On a sub-level inside one of the Smithsonian’s art galleries in Washington, a man stood entranced by the Golden Hour, a six by eight foot photographic composition of Mecca.

The man noted the dozens of cranes and the Makkah Royal Clock Tower, a monstrous and controversial piece of architecture that dwarfs everything around it. Then, with his finger, the visitor carefully air circumnavigated around the Great Mosque.

“What’s this tiny black cube in the middle?” he asked, pointing to the Kaaba.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then the Golden Hour is the ultimate commentary on what is happening to Islam’s holiest site. And it hardly seems to matter that the observer knew nothing about Islam or Mecca, like the visitor at the Smithsonian, who explained that he was a high school art teacher from New York with a background in construction and neon light installation. The scenario unfolding in the photograph delivers the story regardless.

Such is the boldness of the work of Ahmed Mater, whose exhibit is the first solo show at a major U.S. museum by a Saudi national. Born and raised in southern Saudi Arabia, just north of the Yemeni border, Mater is part of a silent but sizable middle class, growing up without the birth privileges and ostentatious wealth associated with the kingdom. He trained as a medical doctor before teaching himself painting and photography—he even taught himself how to build a sophisticated camera by watching videos on YouTube.

Mater shot Golden Hour from atop a crane with a Sinar 8x10 inch camera that he assembled, and 15 minutes of exposure, timed at the moment of sunset. The dramatic scene captures Mecca as it hangs in the twilight, slightly closer to darkness than to light.

“I think I chose this angle because for me it’s like a theatrical scene for all the change,” he said in a private interview during his U.S. tour, where his exhibit Symbolic Cities is currently on display at the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery until September 18. Golden Hour is part of a series called the Desert of Pharan, the biblical place that in the Islamic tradition refers to Hijaz, which spreads south from Jordan and the Sinai to include Mecca. Tradition holds this area was home to Abraham.

Antenna, Ahmed Mater

Antenna, Ahmed Mater

“I call it the Divine Comedy of the change happening in our time. When you see it as a video, and you hear the chink and clang of construction, it’s like you’re in a theatre, and then you hear the Azan,” said Mater, referring to the call to prayer.

Mater faces so many challenges as an artist in Saudi Arabia that it is difficult to identify them all. For one, the kingdom offers no formal training programs in the arts. Any schoolchild can tell you that depicting living things in a drawing or a photograph is forbidden, though it is never clear why ubiquitous photos of the king are allowed. Then there is the strict segregation of space along many lines; male and female, private and public, white collar and blue collar, indigenous and expat. Mater explained that all of these red lines end up both defining and inspiring his art.

“I think the Wahhabi restrictions shaped our art and how it has hidden messages behind messages, which gives us a lot of power,” he said.

It is against this backdrop of restrictions that Nature Morte, another one of Mater’s color photographs in the Desert of Phares series, offers commentary on the appropriation of space. Shot from a luxury hotel room inside the Makkah Royal Clock Tower—this particular room charges $3,000 per night—an empty, red velvet chaise sits next to a bowl of fruit overlooking a window that frames a tiny, black cubical Kaaba with the pilgrims performing their Tawaf below. Tawaf is the theological term that describes the hajj ritual during which Muslims circumambulate the Kaaba seven times, moving counter clockwise, and wearing simple cloth to shed all signs of material wealth.

So, to what extent is private space encroaching upon these public holy spaces in Mecca? And is public space during the season of humility turning into a commodity of luxury?

“The answer is in the photos,” Mater said, sheepishly.

Anyone familiar with the construction craze in Saudi Arabia and its Gulf neighbors might be inclined to lament the obsession with building the world’s tallest building (currently Burj Khalifa in Dubai, but in December the kingdom announced it will build a taller one that reaches 1km in height), or biggest shopping mall or whatever multibillion-dollar glitzy project that polarizes observers either into applauding the stupendous effort or shaking their head over yet another eye sore.

