It is said that Egypt is the Pyramid and the Nile

But they forget that true Egyptians

When the right time comes

Are able to do the impossible

—Hamza Namira, “El-Midan” (“The Square”)[1]

On February 7, 2011 Wael Ghonim spoke at length with Mona el-Shazly on her popular nightly talk show on Egypt’s Mustaqbal Television Network, al-Ashira Masa’an (“ten at night”). For the previous eleven days, the young Google executive and tech-savvy leader of the protests that had started on January 25, 2011 had been blindfolded and held in a secret prison by Egyptian security forces. His emotional and tearful answers to el-Shazly’s questions provided much-needed energy to the demonstrations that would topple Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak. In a poignant moment, Ghonim revealed that he had coped with the despair and hopelessness of his detention by silently singing “Ehlam Ma’aya” [“Dream With Me”] by Hamza Namira, a young Egyptian singer. Namira had become a fixture at Tahrir Square and the unofficial “fannan at-thawra” [“Artist of the Revolution”].[2]

U.S. policy makers rarely pay attention to singers — even a singer as important as Namira, who is favorably compared to the father of Egyptian popular music, Sayyid Darwish (1882–1923). There is little question that cell phones and social media allowed Ghonim and other young activists to organize Egyptians hungry for political change online. But Namira’s music also played a vital role. He not only inspired Ghonim and millions like him to believe that a better future was possible, but also inspired them to take collective action and to make that future a reality.

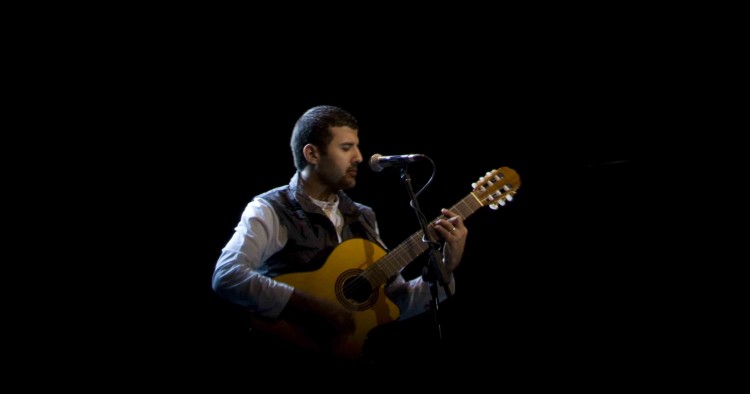

Namira’s path to stardom preceded the events of the Arab Spring by many years. He was born in Saudi Arabia in 1980, where his father, an Egyptian Muslim, worked as a doctor and an amateur musician. Although Namira received private music lessons as a boy, he was not seriously interested in music until he was in his teens. At the time, living in Egypt, he learned how to play the guitar, the keyboard, and the oud (a pear-shaped traditional Arab instrument similar to the guitar). He also developed interests in several musical styles: Middle Eastern, Egyptian traditional and folk music, light rock, jazz, and Latin music. From 1999 until 2004, Namira played in a band headed by the Alexandrian artist Nabil Bakly and went on to form his own group. Additionally, Namira studied accounting at the University of Alexandria.[3] He hoped that the degree would allow him to earn a large enough independent income to pursue his musical career without fear that he would have to one day choose between earning a living and compromising his values.[4]

Through a series of mutual friends, Namira met with executives of the British-based record label Awakening Records in 2004.[5] The record label had already launched Sami Yousef’s career and was looking for singers who could similarly address the growing demand in the Muslim World and beyond for music that is inspired by faith and driven by values.[6] Awakening also devotes enormous resources to developing its new artists and to producing high-quality music videos;[7] Its March 15, 2012 video for Maher Zain — “Number One for Me” — is nearly six minutes long and is accessible in 17 languages, including Chinese, Bangladeshi, Russian, and Urdu.[8]

In 2007, Awakening Records signed Namira and a year later it released his debut album, Dream with Me. The album soon reached the top ten of Virgin Megastore’s List in Egypt and was popular among Egyptian college students and young professionals. These groups embraced Namira’s criticisms of society and government as well as the caustic humor in his songs, all of which are sung in Egyptian colloquial Arabic. Equally compelling was the singer’s sincerity and his personal commitment to his art and to upholding its values. Two of the album’s songs would play a key role in the Arab Spring.

