Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) leader Bafel Talabani is a frequent visitor to Baghdad, traveling to Iraq’s capital an estimated 35 times since the beginning of 2022 or more than once every two weeks on average.

It is indicative of a deliberate strategy by the PUK to increase its activity within Iraq’s federal system, making it a priority, rather than merely an afterthought, to political affairs in the Kurdistan Region. While the PUK has always maintained a presence in federal politics — Talabani’s father, Jalal, was Iraq’s president from 2006 to 2014 and the PUK continues to hold that post — but the younger Talabani is engaged in federal affairs to an unusual degree compared with other Kurdish politicians.

“I like to pop into Baghdad and see my friends regularly,” Talabani told the Iraq Oil Report in an interview in December. “My message to them is the PUK is here to support you, the PUK wants a successful government.”

“[The] PUK historically has made a lot of sacrifices — for Kurdistan, for Iraq — and we're willing to continue doing this,” he added.

Since 2005, the Kurdish parties have kept Baghdad at arm’s-length. They have participated in elections and held ministries, but their political and policy focus has always been centered on the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). However, increasing political and economic dysfunction in the Kurdistan Region has forced a rethink by the PUK, sensing an opportunity to change that calculus by involving itself actively in federal politics.

In many ways, Talabani’s party is facing a serious crisis. It is fractured internally, losing support among voters in its home base of Sulaymaniyah governorate, and playing defense against an increasingly powerful and antagonistic Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), its main rival and the other ruling party in the Kurdistan Region. Its response has been to reach out to allies in Baghdad.1

The PUK’s strategy is a response to two important dynamics. First, relations between Baghdad and the Kurdistan Region have not functioned well over the past decade, soured by disagreements over independent oil sales, the federal budget, Kirkuk and the disputed areas, and the Kurdistan Region’s 2017 independence referendum. This lack of cooperation has hurt the Kurdistan Region financially and blocked progress on legislation like the draft national hydrocarbons law.

“I do not understand the unwillingness to work with Baghdad,” Talabani told the Iraq Oil Report. “Basra is 1,000 times richer than the entirety of Kurdistan. Just Basra. And if the prime minister came to me and said, ‘Hey, Bafel, put your little teapot on this table, and you can be a part of the huge table, including Basra’ — to me, that sounds like a bloody good deal.”

This desire to work with Baghdad is hardly a secret either. Talabani made similar points in a widely-watched television interview with Rudaw in November and told a conference in Erbil on March 1 that he believes that “we could serve the people of the Kurdistan Region through Baghdad.”

The second dynamic relates to political tension between the PUK and the KDP, which is determined to do away with what it views as an artificial political balance between the two ruling parties and cement its position as the dominant power in the Kurdistan Region. This antagonism from Erbil has left the PUK looking for allies and it has apparently found them in Baghdad.

