This article is part of MEI's series on the Biden Transition

As the U.S. prepares to head to the polls to choose its next president, Iran finds itself at a dead end. Hit hard by American sanctions and its own mismanagement of the economy, Tehran needs to negotiate with Washington to get out of its current economic crisis and shore up its waning popular legitimacy. With an eye to addressing these issues and mindful of the steady erosion of support for the government, President Hassan Rouhani has obtained permission from Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to negotiate with the U.S. While the news has not yet been made public, Rouhani has told Ayatollah Khamenei that he will begin talks to reach an agreement with the winner of the upcoming election — regardless of who it is — and the Iranian leader has given his initial consent.

Such a move would have significant popular support in Iran. The majority of the population agrees that the government should negotiate with the United States. According to a poll by an independent news site, 92 percent of respondents agreed with negotiations. Four percent said they "agree to negotiate, but not with the Trump administration," and the rest, 88 percent, said they would agree to negotiate with the winner of the election, no matter which candidate comes out on top.

Even Ayatollah Khamenei himself seems to realize that something needs to give. Looking at his speeches, despite the regular use of phrases like "resistance to the United States," one can see a clear pattern: Whenever there is a problem in Iranian society, he blames it on a foreign actor, like the United States, Israel, or Western countries in general — as if Iran and its leaders have no agency or ability to address its problems themselves.

Who would the U.S. negotiate with?

The definition of government in Iran is different from that in many other countries: In the Islamic Republic the government and the ruling elite are two separate entities, and it is the ruling elite that holds the real power. Therefore, if the U.S. or other foreign governments want to start a new round of negotiations with Iran, they should look for negotiators who are part of that ruling elite, rather than ones that hold a high-ranking state position. Involving some of the Iranian supreme leader's advisers in the talks — such as Ali Akbar Velayati, the supreme leader's international affairs adviser — could guarantee Iran implements any agreement reached.

Who will negotiate on behalf of the Iranian regime?

Iran’s presidential election is scheduled for next June and there is overwhelming evidence that the next president will be close to the ruling elite, conservative circles, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). If Ayatollah Khamenei wants, he can start secret negotiations with the United States, as he did eight years ago, that last until the end of Rouhani's administration in June 2021, and then sign a new agreement with the U.S. and European countries. However, over the years Ayatollah Khamenei has made it clear that although he is the main decision-maker, it is the government that is responsible for execution — and it alone is subject to the scrutiny of public opinion and bears the consequences of any decisions taken. In other words, Ayatollah Khamenei has all the authority but none of the responsibility. Therefore, he can authorize Rouhani’s government to start negotiations in private, while continuing to defend his anti-American views and ideology in public, making it appear as though the government is looking to negotiate, but not him (or the ruling elite).

Ayatollah Khamenei's gamble

Ayatollah Khamenei’s rule has followed a modified version of the theory put forth by Ibn Khaldun, a 14th-century Arab scholar, of the three stages in the rise and fall of a government: the initial struggle and upheaval, the emergence of dictatorship and tyranny, and finally, aristocratic luxury and corruption. Before the U.S. withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), there were clear signs of authoritarianism and tyranny, financial and administrative corruption, and class divisions in Iranian society. After the U.S. left the JCPOA in May 2018 and reimposed sanctions that November, economic collapse was added to the issues facing the Iranian regime. The assassination of Gen. Qassem Soleimani, head of the IRGC – Quds Force, in Baghdad in early 2020 only heightened the pressure, prompting Iran’s supreme leader to make a high-stakes bet, gambling that Trump would fail to win a second term. Ayatollah Khamenei refused to negotiate with the United States — or rather with Trump specifically — and imposed austerity measures, hoping to buy time so Iran could negotiate with the next U.S. president instead, over a return to the JCPOA.

Therefore, the question of who wins the upcoming U.S. presidential election is even more important for Iranians than the results of their own presidential election in 2021. Indeed, one might even say that out of all countries outside the U.S., the American election has the biggest impact on Iran and its people. Although there are no voting stations for people to participate in the U.S. election in Iran, Iranians are as eager to learn the winner as Americans are themselves. The race between Trump and Joe Biden is so important that some Iranians, in line with Islamic beliefs, have made "vows"1 for the success of their favorite candidate, while others have even gone so far as to compose songs to encourage Americans to vote.