The first, “Dream with Me,” is an uplifting song that promises that a better future is possible and that all people can fulfill their dreams if they work together. Throughout the song, Namira plays a guitar and repeats:

Dream with me

Tomorrow’s coming

And if it doesn’t come

We will bring it ourselves….

All our steps will lead us to our dream.

No matter how many times we fall

We can always get up

We can break through the darkness

We can turn our night into a thousand days.[9]

Significantly, while the official video for the song (produced by Awakening Records) chronicles the attempts of a boy growing up in a poor seaside village to build a boat and leave home, many Egyptians saw the song as an allegory for their own dreams to metaphorically or literally escape the “darkness” of contemporary Egypt and its political and social constraints. As of March 2012, the official video has gotten over 900,000 hits on YouTube.[10]

The political and social themes in “Dream with Me” are even more evident in the second song, “Ya Tair” (“O Bird”), an Arabic folk song set to drums and several other traditional Arab instruments. The song’s subject is an “imprisoned bird” who wishes to fly away “till things get better” — an image that many young Egyptians could easily identify with.[11] Namira calls on the bird to “sow a few seeds” that will “grow in the heart of the free.”[12] In the chorus, he predicts that the seeds will grow from twenty to two hundred to millions and millions. In a passage that virtually foreshadows the events in Tahrir Square in January 2011, Namira says:

Oh my broken heart

Don’t spend all your life mourning

You might not be a great leader

But you have millions of people behind you

If your seeds grow

Salah al-Din might rise[13]

The final line’s reference to the rise of the 12th century general and statesman Salah al-Din (Saladin) is especially important. He is seen by Egyptians and other Arabs as a great hero, who presided over an unparalleled era of national vitality. By referring to Salah al-Din’s rise, Namira is not promising that the seeds will bring the famous general back to life. Instead, he is suggesting that they will bring about a historic period of reform and revival in which Egyptians will regain the national greatness that they possessed in previous eras.

After the release of his first album, Namira regularly performed to sold-out audiences, which included large numbers of both Christians and Muslims (Egyptian Copts are some of his biggest fans).[14] Among the most significant of these performances was one at the American University in Cairo in March 2010 with Maher Zain and Mesut Kurtis, singers who had also signed with Awakening Records and have become superstars in their own right.[15] Namira opened the show with a new song, “Ya Israel” [“Oh Israel”). The emotionally-charged song voices his defiance and bottled-up anger (and that of millions of other ordinary Egyptians) at Israel and its failure to respect Palestinians and other Arabs. When Namira tearfully completed the song by asserting that the voice of the song is that of Egypt addressing Israel, the crowd roared its approval.[16] Following the show, a female Egyptian professional told the English-language daily newspaper The Cairo Daily that she loved “the revolutionary feel” of Namira and Zain's music, who were the “future of the young pop culture of music.”[17] In her eyes, their work was not “the usual empty lyrics” heard on television “or the classic religious sermons that are not in touch with the new generation.”[18]

In the months after the concert, technical and political forces would catapult Namira to the center of Egyptian national life. In the years after the release of Dream With Me, Facebook and other social media use increased markedly in Egypt thanks to the introduction of cell phones and especially smart phones, which expanded access to the internet. Facebook use in Egypt alone rose from 800,000 users in 2008 to over 4.7 million in December 2010.[19] The process was aided in March 2009 when Facebook launched an official Arabic version of the website.[20] Overall internet penetration grew in Egypt from 4% in 2004 to over 24% in December 2010.[21]

The June 6, 2010 death of Khaled Said in police custody, an internet activist who had posted a video of police officers dividing the spoils of a drug bust, galvanized the online community, especially Wael Ghonim. That month he anonymously founded a special Facebook page to bring Khaled’s killers to justice, “Kulluna Khaled Said” [“we are all Khaled Said”]. The page worked in tandem with Arabic and English sites and eventually grew to 400,000 followers.[22]

