The core question for Iran watchers this year is the likelihood and nature of a renewed Iranian nuclear deal. However, the circumstances are very different and the respective bargaining power of the two sides does not mirror the negotiations in 2015. While Iran has used the suspension of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) to boost its nuclear enrichment activities and entrench its political influence in the various regional disputes (e.g. Syria, Yemen, Iraq, etc), the macroeconomic backdrop is considerably worse today and the regime more desperate for sanctions relief than it seems.

Donald Trump’s “maximum pressure” strategy may not have yielded any tangible political results, but the economic damage was more severe than Barack Obama’s sanctions in 2012 onwards. Iran’s GDP had been shrinking by double digits in the Iranian calendar year of 2018-19 and has simply decelerated its pace of recession since then. In fact, Iran is one of the few countries whose GDP growth in 2020 may not have been much different than the pre-pandemic, illustrating the scale of contraction occurring.

The damage obviously resulted from the lost oil export revenue, as during the years before the JCPOA. However, three features are very different this time around. First, GDP growth was not as frail in 2012-14 as in 2018-19 and it had already stabilized by the critical phase of the negotiations.

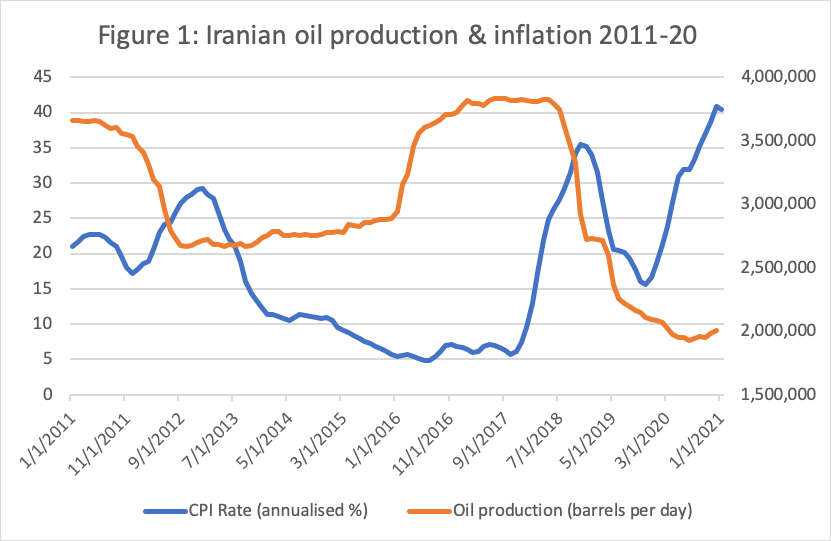

Second, Obama’s sanctions were not as impactful in terms of curtailing Iran’s oil exports and oil prices were much higher at the time. Pre-JCPOA, Iran was running a small fiscal deficit. Today its deficit is above 4%. Iran is not able to borrow from international capital markets, so running prolonged large deficits is not an option even in times of distress. As Figure 1 shows, oil production dropped by about 1 million barrels a day, whereas the drop this time around is nearly double that. One needs to bear in mind that lower oil prices also mean the residual earnings are even less. The JCPOA experience shows that Iran is very capable of quickly restoring production, hence commodity traders are fretting about a sudden return of 2 million barrels of Iranian oil. In total, this would amount to roughly $35 billion in export revenue, equivalent to 7-8% of GDP, which is nearly double the government’s estimated fiscal deficit this year. One need not read anecdotal evidence to know that Iran’s economic struggle is much more severe this time around and restoring public finances would be the first step out of the crisis.

And third, public perceptions and experience of the hardships are certainly greater now too. Figure 1 also shows that inflation reached similar levels in the pre-JCPOA era, but had largely been brought under control by the time negotiations started. The economic normalization gave Iranian negotiators breathing space to drive a hard bargain. This time around there is no sign of high inflation receding and any talks will take place in the context of economic misery at home.

In short, time — in terms of economic metrics — is not on Iran’s side in this round’s negotiation. The result should be a less favorable deal compared to the JCPOA as negotiators seek to gain relief before year-end.

Elliot Hentov is the Head of Policy Research with the Global Macro Policy Research team at State Street Global Advisors. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.