In reaction to the Oct. 7 Hamas attack on Israel and the subsequent Gaza war, the Biden administration articulated a short list of objectives to support its ally, protect civilians, prevent the conflict from spreading, and end the fighting. A year later, the Biden administration has been unable to achieve nearly any of its stated diplomatic and security outcomes. America’s lack of strategic focus and will to take actions aimed at fundamentally shifting the dynamics in the region, a condition that predated the Biden administration, has incentivized regional actors to turn toward violence rather than choose a diplomatic path.

The following report assesses the US government’s success and failures in meeting its goals over the past three months. It represents the independent analytical judgments of one scholar at the Middle East Institute based on his policy research, with research support and independent feedback from colleagues in a peer review process.

Introduction

The United States is trapped in a reactive Middle East policy approach of its own making one year into a regional war that continues to expand.

This strategic drift in US policy is a direct result of the Biden administration’s wishful thinking and unwillingness to exert leverage through diplomacy backed by a coherent regional security approach. As a result, the United States has been unable to achieve nearly any of its stated diplomatic and security outcomes. America’s lack of strategic focus and will to take actions aimed at fundamentally shifting the dynamics in the region, a condition that predated the Biden administration, has incentivized regional actors to turn toward violence rather than choose a diplomatic path.

The main drivers of events in recent months are countries like Israel and Iran and groups like Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis. The Biden administration has found it difficult to deal with the challenges posed by these actors, many of whom are at odds with long-term US strategic goals in the region.

A larger group of countries, including a number of key US partners, are not direct combatants in the wars, but they are directly affected by the past year’s events. These states, including Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Egypt, Jordan, and Turkey, have tried to navigate the regional strategic tensions but have been unable to put forward a collective diplomatic approach capable of changing the trajectory toward more conflict. Years of self-deterrence and mixed signals from multiple administrations in the United States have motivated some key regional partners to engage in strategic hedging and actions that make diplomacy and peace more elusive.

Since the war began, the Biden administration has been guided by six main objectives, in order of importance as defined by US officials in word and deed:

-

Support Israel’s self-defense and objective of eliminating the threat posed by Hamas;

-

Secure the safe return of hostages;

-

Prevent a wider regional war;

-

Protect civilians caught in the crossfire;

-

Respond to a growing humanitarian crisis in Gaza; and

-

Create a post-war plan for reconstruction leading to a two-state solution and wider regional normalization efforts in coordination with regional and international partners.

This report is the fourth in a series of analyses attempting to clinically analyze US policy in the Middle East that have included thus far:

-

An initial assessment of President Joe Biden’s approach to the Middle East from 2021 to 2023, released in September 2023: Treading Cautiously on Shifting Sands: An Assessment of Biden’s Middle East Policy Approach, 2021-2023 | Middle East Institute (mei.edu)

-

An assessment of Biden’s Middle East approach six months into the Gaza war, released in April 2024: The Biden Administration’s Middle East Policy at a Time of War: An Assessment of US Policy Six Months Into the Israel-Hamas War | Middle East Institute (mei.edu)

-

An analysis of how the Biden administration handled the war from April to July 2024, released in July 2024: The Limits of Biden’s Middle East Diplomacy: An Assessment of US Policy, April-July 2024 | Middle East Institute (mei.edu)

During the past three months, the two top priorities of the Biden administration’s Middle East policy have been 1) securing a cease-fire and hostage-release deal between Israel and Hamas and 2) preventing a wider regional war. On both of these priorities, the Biden administration has not achieved its aims, though US security support and quiet diplomacy very likely prevented even worse outcomes from unfolding.