Ghonim quickly learned that facts and statistics produced mass outrage and a sense of community online in Egypt, Tunisia, and the wider Arab world, where there was a “deep common anger.”[23] But it was harder to convince people to voice their outrage in the streets. Ghonim addressed this problem by creating a new video that combined a series of images of the first protests linked to Said set to the words of “The Resurrection of the Egyptians,” an Egyptian nationalistic song. The results were electrifying:

More than 50,000 members of the page watched the video in the next few days. People found the fusion of images, lyrics, and music inspiring and moving. It was different from the regular practice of lawyers and human rights defenders, who used facts and statistics to garner support. Instead, the video created an emotional bond between the cause and the target audience. Clearly both are needed.[24]

An important psychological bond had been forged. Members on the page “expressed their desire” to participate in new demonstrations, “especially after seeing the images and video.”[25] The subsequent public events were hugely successful: both the number of participants and the locations of events increased significantly.[26] It was now clear that a music video could motivate individuals online to take mass collective action.

But the deepest significance of this link and what Namira would later term “the ‘real’ effect of music”[27] did not become clear until December 2010 when the “deep anger” that Ghonim witnessed online exploded into popular protests in Tunisia. The spark was the video of the self-immolation of Tarek Muhammad Bouazizi, a young Tunisian, which spread rapidly online and was later shown on Al-Jazeera’s Mubashar television.

While Ghonim initially resisted any discussion of the events in Tunisia on “Kulluna Khaled Said,”[28] Tunisian President Zine El-‘Abidine Ben ‘Ali’s infamous speech on January 13, 2011 and his decision the next day to resign and flee to Saudi Arabia “changed everything.”[29] Before Ben Ali’s departure, Ghonim could not believe that an Arab leader would yield to the demands of a peaceful revolution.[30] For the first time, he felt free to criticize Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak in public and to imagine that it was possible to topple his government. A groundswell of support emerged to turn protests on January 25, 2011 — ironically National Police Day — into a massive rally against the Egyptian president at Tahrir Square. Namira was one of a number of Egyptian celebrities to publicly back the event,[31] and Ghonim attached a link to “Dream with Me” to his final post on “Kulluna Khaled Said” on the night of January 24, 2011, the day before the rally. In his recently-published memoir, Revolution 2.0, Ghonim writes that he hoped that the song would be “a call to everyone to dream of a better tomorrow that we would share in making.”[32]

Although Egyptian security forces arrested Ghonim on January 25 and prevented him from returning to Tahrir Square for 12 days, his use of “Dream with Me” succeeded in its mission. Millions of Egyptians responded to his call to dream of a better tomorrow, including Namira himself, who often attended the protests in Tahrir Square with his family and performed for the crowds there. His songs, which embodied the values and the reality of the protests, were “all over the square.”[33] In an interview after the revolution with Insight magazine, Namira spoke at length about his experiences in Tahrir and his astonishment that the “seeds” he had spoken of in “O Bird” had blossomed in 2011 — decades before he could have possibly hoped that they would. In Namira’s eyes, “that was the best thing about the Egyptian Revolution.”[34]

In the months following President Mubarak’s resignation, Namira emerged as a major public figure. Awakening Records released Namira’s second album, Insan [Human], to great fanfare in July 2011. It has 16 songs that touch on issues as diverse as ethnic relations, hypocrisy, the poor state of Egyptian education, and immigration. While the album is mainly traditional Egyptian pop music with lyrics in Egyptian colloquial Arabic, there are also a host of musical styles that reflect Namria’s eclectic background and interests. Three songs on Insan are inspired by rock, one is inspired by jazz, and another incorporates funk, disco, and dance music.[35]

In the title song, a passionate vocal, Namira reveals his desire to realize the ideal human being. Such a person is kind, helps others, loves and does not hate, and has a dream, an aim, and a hope for a better tomorrow. The song’s video implies that such an ideal person exists in every Egyptian. Throughout the video Namira performs while walking through different parts of Egypt and encountering people of different genders, ages, and social backgrounds.[36]

