Summary

Kuwait plays a larger role than is often assumed in America’s present and future military plans in the Middle East. Though small in size, the country is strategically significant because of its key geographical location in the northeast corner of the Arabian Peninsula and astride the Europe-Asia air corridor, its great seaports, rich petroleum holdings, regionally unique system of constitutional monarchy, and propensity toward taking on a helpful diplomatic mediator role in regional conflicts. Moreover, Kuwait has long been an indispensable security partner of the United States in the broader Middle East mainly due to its access, military basing, permissions, training, logistics, financial cost, and safety. But as Washington prioritizes the Indo-Pacific, with the attendant military drawdown this causes in the Middle East, it is critical that the security arrangement between the United States and Kuwait is reconfigured, with an eye toward developing the Kuwaiti defense system’s Phase Zero preparations as well as its military’s ability to fight alongside U.S. forces.

Executive Summary

Kuwait plays a larger role than is often assumed in America’s present and future military plans in the Middle East. Though small in size, the country is strategically significant in part because of its geographical location. It sits in the northeast corner of the Arabian Peninsula, sharing land borders with Iraq to the north and Saudi Arabia to the south and west, as well as maritime borders with Iran. It also lies astride the Europe-Asia air corridor and has great ports — assets that are particularly useful for the U.S. Navy and U.S. defense planners with responsibilities for the Middle East.

Kuwait additionally plays an outsize role on the international stage because it is rich in oil, holding approximately 7% of global reserves, with a current production capacity of about 3.15 million barrels per day, making it the 10th-largest producer of petroleum and other liquids in the world. On top of that, Kuwait has the world’s oldest, and since last year, third-largest sovereign wealth fund by assets, reaching a record $700 billion, much of which, importantly, is invested in the United States.

Politically, Kuwait matters because it is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system of government that is rather unique in the Arab world. Although the Al Sabah ruling family dominates, a credible participatory politics does exist in Kuwait, which is not the case in most of the rest of the region.

In regional affairs, Kuwait has historically espoused neutrality and played a useful role as an independent mediator, though perhaps at the expense of a more proactive foreign policy. Washington, and U.S. Central Command’s (CENTCOM) leadership in particular, has always appreciated Kuwait’s diplomacy, which has helped calm tempers in the region, be it in Yemen over the past few years or during Qatar’s 2017-21 diplomatic crisis with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, and Egypt.

Designated as a Major Non-NATO Ally since 2004, Kuwait is an indispensable partner to the United States in the broader Middle East mainly due to its access, basing, permissions, training, logistics, financial cost, and safety. Unlike any other partner around the world — with the exception of Bahrain — Kuwait allows relatively unhindered movement of U.S. military personnel and equipment. It hosts the fourth-largest foreign U.S. military presence, behind only Germany, South Korea, and Japan, and it is the forward headquarters of U.S. Army Central, the Army component of CENTCOM. Kuwait is the best training area for the U.S. military outside of the United States, Germany, or South Korea. The largest U.S. air logistics facility in the region is in Kuwait, at the country’s international airport. Most of the time, the United States can use Kuwait to freely transit personnel and equipment into other countries for various operational contingencies across the region, which includes the recently concluded fight against the Islamic State and the August 2021 exit from Afghanistan.

Since Operation Desert Storm in 1991, Kuwait has financially compensated the United States for maintaining forces on its soil. The Kuwaiti government, unlike most others in the region and around the world that are partnered with Washington, does not charge for the use of Kuwaiti land, and it offers the United States a very cheap rate for electricity and other utilities. Among other financial contributions to various U.S. military operations in the region, Kuwait has supplied the United States with approximately $200 million per year to help it contain and stabilize Iraq. And during and after Desert Storm, Kuwait paid the United States roughly $16 billion to offset U.S. war costs. Last but not least, Kuwait gave free plane rides to dozens of American evacuees from Afghanistan, sending them back home on Kuwaiti Boeing 777s.

U.S. force protection in Kuwait is not a concern, unlike several other places including Iraq, with superior support provided by the host nation, according to CENTCOM. That the Kuwaiti government permits U.S. troops to freely provide for their own security also is key.

The United States pursues the following military activities in Kuwait in support of U.S. strategic objectives across the broader Middle East:

- Multi-domain U.S. military training for various regional contingencies.

- Training with Kuwaiti forces through bilateral and multilateral military exercises and seminars.

- Support for ongoing operations in theater, such as Operation Inherent Resolve and Operation Spartan Shield, with the help of stationed (or visiting) U.S. troops and prepositioned equipment in Kuwait.

Despite robust security cooperation between the United States and Kuwait, the latter’s military preparedness, readiness, and organizational approach to a potential war in the region (most likely with Iran) considerably lags behind most of its Gulf Arab partners as well as its main regional adversary, Iran, and the latter’s Shi’ite agents in Kuwait and militant allies in Iraq.

While a couple of other Gulf Arab militaries have gradually moved to the Force Provider/Joint Warfighter model, Kuwait prepares for and organizes its defense largely like it did in 1990, before Saddam Hussein’s forces invaded. Kuwait’s current approach to steady-state operations leans almost exclusively on U.S. protection and involvement. In Phase Zero, this is not a sustainable approach for effectively and efficiently countering the increasingly complex security challenges and threats in the region.

As Washington prioritizes the Indo-Pacific, with the attendant military drawdown this causes in the Middle East, it is critical that the security arrangement between the United States and Kuwait is reconfigured. Moreover, the latter’s approach to Phase Zero must rise to meet the threats posed by Iran, regional militias loyal to Tehran, and Sunni terrorist groups. For both its own defense and the general security of the region, Kuwait must improve its ability to generate credible combat power and defend itself on its own or in a combined effort with the United States, should a mutual threat materialize.

While Kuwait has continued to equip itself in the last two decades with modern U.S. weapons systems, its ability to employ and sustain these weapons to actively defend Kuwait has not kept pace with its acquisitions. The defense of Kuwait now and into the future will benefit not from more weapons but from improving how the country organizes its command structures into a modern system supporting enhanced joint force employment of its military capabilities.

