Contents:

- Three US policy questions on America’s terrorism charges against Hamas

- Netanyahu holds firm as pressure builds to bring hostages home: Déjà vu over and over?

- Algeria: Status quo reconfirmed

- BRICS membership may not be a quick panacea for Turkey’s economic problems

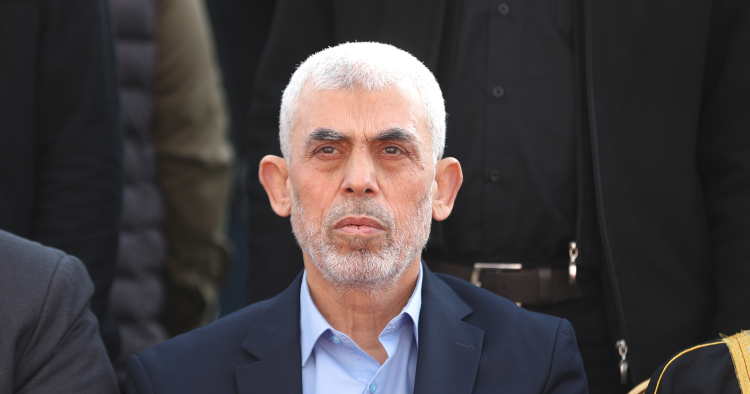

Three US policy questions on America’s terrorism charges against Hamas

Brian Katulis

Senior Fellow for US Foreign Policy

-

The US Justice Department’s terrorism charges against Hamas leaders for the Oct. 7 attacks were an expected if belated move to hold terrorists to account for their actions.

-

The indictment reminds the world of the nature of Hamas and raises three important questions for US policy on Palestine regarding 1) the short-term impact on diplomatic negotiations, 2) Hamas’ future role in Palestinian politics, and 3) post-war governance structures for Gaza.

Last week, the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) indicted six senior Hamas leaders on a series of charges, including conspiring to murder Americans and to offer material support for terrorist actions. Hamas started this latest war by attacking Israel and killing around 1,200 people, of whom at least 40 were US citizens; and the US government has filed criminal charges against terrorist groups responsible for killing Americans in the past. Three of the leaders charged in this indictment are already dead, and it seems unlikely that the rest will ever be brought into a US court for trial. In the eyes of some people, this move comes as a little too little and a little too late to do any good.

Nevertheless, there are many reasons why the United States would issue these indictments, including the moral imperative of “naming and shaming” those responsible for terrorist actions that kill Americans and spark conflicts like the current brutal war in the Middle East, which has raised regional and geopolitical tensions, exacerbated by Israel’s military response and lack of a clear plan for ending the war. At a time when some Americans appear confused about how this war began and how complicated it is to end the fighting, the DOJ charging document offers a useful reminder, while spotlighting what impact those initial attacks had on fellow US citizens.

Additionally, the news of the indictment raises three important policy questions for the United States as the administration formulates its near- and longer-term plans pertaining to the future of Palestine and Israel:

1. How might the indictment impact short-term diplomatic negotiations to secure a cease-fire and gain the release of hostages held by Hamas? One of the figures indicted is Yayha Sinwar, the current leader of Hamas, who is now the key decisionmaker on sensitive cease-fire talks that have failed to produce results for months. The Biden administration has made the cease-fire and hostage release deal the central focus of its diplomacy for many months now; but this diplomacy has failed to produce meaningful outcomes, as this assessment I wrote with colleagues at the Middle East Institute argues. Now, the Biden team may be reluctant to move forward with a renewed push for talks as Hamas has issued additional demands and the Israeli government remains internally divided about how to get hostages home and ensure Israel’s security.

2. What future does Hamas have in internal Palestinian politics? The US indictment primarily serves as a reminder that Hamas is a terrorist organization, but the group continues to play a role in intra-Palestinian politics at the same time. Hamas maintains some fairly strong public support among Palestinians, according to polls conducted since the war began. And some analysts have argued that Hamas will remain a key part of Palestinian politics after the war is over. If that’s the case, it is difficult to see any future US administration willing to deal with a movement whose leaders were indicted for terrorist actions that killed Americans.

3. What are likely post-war governance structures for the Gaza Strip? Related to intra-Palestinian politics is the question of which forces will govern the Palestinian people after the war is over, assuming the war doesn’t render the Gaza Strip entirely uninhabitable. Before Oct. 7, some Palestinians had lifted their voices in strong criticism of how Hamas had ruled in the years since it took power by force in 2007 — and this conjures up important questions about which voices might be included in the conversation about who should govern Gaza after the war is over.

The DOJ’s indictment of Hamas figures last week isn’t a major policy move on its own, but it does raise important questions for the future of US policy on Palestine.

Follow: @Katulis

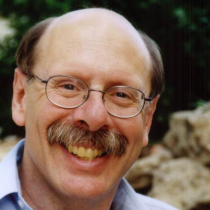

Netanyahu holds firm as pressure builds to bring hostages home: Déjà vu over and over?

