Contents:

- US Assistant Secretary Leaf swings through regional hotspots

- Iraq steps away from the brink of civil war

- Pakistan’s floods and the intersection of three crises

- After the recent fighting in Libya, renewed efforts on the political front

- Egypt highlights the urgency — and difficulty — of tackling climate challenges ahead of COP27

- In Israel, the debate over Iran was frozen in "1938"

US Assistant Secretary Leaf swings through regional hotspots

Gerald M. Feierstein

Distinguished Sr. Fellow on U.S. Diplomacy; Director, Arabian Peninsula Affairs

-

The State Department’s top official for MENA is on a two-week tour of the region, visiting Tunisia, Israel and Palestine, Jordan, and Iraq.

-

Assistant Secretary Leaf’s trip included several current hotspots, with an eye toward reasserting U.S. leadership and calming troubled waters.

U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Barbara Leaf’s trip to North Africa and the Middle East, which began on Aug. 29, included several of the current hotspots in her area of responsibility, with an eye toward reasserting U.S. leadership and calming troubled waters.

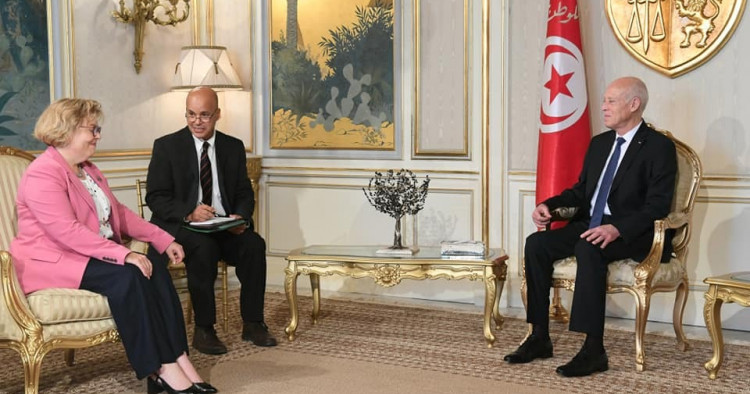

The regional tour kicked off in Tunisia, where, according to the State Department announcement, Leaf planned to engage Tunisian officials and experts on steps needed to improve the political and economic environment in the country as well as to review mutual efforts to address the continued civil conflict in neighboring Libya. But her visit notably came on the heels of Tunisia expressing anger over recent comments by Secretaries Antony Blinken and Lloyd Austin as well as the U.S. ambassadorial nominee for Tunisia, Joey Hood, who collectively flagged Washington’s concerns about the North African state’s drift away from its promise of democratization. The U.S. officials’ remarks were seen as especially critical of the leadership of President Kais Saied.

In Israel and Palestine (Sept. 1-3), Leaf’s visit was aimed at heading off a Palestinian push to become a full member of the United Nations that President Mahmoud Abbas is expected to launch during his travel to New York for the opening of the U.N. General Assembly later in September. The Palestinian effort, which everyone expects to fail, comes in response to their disappointment over the results of President Joe Biden’s July stop in Israel and Palestine, which brought no new U.S. initiatives to change the current dynamics in the relationship between the Israelis and Palestinians. Leaf was expected to press Israel to implement some of the measures it had agreed to during the Biden visit, including easing travel restrictions on Palestinians and allowing the installation of 4G internet infrastructure in the Palestinian territories. But with the Israelis in the midst of another election cycle, the caretaker government will be reluctant to take steps that could complicate its electoral prospects. The announced completion, on Sept. 5, of the Israeli military investigation into the May 11 shooting death of noted Palestinian-American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh is unlikely to improve the atmosphere between the two sides. While Israel acknowledged that she was likely killed by Israeli gunfire, the just-released report termed the shooting “accidental”; whereas, the Palestinians believe Abu Akleh was the victim of a targeted assassination.