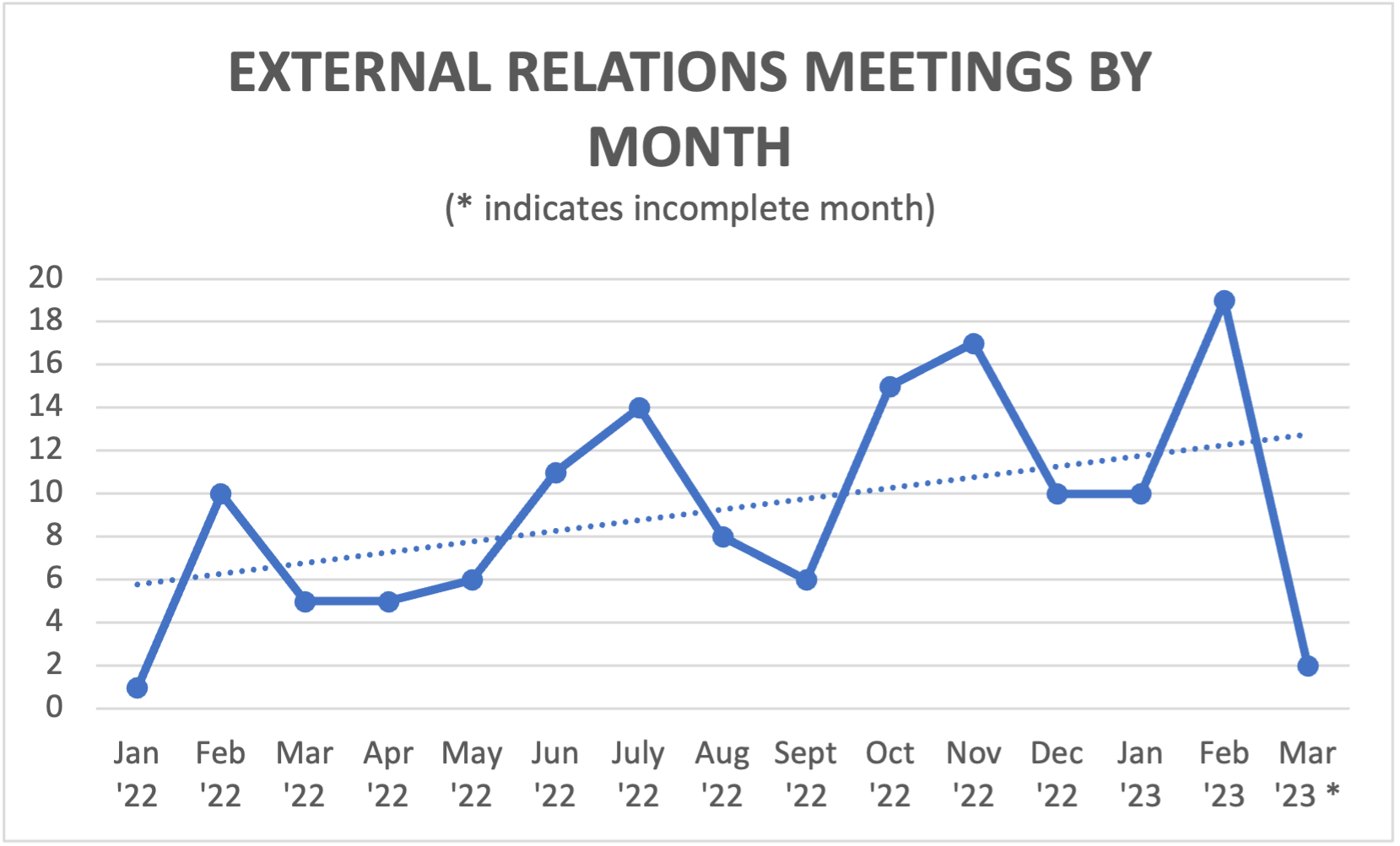

To explore how this strategy is put into practice, I used social media posts from Talabani’s official Instagram account to create a dataset of all of his “external relations” meetings between Jan. 1, 2022 and March 8, 2023. This yielded a catalogue of 139 publicly acknowledged meetings involving at least 75 principals.2