Supporting Israel’s Self-Defense

-

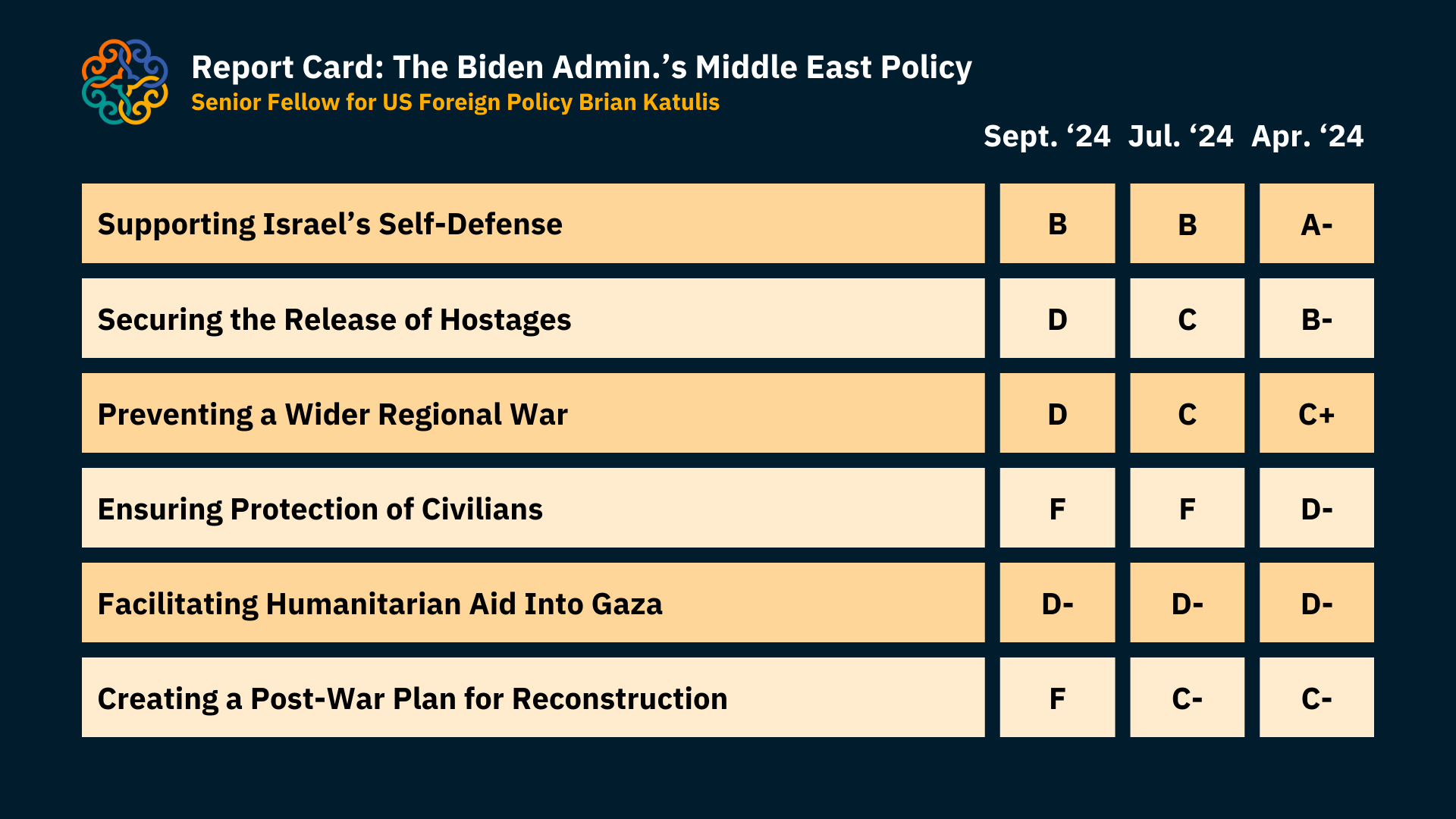

Overall Grade for US Policy: B (Same as B in July, down from A- in April)

-

The Biden administration’s top priority, as demonstrated in word and deed, is to support Israel’s self-defense, and it has done so with few restrictions, even as it raised some of its own concerns and criticisms about Israel’s conduct of the war.

-

Ten months into the war in August, the Biden administration approved $20 billion in weapons and aircraft sales to Israel, even in the face of strong criticisms from some of its regional partners about how Israel was conducting the war against Gaza. It has largely ignored the concerns expressed by some voices in Congress, the American public, and regional partners about this support to Israel, even though it made occasional statements and limited gestures aimed at shaping Israel’s trajectory.

-

Israel has sought to restore a semblance of strategic deterrence against its enemies and adversaries across the region, but it has been unable to do so. It faces a multi-front war of attrition from a mix of state and non-state actors that use asymmetric warfare, cyberattacks, information warfare, and increasingly conventional military attacks.