An even more openly patriotic song on Insan is his extended ballad dealing with the 2011 protests at Tahrir Square, “El-Midan” [“The Square”]. In the song, which opens with a moving melodic piano and violin akin to a national anthem and then breaks into a high-spirited song, Namira repeatedly tells his listeners to “Raise your head because you are Egyptian.” He is referring to their work at Tahrir Square.[37] In the song’s emotional highpoint, he asserts that Egyptians are capable of anything that they set their minds to do:

It is said that Egypt is the Pyramid and the Nile

But they forget that true Egyptians

When the right time comes

Are able to do the impossible[38]

With such soaring lyrics, “El-Midan” and “Insan” became hit songs and Namira’s record sales rose to the top of the Virgin Megastore charts in Egypt and surpassed those of the Arab World’s most popular contemporary singer, Amr Diab.[39] As of March 2012, Awakening Records’ official video for “Insan” had logged over 1.8 million hits on YouTube. In a sign of Namira’s growing global appeal, the song is available in Arabic, English, French, Malaysian, and Turkish.[40]

The whole of Egyptian society (and the world) has taken note of Namira’s fame. His Twitter engagement is one of the highest in Egypt, breaking the top ten most popular accounts in the country. When British Prime Minister David Cameron visited Egypt on February 21, 2011 (only ten days after Mubarak left office), Namira was one of a select group of people invited to meet with him and to participate in a one-hour discussion about the future of Egypt.[41] Namira’s help was sought (and granted) for Egyptian anti-smoking campaigns and for programs to teach music to disabled children. Every candidate for the nation’s presidency sought his endorsement. While Namira has refused to endorse a candidate, he offered to perform at campaign rallies. Even major multinational companies such Vodafone have asked Namira to endorse their products.[42]

As American analysts and scholars work to better understand Egypt and the wider Arab world in the 21st century, they would be well advised to pay close attention to the lyrics of Hamza Namira and other artists whose words embody the aspirations of millions of individuals in the Middle East. Namira is especially important for two reasons. First, his success demonstrates the importance of music (especially when tied to images) as a method of convincing online groups that political change is possible and inspiring them to take collective action. Not only do we see this in Egypt and the Arab world, but also recently in North America with intense activism tied to the YouTube film Kony2012.[43] Second, although Namira is a Muslim, his vision, unlike that of Maher Zain, is nationalistic and secular. His songs and social commentaries have resonated among diverse sectors of the nation’s increasingly fractured post-revolutionary society. While searching for solutions to their nation’s daunting economic and political challenges in the coming years, Egyptians may increasingly turn to the words of an artist who reminds them of a time and place when they were united, dreamed of a better future, and were able to do the impossible.

[1]Hamza Namira, “El-Midan,” Insan © Awakening Records, July 12, 2011. Unless otherwise noted, all translations are by the author. The author thanks Ahmed Jeddeeni with his help with writing this article.

[2]Sameh Ibrahim, “Hamza Namira: A Dream Come True,” (In) Sight Magazine, Vol. 16, No. 3 (April 14, 2011), http://egypt-insight.com/?p=234. For the video clip of the interview with Wael Ghonim with English subtitles, see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SjimpQPQDuU.

[3]Biographical information drawn from http://www.awakening.org/hamzanamira/1_home/index.htm and http://www.facebook.com/7amzanamira?sk=info.

[4]Ibrahim, “Hamza Namira.”

[5]Ibrahim, “Hamza Namira.”

[6]Interview by the author with Sharif Banna, CEO Awakening Worldwide, December 23, 2011; and E-mail correspondence between the author and Sharif Banna, CEO Awakening Worldwide, March 15, 2012.

[7]Interview by the author with Wassim Malak, Co-founder of Awakening Records, November 18, 2011.

[9]Hamza Namira, “Ehlam Ma’aya,” Ehlam Ma’aya© Awakening Records, January 15, 2009.

[11]Hamza Namira, “Ya Tair,” Ehlam Ma’aya© Awakening Records, January 15, 2009. E-mail correspondence between the author and Sharif Banna, CEO Awakening Worldwide, March 17, 2012. The author thanks Sharif Banna for providing him with Awakening Records’ official English-language translation of the song.