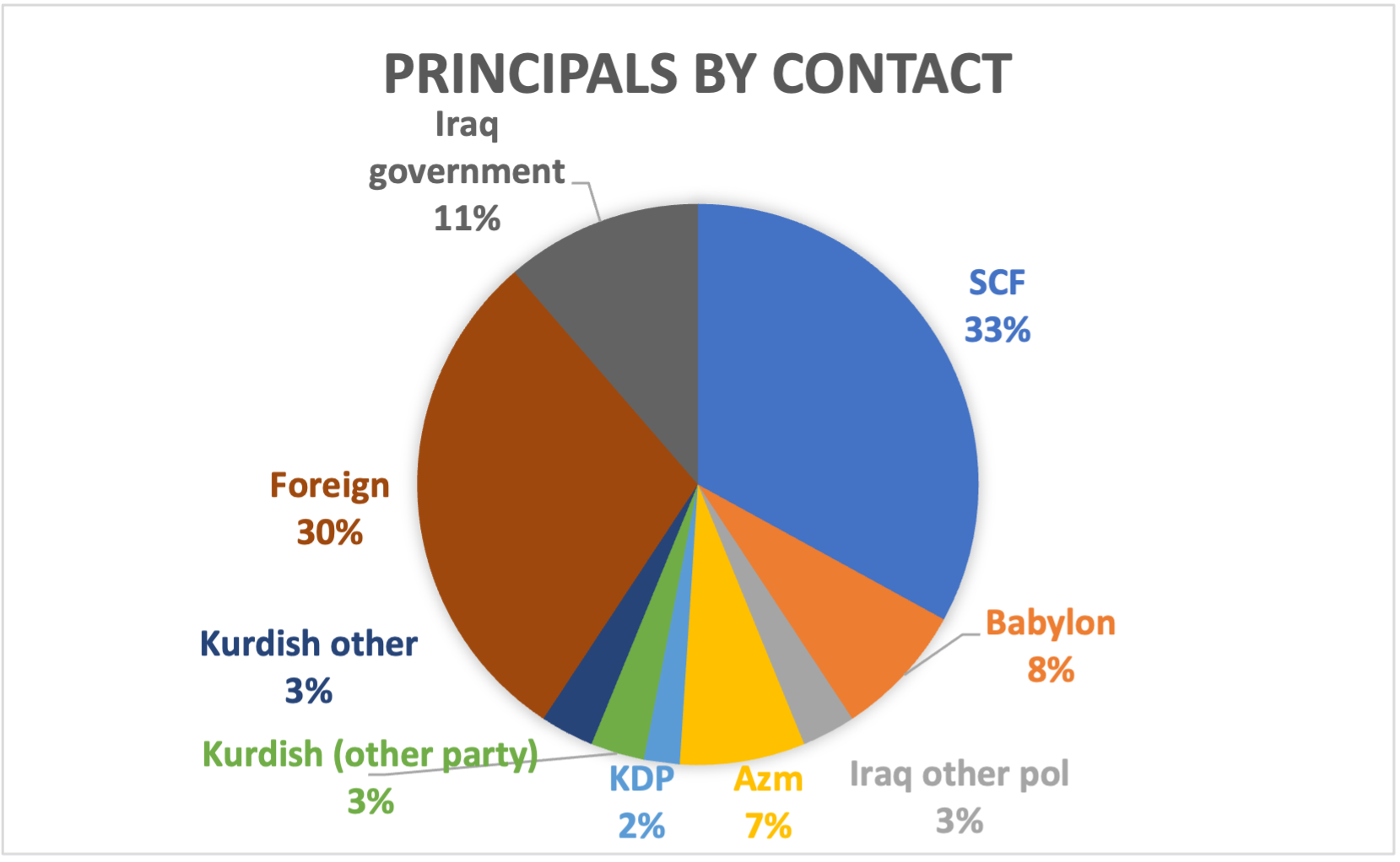

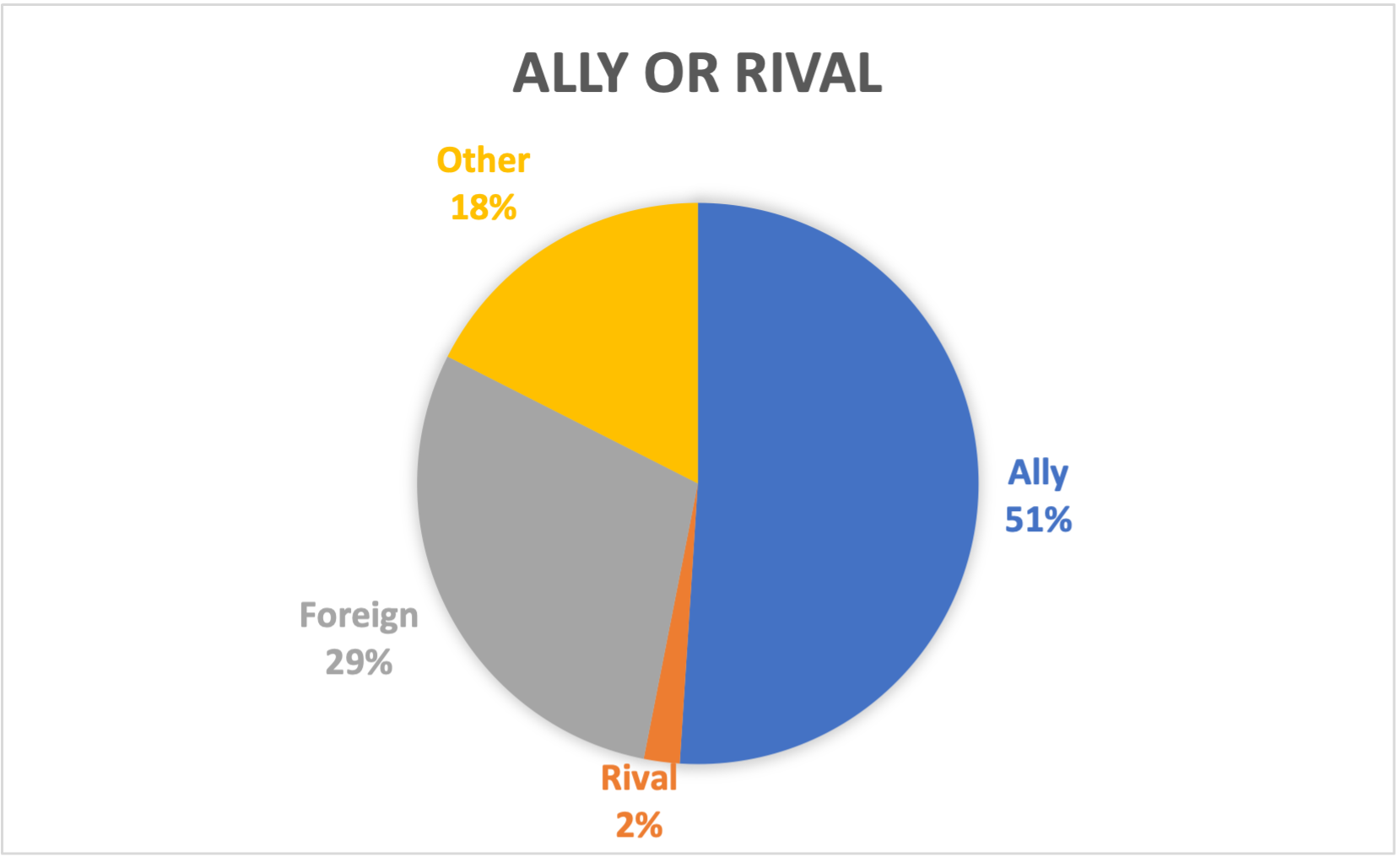

Analyzing the data, Talabani’s strategy appears to consist of meeting frequently with a narrow set of political allies from the Shi’a Coordination Framework (SCF) and associated groups and building relations with foreign diplomatic missions in Baghdad. Excluded from his public meeting list are political rivals like the Sadrists, Tishreen-affiliated groups, and, most importantly, the KDP.

The dataset does not express the fullness of the PUK’s strategy, but instead reflects the image that its leadership wants to communicate. There may be contacts with other groups, but they are not publicly acknowledged. In this sense, it is an incomplete picture, but one that is deliberately chosen by the PUK. I requested an interview with Talabani to hear directly about the party’s strategy, but this was declined by his office, citing his busy schedule.

Methodology and notes

This dataset was compiled in mid-February and updated thereafter, using Instagram as its primary source, cross-checked with Facebook. These are the most popular social media platforms in the Kurdistan Region. The posts are always written in Kurdish and often in Arabic; English is occasionally used when appropriate, for example, to describe a meeting with the U.S. ambassador. Talabani’s office also operates a Twitter account, which is the preferred social media platform for Western journalists and governments, but uses it far less frequently. Therefore, it is clear that the PUK leader is largely using these posts to communicate directly with a Kurdish and Iraqi audience.

