Contents:

- Iran is on the agenda as Lavrov heads to Riyadh for GCC talks

- Egypt rolls out its new national climate change strategy

- Sharif’s caretaker government finds little respite from Khan’s unrelenting attacks

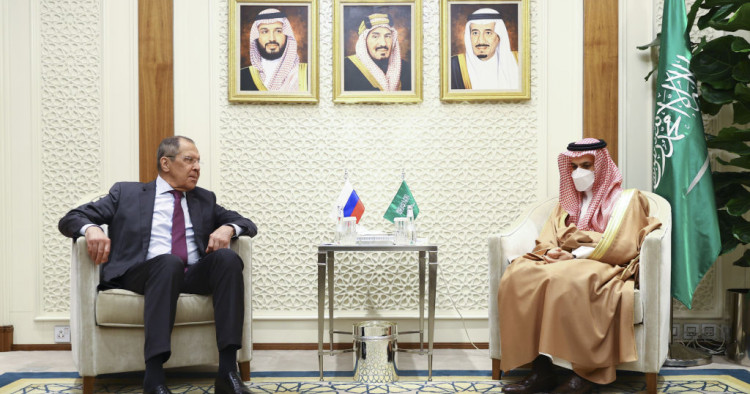

Iran is on the agenda as Lavrov heads to Riyadh for GCC talks

Alex Vatanka

Director of Iran Program and Senior Fellow, Frontier Europe Initiative

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov is due to meet his counterparts from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) on June 1 in Riyadh. This high-profile visit comes as Moscow is scrambling to compensate for the loss of economic links to Western markets due to sanctions. The Gulf states have not picked sides in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, but they do have a horse in this race given the global food and energy security dynamics shaped by recent supply disruptions.

Trade, including assurances of the supply of Russian agricultural products to Middle Eastern states, is on the agenda. Oil production volumes is another topic for consultation, especially in light of the EU’s decision to implement a partial oil embargo on Moscow. Russia and the Gulf states are among biggest oil producers in the OPEC+ syndicate, and have considerable influence on oil prices.

But it is likely the question of Iran that will be the hardest of bargains. As a collective entity, the GCC will wonder what Moscow’s ideas are for breaking the deadlock at the Iran nuclear talks in Vienna. The GCC states will also listen politely to Lavrov as he likely once again floats Russia’s concepts for a security architecture for the Persian Gulf region. What would be a departure from the past is if Russia and the Gulf states can agree on a basic understanding about how to handle Iran. This does not exist today — and it’s not Russia’s fault.

The GCC states have varying relations with Tehran. Among the six GCC states, two — Oman and Qatar — are keen to bring Iran out of international isolation and act as Tehran’s mediators with the West. Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi was just in Oman, where a number of new agreements were signed. Qatari Emir Sheikh Tamim was recently in Tehran and afterwards traveled to the Munich Security Conference, where he spoke about the need to bring Iran back in from the cold.

Three GCC states — Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain — are far more troubled by Tehran’s regional agenda. Kuwait is somewhere between the two poles within the bloc. Lavrov’s visit to the GCC is therefore a two-way mission. He will let the GCC states know that their rejection of sanctioning Russia is appreciated in Moscow while also urging greater trade and economic cooperation. Given their internal differences, the Gulf states do not have one single “ask” from Lavrov. But they surely hope the Russians have enough clout to help push Iran in the direction of accepting that it needs to have a qualitatively different conversation with its Gulf neighbors about their security concerns regarding its actions.

Follow on Twitter: @AlexVatanka

Egypt rolls out its new national climate change strategy

Mirette F. Mabrouk

Senior Fellow and Founding Director of the Egypt program

Egypt’s governments often respond well to deadlines. In this case, it’s a double header: both the fast-approaching U.N. Climate Change Conference (COP27), which Egypt is hosting in Sharm el-Sheikh this November, and, more importantly, the rapidly ticking environmental clock of climate change itself.

Possibly as a result of these reminders, the National Council for Climate Change asked for the upcoming National Climate Change Strategy 2050 early. On May 19 the government launched the new strategy at an event headlined by the prime minister, Mostafa Madbouly, and attended by the minister of environment, Yasmine Fouad, and several high-ranking U.N. officials.

This isn’t Egypt’s first foray into climate change policy; the early 1990s saw a massive, if low key, effort to transition public vehicles and taxis from gasoline to compressed liquefied natural gas, and the first Climate Change Strategy was presented in 2011, followed by the country’s Low Emissions Development Strategy in 2018. There has, however, been a significant uptick in both the quantity and quality of the efforts and the extent to which they’ve been incorporated into the country’s development planning. Egypt’s minister of international cooperation, Rania al-Mashaat, rarely kicks off a presentation without emphasizing Egypt’s efforts to develop and implement domestic programs that achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It makes for good business but it has also become a stark necessity.

Like the vast majority of emerging economies, Egypt is grappling with the consequence of the actions of the developed world — namely Europe, the U.S., China, and India. Africa produces less than 3% of global emissions. And while developed countries have pledged $100 billion to help clean up their mess, that money has not yet been delivered.

