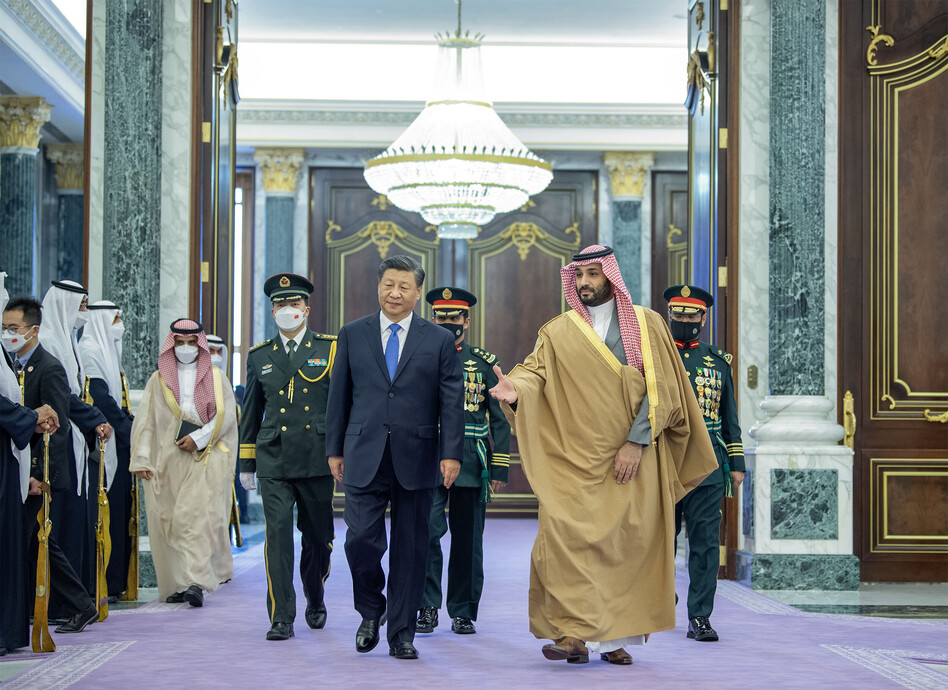

Xi Jinping’s visit to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia this week has attracted worldwide interest — occurring as it does amid China’s expanding ties with MENA countries, the regional states’ more assertive and independent foreign policy postures, strained relations between Washington and Riyadh, and US-China great power competition.

How does increased Chinese engagement across the GCC fit into Beijing’s grand strategy, and what do the Gulf states hope to gain from this relationship? Where are the opportunities and greatest challenges for both sides when it comes to pursuing cooperation in areas as diverse as energy, transit, AI, telecommunications, and tourism? And how does all that affect the U.S. policy approach toward this complicated yet geostrategically vital region?

The Middle East Institute is pleased to convene two expert panels and a keynote speech responding to these questions and more. Please join us for this half-day conference analyzing increased China-GCC relations and locating the U.S. policy response in a shifting geopolitical arena.

Conference Agenda

10:00am - 11:00am EST | Panel: Understanding China-GCC Engagement & the U.S. Policy Response

Sun Degang

Professor of Political Science, Institute of International Studies, Director of Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Fudan University

Chas Freeman

Chair, Projects International Inc.; former U.S. diplomat

Andrea Ghiselli

Assistant Professor, School of International Relations and Public Affairs, Fudan University

Grant Rumley

Goldberger Fellow, Washington Institute for Near East Policy

Jonathan Fulton, moderator

Assistant Professor of Political Science, Zayed University

11:00am - 11:30am EST | Keynote: Daniel Benaim, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Arabian Peninsula Affairs, Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs, U.S. Department of State

Event Summary

Jonathan Fulton

China’s approach, contrary to what many in the United States believe, is not new. This is exemplified by different strategies the Chinese are taking. In reality, these Summits have been ongoing, but of course, calling it the “First Summit” gets lots of press in Western tabloids. For many China hawks, this title proves to be extremely misleading. There is not a large Geopolitical shift occurring here. Xi Jinping's recent trip should not be compared to President Joe Biden’s July 2022 visit to the region. It should be compared to Donald Trump’s. Xi’s trip represents a similar stage in relations to when President Trump touched down in Riyadh.

On the other hand, U.S. messaging toward the region is not working. Washington has failed to implement meaningful and guided policy since the end of the Cold War. As a result, they need to figure out a better way to articulate why China poses a threat to these Gulf States. Funding Israel blindly and without repercussions won’t help America’s case.

Sun Degang

Great power competition is indeed shifting. China is making active efforts to bring the Arab world into closer relationships built with trade, cooperation, and investment in mind. This is exemplified through China’s recent China-Arab Summit, their bilateral China-GCC Summit, and their joint China-Saudi Summit. The GCC states are moving from the West’s camp to autonomy. They sense they are able to play off of this competition for the betterment of their own states. It is important to note, however, that the GCC states are still fundamentally entrenched in the U.S.’s security blanket. While Russia cooperates with the GCC through OPEC+, India, Japan, and South Korea have also become strong trade partners in the region.

From our perspective, the why China question is simple. We have a large and dynamic population, we have the capacity to build vast amounts of infrastructure quickly, we have the largest export-based market in the world, and we have an imagined community with the people of the Gulf who have a shared history of colonization. Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) member states share the belief that sovereignty is more important than human rights. This GCC and SCO partnership represent a, “back to history,” mentality. It is also important to note that all of the mentioned summits were held in the Gulf, not Washington or Beijing. This is representative of the power dynamics at play here.