Among the structural defense reforms Kuwait should pursue is the formulation and operationalization of a capstone document that defines the missions of the military, specifies the nation’s joint warfighting concept, and plans and allocates forces for steady-state operations. This document would create a “north star” for Kuwait’s daily operational planning with CENTCOM and future capability-based resource planning with the Pentagon’s Defense Security Cooperation Agency, much like the Unified Command Plan, Contingency Planning Guidance, and Global Force Management Process do for the United States.

Kuwait’s ability to fight — and fight jointly — is vital not only for the country’s defense but also for CENTCOM’s theater plans. While CENTCOM does have a contingency plan for each of its partners in the region — in other words, a plan to repel or defend against a major Iranian threat — this plan would benefit tremendously from direct and tangible contributions from the regional partners, including Kuwait. If Kuwait is not doing much in steady-state operations — and it appears it is not, with the exception of buying equipment — then its contributions during wartime to a coalition fight will likely be negligible, at best.

To remedy this status quo, the Kuwaiti military must establish two standing joint force commands with two joint force commanders, each responsible directly to the Kuwaiti National Command Authority for executing critical defense missions: one in the eastern part of the Gulf, in the littoral areas and territorial waters of the country, and the other across Kuwait’s northwestern land borders with Iraq.

Kuwaiti service commanders, along with members of the Kuwaiti National Guard, would provide their best officers for assignment to these standing joint force commands. Joint force commanders and staffs, reporting to and working under the close supervision of Kuwaiti Armed Forces Commander Lt. Gen. Khaled Saleh Al Sabah, would be tasked with conducting joint operational planning for steady-state operations and exercises to ensure higher levels of joint operational readiness. These joint operational plans would, among other things, describe the threat and operational environments and how (i.e., the ways) military capabilities/the joint force (the means) are used in time and space to achieve operational objectives (the ends). Efforts to pursue other structural defense reforms — including human resource management, defense resource management, logistics, and the rule of law — should follow once the operational shortfalls have been addressed.

However, the Kuwaitis are unable on their own to engage in effective defense institution building. The United States, and especially CENTCOM, must play a major role in this process, as they have a moral and strategic responsibility to leverage the more than three decades of cooperation since the First Gulf War.

We must recognize that this is a sensitive moment and perhaps even an inflection point in U.S.-Arab security relations. While other Gulf Arab partners are vastly unsure about America’s security commitment and are in the midst of figuring out how they are going to defend themselves against Iranian aggression — on their own or with the help of others, possibly including the Chinese and the Russians — Kuwait still has faith in U.S. protectorship. But we shouldn’t take this continued support for granted. We must reward and nurture this faith by making things right for both sides. We have a unique opportunity in Kuwait to show the Kuwaitis and all other Arab partners that it is, indeed, possible to build a new and more effective model for security cooperation that serves mutual interests.

We don’t need two divisions of tanks stationed in Kuwait, just like we don’t need a brigade combat team and two fighter squadrons in the country. The Kuwaitis have enough firepower of their own. What we need is tailored and more consistent U.S. advice on defense governance and, specifically, on how to create a Kuwaiti joint force.

Apr. 12, 2019. Photo by Marine Corps Sgt. Aaron Henson via DoD.

Introduction

Its leadership has not said it explicitly, but U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) — the U.S. Geographic Combatant Command in charge of all U.S. military operations and security cooperation activities in the broader Middle East — is quietly undergoing a historic transition. This process has been unfolding for years, though the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021 and Operation Inherent Resolve’s (OIR) switch five months later from a combat mission to one focused on advising, assisting, and enabling Iraqi partner forces, have merely accelerated it.

The political-strategic driver of change in CENTCOM is a bipartisan consensus in Washington on the increasing importance of other priority regions, such as the Indo-Pacific and Europe. Codified by two consecutive national defense strategies, this consensus suggests a diversion of resources away from the Middle East (though in reality, a major transfer of such resources or reduction of CENTCOM’s forces has yet to take place). The guiding principle of CENTCOM’s makeover is enhanced security cooperation with regional partners and, ultimately, military integration with and among (at least some of) them to safeguard collective security interests. The less fighting the U.S. military does in the region, U.S. officials believe, the more it can think about and prepare for the pacing challenge of Beijing’s People’s Liberation Army.

It is an incredibly tough assignment for new CENTCOM Commander U.S. Army Gen. Michael “Erik” Kurilla — arguably tougher than the one handed to his late predecessor U.S. Army Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf, who, 32 years ago, was asked to expel Saddam Hussein’s formidable army from Kuwait while leading one of the largest international military coalitions in the world (which was no easy feat).

It’s also a unique mission since CENTCOM was born on January 1, 1983. Though the official launch of the Command happened during the Reagan administration, it was President Jimmy Carter who created CENTCOM’s predecessor three years earlier. The Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force, as it was called, supported the Carter Doctrine, which suggested that any outside (read Soviet) attempt to gain control over the Persian Gulf would be perceived as an assault on U.S. national interests and met with military force. CENTCOM’s new mandate represents a clear break from this doctrine, or its successor, the Reagan Corollary, which focused more on the threat posed by the Islamic Republic of Iran. Now, CENTCOM is preoccupied with gradually building what it calls a Regional Security Construct, whose pillars are integrated air and missile defense, maritime security, crisis response, special operations forces, and theater sustainment and fires.

Successive American administrations in the post-9/11 era talked a good game when it came to strengthening regional partnerships, but they never bothered to truly conceptualize and practically enable a more integrated security framework in the region, with the United States serving as a hub. Now, Gen. Kurilla is in roughly uncharted territory, where he faces the additional challenges of fewer resources at his disposal as well as anxious Arab partners who seem less eager to fully cooperate with Washington due to perceived concerns about U.S. inconsistency and unreliability in recent years.

Luckily for Washington, Kuwait is not one of those apprehensive or hesitant partners. Of course, this does not mean that the Kuwaitis have no issues at all with Washington or don’t ever question U.S. policy; but the trust they have in the United States is unmatched among Arab partners. Maybe it’s because the Kuwaitis recognize they don’t have better security options. Or maybe they’re eternally grateful to the Americans for liberating their country from Iraqi occupation. The reasons for this mutual, deep trust are less important. What matters most is that Kuwait is all in when it comes to the security partnership with the United States. This is quite important for Washington, and CENTCOM in particular, because contrary to conventional wisdom, Kuwait has a lot to offer, some of which is unique in the region.