Paul Scham

Non-Resident Scholar

-

There is good reason to suspect that neither Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu nor Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar sees any reason to compromise on a cease-fire, today or over the next few months.

-

Seventy-eight percent of Jewish Israelis are pessimistic about the near-term chance of a cease-fire agreement that would lead to the release of the hostages; and the US government is warning that the latest version of the deal may be the last.

Saturday night, Tel Aviv saw the latest round of what had become weekly (recently daily) demonstrations to pressure the Israeli government to work more effectively for the release of the remaining Israeli hostages held by Hamas in the Gaza Strip. The rally organizers claimed 500,000 demonstrators showed up in Tel Aviv alone, with hundreds of thousands more around the country. Whether or not that figure is entirely accurate, the throngs of demonstrators have unquestionably multiplied since six Israeli hostages were found dead on Sept. 1, with all indications that they had been executed by Hamas as the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) closed in.

One man has been the focus and target of all the demonstrations: Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who alone appears to be making Israel’s decisions regarding the deals being tirelessly produced by the Americans, the Egyptians, and the Qataris. Despite the numbers of protesters in the streets, so far at least he seems to be holding on to the number that ultimately matters: support by 63 of the 64 Knesset members (out of 120) comprising the government’s majority. The one possible exception is the minister of defense, Gen. (ret.) Yoav Gallant, who, a Haaretz correspondent recently wrote, is the only member of the inner Security Cabinet “thinking about the hostages.” He has argued vehemently that Israel need not retain control of the “Philadelphi Corridor,” the narrow strip at the edge of Gaza’s southern boundary, up against the Egyptian border. Many Israelis and others assert that Netanyahu deliberately inserted this and other landmines into Israel’s negotiating positions — and that Hamas has done the same.

Reportedly, Israel’s chief negotiators, Mossad Chief David Barnea and General Security Services (“Shin Bet”) head Ronen Bar, as well as the top IDF generals, see no reason to hold on to the corridor in the face of almost certain death for many, if not all, of those hostages who remain alive.

There is good reason to suspect that neither Netanyahu nor Yahya Sinwar, now Hamas’ undisputed head, sees any reason to compromise on a cease-fire, today or over the next few months. Netanyahu knows that the far-right members of his coalition, led by Ministers Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich, are likely to withdraw from the government if a cease-fire is accepted. That would almost certainly lead to new elections, which he would probably lose. At least as important is the pending high-level commission to investigate the security lapses that led to the Oct. 7 attack by Hamas, in which he would be implicated. Then there is his trial for fraud, breach of trust, and bribery, stayed after the Oct. 7 attacks. Continuation of the status quo might seem preferable to those consequences. His base largely still supports him. Perhaps a different decision might be made in November, when the results of the American presidential election become known.

Sinwar may have come to a similar conclusion. With no accountability to the population of Gaza, and with Israel’s standing in the world sinking ever lower and sympathy for the Palestinian cause growing ever higher, he may feel he can afford to wait for a cease-fire that provides for an Israeli withdrawal. Like Bibi, Sinwar has been accused of changing Hamas’ negotiating stance by introducing ever more onerous conditions. In addition, he may be hoping that the unstable conditions on Israel’s northern border could explode into a full-scale war with Hezbollah or even Iran, thus relieving the pressure on Hamas. However, William Burns, head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), reportedly maintains that Sinwar is under pressure to end the war. Very likely, both are true.

While the anger in the Israeli street has grown, there is a deep cynicism among all parties about the chances of a deal. Seventy-eight percent of Jewish Israelis are pessimistic about the near-term chance of a cease-fire agreement that would lead to the release of the hostages. Officially, the White House is optimistic; but there are warnings that the current version of the deal, to be floated this week, may be the last.

As the cliché goes, elections have consequences. Sixty-three votes in the Knesset trumps over half a million citizens in the streets.

Algeria: Status quo reconfirmed

Robert S. Ford

Senior Fellow

-

As was widely expected, Abdelmadjid Tebboune easily won Algeria’s Sept. 7 presidential election, with official results suggesting he had secured around 95% of the vote; in the absence of a truly competitive race amid widespread government interference, the election was more of a referendum on the incumbent.

-

The weak voter turnout, estimated at only about 23%, is likely to give Tebboune little leverage against the Algerian army, and no major changes in policy are expected.

Algeria’s national election agency said late on Sept. 7 that President Abdelmadjid Tebboune had won 5.3 million votes out of 5.6 million cast for the three candidates in the presidential election. Tebboune’s easy victory was no surprise. His two opponents, one an Islamist and the other a liberal politician, each represented real constituencies in Algeria, but the government interfered in the authorization of candidates to oppose Tebboune and in the conditions surrounding the campaign. Notably, Tebboune’s campaign director was the Algerian minister of interior. There were no debates, and the opposition candidates held few rallies. Amnesty International, on Sept. 2, condemned the government’s “brutal crackdown on human rights, including the rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association in the run-up to the election.” The government has imprisoned hundreds of opposition politicians, journalists, and activists and squashed all opposition press inside the country. There is less space for genuine political debate now than at any time since the large national protests that shook Algeria in 1988.