[12]Namira, “Ya Tair.”

[13]Namira, “Ya Tair.”

[14]E-mail correspondence between the author and Sharif Banna, CEO Awakening Worldwide, March 15, 2012.

[15]Zain is a Swede of Lebanese origin, while Kurtis is a Macedonian of Turkish heritage. For more on Maher Zain, see Sean Foley, “Maher Zain’s Hip But Pious Soundtrack to the Arab Spring,” The Atlantic, August 10, 2011, http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2011/08/maher-zains-hi…; and Sean Foley, “Maher Zain, Technological Change, and Southeast Asia’s Role in the Modernization of the Muslim world,” Focus On Essay: Oxford University Press Islamic Studies Online, January 2012, http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/Public/focus.html#1009-con-note9.

[16]For a video clip of Namira singing at the AUC concert and the crowd’s extended reaction, see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QRMO5mYxFkA. The song was subsequently released as part of the 2011 album Insan under the title “Esmy Masr (Live)” [“I am Egypt”].

[17]Donya Abdulhadi, “Fans throng to Maher Zain's Album debut concert at AUC,” The Daily News New Egypt, March 26, 2010.

[18]Abdulhadi, “Fans throng to Maher Zain's Album debut concert at AUC.”

[19]Statistics on Facebook use in Egypt are drawn from Fadaia Salam and Racha Mourtada, “Facebook Usage: Factors and Analysis,” Dubai School of Government: Arab Social Media Report, Vol. 1, No. 1 (January 2011), p. 5, http://www.dsg.ae/en/publication/Description.aspx?PubID=223&PrimenuID=1…; and http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/612/egypts-revolution-2.0_the-face….

[20]Ian Black and Jeremy Kiss, “Facebook Launches Arabic Version,” The Guardian, March 10, 2009, http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2009/mar/10/facebook-launches-arabic-ve….

[21]Salam and Mourtada “Facebook Usage,” p. 12.

[22]Wael Ghonim, Revolution 2.0: The Power of the People is Greater Than the People in Power (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), pp. 58–81.

[23]Ghonim, Revolution 2.0, p. 85.

[24]Ghonim, Revolution 2.0, pp. 86–87.

[25]Ghonim, Revolution 2.0, p. 87.

[26]Ghonim, Revolution 2.0, p. 94.

[27]Ibrahim, “Hamza Namira.”

[28]Ghonim, Revolution 2.0, p. 131. Ghonim remembers in his memoirs that he insisted that the co-manager of the Kullena Khaled Said Facebook Page, Abdel Rahman Mansour, take down the first post put on the page about the Tunisian protests and to prohibit further posts. Ghonim thought it was too dangerous to discuss the issue online in Egypt.

[29]Ghonim, Revolution 2.0, p. 131.

[30]Ghonim, Revolution 2.0.

[31]Ghonim, Revolution 2.0, p. 173.

[32]Ghonim, Revolution 2.0, p. 174.

[33]Ibrahim, “Hamza Namira.”

[34]Ibrahim, “Hamza Namira.”

[35]Bassem Abou Arab, “Hamza Namira: Insan,” Cairo 360: The Definitive Guide to Living in the Capital, August 1, 2011, http://www.cairo360.com/article/music/2383/hamza-namira-insan/.

[37]Namira, “El-Midan.”

[38]Namira, “El-Midan.”

[39]E-mail correspondence between the author and Sharif Banna, CEO Awakening Worldwide, March 15, 2012.

[41]E-mail correspondence between the author and Sharif Banna, CEO Awakening Worldwide, March 15, 2012; Nicholas Watt, “David Cameron Arrives in Egypt to Meet With Military Rulers,” The Guardian, February 21, 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2011/feb/21/david-cameron-visits-egy….

[42]Interview by the author with Sharif Banna, CEO Awakening Worldwide, December 23, 2011.

[43]For more on Kony2012, see Roger Cohen, “#StopKONYNow,” The New York Times, March 13, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/13/opinion/cohen-stop-kony-now.html?_r=1….

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.