Kuwait hardly ever comes up in discussions about America’s Arab partners in the region. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Qatar, and to some extent Jordan dominate the headlines. Even when Kuwait is talked about, it’s not exactly in glowing terms. Middle East and military analysts often ask why, decades after Operation Desert Storm, do we still have such a large footprint in peacetime Kuwait? Wouldn’t U.S. strategic interests be better served by placing a percentage of these 13,500 troops in another priority region or by bringing them back home?

These are fair and policy-relevant questions, but my goal in this paper is not to opine on the size of our military presence in Kuwait and whether it should be reduced or maintained (although, candidly, it would not be outlandish to argue that there is sufficient room for a responsible diminution of the force). Rather, it is to shed light on the military significance of Kuwait to the United States and on the role the country plays in present and future U.S. military plans in CENTCOM’s Area of Responsibility. Kuwait is likely an undervalued partner by many — though certainly not by U.S. military leadership — partly because it is vastly understudied and thus widely unknown.

In my recently released book Rebuilding Arab Defense, I analyzed in depth what it would take for both the United States and its Arab partners to meaningfully upgrade their security cooperation. I looked at Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Lebanon, and the UAE. Here, I will examine Kuwait, and like I did with those previous case studies, I will pay close attention to the main defense reforms the country has to make to be able to better defend itself against external aggression and reduce its security dependence on a U.S. military that, in accordance with civilian policy directive, will further draw down in the region as it shifts its attention to the Indo-Pacific.

Kuwait’s Strategic Relevance

Despite being a little smaller than New Jersey, with 4.4 million people, two-thirds of whom are expatriates, Kuwait is strategically significant to the United States on several levels. For one, its geographical location makes it a prime spot for regional connectivity. It sits in the northeastern corner of the Arabian Peninsula, sharing land borders with Iraq to the north and Saudi Arabia to the south and west, as well as maritime borders with Iran. It also lies astride the Europe-Asia air corridor and has great ports — assets that are particularly useful for the U.S. Navy and U.S. defense planners with responsibilities for the Middle East.

Kuwait also plays an outsize role on the international stage because it is rich in oil, holding approximately 7% of global reserves with a current production capacity of about 3.15 million barrels per day, making it the 10th-largest producer of petroleum and other liquids in the world. On top of that, Kuwait has the world’s oldest and, since last year, third-largest sovereign wealth fund by assets, reaching a record $700 billion, much of which, importantly, is invested in the United States.

Politically, Kuwait matters because it is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system of government that is rather unique in the Arab world (though official political parties are banned). The head of the state, also called the emir, is the commander-in-chief, per article 67 of the Constitution (the crown prince is the deputy commander-in-chief). He commissions and discharges officers in accordance with the laws and directs the employment of military forces.

Chaired by the crown prince and the prime minister, the Higher Defense Council is nominally responsible for defending the country. It addresses major matters of defense policy. Technically, the minister of defense, currently Sheikh Talal Khaled Al Ahmad Al Sabah, has a higher rank than all other civilian and military leaders of the Kuwaiti Armed Forces (KAF); but the KAF commander, Lt. Gen. Khaled Saleh Al Sabah, is the source of expertise on all things defense. Since his promotion in October 2020, he has almost always represented Kuwait in meetings with senior U.S. officials to discuss the bilateral security relationship.

The emir is always from the ruling Al Sabah family. Although the family dominates, there is credible participatory politics in Kuwait, which is not the case in most of the region. The National Assembly, or Majlis al-Umma, has the power to question and dismiss ministers, including the prime minister, and to both propose and block legislation. With regard to national security issues, there’s a higher level of parliamentary oversight, especially on defense spending, than anywhere else in the Arab world (the Majlis issues the Defense Support Budget by law). Some from the region and elsewhere view Kuwait as a model for the rest of the Gulf Arab monarchies, but others, especially in Manama and Abu Dhabi, worry that its pluralistic system, which creates space for and gives a voice to the Muslim Brotherhood, invites political instability (a number of Kuwaitis happen to agree with this assessment, and at present there’s a national debate regarding the merits of instituting systemic changes).

In regional affairs, Kuwait has historically espoused neutrality and played a useful role as an independent mediator, though perhaps at the expense of a more proactive foreign policy. In recent years, the Kuwaiti leadership did everything it could to end the Qatar diplomatic crisis that began in 2017, ultimately succeeding in helping broker the January 2021 al-Ula Declaration, which restored ties between Doha and the Riyadh-Abu Dhabi-Manama axis. In Yemen, before his passing in September 2020, Kuwaiti Emir Sabah al-Ahmad Al Sabah kept emphasizing mediation in an effort to reach a political solution to the conflict between the Saudi-led coalition and the Yemeni Houthis. Washington, and CENTCOM’s leadership in particular, has always appreciated Kuwait’s diplomacy, which has helped calm tempers in the region. A former CENTCOM commander recalls how Kuwaiti military leaders played an instrumental role in moving past the loss of momentum and friction associated with the 2017 Gulf rift and in building consensus among Gulf Arab chiefs of defense on regional security matters.

The United States first established official relations with Kuwait in 1961, after the country gained its independence from the United Kingdom (a U.S. consulate was established in the country exactly a decade before). But contact goes all the way back to the late 1800s, when American missionaries traveled to the Gulf region to spread the Christian faith (which did not work out very well), foster cultural dialogue, and engage in humanitarian activities. Most Americans, of course, remember Kuwait from the First Gulf War in 1990-91 when the United States stopped Saddam Hussein from gobbling up his small, energy-rich neighbor. But three years before that transformative event in the Middle East, during the Iran-Iraq War, the United States launched a complex maritime security operation to ensure that 11 Kuwaiti tankers could freely navigate through the Persian Gulf by reflagging them (Iranian air attacks on ships focused on Kuwaiti vessels and those bound for Kuwaiti ports because Kuwait had sided with Iraq against Iran in their eight-year war).