Obviously, this data is limited to what Talabani’s office itself puts out on social media and focuses on set-piece diplomatic-style meetings. Contacts that occurred but were not posted online or did not take place in person do not show up. Also excluded from the dataset were internal PUK meetings3 or other political business primarily related to managing the internal affairs of Sulaymaniyah governorate4 that he had during the period. The data extracted included: date, location, and the names and affiliations of the principals involved in the meetings.5 These were each assigned codes to aid in analysis. Dates reflect when the posts were made on social media and are generally accurate to when the meeting took place.

Many meetings include multiple principals and some of them involve large groups. I have done my best to parse this, but the Kremlinology of Iraqi politics is complex. Any oversights or omissions are my own and I leave it to others to add nuance. Each contact with a principal has been counted separately and shows up in data and analysis related to contacts by affiliation. Sometimes principals with differing affiliations are involved in the same meeting. Other indicators, like date, location, or foreign country, are counted by meeting rather than contact to avoid double counting.

This dataset also does not account for the meetings held by other important PUK figures who also contribute to the party’s strategy of building relations with federal politicians, parties, and institutions. Meetings arranged by Talabani’s younger brother and KRG Deputy Prime Minister Qubad Talabani, PUK politburo members Shallaw and Darbaz Kosrat Rasul, current Iraqi Minister of Justice Khalid Shwani, former Iraqi President Barham Salih, current Iraqi President Abdul Latif Rashid, and various others are not covered here, although they may be involved in some meetings in various capacities.

Analysis

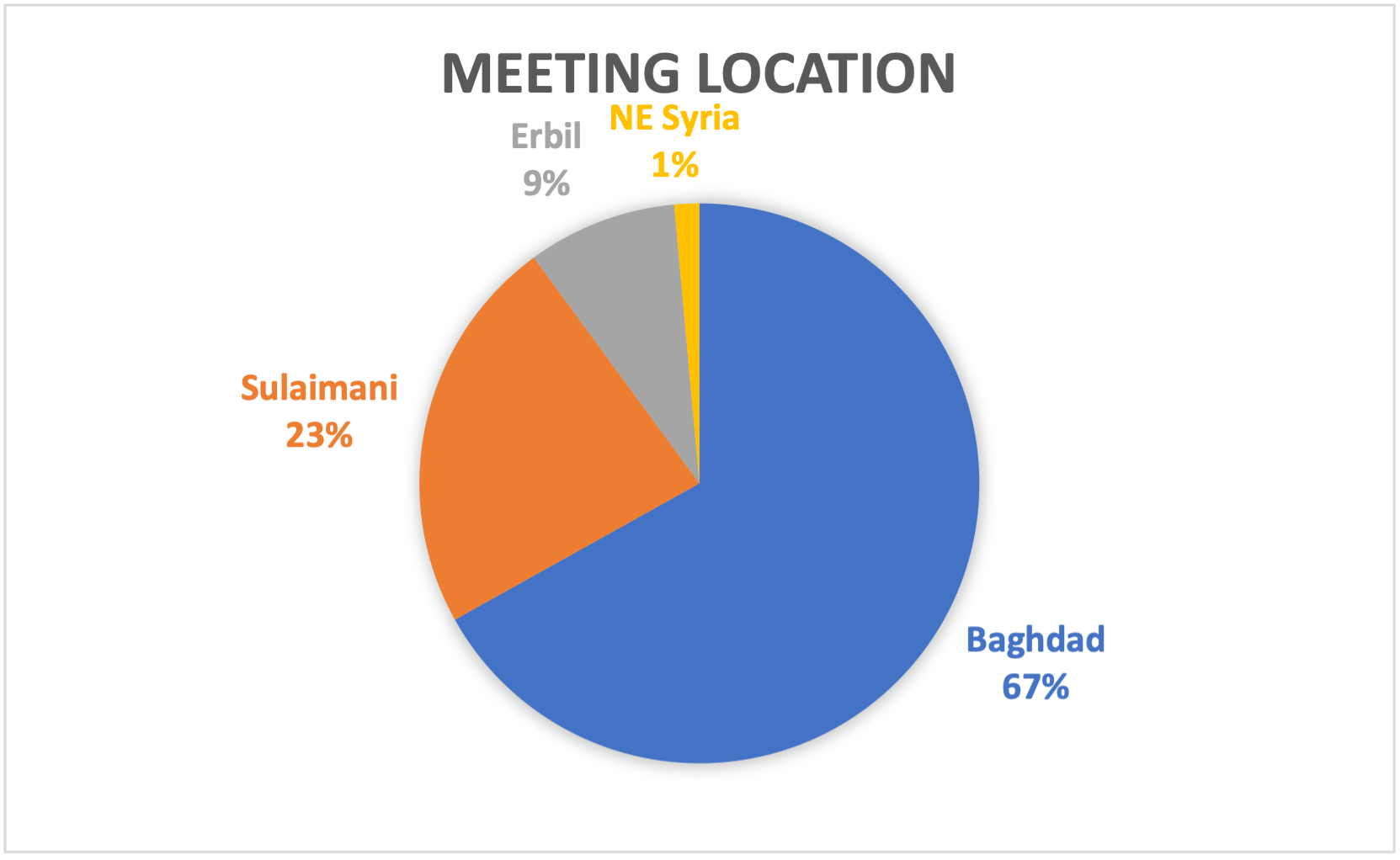

Over the past 15 months, Talabani has made an estimated 35 visits to Baghdad and is active while on the ground. Of the 139 meetings in the dataset, two-thirds took place in Baghdad (93 meetings).

