Contents:

- Amid growing Gulf investment, Egypt tries to maintain a tricky economic balancing act

- In Iraq, expect more talks, possible new violence

- Despite recent speculation, the prospects for Turkish-Syrian rapprochement remain distant

- Romania, France, and the UAE push to expand Ukrainian food export options in the Black Sea

- The US throws the Afghan financial system a lifeline

- Cairo Environment and Development Forum highlights Egypt’s COP27 priorities

Amid growing Gulf investment, Egypt tries to maintain a tricky economic balancing act

Mirette F. Mabrouk

Senior Fellow and Founding Director of the Egypt program

-

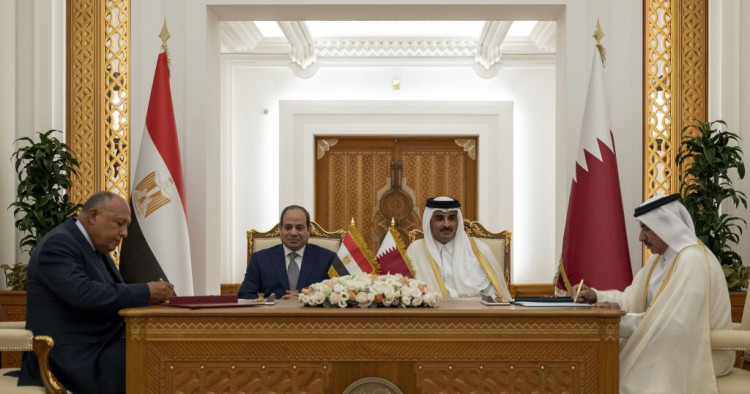

Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi’s visit to Qatar last week bore almost immediate fruit; three MoUs were signed, including one between the respective sovereign wealth funds.

-

While Egypt needs FDI, there are worries that outside investors may wind up controlling vital sections of the economy.

Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi made his first visit to Qatar during his time in office last week, following Qatari Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani’s visit to Cairo at the end of June. According to the Qatar News Agency, the visits heralded “a new era of relations between the two countries.”

Those relations had been tense since the removal of former President Mohamed Morsi by the military, after massive demonstrations against him and the Muslim Brotherhood in 2013. Following one diplomatic spat after another, in 2017, Egypt joined Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain in boycotting Qatar. That boycott was lifted in early 2021, and the countries have been taking increasingly energetic steps forward since.

Last week’s meeting in Qatar bore almost immediate fruit; three memorandums of understanding (MoUs) were signed, including one between the respective sovereign wealth funds. And on Saturday, Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly met with Sheikh Faisal bin Thani Al Thani, the chief of Asia-Pacific and Africa investments at Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund, the Qatar Investment Authority. Egypt is particularly keen to maximize its tourism development potential and during the meeting, Madbouly presented Al Thani with a plan to develop the area west of Alamein. According to Masrawy, Al Thani indicated that Qatar was interested in exploring investment in both existing structures and developing new ones.

A day later, Egypt’s transport minister, Kamel el-Wazir, and Abu Bakr Kondial of Maha Capital Partners, an investment arm of the Qatari sovereign wealth fund, signed an MoU to develop and upgrade the vital Port Said Port container terminal.

Last May, el-Wazir had announced a plan to merge multiple ports into one company to be offered on the Egyptian Stock Exchange, according to Mada Masr, including Ain Sokhna, Damietta, Alexandria, East Port Said, Safaga, and Adabiya.

There’s been a lot of interest in Egypt’s ports and the crucial Red Sea trade passageway. And Egypt is even keener on capitalizing on this attention. The country’s economy has been battered mercilessly; still struggling with the fallout from the pandemic, it was in poor shape to withstand the disastrous effects of the war in Ukraine. Hot money behaved the way it always does during periods of global instability, as foreign investors in the bond market fled for more stable developed markets, taking vital foreign currency with them. That global instability meant spiking prices, increasing the demand for scarcer foreign currency. To put one final boot in, much of the country’s rising debt is nearing maturity, placing even more of a squeeze on its foreign currency resources.

The influx of Gulf money — Saudi, Emirati, and now Qatari — has been seen as a lifeline for Egypt’s battered economy. That’s indisputable. However, that money is being referred to as loans and handouts, which is far from the case. Whereas in previous years the Gulf countries had placed generous deposits in Egypt’s Central Bank, helping to prop up the economy, they are now making investments; and like any investor, they will naturally require a return on their money. While Egypt needs foreign direct investment, there are worries that outside investors may wind up controlling vital sections of the economy. The Qataris have expressed interest in Port Said, and the Emirati firm Abu Dhabi Ports won a tender to manage Ain Sokhna on the Red Sea. According to Mada Masr, the security implications have now been presented to Egyptian President Sisi.