Designated as a Major Non-NATO Ally since 2004, Kuwait is an indispensable partner to the United States in the broader Middle East mainly due to its access, basing, permissions, training, logistics, financial cost, and safety. Yet Kuwait does a poor job at explaining its strategic importance to American audiences largely because it is uncomfortable doing so. Kuwaiti culture plays a role. Kuwaitis much prefer not to be perceived as a needy partner. Asking Washington for even the smallest thing, in their view, is frowned upon (in contrast with other Gulf Arabs), so they often feel reluctant to make a case for their country to U.S. officials and members of Congress.

- Access: Unlike any other partner around the world with the exception of Bahrain, Kuwait allows relatively unhindered movement of U.S. military personnel and equipment. In other words, U.S. access is impeccable, with the Kuwaiti government imposing no bureaucratic hurdles and no taxes.

- Basing: Thanks to a 1991 formal Defense Cooperation Agreement (which remains in effect and includes a Status of Forces Agreement) and a 2013 Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement, Kuwait hosts the fourth-largest foreign U.S. military presence behind only Germany, South Korea, and Japan. In addition, Kuwait is the forward headquarters of U.S. Army Central (ARCENT), the Army component of CENTCOM, which commands multiple units on nine-month tours. In 2020, ARCENT deployed, employed, and redeployed 12 brigade headquarters and 20 battalion-level units mostly organized in “Task Force Spartan.”

- Permissions: Most of the time, the United States can use Kuwait to freely transit personnel and equipment into other countries for various operational contingencies across the region, which includes the recently concluded fight against the Islamic State. This is fairly exceptional, as throughout history even many treaty allies of the United States have prevented U.S. forces from flying over or transiting their territory during military operations (two such examples are European prohibitions on U.S. overflights to bomb Libya in 1986 and a Turkish veto to the transit of U.S. forces to Iraq to launch military operations in 2003).

- Training: Kuwait is the best training area for the U.S. military outside of the United States, Germany, or South Korea. Located in the northwestern Kuwaiti desert, the 500-square-kilometer Udairi Range Complex allows U.S. forces to fire almost every weapon in the U.S. inventory and to train with Kuwaiti forces. Annually, ARCENT conducts approximately 20 medium and large-scale military exercises with regional partners.

- Logistics: The largest U.S. air logistics facility in the region is in Kuwait, at the country’s international airport. Kuwait is one of five U.S. Army Prepositioned Stocks (APS) sites worldwide. The APS program is a cornerstone of the Department of Defense’s ability to rapidly project power, and it sends a clear signal of U.S. commitment. Sets of equipment, such as all the tanks and trucks of an armored brigade, are prepositioned in climate-controlled facilities. During Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003, Kuwait provided up to 60% of its territory for coalition use.

- Financial cost: Since Desert Storm, Kuwait has financially compensated the United States for maintaining forces on its soil. The Kuwaiti government, unlike most other U.S. partners in the region and around the world, does not charge for the use of Kuwaiti land, and it offers the United States a very cheap rate for electricity and other utilities. Among other financial contributions to various U.S. military operations in the region, Kuwait has supplied the United States with approximately $200 million per year to help it contain and stabilize Iraq. And during and after Desert Storm, Kuwait paid Washington roughly $16 billion to offset U.S. war costs. Last but not least, Kuwait gave free plane rides to dozens of American evacuees from Afghanistan, sending them back home on Kuwaiti Boeing 777s.

- Safety: U.S. force protection in Kuwait is not a concern, unlike several other places including Iraq, with superior support provided by the host nation, according to CENTCOM. “You’re a lot safer in Kuwait than you are in Chicago, New York City, or Los Angeles. It’s a good place to be for an American soldier,” said a senior U.S. military serviceman in Kuwait. That the Kuwaiti government permits U.S. troops to freely provide for their own security also is key. In February 2022, force protection in Kuwait got a new facility at Ali al-Salem Air Base.

US Military Activities in Kuwait

In an October 2016 interview, former ARCENT Commander Gen. Michael Garrett transparently stated that “a lot of people don’t realize what we do [in Kuwait] on a daily basis.” He was right. To this day, it’s unclear to many American Middle East scholars and practitioners, even the more seasoned ones, what the U.S. military does in peacetime Kuwait. The following identifies the sets of military activities the United States pursues in the country in support of U.S. strategic objectives across the broader Middle East:

1. Multi-domain U.S. military training for various regional contingencies. It all starts with ARCENT and Operation Spartan Shield, which is focused on maintaining a presence in theater. Spartan Shield primarily allows ARCENT to execute its contingency plans and respond to immediate crisis situations.

Lately, given the rise of the unmanned aerial threat in the region and elsewhere, the U.S. Army and U.S. Air Force have emphasized developing and training with a suite of counter-drone weapons, including Mobile Low, Vehicle Integrated Defense Systems. This Mine-Resistant Ambush-Protected vehicle system uses a combination of sensors to detect aerial threats before disabling them, either through electronic jamming or destroying them with a 30-millimeter cannon or the Coyote small drone. At Ali al-Salem Air Base in Kuwait and elsewhere, the U.S. Air Force’s 386th Expeditionary Security Forces Squadron has created counter-drone seminars to better detect, track, identify, and defeat the threat (a process called the “kill chain”).

In aviation and on land, members of the U.S. Air Force and U.S. National Guard have trained in Kuwait on various missions. In January 2022, 40th Combat Aviation Brigade Task Force Phoenix’s nine-month mission came to an end, leading to its transfer to Task Force Eagle, 11th Expeditionary Combat Aviation Brigade. The former executed air-ground operations in Kuwait, Iraq, eastern Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia in support of OIR and Operation Spartan Shield. It consisted of more than 1,700 soldiers equipped with UH-60 Black Hawk, CH-47 Chinook, AH-64 Apache, AS-532 Cougar, and NH-90 Puma helicopters, as well as MQ-1C Gray Eagle unmanned aerial systems.

U.S. soldiers also attend courses in Kuwait on air assault. At Camp Buehring, U.S. Army personnel attend a 12-day class that trains them on how to become air assault qualified. Task Force Spartan is in charge of the course, which was launched for the first time in 2017, graduating that year 269 U.S. service members. Nearby, at Camp Arifjan, U.S. soldiers from the 434th Chemical Company, 1st Battalion, 194 Armor Regiment, and Task Force Bastard conducted in August 2021 joint chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear decontamination training with U.S. Navy Explosive Ordnance Disposal technicians.