The PUK’s home base of Sulaymaniyah was the second most frequent location for “external relations” meetings with about a quarter of the total (32). He had 12 meetings in Erbil, the Kurdistan Region’s political capital, and two meetings in northeastern Syria during a trip to Hasakah in December 2022.

Overall, Talabani met most frequently with members of the SCF, accounting for 33% of the total number of principal contacts. The person he met most often was Qais al-Khazali, leader of Asaib Ahl al-Haq (AAH), for a total of 16 times or an average of more than once a month. AAH is an Iran-backed militia that is part of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF). It was designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization by the U.S. State Department on Jan. 3, 2020, with Khazali and his brother Laith singled out as Specially Designated Global Terrorists under Executive Order 13224.

Talabani met with Rayan al-Kildani, leader of Christian party the Babylon Movement, 15 times and Muthanna al-Samarrai, a leader of Sunni faction Azm, on 13 occasions. Together with Khazali, they represent a distinct subgrouping in the dataset and were regularly present in the same meetings, if not always together.

An apparently warm relationship between Talabani and Kaldani was evident in the posts, showing the two laughing and embracing in big “bro” hugs. Some observers have speculated that Talabani plans to challenge the KDP’s dominance of seats in the Kurdistan Parliament reserved for Christians using Babylon-backed candidates.

Talabani also met regularly with other SCF leaders, including Nouri al-Maliki (13 contacts), Hadi al-Amri (9), Ammar al-Hakim (8), and Falih al-Fayyadh (5). Given the PUK’s positioning in recent years within the federal party bloc system, it is not unusual that he would frequently meet with his allies.

Talabani increased his visits to Baghdad during periods of crisis or parliamentary activity. For example, during Iraq’s tense political summer between June and August 2022, when Sadrist MPs resigned from the Council of Representatives and the SCF took over responsibility for forming the government, Talabani visited Baghdad nine times. Another spike in activity happened in October during negotiations over the Iraqi presidency, which the PUK retained after seeing off a challenge from the KDP.