After a brief visit to Jordan (Sept. 3-4) to review the implementation of the new, seven-year, $10.15 billion Memorandum of Understanding on Strategic Partnership, Leaf made her last (initially unplanned) stop in Iraq. There, she told the Iraq News Agency that the country’s political situation is “on the verge of collapse.” Her visit follows a telephone call between President Biden and Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi last week, in which the U.S. leader reiterated Washington’s support for the Kadhimi government and a “sovereign and independent Iraq.” Leaf, in turn, stressed the importance of resolving Iraq’s current political confrontation through dialogue and negotiation and emphasized that the U.S. is engaged with all of the Iraqi political parties to encourage dialogue. After her meetings in Baghdad, Leaf traveled to Erbil, where she will remain until the end of the week.

Iraq steps away from the brink of civil war

Randa Slim

Senior Fellow and Director of Conflict Resolution and Track II Dialogues Program

-

After a bout of deadly violence between the forces of Muqtada al-Sadr and the Iran-aligned Coordination Framework, the situation in Baghdad has returned to an uneasy stalemate.

-

Unable to unilaterally impose a solution to the political conflict, the two sides are likely to soon embark on a campaign of mutual assassinations to settle old scores as well as increase the costs to their opponents of continuing with this deadlock.

On Aug. 29, street fights erupted between supporters of Iraqi Shi’a cleric and political leader Muqtada al-Sadr on the one hand and those of the Iran-aligned Coordination Framework (CF) on the other, after Sadr announced his “final withdrawal” from politics and the closure of the majority of Sadrist institutions. He had also declared that he was no longer going to dictate actions for his supporters, who interpreted this as a greenlight to storm Baghdad’s Green Zone, including the presidential palace, the governmental headquarters, and the parliament. They were met with force by militia members of the CF, resulting in a deadly armed confrontation between the two warring factions. Iraqis spent the evening of Aug. 29 thinking the country was heading into an intra-Shi’a civil war.

The following day, Sadr held a press conference during which he distanced himself from the violence and called on his supporters to withdraw immediately from the Green Zone, which they promptly did. Sadr’s decision to step back from the brink of war was mainly prompted by an intervention from Iraqi Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani’s office. There is now an implicit understanding among Iraqi leaders to keep things relatively calm until Arba’een, on Sept. 16, when millions of Shi’a from around the world will partake in a ziyara (pilgrimage), traveling 50 miles between the holy cities of Najaf and Karbala.

The sectarian violence in Iraq attracted the attention of the United States. On Aug. 31, U.S. President Joe Biden telephoned Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi, calling on all Iraqi parties to resort to dialogue to resolve their differences. This was followed by a Sept. 5 visit to Baghdad and Erbil by Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs Barbara Leaf, who conveyed the same message. How much this sudden surge of U.S. interest can influence the political trajectory on the ground in Iraq is uncertain. This is primarily defined by local actors’ cost-benefit calculi and is not easily shaped by outside interventions, especially by the U.S., which has been, politically speaking, missing in action in Iraq.

Iran also sought to intercede by trying to strip Sadr of his religious legitimacy through an intervention by Grand Ayatollah Kazim al-Haeri, who harshly criticized Sadr’s actions. Tehran’s maximalist aim in Iraq remains trying to ensure a united Shi’a front. However, Sadr’s “rebellion” has been a challenge that Iran is finding difficult to contain.

Meanwhile, Prime Minister al-Kadhimi has already convened two dialogue sessions that were attended by the president, the speaker of parliament, and the leaders of the major political factions; but Sadr boycotted both meetings. Still, the participants agreed to form a technical committee that would establish a roadmap on holding early elections (a Sadrist demand) and to formulate proposals on electoral law reforms (as called for by the CF).

For now, the political climate in Iraq remains tense, with both competing sides ready to again resort to arms. They each view this conflict in existential zero-sum terms and think their side has won the latest confrontation. Both are now stuck in a stalemate, however, where neither side is able to unilaterally impose a solution to the political conflict. Going forward, the post-Arba’een period will likely witness a campaign of mutual assassinations to settle old scores as well as increase the costs to their opponents of continuing with this deadlock.

The above is an excerpt from a longer piece that will be published later this week.

Follow on Twitter: @rmslim

Pakistan’s floods and the intersection of three crises

Marvin G. Weinbaum

Director, Afghanistan and Pakistan Studies

-

The deadly floods hit a Pakistani economy under duress, with accelerating inflation, a record-high trade deficit, and a collapsing rupee.