Chas Freeman

Washington has faltered greatly in both its China policy and its Middle East policy. China is offering pragmatic diplomacy with no strings attached to all of these GCC countries. On the flip side, Washington is always asking GCC members to ignore its negligence for Israel’s increasingly racist practices toward Palestinians, as well as asking these states to put aside their own aspirations and follow through with our political demands. The U.S.’s only counter is always that they share a mutual enemy in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Before the end of the Cold War, strong relations with the GCC states made sense, as the U.S. was the largest oil customer; now, it has the world’s second-largest oil reserves and is one of the world’s largest exporters (the Gulf’s greatest competitor).

Arab opinion on China has never been higher, while, at the same time, Arab opinion on the U.S. remains incredibly low. China is well-positioned to go on a security offensive when it chooses to. China maintains good relations with the GCC states but remains incredibly cautious as all parties recognize the U.S.’s dominant security position in the region. Even with this in mind, GCC populations still see the U.S. as their greatest threat. China is keenly aware that the U.S. subsidizes Israel (to the detriment of its relations with Arab states) and accuses the U.S. of maintaining rampant Islamophobia. At the same time, the GCC populations turn a blind eye to the CCP’s treatment of Muslim Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

The Middle East is still the most politically unstable region in the world. China still relies on the U.S. Navy to secure access to MENA resources and trade networks. Yet China has also begun to conduct regional naval exercises on its own. A base in Djibouti and a larger trade network have alerted U.S. security practitioners. To defeat this new rival, the U.S. must raise savings rates and return to exporting, rediscover non-military aspects to statecraft, and adopt more generous tech policies. Sadly, the likelihood that we are able to climb out of this hole is very low.

Grant Rumley

There is an extreme disconnect between how people in the region view our competition with China and how we view our competition with China. At the moment what is occurring in the Middle East is not in fact competition. China has a clear edge in the economics sector, while the U.S. remains the region’s security hegemony. Currently, the U.S. is unaligned with its partners in MENA. At the same time, there is a much more concerted effort underway for Arab states to buy from China. However, many of the Arab states do not see an issue with buying from both the U.S. and China. In their minds, “they can have their cake and eat it too.” For the U.S., there is a ceiling. It behooves us to clearly lay out with our partners where our red lines are. We need to leverage arms sales and intelligence sharing against their decisions to buy Chinese drones and host military bases. Co-development, co-production, and co-R&D with China can be encouraged, but military and security should still be leveraged

Andrea Ghiselli

The U.S. needs to keep in mind the probability of a Chinese reaction to any policy shake-ups (and what that reaction could be). If Ambassador Freeman is correct in the continued reaction of Arab states toward U.S. policy, then China can continue on its unflappable trajectory. It is also important to consider whether China’s goal is actually the middle ground, not to push the U.S. away completely but to simply gain a stronger foothold and force the GCC states to be more autonomous or more ambiguous in their policy. Local actors such as the Saudis might try to overemphasize Chinese actions; they would like to paint a picture that China supports them instead of their rivals.

Daniel Benaim

America’s relationship with the Gulf continues onward. It is clear to us that the trajectories of the Gulf and the U.S. remained intertwined. There are five lead policy directives that we are following. The first is to strengthen our partnerships with the Gulf states. The U.S. cannot rest on its laurels. There are simply too many areas in which our Gulf partners can provide us with a mutually beneficial relationship. The second is defense and deterrence cooperation. The U.S. backs this commitment up with the tens of thousands of troops it has stationed across the region. Third is de-escalation and the desire to lower tensions and end conflicts wherever possible. Fourth is regional integration. The Middle East is the least integrated region in the world, and building inter-regional cooperation is crucial for its future success. Lastly, the U.S. will always promote human rights as enshrined in the Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations.

When it comes to security, there is a depth of history and past that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) cannot match and is not trying to. Meanwhile, as PRC trade has grown to $300 billion within the region, U.S. trade has only grown to $100 billion. This is in part due to China’s insatiable hunger for Middle Eastern oil. As a result, the current situation between the Gulf and the PRC needs a thoughtful approach from the U.S. We need to remain attuned to trends. It needs to be made clear that we are committed to managing our relations with GCC partners responsibly. The U.S. must be more explicit about what it is asking for and what it isn't asking for from its partners. We need to give countries the right to decide for themselves where and whom they should partner with. We should continue to leverage those relationships properly.

On the other hand, China cannot continue to subject coercive deals on these countries that have no way of expecting their debt trap diplomacy. It remains true that cooperation with China in certain sensitive areas can jeopardize U.S. technology and security. The PRC’s engagement in the region is not solely economic, contrary to what they project. Their data harvesting and intelligence gathering makes it difficult for other countries to work with our military and chips away at existing security relationships.

There must be a viable alternative. The U.S. will continue to counter the PRC’s angles on Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Xinjiang. These diplomatic efforts continue to move the needle in the right direction, and the U.S. will continue to protect these countries against bullying and aggression. As President Biden says, “Don't compare me to the almighty, compare me to the alternative.” The U.S. may falter in its policy implementation, but its goal remains the promotion of freedom and prosperity in the Middle East. China does not share that goal. The most advantageous strategy the U.S. can pursue is to play to its own strengths. We must show up as an engaged partner, think creatively, and continue to show that our approach does deliver for both the people and governments in the region.

Photo by Royal Court of Saudi Arabia/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images