Securing the Release of Hostages

-

Overall Grade for US Policy: D (Down from C in July and B- in April)

-

The Biden administration has invested months of diplomatic efforts centered on reaching a cease-fire between Israel and Hamas and securing the release of Israeli and American hostages held by Hamas in the Gaza Strip. The last cease-fire to secure a hostage release ended in early December; since then, the United States has worked closely with Qatar and Egypt in fruitless efforts to produce a deal.

-

In the last three months, the Biden administration stepped up its direct diplomatic engagement on seeking to achieve a deal and made a cease-fire and hostage release a top priority, using the three-phase plan President Biden put out in May as the template.

-

President Biden pointedly declared in September that he did not think Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was doing enough to free the hostages and get a cease-fire deal. At the same time, Secretary of State Antony Blinken has publicly pointed the finger at obstructionism by Hamas at various times during trips he has made to the region since Hamas started this war. Diplomacy during an active war between two combatants who do not recognize the others’ legitimacy and see the fight as existential is very challenging.

-

The negotiations over a cease-fire and hostage release became further complicated by the fact that discussions related to long-term security, including control of the border region between the Gaza Strip, Egypt, and Israel and the movement of Palestinians living inside Gaza, were part of the talks.

-

Hamas murdered six hostages it held in Gaza in late August, even as cease-fire and hostage talks were underway. These deaths came about three months after Biden had released his cease-fire plan. Some voices blamed Israel’s current government for the lack of a deal, including protestors in Israel, while others pointed the finger at Hamas.

-

In mid-September, Secretary Blinken made his 10th trip to the Middle East since the start of the war in pursuit of this deal. This trip was overshadowed by growing conflict between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon, including attacks on Hezbollah’s command, control, and communications infrastructure while Blinken was in the region.

-

The Biden team conceded in late September that it was unlikely to secure the release of hostages and achieve a cease-fire in the Gaza war, even though it will continue trying.

Preventing a Wider Regional War

-

Overall Grade for US Policy: D (Down from C in July and C+ in April)

-

The United States continues to play an integral role as the most important external actor in the Middle East when it comes to security and military cooperation. It has an extensive and diverse network of partners across the region, and it has sought to encourage greater security integration and cooperation among them. This unrivaled position has likely prevented the security situation across the region from become worse than it might have been, but the situation remains volatile.

-

The past three months have witnessed an escalation of tensions between Israel and Iran. Israel’s attacks and assassinations of leaders of Hamas and Hezbollah, including a strike that killed Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran on July 31, exactly two months after President Biden publicly issued his Gaza cease-fire proposal, raised the prospect of direct conflict between Israel and Iran once again.

-

Israel’s stepped-up military strikes in Lebanon against Hezbollah throughout September, in reaction to ongoing attacks and threats from Hezbollah, are now in the spotlight. The Israeli strike that killed Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah on Sept. 27 was part of a wider campaign targeting the movement’s leadership, command-and-control structures, and capacities to strike Israeli territory. Lebanon and the broader region remain in a period of deep uncertainty and unpredictability.

-

The Middle East has been teetering on the edge of a wider escalation for much of this past year, with the risk of nation-states going directly to war with one another growing. Since Iran and Israel’s fairly controlled exchange of fire this past April, the two countries have pulled back from the brink of a wider war, instead choosing to engage in tit-for-tat attacks, mostly through Iran’s partners like Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen. Yet the mounting Israeli campaign against Hezbollah, including the killing of Nasrallah, pushed the Iranian regime to respond directly, on Oct. 1, launching hundreds of ballistic missiles at targets across Israel, including Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. Israel immediately promised to retaliate.

-

In addition to this ongoing conflict between Israel and Iran, the region continues to experience threats from the Islamic State in Syria, which has seen a resurgence there and in certain parts of the region and world, as seen in attacks as far flung as Russia, Iran, Oman, and key parts of Africa.

-

Also in the past three months, the Houthis in Yemen continued to pose a threat to international shipping in the Red Sea and conducted limited strikes against Israeli territory. In addition, militias in Iraq and Syria posed a threat to Israeli territory and US troops deployed in the region. Just as Israel has been unable to restore a sense of strategic deterrence, the United States has also struggled to prevent daily waves of attacks coming from various groups linked to Iran.