-

Meanwhile, former Prime Minister Khan’s populist campaign to reclaim power and the government’s crackdowns on his supporters undermine the unity needed to deal with the economic and humanitarian crises.

With Pakistan on the verge of bankruptcy, there was understandably a sense of relief when, in July, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) signaled its approval to release $1.17 billion from an existing $6 billion loan program, which, in turn, could unlock additional funds from other international agencies. But just as Pakistan’s shaky ruling coalition seemed to have surmounted one crisis, another was brewing. Late June saw the beginning of unusually early monsoon rains, which have now inundated much of the country and taken more than 1,200 lives. Both crises have intersected with an ongoing struggle among the country’s politicians that could undermine national stability.

Pakistan’s environmental-cum-humanitarian crisis gives little indication it will abate soon. Forecasters predict heavy rains continuing well into September. Even then, the surge of downstream Indus River waters, intensified by rapidly melting glaciers, will linger for some time. The floods hit a Pakistani economy under duress: consumer prices have accelerated above 27%, there is a record-high trade deficit, and the rupee has hit historic lows against the dollar. These developments are occurring in the midst of an ongoing political storm generated by former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s strident populist campaign to reclaim power along with government media crackdowns and arrests of Khan’s allies — all of which seem to be leading to a political showdown requiring military intercession.

The three ongoing crises converge in numerous ways. Owing to the floods, an already low national GDP growth rate will take a severe hit as economic activity slows. Valued agricultural exports will dwindle. More than 45% of the country’s cropland, mainly in Sindh Province, has reportedly been washed away, and costly food imports will be required to keep the population fed. The country will be forced to take on new debt. Initial estimates have placed the price tag for flood reconstruction and rehabilitation at more than $10 billion. Reportedly, the government is weighing returning to the IMF for an emergency loan.

Shehbaz Sharif’s government is feeling the heat politically for agreeing to the IMF’s loan conditions, which necessitated raising domestic oil prices and reducing subsidies. Consumers are reeling from spiking food and electricity costs. The previous Khan government, which had acknowledged the need for negotiations with the IMF, has of course lost no time criticizing the Sharif government for agreeing to the IMF’s strict terms. Even though the ill-preparedness to mitigate the flood damage is the result of decades of poor planning and water mismanagement practices, the overwhelmed current regime stands to bear the brunt of the blame for its grossly insufficient relief efforts. Predictably, the opposition cannot resist politicizing the government’s response to the disaster. In place of the unity needed to deal with Pakistan’s twin humanitarian and economic crises, confrontational politics goes on as usual.

Malavika Radhakrishnan, a research assistant to Marvin G. Weinbaum, assisted with this article.

Follow on Twitter: @mgweinbaum

After the recent fighting in Libya, renewed efforts on the political front

William Lawrence

Non-Resident Scholar

-

A fragile calm has returned to the capital, and the recent deadly violence has helped to refocus attention on the importance of peace and the political process.

-

After nearly a year of discord, the U.N. Security Council finally named a new special envoy, Senegalese diplomat Abdoulaye Bathily.

After Libya experienced its worst fighting in two years in late August, the first week of September has been dedicated to renewed attempts to bring the two sides together to try to forge an agreement for political cooperation and new elections. The most intense violence, during Aug. 27-28, resulted in 42 deaths, including 4 civilians, and at least 159 injured, as militias rained heavy weapons down on civilian areas in and around the capital. There was also dangerous fighting on coastal roads approaching the capital and near two migrant detention centers, involving 560 people. For the third time this year, militias linked to eastern Gen. Khalifa Hifter and the mostly eastern-backed Prime Minister-designate Fathi Bashagha attempted to seize the capital by force and oust the U.N.- and western-backed Prime Minister Abdel Hamid Dbeibah. Each attack has been a show of force that ultimately failed, due in large part to the “deal with the devil” that the previously popular PM-designate Bashagha made with Tripoli’s tormenter, Hifter, to try to return to power.