All new investment carries an opportunity cost. Having foreign firms manage ports means relinquishing a measure of control, and expanding tourist developments means keeping a close eye on the environmental strain and potential damage that development might do to natural resources. It’s a tricky balancing act.

Follow on Twitter: @mmabrouk

In Iraq, expect more talks, possible new violence

Robert S. Ford

Senior Fellow

-

The standoff between Shi’a Islamist groups will resume in earnest this week, with the Sadrist Movement on one side and the Coordination Framework, which is itself split, on the other.

-

Elements of a deal are visible, but there are plenty of details that can derail everything — and there is a real risk of renewed violence.

The standoff between Shi’a Islamist groups in Baghdad over the naming of a new government continues, and political maneuvering, which had slowed last week during the Shi’a religious pilgrimage of Arba’een, will resume in earnest this week. On one side of the ongoing dispute, the movement of populist cleric Muqtada al-Sadr insists that the existing parliament, elected in October 2021, be dissolved and that the current interim government oversee new elections. Confronting the Sadrists is the Coordination Framework (CF), a coalition of Shi’a parties that is itself split, as one Iraqi analyst explained on Sept. 18, between hawks and doves. The CF hawks, led by former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, want the existing parliament to convene promptly to choose a new president and a new prime minister with a new government enjoying full authority to run the country. The doves in the CF prefer to bring along the Sadrists by cutting a deal on a new government whose key role would be overseeing new elections.

Media reports over the weekend said a delegation that includes doves from the CF as well as representatives from Sunni Arab and Kurdish parties will call on Sadr in Najaf. It is not yet clear whether he is prepared to compromise on issues such as who would head a new cabinet and what its mandate would be. There are hints in the Iraqi media that the CF doves and their Sunni Arab and Kurdish colleagues would accept a compromise prime minister. Other sweeteners can also be thrown into the negotiating mix, including seats in a new cabinet and changes to the commission that would oversee the new election. Another crucial element to resolve the standoff is an agreement between feuding Kurdish parties over the new president since the other political groupings likely would ratify a unified Kurdish choice if there is also an advance agreement on a prime minister.

Elements of a deal are visible, but there are plenty of details that can derail everything. Hawks in the CF have not promised to compromise. One hawk told an Iraqi news service on Sept. 18 that the upcoming visit to Najaf was the “last chance” to bring Sadr along. While they can sharply disagree, Iraqi political leaders rarely resort to violence before they first plunge into long — sometimes seemingly interminable — discussions. If the hawks lose patience and push hard to reconvene the parliament to approve a new government, the risk of new Sadrist street action and renewed violence between Sadrist militias and militias loyal to the hawks is very possible.

Follow on Twitter: @fordrs58

Despite recent speculation, the prospects for Turkish-Syrian rapprochement remain distant

Charles Lister

Senior Fellow, Director of Syria and Countering Terrorism & Extremism programs

-

Though almost entirely unacknowledged, Syrian intelligence chief Ali Mamlouk has met several times with his counterparts from a number of regional adversarial states throughout the crisis.

-

Speculation about Ankara and Damascus reaching a modus vivendi may be partially driven by Russian narratives and in part by the Turkish government’s pre-election considerations.

Speculation continues to surround Turkey’s Syria policy following weeks of reporting around public comments in August by senior Turkish officials and more recent claims, citing unnamed sources, that Turkey’s intelligence chief held several meetings with his Syrian counterpart, both in Ankara and Damascus. While secret contacts between security leaders are not entirely new, the reported intensity of these meetings and the alleged facilitating role played by Russia does mark a change. Still, there remains no sign that the vast chasm between the two decade-long opponents is narrowing, suggesting a more nuanced reality may be at play.

Though almost entirely unacknowledged, Syrian intelligence chief Ali Mamlouk has met several times with his counterparts from a number of regional adversarial states throughout the Syrian crisis. In all likelihood, Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization (MIT) chief, Hakan Fidan, met with Mamlouk to discuss or negotiate the situation in northern and northeastern Syria, where both parties would like to see the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) weakened, if not ultimately crippled. It is also quite likely that Fidan has been scoping out the framework for any future rapprochement between Turkey and Syria — but in so doing, he will not be faced with any realistic path forward, for the obstacles remain insurmountable.

Since the fall of Aleppo in 2016 (which Turkey directly facilitated), Ankara’s Syria policy has been guided overwhelmingly by counterterrorism and border security concerns. For now at least, there is no sign that Damascus or Moscow are willing to greenlight any further Turkish incursion (Turkey’s immediate ask), while the likelihood that Ankara will relinquish the vast stretch of territory it occupies across northern Syria (Syria’s primary demand) remains inconceivable.

