states in Central Asia and the South Caucasus looked for the best routes to European markets while avoiding Russia. Tehran was eager to play a part. Within a few weeks of the collapse of the Soviet Union, Iran and Ukraine signed a deal for 4 million tons of petroleum and 3 billion cubic meters of natural gas a year. They also signed an agreement with Azerbaijan for three natural gas pipelines that would run from Iran through Azerbaijan to Ukraine via a port on Georgia’s Black Sea coast. There was also talk of two separate oil pipelines that would take the same route. Not only could Ukraine be an end user of Iran’s oil and gas exports, but the country would also be a transit route to European markets.

Foreign Policy (subscription required)

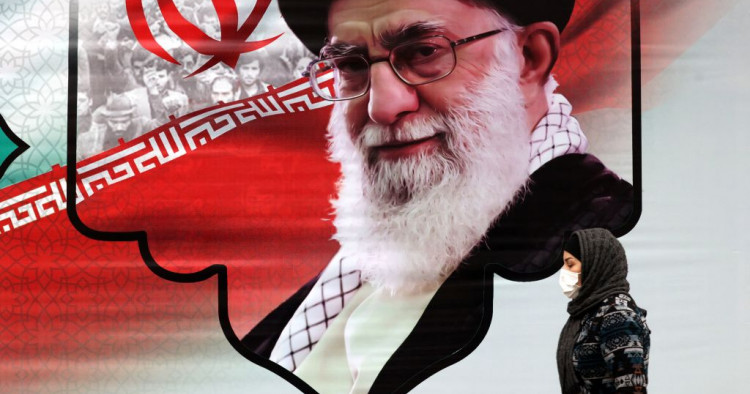

Photo by ATTA KENARE/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.