But a fragile calm has returned to the capital, and the recent deadly violence has helped to refocus attention on the importance of peace and the political process. On the positive side, it was significant that half of the 5+5 Joint Military Commission representing the formal eastern military agreed not to join the battles in Tripoli. The national ceasefire since 2020 formally held. The 5+5 also made progress on a plan for a joint operations room and an agreement on modalities for the withdrawal of foreign forces. Oil production has crept back toward pre-war levels with the ending of pro-eastern blockades. Furthermore, after nearly a year of discord and dysfunction at the U.N. Security Council, and notwithstanding the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Council finally named a new special envoy, Senegalese diplomat Abdoulaye Bathily. Libya’s western government objected to this nomination because Bathily is considered too close to France and their one-time eastern ally Gen. Hifter; but the fact that the divided Security Council could even come to consensus on an envoy was a small triumph for international diplomacy. Meanwhile, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan managed to convoke both rival Libyan prime ministers on the same day to Istanbul to talk peace, stability, and elections. If the national ceasefire and militia ceasefire in the capital can hold, new elements are in place that can lead to progress on the political front.

Follow on Twitter: @WillLawrence111

Egypt highlights the urgency — and difficulty — of tackling climate challenges ahead of COP27

Mirette F. Mabrouk

Senior Fellow and Founding Director of the Egypt program

-

Foreign Minister Shoukry has used his platform as COP27 president to reiterate that the developing world needs help coping with a crisis for which it bears little responsibility.

-

As the host of COP27, Egypt now finds itself in a position where its domestic policies must reflect its international stance.

At the G20 Environment and Climate Ministerial Meeting in Bali last week, Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry was polite but firm. The developed world had to pull its socks up as far as taking responsibility for climate change and helping the rest of the world deal with its impending challenges.

Shoukry is the president of the 27th Conference of the Parties (COP27) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which Egypt is hosting this coming November in the Red Sea resort of Sharm el-Sheikh. Increasingly, he has used his platform to reiterate what has become a familiar theme in his messaging: The developing world needs help coping with a crisis for which it bears little responsibility. A few days earlier, he spoke at Africa Climate Week, where he noted that “Africa is obliged with its financial means and scant level of support to spend around 2-3 percent per annum to adapt to these [climate change] impacts, a disproportionate responsibility that cannot be described as anything other than climate injustice.” His position reflected that of all developing nations: Any action on climate change mitigation and adaption should be guided by the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC) as laid out by the UNFCCC. That principle acknowledges that individual countries have varying capabilities and, just as importantly, differing responsibilities, in addressing climate change. In Bali, he pointed out that the financing promised in Glasgow during COP26 for climate change action has yet to materialize. More disturbingly, the current global economic downturn — a result of fallout from the pandemic and compounded by the war in Ukraine — meant that not only were financial pledges being held up, but the ongoing energy crunch meant dirtier fuels like coal had made a reappearance.

Shoukry noted that, per estimates from the UNFCCC Standing Finance Committee, the developing world will need up to a staggering $11 trillion to deal with climate change challenges — a goal that, so far, does not look imminently achievable. According to the World Economic Forum, not only is global climate change funding insufficient, it is also extremely unevenly distributed, with Africa, for example, receiving less than 5.5% of funds. This is partly down to the global economic downturn but also due to the fact that current financing models simply are not up to the task, with significantly more innovative — and collaborative — financing models needed.

Egypt appears conscious of its role as this year’s standard bearer. The country is scrambling to carry out a raft of domestic environmental campaigns under the Go Green initiative, launched in 2019, aiming to educate people on the importance of preserving the country’s natural resources. Educating citizens may be essential but the government itself appears to be attempting to tread a very fine line between conservation and development. It recently announced an initiative to plant 100 million new trees, even as it faces accusations of razing green spaces for new construction, and has also launched initiatives to protect nature reserves and preserve biodiversity and marine habitats while attempting to tackle potential coastal erosion resulting from development.

It is quite a challenge. While Egypt had already been aware of the need for these initiatives, its timetable has been accelerated. As the host of COP27, it now finds itself in a position where its domestic policies must reflect its international stance. Its environmental house needs to be in order. Egyptian organizers have said that the goal for COP27 is to move beyond the pledges to implementation and financing. As one organizer put it, “The world no longer has time for the more-talk-than-action model.” The same can be said for the host nation.