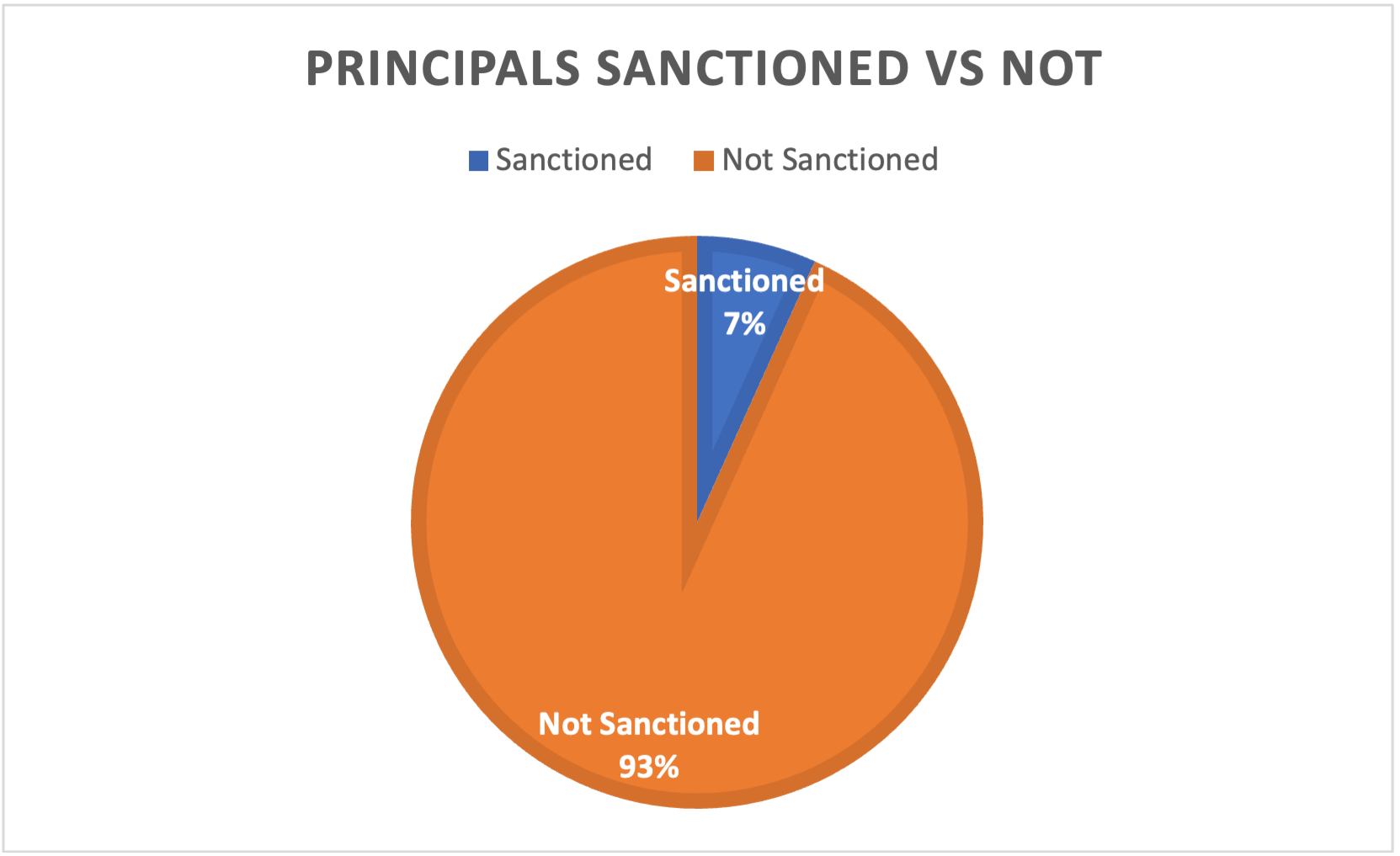

Controversially, Talabani frequently met with individuals sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department. In fact, the two principals he sees most often — Khazali and Kaldani — are both subject to Global Magnitsky Sanctions under Executive Order 13818. Three other sanctioned individuals appear in the dataset: Fayyadh, Abu Fadak al-Mohammedawi, and Ahmed al-Jubouri, who is known in Iraq as Abu Mazen. Like Khazali, Fayyadh and Mohammedawi are sanctioned under Executive Order 13224.

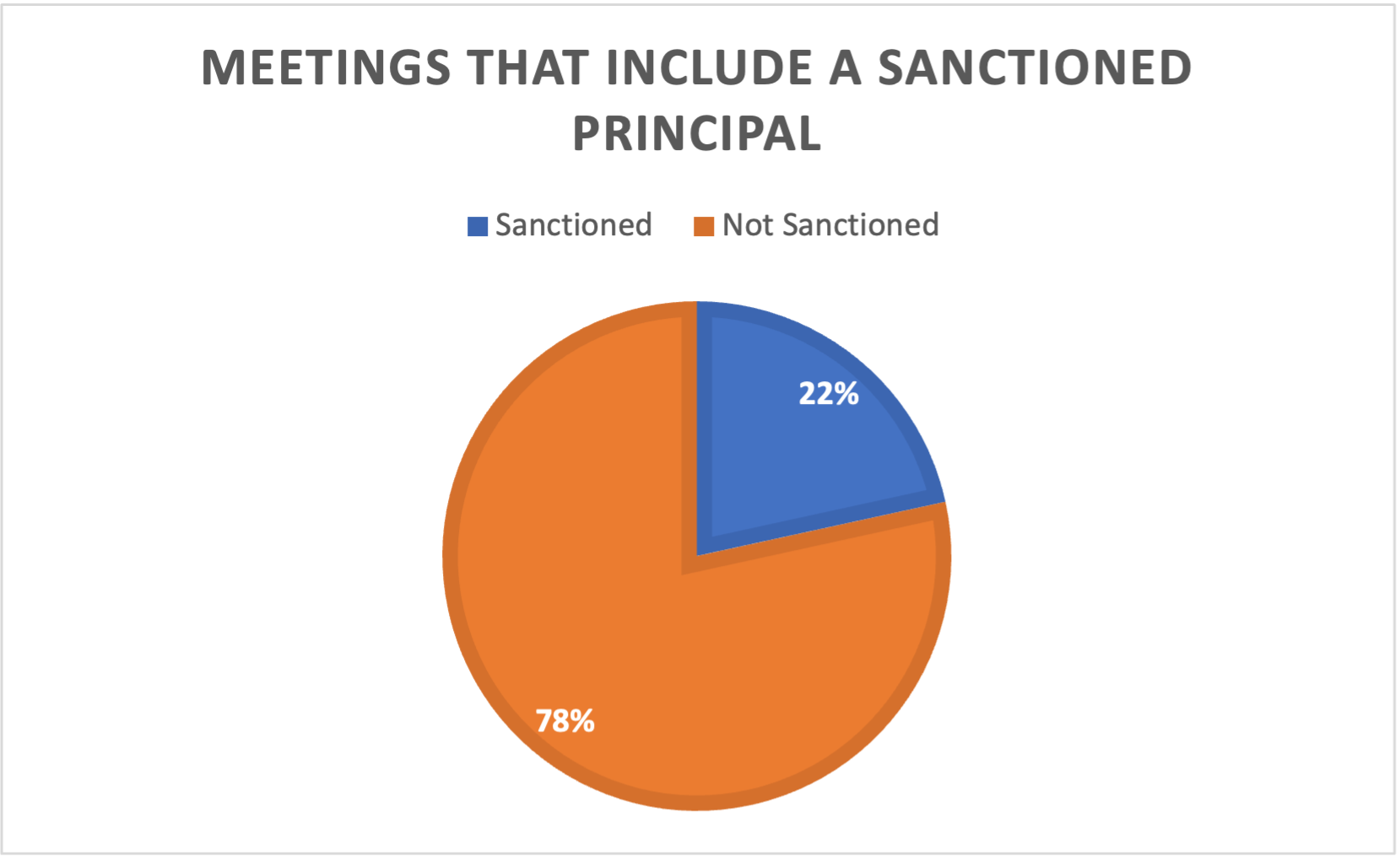

While these five men represent just 7% of the 75 individual principals with whom Talabani met, they were present in 22% of the meetings, indicating an outsized presence. These contacts are quite controversial, but Talabani has not publicly addressed criticisms of these meetings.