2. Training with Kuwaiti forces through bilateral and multilateral military exercises and seminars (the Kuwaitis also train with the British military in various domains including urban warfare and reconnaissance). One important point of clarification about these exercises is in order, though: the United States does not necessarily emphasize training with Kuwaiti or other partner forces in the region on offensive kinetic operations. Many of the exercises, such as visit, board, and search and seizure in the maritime domain, are defensive in nature but certainly could be used offensively. Another example is how U.S. and partner forces from the special operations community train to seize a facility and liberate an area from terrorist control, which could be either offensive or defensive (though the Pentagon’s 127 Echo authority and program is purely for offensive counterterrorism operations conducted by U.S. special operations forces, sometimes in partnership with local forces). For aviation, the U.S. Air Force teaches and trains regional partners in aerial combat, which, again, could be employed for defensive or offensive purposes. In OIR, CENTCOM regularly taught regional partner forces how to conduct kinetic operations against the Islamic State.

The latest U.S.-Kuwaiti military exercise, in which Bahrain and Saudi Arabia participated, took place in March 2022 in Fort Carson, Colorado, and it lasted two weeks. Eagle Resolve 2022 was a computer-based, scenario-driven command post exercise meant to enhance integration between the United States and its regional partners in the area of air and missile defense. The Kuwaitis also learned how their military and civilian institutions could better cooperate and coordinate on crisis management, said Kuwaiti Brig. Gen. Mubarak al-Zoubi.

In January of this year, Kuwaiti Air Force students trained with their American counterparts on technical readiness and maintenance of their newly purchased but yet-to-be-delivered F/A-18E/F Super Hornets in the Center for Naval Aviation Technical Training Unit Oceana in Virginia Beach. This new training site was added to San Antonio, Texas, and Lemoore, California — where the Kuwaitis have attended courses since 1993 — since the Kuwaiti Air Force upgraded their fleet from the legacy F/A-18 Hornets to the Super Hornets. The Kuwaitis also have trained over the years with U.S. Airmen at Joint Base Charleston, South Carolina on how to operate and maintain their C-17 Globemaster III aircraft, which provides the Kuwaiti Air Force with a regional as well as long-range strategic airlift capability.

2021 exercise at the Udaira military range. Photo by YASSER

AL-ZAYYAT/AFP via Getty Images.

In November 2021, Kuwait concluded with the United States and Saudi Arabia a two-week gunnery ground and air exercise called Gulf Gunnery 2021, at the Udairi Range in Kuwait. Rather shockingly, it was the first time in 30 years that all three countries came together to train militarily. Brig. Gen. Mohammad al-Dhafiri, the commander of the Kuwaiti Land Forces, said that the exercise included seminars as well as practical and field exercises designed to execute joint ground operations. It began with crew-level training on individual vehicles, then it progressed to platoon-level training, culminating with combined company-level gunnery. M1 Abrams tanks, Bradley fighting vehicles, helicopters, rocket launchers, and paratroopers were all used in Gulf Gunnery 2021.

In June 2021, the Kuwaiti Navy and Coast Guard, which comprise very modest patrol boats, and U.S. Naval Forces Central Command (NAVCENT) conducted bilateral exercise Eager Defender 21 in Kuwait and the northern waters of the Gulf, marking the capstone in a series of bilateral exercises between Kuwaiti and American naval forces. The exercise, which employed a guided-missile cruiser, a patrol coast ship, a patrol boat, a coast guard maritime engagement team, and an expeditionary mine countermeasures company on the part of the Americans, focused on visit, board, search and seizure, high-value unit defense, search and rescue, explosive ordnance disposal, and shipboard gunnery operations.

A year before that, also in the summer, the Kuwaiti Coast Guard and the U.S. Navy conducted joint patrols in northern Gulf waters as part of the U.S.-led Combined Task Force (CTF) 152, of which Kuwait and several other Arab countries are part. Kuwait currently leads CTF 152, which conducts maritime security operations in the Persian Gulf. In September 2018, the Kuwaiti Coast Guard became the first in the region to command CTF 152. The Kuwaitis practiced communication and joint maneuvering drills, interacted with local commercial shipping in the international waters of the Gulf, and searched for potential smugglers.

In August 2018, the Kuwaiti Navy joined the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard as well as the Iraqi Navy in a trilateral exercise in the northern part of the Gulf to learn more efficient and effective maritime security tactics. The exercise included drills on live-fire gunnery, visit, board, search and seizure, maritime infrastructure protection, search and rescue, and high-value unit protection operations. Later that year, U.S. Marines and a Kuwaiti Marine Battalion trained on urban warfare operations at Kuwait Naval Base to strengthen both forces’ warfighting abilities in a close, urban environment. The Kuwaitis also have an annual exercise with the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marines called Eager Mace. The Americans train the Kuwaitis on basic marksmanship skills near Camp Buehring.

In February-March 2016, Kuwaiti forces trained with NAVCENT in an amphibious and ground exercise called PHILBLEX-16. The exercise partly sought to improve the tactical proficiency of the Kuwaitis and broaden bilateral cooperation, but its chief purpose was to provide joint training to U.S. Navy and Marine units on complex and large-scale amphibious assault operations. “The point is to do an amphibious operation that brings everyone together on one coalition force,” said Vice Adm. Kevin M. Donegan, then the commander of NAVCENT, U.S. Fifth Fleet, and Combined Maritime Forces.

On land, in January-February 2020, the Kuwaiti Land Forces and the U.S. Army held Dasman-1 joint exercises in the Udairi Range, which were attended by high-level Kuwaiti and American military officers and involved live ammunition and artillery training. A few weeks later, the Kuwait Land Forces Field Artillery Regiment provided support during a live-fire exercise called Dasman Shield, also on the Udairi Range, to U.S. joint terminal attack controllers part of the 82nd Expeditionary Air Support Operations Squadron.