Who do Iranians prefer?

The main causes of Iran's economic crisis are U.S. sanctions, first and foremost, and the regime’s mismanagement, but regardless of who is responsible it is the Iranian people that pay the price. Trump's sweeping sanctions have caused the economy to collapse, resulting in poverty, unemployment, a shrinking middle class, and rising crime. At first glance, one would naturally conclude that the Iranian people are hoping for a Biden victory, but that isn’t necessarily true.

Talking to people in Iran, it is clear that Trump has a lot of supporters among the population too. Although they may be a minority, they believe that Trump's policies have brought the government of the Islamic Republic closer to its end and that a Trump second term might lead to its fall and usher in a positive change in Iran.

Who does the regime prefer?

Ayatollah Khamenei made a high-stakes bet that Trump wouldn’t be re-elected, while the American president has gone all in on the “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran, hoping to force the regime to make concessions. So far, however, it seems that both leaders have lost their bets. The cost of Ayatollah Khamenei’s gamble has been a change in Iran’s political landscape from a desire for reform to an outright revolution. For his part, despite all the pressure, Trump has failed altogether to persuade Iran to come to the negotiating table.

If Trump wins the election, Iran may well be the biggest loser though. It could have started a new round of negotiations with the U.S. in September 2019, during President Rouhani’s trip to New York to attend the U.N. General Assembly. However, Ayatollah Khamenei prevented Rouhani from meeting and negotiating with Trump, a decision that had direct and indirect consequences for the Iranian regime. The November 2019 nationwide protests that killed hundreds of protesters, the assassination of Soleimani in Iraq, the downing of a Ukrainian plane by the IRGC, and the bankruptcy of the Iranian economy are but a few of them.

Four years ago, Ayatollah Khamenei, in his initial comment on Trump's victory in the U.S. presidential election, said, "Unlike some who celebrate the presidency of Donald Trump or some who mourn the result of the U.S. elections, we neither celebrate nor mourn since there is no difference for us and we are not worried." Nevertheless, of all countries outside the U.S., Trump's victory probably had the greatest impact on Iran. It remains to be seen whether Ayatollah Khamenei's gamble on Trump's defeat on Nov. 3 will pay off. But regardless of who wins the U.S. election, this is a bet that Ayatollah Khamenei has already lost as a result of his own decisions and the rift they have created between him and the people of Iran.

Mohammad Hossein Ziya is a strategic consultant and researcher involved in political and social research, election analysis, and social media campaigns. He has been the chief editor of Saham News since 2010 and is a Non-Resident Scholar with MEI's Iran Program. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

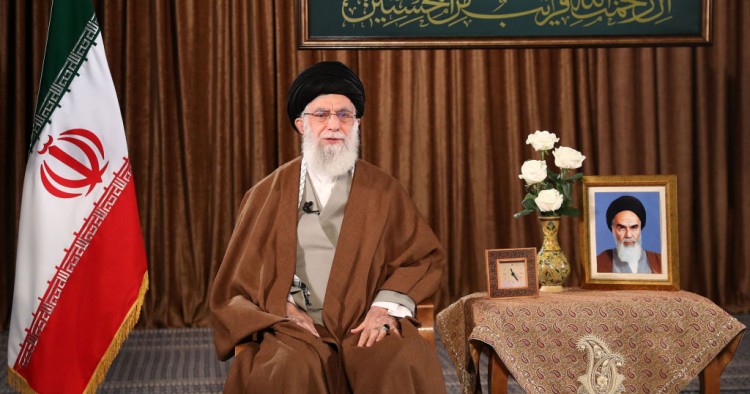

Photo by Iranian Supreme Leader Press Office / Handout/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Endnotes

1 In Iranian folk culture, it is a spiritual contract between God and the person making the vow, to help the needy if the prayer is answered.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.