Follow on Twitter: @mmabrouk

In Israel, the debate over Iran was frozen in “1938”

Eran Etzion

Non-Resident Scholar

-

There is virtually no difference between the main contenders in the Israeli elections when it comes to Iran, including their opposition to renewing the nuclear deal.

-

In Israeli discourse on Iran, the politicians blame each other, the security establishment seeks to rationalize the debate, while the population is focused on domestic challenges.

Iran has been a central issue in Israeli politics and national security policies for the past 30 years. In the 1990s, the late prime minister and pre-eminent national security authority Yitzhak Rabin called for “closing the circle of peace around Israel, before Iran closes its nuclear fuel cycle”; but he was assassinated in the midst of that effort. His successor, Benjamin Netanyahu, positioned himself as a counterterrorism and counter-Iran hawk, which brought him enormous political dividends throughout his 15-year tenure as head of government (1996-1999, 2009-2021), the longest in the country’s history. His famous line uttered in 2006 — “the year is 1938, and Iran is Germany” — continues to cast a shadow over the Iran debate.

Now, in 2022, Israel is gearing up for yet another Netanyahu-driven election cycle, the fifth in three years, and Iran remains at the center of Israel’s national security strategy. Politically, however, Netanyahu’s policies have essentially became a consensus position. There is virtually no difference between the main contenders when it comes to any Iran-related issues, including their stance vis-à-vis the renewal of the Iran nuclear deal, the so-called Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Netanyahu’s simplistic catch phrase, “we are against a BAD deal, but we are not against a GOOD deal,” was whole-heartedly endorsed by his political adversaries — Naftali Bennet, Yair Lapid, Benny Gantz, and Avigdor Lieberman, who, at one point or another, all served as ministers in his national security cabinets. The only remaining political debate is a blame game regarding the relative level of national military preparedness in anticipation of a military “strike” on Iran.

Putting aside the fact that this characterization is a misleading euphemism for a regional war of choice, no political figure has presented even a shred of an alternative strategy. As is often the case on Iran-related issues, Israel’s professional national security establishment is effectively forced to “come to the rescue” of the public policy and democratic debate. Thus, the media is filled with “senior defense/intelligence officials” trying to explain the harsh strategic realities to the Israeli public but also to their political masters: Israel simply has no better course of action than a renewed JCPOA. A “military option” does not currently exist and almost certainly will not in the coming few years. Netanyahu’s anti-JCPOA doctrine failed miserably. “Maximum pressure” resulted in maximum Iranian nuclear enrichment and minimum “breakout time” to a potential nuclear military capability. Moreover, the crucial strategic relationship with the United States was badly damaged in the process; Bennet, Lapid, and Gantz are now invested in trying to repair it.

Under Netanyahu, Mossad, the Israeli intelligence service, became something of a “prime minister’s pet” organization, and it performed incredibly daring and successful sabotage operations against Iran’s nuclear project. Now, the head of Mossad, David Barnea, has notably positioned himself at the most hawkish end of the internal and public debate. On Sunday, he arrived in Washington to try to dissuade the Biden administration from its nuclear talks with Iran. In contrast, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and most of the country’s professional policy community see no better option than a renewed JCPOA that would come with an arms “compensation package” to Israel.

Zooming out, there are three distinct prongs to the Israeli discourse on Iran. The politicians blame one another; the national security echelon desperately tries to rationalize the debate; while the Israeli public is tired of these 30-year-old dynamics. Israelis are mired in more mundane day-to-day issues, including skyrocketing prices and yet another national election centered on Netanyahu’s political and legal future, which again threatens to endanger the foundations of Israeli democracy. Many former national security figures are increasingly adopting the view that the most clear and present danger to Israel is not an Iranian nuclear capability or any other Iran-related threat but rather the possible crumbling of Israel’s democratic system of government and the rule of law. So in that sense, for Israel’s domestic situation, the year might as well be 1938.

Follow on Twitter: @eranetzion

Photo by Tunisian Presidency/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.