Simulating an attack across Kuwait’s border (and ultimately drawing lessons from that scenario), Desert Observer involved the U.S. Army and Kuwaiti forces in September 2017, near the Udairi Range. The multi-day, combined exercise “showcased [the U.S.] ability to rapidly deploy in conjunction with […] partners in the Kuwaiti Land Forces and Ministry of Interior to decisively encounter a threat to Kuwait or any […] other regional partners,” said Capt. John Pelham, the commander of Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry Regiment. The main weapons systems used in Desert Observer were U.S. M1A2 Abrams tanks and armored fighting vehicles equipped with long-range advanced scout surveillance systems.

In addition to these bilateral and multilateral exercises, Kuwait has taken part in much larger annual and biennial exercises. One of these is Eager Lion. Involving the U.S. and Jordanian militaries as well as several thousand military personnel from land, naval, and air forces across a few dozen countries from around the world, Eager Lion is the most significant in the region. The King Abdullah II Special Operations Training Center in Amman hosts some of the Eager Lion drills. Using both light and heavy weapons, the exercise trains on multiple terrains over a period of roughly two weeks for realistic contingencies. The program conducts various live-fire exercises, including air assaults, long-range bomber missions, maritime security operations, coordinated mortar and artillery strikes, unit-level training, sniper training, battlefield trauma training, mine-clearing training, riot control, and combat marksmanship.

Hosted by Egypt, Operation Bright Star is another major exercise in which Kuwait is a participant. Conducted every two years, it has roughly similar purposes to Eager Lion in terms of promoting interoperability, exchanging expertise, and developing joint planning techniques. While Bright Star is significantly larger than Eager Lion (and is reportedly the largest multinational military exercise in the world), its training practices seem less intense or realistic — indeed, often planned and scripted to be as risk-averse as possible — and its U.S. participation is noticeably smaller, ranging from 200 to 800 soldiers in each exercise, compared to Eager Lion’s 3,700 American sailors and Marines.

3. Support for ongoing operations in theater such as Operation Inherent Resolve and Operation Spartan Shield with the help of stationed (or visiting) U.S. troops and prepositioned equipment in Kuwait. Units supporting Spartan Shield provide capabilities such as aviation, logistics, force protection and information management, and facilitate theater security cooperation activities like key leader engagements, joint exercises, conferences, symposia and humanitarian assistance/disaster response planning.

As he toured a U.S. Army Prepositioned Stocks-5 (APS-5) warehouse in Camp Arifjan on June 2, 2017, then-CENTCOM Commander Gen. Joseph Votel remarked on the importance of the prepositioned equipment in Kuwait to CENTCOM’s theater campaign planning. “The APS, along with sister programs in the other services, provides us a powerful and ready stock of equipment sets,” he said. “This flexibility is critical to staying ahead of a developing situation and is a crucial part of our planning process.”

Including Armored Brigade Combat Team, Infantry Brigade Combat Team, Sustainment Brigade, Fires Brigade, Medical Support Element, and Army Watercraft sets, all totaling more than $5.5 billion, the APS-5 is one of the largest sets of prepositioned ground-force equipment in the world (although those configurations are from 2017 and might have changed today). It provides CENTCOM with a high degree of operational flexibility to rapidly respond to a wide range of fast-developing and complex contingencies. Most of that equipment is what the U.S. military calls “configured for combat,” which means that it has high readiness levels and can be quickly used by deployed units in the field. In 2020, when Iran escalated its aggression against U.S. forces in the region in response to increased U.S. pressure, APS-5 was key to countering Tehran’s designs, said Lt. Col. Nichole Vild, the commander of Army Field Support Battalion-Kuwait.

The Next Level of Security Cooperation

Security cooperation between the United States and Kuwait is not limited to U.S. basing and the above-mentioned military activities and training exercises. Like other wealthy Gulf Arab nations, the Kuwaitis buy a healthy amount of weapons from the United States (though less than the Saudis or the Emiratis) using their own national funds to modernize their armed forces. The United States has roughly $20 billion in active foreign military sales (FMS) cases with Kuwait, with weapons ranging from ultra-modern fighter jets, attack helicopters, and anti-missile batteries to tanks, tactical missiles, and patrol boats. U.S. arms transfers to Kuwait are thus a significant part of security ties — though by no means bigger than the considerable U.S. military presence in the country, which provides reassurance to the Kuwaiti leadership like no other aspect of the relationship.

The Kuwaitis also send some of their military officers to study in the United States, but the numbers are modest — approximately 200 military personnel — compared to other Arab partners, such as Jordan, which has trained more than 6,000 members of its armed forces in U.S. military colleges (the Kuwaitis get one slot to West Point but don’t always fill it). It is also unclear how much effective training Kuwaiti students actually receive and use when they return home, a not uncommon phenomenon among other Arab partners, including Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.

In terms of bilateral political-military consultation, the United States maintains both a strategic dialogue and a Joint Military Commission (JMC) with Kuwait. The former, the fifth iteration of which concluded in January 2022, is an opportunity for senior U.S. and Kuwaiti officials to generally reaffirm their commitment to the bilateral relationship and to cooperation on peace and security in the region. The JMC, held in May 2022 for the 14th time, is more specific than the strategic dialogue, as it is used by senior U.S. and Kuwaiti defense officials (Washington has JMCs with other Arab partners too) to discuss U.S. military assistance.

The JMC is a useful instrument in the security relationship, as it deepens personal bonds and provides a roadmap for strengthening military ties, but it certainly has its limits, especially with partners like Kuwait that don’t rely on U.S. funding and are not recipients of U.S. Foreign Military Financing (FMF). Countries like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, and Kuwait will listen to U.S. advice on what American weapons to buy and how to pursue military modernization; but at the end of the day, it is their own money, and they have a sovereign right to use it in ways they think are most beneficial to their security interests. The promising thing about Kuwait is that it probably trusts and listens to the United States more than any other Arab partner. But still, Washington cannot impose its preferences on the Kuwaitis.

In summary, the security relationship between Kuwait and the United States is one of the strongest in the region. It is based on mutual, deep trust. Kuwait’s geographical location, wealth, modern military equipment, generosity, humility, and flexibility are huge assets for the U.S. government and the U.S. military. These are qualities and resources that are really hard to find (at least all of them together) in any international partner. That said, at a time when Washington is deemphasizing the Middle East, is the security arrangement between Kuwait and the United States sustainable? And more importantly, is the level of bilateral security cooperation good enough to ensure the defense of Kuwait for the long term?