On border security, Turkey is acutely aware of the more than 4.5 million Syrians currently residing within that unstable Turkish-influenced northwestern zone, all of whom refuse to even consider returning to regime-controlled areas. On top of that, Turkey continues to host at least 3.5 million Syrian refugees, who retain the same complete aversion to regime rule. And to add to that pressure against normalization, Turkey is also the central guarantor of at least 50,000 armed opposition fighters and more than 10,000 militants within the jihadist group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham. Any Turkish re-embrace of Bashar al-Assad’s regime would catalyze a worst-case series of threats to Turkey’s national security, the effects of which would likely kill off any chance of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s re-election next year.

On the other side of the equation, Assad’s regime displays no sign whatsoever of softening its hostile stance toward Turkey — with state media and senior officials continuing to label Turkey a “war criminal” state, “occupying” Syrian territory at the behest of “terrorists.” Behind the scenes however, there is little reason not to engage delicately on intelligence levels and every motivation to allow a public narrative to continue that suggests Damascus’s most significant state challenger may be considering re-engagement.

Ultimately, the roots of the recent speculation are more likely to lie, in part, in Russia’s desire to create an impression of foreign policy achievement amidst a pitiful war in Ukraine. A further source may be Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), which needs to assuage and align on the surface with concerns expressed by some of its domestic voting base and supporters of its rival parties’ hostility to Syrian refugees and Turkey’s spending and investments in northern Syria. Turning policy activities driven more by optics into reality will be nigh on impossible for Russia and highly dangerous for Turkey.

Follow on Twitter: @Charles_Lister

Romania, France, and the UAE push to expand Ukrainian food export options in the Black Sea

Iulia-Sabina Joja

Director, Frontier Europe Initiative; Project Director, Afghanistan Watch

-

Last week, France and Romania signed an agreement focused on improving transit options for Ukrainian grain exports via Romania’s land, sea, and internal waters.

-

Dubai-based company DP World is building a new terminal at the Romanian port of Constanța, which has been overloaded since Russia’s full-scale re-invasion of Ukraine.

Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, which blocked maritime exports of Ukrainian grain, created a food crisis across the developing world by acutely increasing prices and heightening widespread fears of shortages. In August, Turkey and the United Nations brokered a deal that assured the safety of grain export ships leaving Ukraine’s northwestern Black Sea ports. But this arrangement only managed to partially alleviate the crisis: Much of Ukraine’s grain remained blocked and the regional infrastructure experienced heavy congestion. Under the pressure of war and thanks to Romanian leadership, however, critical developments are taking place, aimed at improving Black Sea infrastructure to aid the export of Ukrainian food products to developing countries, including in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). In particular, governmental pledges from France and private investments from the United Arab Emirates are now contributing to the brisk expansion of transport infrastructure at the border between Romania and Ukraine.

Last week, France and Romania signed an agreement focused on improving transit options via land, sea, and internal waters, in the Danube River Delta and along Romania’s Black Sea coast. The bilateral deal is comprehensive and promises short-term improvements as well as medium-term investment planning — encompassing the Danube-Sulina canal, the Danube port of Galati (less than 10 miles from the Ukrainian border), the Black Sea port of Constanța, and land border points — all with an eye toward facilitating increased grain shipments. Since the start of Russia’s full-scale re-invasion of Ukraine in late February, Romanian transport facilities have been critical to enabling at least some Ukrainian grain exports; but the transport infrastructure has been overloaded. Along with Ukraine, Romania is itself one of the world’s largest exporters of agricultural products. But if Romania, in cooperation with France, can secure sufficient medium-term investments, this should help to address future food crises in MENA and the rest of the developing world.

The other recent infrastructure development aimed at facilitating grain exports from the Black Sea region involves DP World, an international logistics firm and port operator based in Dubai. In the works since June, DP World will build a new terminal for the Romanian port of Constanța, which has been overloaded since Russia invaded its neighbor earlier this year. To be finalized next summer, the new terminal will help Romania handle more exports, both of its own products as well as of Ukrainian ones, thus highlighting the strategic importance of the Black Sea region for global transport and supply chains.

Follow on Twitter: @IuliJo

The US throws the Afghan financial system a lifeline

Marvin G. Weinbaum

Director, Afghanistan and Pakistan Studies

-

The Switzerland-based Afghan Fund is designed principally as a means to aid the Afghan people without benefiting a sanctioned Taliban government.

-

The monetary windfall, as large as it is, cannot by itself revive the Afghan economy. But it should contribute substantially to stabilizing it.

An Afghanistan deep in humanitarian and economic crisis found some relief last week with the announcement by the Biden administration that $3.5 billion of the $7 billion in frozen Afghan central bank reserves in the U.S. would be released to a newly created fund. The Switzerland-based Afghan Fund is designed principally as a means to aid the Afghan people without benefiting a sanctioned Taliban government. This new instrument is expected, among other tasks, to manage targeted disbursements to cover debt payments, purchase critical imports, improve eligibility for international development aid, and print new currency, acting in effect much as a state’s central bank would. The direct recapitalization of the current government’s central bank was ruled out after U.S. representatives failed in negotiations with the Taliban to come to an agreement on the necessary safeguards to ensure that technocrats running the bank could be shielded from political interference.