-

During the past three months, the United States military deployed additional assets across the region. In August, the Pentagon announced it was sending additional warships, combat aircraft, and anti-ballistic missile-defense systems to the Middle East in order to prepare for possible attacks by Iran, Hezbollah, and other Iran-aligned groups in reaction to the killing of leaders from Hezbollah and Hamas in late July. In September, the Biden administration declared that it was sending more forces and equipment to the region amid the escalation between Israel and Hezbollah.

-

The absence of an overarching coherent regional strategic approach by the United States that integrates these military moves and security cooperation efforts has not stopped escalatory trends.

Ensuring Protection of Civilians

-

Overall Grade for US Policy: F (Same grade as F in July, down from D- in April)

-

The Israel-Hamas war in Gaza continues to exact a devastating human toll on Palestinians — the overall death toll in Gaza surpassed 40,000 this summer and continues to rise, while over 90,000 people have been injured.

-

The spotlight was understandably on the Gaza Strip, where the loss of life has been the greatest. But the situation in the West Bank and East Jerusalem has also been volatile. US policy has done very little to shape the trajectory of events in the West Bank. The Biden administration imposed limited and targeted sanctions on violent Israeli settler groups, but these measures do not appear to have stopped the negative trends.

-

As the conflict spreads to Lebanon, concerns about the loss of innocent lives will increase since Israel has already conducted military operations in heavily populated areas and Hezbollah has deeply embedded itself in key areas around Lebanon.

-

The United States offered some public statements but no major policy shifts following the killings of aid workers in the Gaza Strip in Israeli military operations. The Sept. 6 shooting that killed an American citizen, Aysenur Eygi, by the Israel Defense Forces similarly prompted statements but no major policy shifts. US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin expressed “grave concern over the IDF’s responsibility for the unprovoked and unjustified death of an American citizen,” and Secretary of State Blinken called for “fundamental changes” in Israel’s rules of engagement.

Facilitating Humanitarian Aid Into Gaza

-

Overall Grade for US Policy: D- (Same as D- in July and April)

-

The United States continues to play a leading role in efforts to deliver humanitarian aid to Palestinians in the war-torn Gaza Strip; yet the sum total of those efforts is still woefully insufficient.

-

In the past three months, limited pauses in fighting were negotiated in order to distribute a polio vaccine this summer after the disease reemerged in the Gaza Strip. The outbreak was due in large part to the destruction of health and sanitation facilities in the war and the resulting water insecurity and spread of open sewage.

-

The amount of aid that has been delivered is not meeting demand. For a variety of reasons, particularly because of continued fighting, the number of trucks crossing into Gaza to deliver food and aid is only a fraction of what it was before the war began, about 20% of the pre-war level, according to the United Nations’ senior humanitarian and reconstruction coordinator for Gaza. Bureaus inside of the US Department of State and US Agency for International Development warned that Israel was blocking aid and food deliveries, a charge that Israel disputed and resulted in no significant US policy shift.

-

The lack of a clear post-war plan by Israel, the United States, and the broader international community hampers the ability to create a sustainable strategy for aid delivery.

Creating a Plan for Post-War Reconstruction

-

Overall Grade: F (Down from C- in July and April)

-

The Biden administration episodically presented ideas for the post-war situation in the Gaza Strip, and it sent top officials to coordinate with regional partners throughout this period. But there has been no sustained effort that brings together the collective resources and plans, in part because the Biden administration has been engaged in reactive crisis diplomacy.

-

Because the Biden administration’s plan for the region was dependent on achieving a Gaza cease-fire, it has been unable to unlock the potential of its wider plans for promoting greater regional integration in concepts such as the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), a Saudi-Israel normalization deal, or the stated goal of a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

-

The Biden administration outlined a plan in May that sought to link the efforts to resolve the immediate conflict resolution challenges with a long-term plan for Gaza’s reconstruction, in addition to wider efforts to foster increased regional integration. But the long-term planning and diplomatic efforts remain in their nascent stages, as the crisis diplomacy focused on achieving a cease-fire and hostage release has understandably been the higher priority.