This is an extremely important question that is not unique to Kuwait. Indeed, as I argued in Rebuilding Arab Defense, it applies to all the other Arab partners without a single exception. It is also a question that does not get enough treatment or attention in the Department of Defense. My own answer to that question is a firm no — it is definitely not enough for the United States and Kuwait to keep doing what they’re doing (as described above) and expect the security relationship to mature and cooperation to truly reach the next level. Thus, it is crucial to attain a position whereby Kuwait is better able to generate credible combat power and defend itself on its own and/or fight effectively with the United States should a mutual threat materialize.

Kuwait’s current military effectiveness is highly uncertain. I say uncertain, and not good or bad, because we can’t definitively judge what Kuwait is capable of, given that its armed forces haven’t been tested in any war or major contingency since they were quickly crushed by Saddam’s army in 1990. The Kuwaitis, unlike the Emiratis, also don’t have an expeditionary mindset and posture, which will make it even harder to see them in live action (not that that’s the goal). Per their Constitution, they won’t participate in a military conflict and engage in coalition operations unless it directly affects their national security.

We certainly have clues about Kuwait’s military effectiveness from the training and exercises its service members conduct regularly — by themselves, with the Americans, or with the British. Senior U.S. military officers currently serving in Kuwait attest that the Kuwaitis are “generally good with their U.S.-purchased equipment,” which, as previously mentioned, includes some of the best technologies the United States has both on land and in the air. Kuwaiti-owned Patriot missile defense batteries, for example, are well-oiled machines.

The Kuwaitis have a 2035 vision for their national defense. According to then-KAF Chief of the General Staff Lt. Gen. Mohammed al-Khadher, it has three phases: First, upgrading weapons across domains; second, recruiting, training, and investing in Kuwaiti youth for the future; and third, combining system integration and recruitment in the scope of training and exercises. Kuwaiti officials, led by Sheikh Nawaf al-Ahmad al-Jaber Al Sabah, who served as minister of defense multiple times over the years, began an aggressive push for military modernization shortly after the conclusion of Desert Storm. Namely, Kuwait purchased hundreds of U.S.-built M1A2 Abrams tanks, dozens of F/A-18 Hornet aircraft, and Hawk and Patriot anti-missile systems. Procurement, which continued throughout the 2000s but never addressed the needs of the Kuwaiti Navy, had to be intense because Iraqi forces had either destroyed or stolen much of Kuwait’s arms.

The Kuwaitis have invested heavily with their own money in the Udairi Range Complex to provide premier training for their armed forces on ground maneuver and ground gunnery. In 2017, the Kuwaiti Parliament approved a $10 billion budget to fund defense modernization until 2026. In 2021, it increased the budget of the Kuwaiti Ministry of Defense by 37% in real terms.

The Kuwaiti Air Force has some key ingredients to become a powerful force: relatively skilled pilots as well as modern equipment that has recently doubled in size and capabilities due to new acquisitions. The latter has included 28 Eurofighter Typhoon jets armed with sophisticated air-to-ground missiles and Storm Shadow standoff cruise missiles along with 28 U.S. Super Hornet Block 3 jets (to be delivered in 2023).

festival, in Kuwait City on Jan. 29, 2016. Photo by YASSER AL-ZAYYAT/AFP via Getty Images.

But again, we cannot truly measure the Kuwaiti Air Force’s potential, because it has not been tested in real combat since Desert Storm, when the Kuwaitis flew 18 to 24 sorties per day (in total they flew 780 sorties compared to the 6,852 of the Saudis) and only one of their Douglas A-4 Skyhawk fighters was lost to antiaircraft artillery fire during the war. Staying true to their low-profile, middle-ground foreign policy, the Kuwaitis did not participate in offensive operations against the Islamic State in OIR, but they did allow various OIR members to use their territory to launch air strikes against the terrorist group. At the beginning of the Saudi-led war in Yemen, the Kuwaitis contributed 15 fighter jets to the coalition, but it’s unclear if they actually bombed Houthi targets. One of the key constraints facing the Kuwaiti Air Force (which it can’t address) is its severe lack of aerial space to train, which means that Kuwaiti pilots can’t fully leverage their awesome fighter platforms that fly at supersonic speeds. Of course, there are mutually agreed upon training air spaces with neighbors; but there is no substitute for sovereign aerial training space.

The Kuwaiti Navy is quite small (it’s more of a coastal navy), constantly in need of better repair, maintenance, and recapitalization. Kuwaiti ships are old, but the sailors, according to a senior U.S. military officer in Kuwait as well as NAVCENT personnel, are proficient. They have assumed command roles on five different occasions in NAVCENT’s CTF 152 since 2010 and, as mentioned previously, are currently spearheading the Task Force.

In terms of human capital, most Kuwaitis don’t view the military as a serious career. It’s not difficult to get a job in Kuwait if you want to — at least for Kuwaiti citizens. Some pick the military, but many are not suited for it, so commanders end up having to weed out those who are not qualified or underperform, which is never easy to do due to cultural sensitivities and tribal politics (the same challenge exists in almost all other Arab countries). Because it’s such a small force, Kuwait, similar to several other Gulf Arab countries, relies on foreign recruits (from Bangladesh, for example), complicating military cohesion and command and control.

The Kuwaitis have some soft spots in their leadership corps but some bright stars too. The officer corps could be built upon. The non-commissioned officer (NCO) corps needs a lot of work and lacks empowerment, like all others in the Arab world; however, the Kuwaitis recognize this weakness. U.S. Maj. Gen. Patrick Hamilton and Kuwaiti Land Forces Commander Brig. Gen. Mohammad al-Dhafiri spoke in December 2020 about the importance of NCO training and exchanges, but it’s unclear what came out of that conversation. KAF Commander Lt. Gen. Khaled Saleh Al Sabah is a tremendous national asset. Trained at Sandhurst, in the United Kingdom, he is Kuwait’s best soldier, groomed by the Kuwaitis for years. He’s a dynamic individual with limitless passion and impressive oratory skills. He exhibits natural leadership traits and knows how to fire up his soldiers.