Many of the details about the Afghan Fund’s operations remain unclear or have yet to be worked out. Complicated issues include how it will relate to other financial institutions, such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and International Monetary Fund, and whether it will be able to interact with other countries’ central banks. (The Basel-based Bank for International Settlements is slated to provide the Fund with financial services and assist in implementing policies, but it will not be involved in decision making.) How smoothly the board of trustees designated to manage the Fund will function is also an open question. The board, which will consist of two Afghans, a U.S. official, and a Swiss representative (and possibly additional members), will require unanimity in making decisions. Could this seriously impede the ability of the trustees to reach agreements? Might their work be complicated by the fact that while both named Afghan trustees have distinguished careers in banking, like practically all once-prominent public figures in the previous two-decade-long republic, they also come with political baggage?

The Kabul regime has announced its objections to the creation of a Switzerland-based trust in which it will have no input. The Taliban express concern that the new funds may be used to support humanitarian programs rather than directly strengthen the country’s financial system. The government still hopes to recover the remaining $3.5 billion in U.S.-held assets as well as the $2 billion in European banks. The final disposition of the U.S.-retained funds remains uncertain. They will likely be tied up for the foreseeable future in U.S. courts as the families of victims of the Sept. 11 attacks pursue their claims to the frozen reserves.

The monetary windfall, as large as it is, cannot by itself revive the Afghan economy. But it should contribute substantially to stabilizing it. If the Fund succeeds in steadying the economy and in lessening the current crises, the ruling Taliban’s staying power will almost inevitably be strengthened. But this may be a necessary price to pay for averting the collapse of the economy and the resulting toll it would take on the wellbeing of the Afghan people.

Shizah Kashif, a research assistant to Marvin G. Weinbaum, assisted with this article.

Follow on Twitter: @mgweinbaum

Cairo Environment and Development Forum highlights Egypt’s COP27 priorities

Mohammed Mahmoud

Senior Fellow and Director of the Climate and Water Program

-

The Sept. 11-13 climate forum in Cairo provided another opportunity to get a better sense of Egypt’s priorities for COP27, which the country will host in November.

-

Egypt remains committed to putting African concerns — namely climate resilience solutions — to the forefront at COP27.

The Environment and Development Forum 2022, bannered as “The Road to Sharm el-Sheikh Climate Change COP27,” took place in Cairo from Sept. 11 to 13. The forum was organized by the Arab Water Council with support from the Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Environment. Senior representatives from 30 countries attended. The forum’s purpose was to discuss the impacts of climate change as well as the adaptation and mitigation measures that could be utilized to address those impacts across multiple sectors and themes, including water and food security, carbon emissions controls, alternative forms of clean and renewable energy, and environmental preservation and protection.

Last week’s forum provided another opportunity to get a better sense of Egypt’s priorities for the U.N. Climate Change Conference (27th Conference of the Parties, COP27), which the country will host on Nov. 6-18. In Cairo, comments from Egyptian senior officials and experts confirmed, and in some cases elucidated, what will be the high-priority issues for Egypt at this year’s climate conference.

Emphasizing adaptation, not just mitigation: While highlighting that shifting to renewable sources of energy has become a priority for the Arab world (as a means to reduce carbon emissions), Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry also recognized the urgency of adaptation as a necessary function to deal with the effects of climate change.

Water scarcity is a top concern: The new minister of water resources and irrigation, Hani Sewilam, stressed how impacts to water supply due to climate change cascade into shortages of drinking water as well as volumes required for agricultural use and industrial production. In addition, he elaborated on Egypt’s particular vulnerability when it comes to water resources — with added emphasis on its extreme dependance on the Nile — while emphasizing the need for more water infrastructure (desalination and treatment plants) and inter-country cooperation.

Diversifying climate financing and investments: The push for more adaptation, especially for water and food security, creates a greater urgency for more efficient climate funding mechanisms. Mahmoud Mohieldin, the United Nations’ high-level climate change champion for Egypt, advocated for broadening climate investments in adaptation and the water and energy sectors, specifically highlighting projects beyond just reducing carbon emissions. In that same vein, he also urged less reliance on carbon markets and green bonds for financing, not just on borrowing.

Egypt remains committed to putting African concerns to the forefront at COP27 and to representing the continent’s interests at the conference. All of these key issues have one aspect in common: They are the most pressing challenges for almost all developing countries. As such, the biggest expectations for COP27 will be whether the high-level gathering can deliver progress in areas that can increase climate resilience for the most vulnerable nations.

Photo by AMIRI DIWAN OF THE STATE OF QATAR/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.