The Makkah Royal Clock Tower is no exception. It boasts the world’s largest clock face and third tallest building, soon to be joined by a 10,000-room mega-hotel, expected to be the largest in the world. As with most everything in Mecca, the Royal Clock Tower is enshrined in religious taboo.

The $20 billion project to expand the pilgrimage area began in 2011 in an effort to accommodate more pilgrims during hajj season in Mecca.

So when voices of dissent began to rise over the building of the Makkah Royal Clock Tower, which broke ground in 2004, they were quickly drowned out with reminders that the Servant of the Holy Mosque and King of Saudi Arabia was only trying to expand the site to accommodate more pilgrims. Who could possibly be against that?

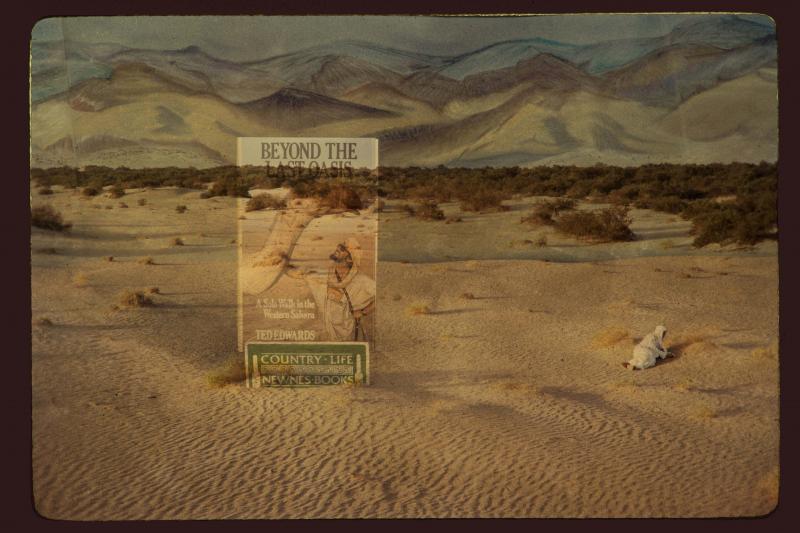

Beyond the Last Oaisis, Ahmed Mater

Beyond the Last Oaisis, Ahmed Mater

Mater’s rising stardom and the international accolades that his work is earning has landed him in the good graces of the kingdom’s authorities, who proudly feature his photographs in local media. Mater’s friend turned promoter, Stephen Stapleton, himself an artist from Britain and one of Mater’s co-founders of Edge of Arabia, a U.K.-based nonprofit art consortium, best articulates the under-the-radar subversiveness of Mater’s work.

“I see his work featured in the Arab media, but I can’t read Arabic, so it looks like an infiltration,” he said, standing next to Mater during one of the many presentations of Mater’s work in Washington circles.

Though grateful for all of this success, Mater says a dark cloud hangs over his accomplishments. Among his close friends and circle of artists, one creative mind is missing. He is Ashraf Fayadh, the Palestinian poet detained last year in Saudi Arabia and condemned to death for apostasy. International pressure convinced the Saudi authorities to overturn the sentence in favor of an eight year prison term and 800 lashes.

“Yes, I’m happy for my exhibit opening, but my happiness is not complete because one of my friends is in jail,” he said.

Yet with two-thirds of the country’s population under 30, social change seems a given. The kingdom boasts one of the highest rates of social media use in the world, an outlet that Saudi youth are exploiting to create new connections and a creative economy that transcends the usual restrictions. Indeed, the main art scene in Saudi Arabia today thrives underground, with private exhibits shown among networks of artists and admirers who often meet online. Some are starting to move offline, forming studios that offer a rare intellectual and creative space to congregate. Mater and his wife, Arwa al-Neami, an artist in her own right, have opened such a studio and already credit it with an intense exchange of ideas.

Asked what he sees for the future of his country and its artists, Mater said he’s cautious but hopeful.

“We are full of nervous optimism about the potential of this real movement,” he said. “That a new generation of artists are working on the very edge of their society, and outside of the international cultural conversation have risen to this challenge, is an inspiring and important development.”

Images courtesy of the artist

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.