In the absence of a truly competitive race, the election was more of a referendum on Tebboune himself. The 5.6 million votes cast for the three candidates from a national voter list of 24.5 million suggest turnout of only about 23%, the lowest in any Algerian presidential election ever. (It also indicates that only 22% of Algeria’s potential voters voted for him.) Aware of the sensitivity of the voter turnout number, the election agency claimed the turnout was 48% without providing data about how it reached this peculiar figure. Many observers said that public despair with Algeria’s decades-long unemployment and housing shortage, combined with the certainty of a Tebboune victory, led most Algerians to stay home. Young Algerians at a recent soccer match in the country’s second-largest city, Oran, shouted en masse during the game, “I won’t vote; I’ll flee the country on a small boat,” referring to the thousands of mostly young men who try to cross the Mediterranean illegally.

France, Turkey, Syria, and Tunisia quickly sent congratulatory messages to Tebboune after the election result was announced. Washington issued a tepid statement congratulating Algeria for holding the election and pledging to continue to work with it on bilateral relations; Washington did not mention Tebboune specifically. The Algerian president will change his cabinet next, but there is little prospect of any dramatic shifts in state policy. Instead, the low turnout indicates Tebboune will gain little leverage against the Algerian army, which dominates major political decisions behind the scenes.

Follow: @fordrs58

BRICS membership may not be a quick panacea for Turkey’s economic problems

Gönül Tol

Director of Turkey Program and Senior Fellow, Black Sea Program

-

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan presumably thinks BRICS membership will help him secure concessions from the West or else get what he needs from fellow BRICS members.

-

But the BRICS bloc is divided both on the question of further enlargement and on Turkish membership in particular; China is concerned about Turkey’s investment climate, and the group’s recently added Middle Eastern members vying for regional influence with Ankara.

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member Turkey has applied for membership in BRICS, a group of developing countries founded in 2006 by Brazil, Russia, India, and China, and soon thereafter joined by South Africa. With Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the United Arab Emirates having been formally accepted this past January, BRICS now forms one of the world’s most important economic blocs, representing more than one-quarter of global GDP and 42% of the world’s population. The grouping seeks to challenge the Western-led order and provides a platform for discussing problems facing the Global South. Emerging middle powers like Turkey see BRICS as a tool to secure green-energy investments, technology transfers, and weapons deals as well as to recalibrate their relations with the West. As the Russian invasion of Ukraine and increasing tensions between China and the United States draw the world toward a new cold war, countries like Turkey are using their simultaneous ties to the West and the Russia-China-led bloc to advance their interests.

Turkey has reasons to be frustrated with its Western allies. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is facing one of the toughest moments in his long tenure due to the country’s worsening economic problems. After last year’s elections, Erdoğan abandoned his failed policy of holding down borrowing costs, tried to mend ties with the West, and appointed a new economic team to reassure foreign investors who have ditched Turkey in recent years. Yet the country’s economic woes have continued to deepen, and Turkey’s relations with the West remain strained. Last week, Turkey’s foreign minister attended a meeting of European Union ministers for the first time in five years to boost stalled relations. Ankara hopes to make progress on visa waivers and modernizing the EU-Turkey Customs Union, but Turkish officials say little progress had been made so far.

Erdoğan is also irritated with the state of defense cooperation with Washington. The US suspended Turkey from the F-35 fighter program and blocked it from buying the fifth-generation stealth fighters in 2019, after Turkey purchased the Russian S-400 air-defense system. Ankara wants Washington to lift its ban on the F-35 and recently suggested a new proposal, something US officials are unlikely to accept. Ankara has long been seeking Western cooperation in the nuclear energy sector as well, to no avail.

Erdoğan must think that BRICS membership will help him secure concessions from the West. If that does not work, the Turkish president hopes to get what he needs from fellow BRICS members. Things may not quite work out that way, however — at least not in the short term. Sino-US rivalry and the Russian war against Ukraine may have rejuvenated BRICS, but the bloc is economically stagnant, riven with tensions, and far from articulating an alternative world order, let alone changing it. But most importantly, Ankara’s accession is not a done deal. Russia welcomed Turkey’s decision to formally apply but said a final decision requires a consensus of all current member states. There are diverging opinions within the bloc regarding further expansion. China wants to allow in new actors; but Brazil, India, and South Africa are skeptical, fearing enlargement will strengthen China’s clout in the Global South. Member countries also have differing views toward Erdoğan’s Turkey in particular. China, considered to be the wallet of the bloc, finds Turkey under its current leadership risky when it comes to investing in big infrastructure projects. Moreover, there is competition over regional influence between the Middle Eastern countries that recently joined the bloc on the one hand and Turkey on the other. All these factors suggest Erdoğan may not be able to cash in on his latest foreign policy move quickly enough to fix his domestic problems.

Follow: @gonultol

Photo by Ali Jadallah/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.