At the launch of the new climate change strategy, the PM pointed out that while Egypt produces just 0.6% of global emissions, it is extremely vulnerable to creeping threats due to climate change, which makes the new strategy all the more urgent.

According to Minister Fouad, who presented the strategy, it has five main goals, with cross-cutting tools and themes.

The first is the sustainable economic growth and low-emissions development in a number of sectors, primarily by increasing reliance on renewable energy sources, reducing fossil fuel emissions, and implementing sustainable consumption and production models to effectively reduce greenhouse gasses emitted as a result of various everyday activities.

Secondly, the strategy aims at developing “resilience and adaptability” to mitigate the negative impacts of climate change by protecting the population and the country’s ecosystems and natural resources. This aim also requires efficiently working toward an adaptable infrastructure and flexible services.

The next goal centers on the tricky task of defining the roles of relevant governmental bodies and other parties and, most importantly, improving governance for implementation. It’s also designed to tackle improving Egypt's international standing in terms of climate change action to attract more investment and green financing opportunities. It segues with the country’s ongoing efforts to encourage green investment; a joint U.S. Chamber of Commerce/American Chamber of Commerce business delegation to Egypt in mid-May, for example, explored cooperation and investment in green technology and business.

The strategy’s fourth goal aims at improving economic infrastructure to better accommodate financing climate-related activities and programs, as well as promoting domestic instruments that prioritize adaptation measures, like green banking and credit lines, while enhancing the private sector’s participation in financing climate-related activities and creating “green jobs.”

The final goal leans toward the “helping those who help themselves” line of thinking. It involves enhancing scientific research and the transfer of technology and knowledge across sectors to mitigate the negative impacts of climate change. This goal also involves the less scientific but no less complex aim of ensuring direct government/public communication on climate-related matters and environmental awareness across society.

The strategy is part of a larger effort on climate change; civil society groups are being roped in on both mitigation and adaptation efforts, particularly on water resources, agriculture, recycling, and resource allocation.

The efforts are timely, but also integral to Egypt’s survival. While the country is battling the detrimental effects of climate change, it’s having to balance those efforts with development. Egypt’s significant foreign debt, decreasing foreign exchange reserves, and possible associated economic and political risk, largely a result of global economic fallout from the Ukraine invasion, led Moody’s to cut its outlook from stable to negative last week. However, the country maintained its “B2” rating due to the government’s “proactive crisis response and track record of economic and fiscal reform,” according to Moody’s.

If Egypt wants to move beyond firefighting toward a healthy sustainable development track, it will require a large dose of that proactivity.

Follow on Twitter: @mmabrouk

Sharif’s caretaker government finds little respite from Khan’s unrelenting attacks

Marvin G. Weinbaum

Director, Afghanistan and Pakistan Studies

Political tensions in Pakistan briefly eased last Friday as former Prime Minister Imran Khan agreed to hold talks with the Shehbaz Sharif government to set a date for fresh national elections. This decision seemed to avert further confrontation with Islamabad’s police, who had blocked thousands of Khan’s avid party supporters from occupying an area uncomfortably close to key federal government buildings in the capital. With Khan’s plans for an indefinitely long sit-in having fizzled out, he appeared to display a rare pragmatism by agreeing to the political cooling off, probably at the urging of Pakistan’s military. But hopes for a negotiated deal remain dim as a defiant Khan continues to threaten another round of protests and has undertaken a new line of attack against the government over charges of police brutality.

Even as he agreed to talks last week, Khan issued an ultimatum that there must be an agreement on a June date for holding new elections within six days. Khan is anxious to feed off the enthusiasm generated by weeks of massive rallies and speeches offering a steady diet of xenophobic, conspiracy-laden rhetoric. If forced to wait months for elections, his campaign could lose much of its luster, especially if blockages and other activities begin to take a heavy toll on the country’s economy. An almost inevitable increase in bloodshed also carries with it the danger of a military intervention that would upend the democratic process. For its part, the Sharif government seeks to delay elections until August 2023, during which time it hopes to establish a record of accomplishments to take to the voters. But if in that time the government fails to control the country’s rampant inflation and has to yield to IMF demands for unpopular budget-tightening measures in order to avoid defaulting on debt, Sharif and his party will be held responsible. Also, with Khan openly trying to divide his political opponents, the longer the wait until elections, the greater the danger of defections from Sharif’s loosely knit governing coalition.

Whenever an election is scheduled, no opposition political figure can begin to match Khan in charisma or ability to deliver populist messages appealing to nationalism and religion. Khan’s personal appeal will not, however, necessarily rub off on his party’s candidates competing for national and provincial assembly seats. Pakistan’s use of plurality-based, single-member districts ensures safe parliamentary seats for regionally and locally strong parties. Elections in Pakistan must also take into account possible large-scale voter manipulation. But whatever the outcome, the defeated parties in Pakistan can be expected to refuse to accept the legitimacy of the new government.

Malavika Radhakrishnan, research assistant to Marvin G. Weinbaum, assisted with this article.

Follow on Twitter: @mgweinbaum

Photo by Russian Foreign Ministry / Handout/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.