Recommendations for the Future Based on Lessons Learned From a Year of War

The 2023-2024 Middle East war and the Biden administration’s Middle East policy approach during this past year offer important lessons for future US policymakers at the operational, tactical, and strategic levels. As with recent US experiences in the post-9/11 wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the United States may lack the capacity to fully absorb “big picture” lessons that should set the country on a new strategic course.

US policy efforts in the Middle East have not been a top focus in America’s 2024 elections, and the nature of the debate in political campaigns and in Congress often does not lend itself to deep insights.

Here are five recommendations for future US policymakers as they consider the challenges ahead for the Middle East.

1. Make clear why the Middle East matters for overall US national security strategy.

One of the reasons why the Biden administration’s approach to the Middle East has seemed flailing, reactive, and at times rudderless and impotent is that Biden’s team came into office lacking a clear rationale for why America should engage in the Middle East. In the administration’s first year, senior Biden officials spoke about how it was important to go “back to basics” and not do too much in the region. But this mindset contributed to the Middle East challenges the Biden team is now facing as it leaves office, because it was not prepared with a strategic case for why the United States should engage with the region. US policy toward the Middle East remains mostly disconnected from a wider national security strategy, and the administration suffers from significant bandwidth challenges in advancing its overall national security approach. One key reason why the Biden administration has found itself in this reactive, crisis-management position is that for more than a decade, voices have been calling on successive US administrations, both Democratic and Republican, to reduce American engagement in the Middle East. As a result, US policy has become less consistent and strategically reliable than it was in the past.

Today’s international system is unlike the one that emerged in 1991, after the end of the Cold War. The broader Middle East’s role and relevance in that global context continues to shift. For decades, many in the United States have viewed the Middle East as an “arc of crisis” that did little more than export problems and security threats. For three main reasons, the Middle East has gained new relevance for Americans: security, economics, and values.

-

Security: Protecting America, its worldwide allies, and its regional partners against terrorist threats originating in the Middle East — such as al-Qaeda, the Islamic State group, and Iranian terrorist and proxy networks — should remain a focus of US engagement in the region.

-

Economics: The Middle East has become an economic hub in its own right, serving as an important transit point for people and cargo moving by air and sea — as well as an area of geopolitical competition with Russia and China. The Middle East’s energy resources remain critical to the global economy — particularly for American allies in Asia, such as Japan and South Korea.

-

Values: More than 13 years after the start of the popular uprisings across the region, the Middle East remains on the front lines of the worldwide struggle for human dignity and universal rights, values that the United States supports — including religious freedom, women’s rights, and freedom of expression. The region’s lack of freedoms prevents its people from realizing their aspirations of dignity and prosperity while undermining its stability in the long term. In a global context where Chinese and Russian technological authoritarianism and state-dominated capitalism presents itself as an alternative model of governance, the Middle East is a contested space in this global competition over values.

One key challenge America faces in advancing a strategic approach to the Middle East is the complications presented by domestic politics and the different voices advocating competing agendas for US policy in the Middle East. US presidents and their administrations need to listen to the many different voices seeking to shape policy; but ultimately, a successful strategy depends on blending the right policy tools to produce the outcomes that advance American interests and values, something that no recent US administration has gotten right in the Middle East.

2. Define specific and realistic outcomes US policy seeks to achieve, rather than creating a policy framework that is centered on what it does not want to see happen.

The next US administration should articulate an agenda that is more proactive than reactive to events, and it should seek to marshal a diplomatic and security approach that makes America’s adversaries respond to the actions of America and its partners, not the other way around. The Biden administration came into office making the goal of ending the post-9/11 wars a top agenda item, and America’s military withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 marked the end of an era in US foreign policy. But it also made a distinct impression among adversaries and partners in the region and around the world.

3. Address the short-term crises in ways that take steps toward achieving the long-term goals.

The Biden administration had an agenda for the future that centered on rebuilding relationships in Asia and Europe, connecting America’s economic revival and national industrial policies with partners in those regions of the world, and addressing global challenges like climate change. In the Obama administration, some officials called this focusing on the “long game.” But as the Obama administration saw in Syria, the ISIS crisis, and other challenges, if the short-term crises aren’t sufficiently addressed, then there are no clear pathways to produce sustainable outcomes in any “long games” that are envisioned.