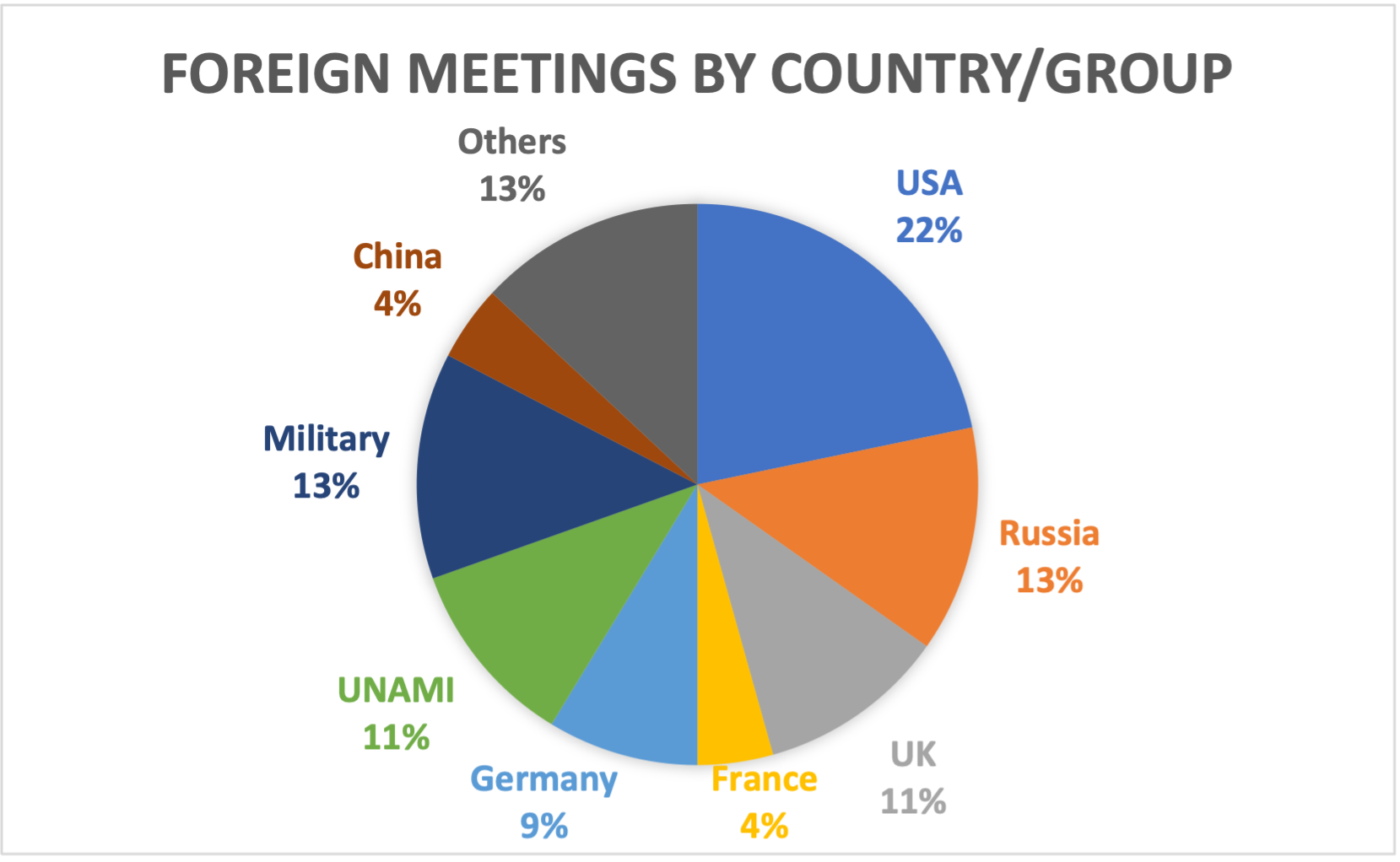

Talabani also held extensive meetings with representatives of foreign governments, militaries, and the United Nations. They accounted for 29% of principal contacts. U.S. diplomats were involved in the plurality (10) of such meetings, but Russian officials came in second (6). In fact, Russian Ambassador Elbrus Kutrashev was the foreign official Talabani met with the most times, if only because this period coincides with the replacement of Matthew Tueller with Alina Romanowski as U.S. ambassador.

There were five meetings each with British and U.N. officials, four with German diplomats, and two each with Chinese and French representatives. He also met with Italian, Finnish, European Union, Spanish, and Japanese officials. Reflecting his militaristic image, Talabani regularly met with foreign military delegations (6 times), particularly from the anti-ISIS Coalition.

While Talabani does meet occasionally with representatives from the consulates in Erbil, there is a distinct emphasis on the embassies in Baghdad in the dataset. This can be explained largely by his relative absence from the Kurdistan Region’s capital and Erbil-based diplomats’ infrequent visits to Sulaymaniyah. But where there is a will, there is a way and the numbers suggest an alternative strategy is possibly at play to establish direct links with missions in the capital, rather than going through those in KDP-dominated Erbil.