Deeply rooted regional crises need to be addressed at their roots and not through superficial, short-term fixes that don’t address the challenges that have plagued the region for years. Encouraging regional economic integration without advancing a two-state solution that results in Palestinians having a sovereign state will not likely stabilize the region and will more likely accelerate the gap between the rich and poor. Similarly, state-backed militancy and terrorism are a core challenge in the Middle East, but long-term visions that do not have a short-term plan for addressing the destabilizing impact of current conflicts will never get fully off of the ground.

4. Set a new framework for collective action and working more closely with regional partners in the Middle East.

The United States needs reliable partnerships to get big things done in the world, including and especially in the Middle East. About midway through his presidency, President Biden seemed to recognize this and articulated the value of those partnerships on his trip to the Middle East on July 13-16, 2022. A key objective for this multi-country visit was to send a signal that the United States remains committed to the region at a time of geopolitical uncertainty when other outside actors, particularly Russia and China, are working in their own ways to impact regional trends.

This was a much different message to the leaders of key countries in the Middle East that was at odds with much of what Presidents Donald Trump and Barack Obama had said, both of whom emphasized pulling back from the region. Yet the Biden administration did not fully develop a proactive strategy, even if it had one in the works by 2023; and then events in the region knocked it off balance and away from its long-term agenda items, including an Israeli-Saudi normalization deal, the IMEC concept launched at the G-20 summit in India, and other distant-horizon ventures aimed at advancing regional integration.

5. Advance a new regional strategy that seeks to create a State of Palestine and addresses the role that Iran and its network of partners play in undermining regional and global security.

The next US administration and future leaders should keep in mind two core drivers of these events: a regime in Iran that operates with a revolutionary ideology that seeks to upend the state order of the Middle East, and an increasingly right-wing Israeli government that rejects a two-state solution, even though there is a historic opportunity to open relations with key Arab states if it took steps to define a clear end to this war that leads to a State of Palestine. Extremist voices and retrograde movements in the region that reject efforts to forge peace have a symbiotic relationship with each other — hardliners in Iran in many ways feed off of the hardline views projected by those on the extreme right in Israel.

Conclusion

For nearly a decade and a half, the debate within the United States about its role in the wider Middle East has swung back and forth, between but also within subsequent US administrations. The Biden administration experienced some major operational bandwidth challenges in its national security apparatus. Combined with a lack of strategic focus and clear priorities in its overall foreign policy, this could hamper America’s ability to advance a more engaged strategy across the broader Middle East. Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine and China’s actions in Asia and around the world will continue to take up much time and attention, too.

The basic impulse of the Biden administration to avoid adopting a more proactive stance in its diplomatic and military approaches across the Middle East, driven in part by the bandwidth constraints, has prolonged conflicts like that between Israel and Hamas, which has been metastasizing into a regional Middle East war. It could also close off opportunities in the short run for advancing some of the more proactive engagement steps the Biden administration was pursuing before Oct. 7. The wider Middle East region still hangs on the precipice of a deep abyss as the war grinds on, simultaneously adding to broader geopolitical uncertainties in Europe and Asia. The current crisis will likely shape and define America’s relationship with the region for years to come.

The Biden administration made some of the same mistakes previous US administrations have made on other foreign policy issues: trying to do too many things at once without putting enough resources into the overall effort in order to achieve success. But the next administration can learn from the past few years to hopefully avoid the same pitfalls.

Brian Katulis is Senior Fellow for US Foreign Policy and Senior Advisor to the President of the Middle East Institute.

Photo at the top: US President Joe Biden speaks in the South Court Auditorium at the White House, in Washington, DC, on Tuesday, Sept. 3, 2024. Photograph by Kent Nishimura/Bloomberg via Getty Images.

Acknowledgments

This report represents the independent analytical judgments of one scholar, based on his policy research and feedback from colleagues and peers, with essential research support from Athena Masthoff.

The author would like to thank colleagues and peers who took time to review a draft of this report and offer comments, including Matthew Czekaj, Khaled Elgindy, Nimrod Goren, Charles Lister, Paul Salem, Elliott Sanders, Susan Saxton, Zeina Al-Shaib, Alistair Taylor, Marvin G. Weinbaum, and Rebekah Wharton.