In the entire dataset, there was just one meeting with an Iranian official, Tehran’s Ambassador to Iraq Mohammed Kazem al-Sadiq. The PUK has close relations with Iran and Sulaymaniyah’s only international border is with Iran, making it a major trade partner. Iranian officials, including the late Qassem Soleimani, are regular visitors to Sulaymaniyah and Tehran maintains the city’s only consulate. Many of Talabani’s Arab allies in Baghdad also have close ties to Iran. Consequently, the dearth of contacts is puzzling, but can probably be explained by exclusion bias in the sample.

In addition to his political allies and foreign diplomats, the PUK leader is also working to build relationships with Iraqi government officials, with meetings including prime ministers, presidents, and cabinet officials. They account for 12% of the total contacts.

Notably, he also met with President of Iraq’s Supreme Judicial Council Faiaq Zidane four times, leading to accusations that Talabani was trying to influence the outcome of the lawsuits filed as a part of the PUK’s leadership struggle by ousted co-president Lahur Sheikh Jangi.

The remaining 9% of contacts involve Kurdish political parties other than the KDP (they will be discussed below) and other Iraqi and Kurdish political figures, like Ibrahim Bahr al-Uloom and Adham Barzani.

By omission, the data also shows with whom Talabani does not meet during his visits to Baghdad. There are no social media posts indicating that he has met with the Sadrists, Parliament Speaker Mohammed al-Halbusi, or Tishreen-affiliated opposition parties, all of whom are influential in different ways and represent major currents of Iraqi political life. It is, of course, possible that Talabani or other PUK officials have contact with these groups, but it is not part of the message that they want to communicate via the party leader’s social media.

What of Kurdistan?

It is notable also that Talabani almost never meets in person with the KDP’s senior leadership: The dataset suggests that he has met one of the big three Barzanis on just four occasions since the start of 2022. During that time, he met Kurdistan Region President Nechirvan Barzani twice (one of which was in the context of a meeting with a Coalition military official) and KDP President Masoud Barzani and KRG Prime Minister Masrour Barzani once each.

Talabani’s approach to Baghdad stands in stark contrast to that of the KDP, whose top brass rarely venture into federal Iraq. For example, since they began in their current positions in mid-2019, Nechirvan Barzani has visited the Iraqi capital six times and Masrour Barzani just three times.

It is well-known that the working relationship between the PUK and the KDP is extremely tense at the moment, but the lack of high-level meetings demonstrates the extent of that dysfunction, given the top-down decision-making systems in both parties. If the top leadership is not getting together, it is unlikely that progress is being made to resolve their issues.

Talabani has sent mixed messages to the KDP about their future together. At a commemoration of the 1991 Kurdish uprising, known as the Raparin, in Ranya on March 5, the PUK leader addressed the KDP, saying, “If you want this [peace and reconciliation], we will extend our hand for you. Let’s work for our people’s interest. Let’s struggle for this. We are ready if you want this.” Then he added in an angry and determined tone, “Otherwise, you would suffer losses.”

There has been some speculation among analysts about whether the PUK will split from the Kurdistan Region, make arrangements for a separate budget with Baghdad, or make some other dramatic break with the KDP; indeed, they might take this analysis as evidence of such a plan. Some also might see the PUK’s pursuit of good relations with Arab parties as a betrayal of Kurdish nationalism and reinforce the accusations of treason leveled at the party following the Iraqi Army's capture of Kirkuk in October 2017 after PUK-affiliated Peshmerga units left the city without putting up significant resistance. But both of these conclusions are overblown.

The PUK’s strategy of pursuing close ties with Baghdad should be viewed as a supplement to its traditional focus of working within the Kurdistan Region, rather than a substitute for that approach. The PUK is in a difficult spot: The finances of government institutions in its home base of Sulaymaniyah are in bad shape, it is still dealing with the effects of a prolonged leadership struggle, the KDP appears to be meddling in its internal affairs, and its traditional base of voters are disillusioned. It needs help and support and there is a logic in looking for it in Baghdad, but whether this strategy will pay off remains an open question.

Winthrop Rodgers is a journalist and researcher based in Sulaymaniyah in Iraq's Kurdistan Region. He focuses on politics, human rights, and political economy. He is an editor for The Nesar Record and past work has appeared in Rest of World, the Columbia Journalism Review, Al-Monitor, and the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Main photo: Bafel Talabani meeting with SCF leader Nouri al-Maliki. Photo from Talabani's official Facebook account.

Endnotes

- Historically, Kurdish parties do so in times of weakness, like Talabani cooperating with Iraqi forces against the Barzanis in 1968-69 and in 1996 when Masoud Barzani worked with Saddam Hussein to retake Erbil from the PUK during the Kurdish Civil War.

- This resulted in 193 “contacts.”

- For example, this visit to a PUK-affiliated security forces unit on Feb. 19, 2023.

- For example, this meeting on March 6, 2022 with students who had staged major protests the previous year.

- In one case a principal’s affiliation changed midstream: Mohammed Shia al-Sudani was coded as SCF until he became prime minister on Oct. 27, after which he was coded as Iraqi government.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.