Kuwait has a single military university for all the Kuwaiti services called Ali Al Sabah Military College. Founded in 1968, it is one of the oldest military colleges in the region. Most senior Kuwaiti officers attend it, and the training lasts one year (high school graduates study for three years). The college’s emphasis, unsurprisingly, is on the Kuwaiti Land Forces. All the Kuwaiti Navy students study abroad while some Kuwait Air Force students study in Kuwait. Military service was compulsory in Kuwait from 1980 to 2001, then legislation in 2017 reintroduced it, requiring Kuwaiti men aged 18-35 to serve for one year. They are also required to be in the reserve forces until the age of 45. Yet in 2017, it was reported that half of the 2,300 Kuwaiti men eligible for military service failed to register. In December 2021, the Kuwaiti military for the first time started accepting applications from women for non-combat roles — a decision that was less than popular among the relatively numerous more conservative members of Kuwaiti society.

All of this data remains vastly insufficient to comprehensively assess the KAF. The Kuwaitis don’t fully know their strengths and weaknesses, nor do the Americans, because they haven’t gone to battle for a very long time. They also don’t “task-organize” for combat, which means they don’t group their forces in a certain way to accomplish a particular mission; nor do they allocate available assets to subordinate commanders and establish their command and support relationships.

While it is difficult to analyze Kuwait’s military effectiveness, it is possible to assess the country’s defense institutional capacity — in other words, the strategic, institutional, organizational, and programmatic fabric of its national defense establishment. That’s quite a useful and necessary exercise because there’s an important, if not direct, relationship between how a country is postured in peacetime and how it fights during wartime. It’s not exactly a novel proposition, but it’s remarkable how it is often overlooked in military analyses: the better prepared you are for war, more often than not, the better you will perform on the battlefield.

The fact that Kuwait has demonstrable deficiencies in its defense foundation gives a strong hint that the country’s warfighting capabilities may be less than reliable. Kuwait, like almost all other Arab partners of the United States, does not properly invest in Phase Zero, which consists of activities meant to favorably shape the environment through better training, readiness, and management of national defense. In other words, proper defense governance for the Kuwaitis is not a priority.

Why does Kuwait’s, or any other Arab partner’s, defense institutional capacity matter for Washington? Because, at the very least, it allows Kuwait to better utilize and sustain U.S. military assistance. It puts the country in a better position to build military capability the right way, a process that itself has an effect on the respective state’s ability to conduct more effective military operations. A stronger Kuwait that can participate in joint, combined operations with the United States and possibly others in a coalition is naturally a more attractive and valuable partner for Washington. That is what U.S. security cooperation’s ultimate goal and prize should be (which is hardly ever attained in the Middle East): not just access and basing for the U.S. military (though incredibly important enablers) but also helping the partner develop powerful and sustainable military capabilities so it can fight together with the United States in pursuit of shared objectives and common security interests.

Defense institution building is conducted at multiple levels, including the ministerial, joint or general staff, and military service headquarters levels, and it can target numerous functions, including defense resource management, human resource management, logistics, acquisition, and rule of law. Unlike my Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Lebanon, and UAE case studies in Rebuilding Arab Defense, which were more or less comprehensive, my assessment of Kuwait’s defense institutional capacity is limited to the elements of policy, strategy, and planning, which I believe are the key pillars of this entire military developmental process. Indeed, it all starts, or should start, with a national security policy that generally covers ends (what needs to be achieved) as well as ways and means (how and with what resources those ends are to be achieved). The strategy refers to the main elements that are needed to pursue the policy, while planning consists of the concrete steps that must be taken incrementally to achieve the elements of the strategy.

The good news is that, unlike several other Arab partners, Kuwait has an official National Military Strategy. The bad news is that it’s not very useful, not because of what it says but because of what it doesn’t say. The bottom line, and the emphasis, of the strategy is that Kuwait, in addition to its ability to operate unilaterally to defend the country per article 47 of the Constitution, will respond to threats mainly coming from Iran, regional militias loyal to Tehran, and Sunni terrorist groups with the help of partners. There is nothing wrong with leveraging the capabilities of your close friends. As a member of the Gulf Cooperation Council since its founding in 1981, it is very much expected that Kuwait would lean on this group of neighbors to contribute to its protection (though this approach clearly didn’t work when Saddam effortlessly rolled his tanks into Kuwait and occupied the country).

The problem with that approach is that Kuwait’s own military preparedness, readiness, and organizational approach to a potential war in the region (most likely with Iran) considerably lags behind most of its Gulf Arab partners as well as its main regional adversary — Iran, along with its Shi’ite agents in Kuwait and militant allies in Iraq.

While a couple of other Gulf Arab militaries have gradually moved to the Force Provider/Joint Warfighter model, Kuwait prepares for and organizes its defense largely like it did in 1990, before Iraqi forces invaded. Kuwait’s current approach to steady-state operations leans almost exclusively on U.S. protection and involvement. In Phase Zero, this is not a sustainable approach for effectively and efficiently countering the increasingly complex security challenges and threats in the region.

While Kuwait has continued to equip itself in the last two decades with modern U.S. weapons systems, its ability to employ and sustain these weapons to actively defend Kuwait has not kept pace with its acquisitions. Former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld once said to American soldiers whose vehicles were getting blown up by Iraqi insurgents’ improvised explosive devices that “you go to war with the army you have — not the army you might wish to have.” Fair enough, but let me tweak that a little bit, and tie it to Kuwait’s (and other Arab partners’) acquisition mess: “you go to war with the army you have; and if you bought the wrong army, that’s your fault!”

This in a nutshell is the story of all of America’s Arab partners when it comes to purchasing arms. First, they buy the equipment, then they try to see (some even don’t bother) how it fits into their defense strategies and war plans (assuming those exist) and how it can be used in joint operations, when it should be the other way around. What no Arab partner does, including Kuwait, is create a resourcing system that rewards jointness.

There’s very little joint training among the Kuwaiti services, even though there is a joint staff in the Ministry of Defense all working under KAF Commander Lt. Gen. Khaled Saleh Al Sabah, who is also the chief of the General Staff — meaning he doesn’t just have command responsibilities but also organize-train-and-equip responsibilities (he’s the equivalent of the U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff). The Kuwaitis are currently seeking to build a Pentagon-like facility to group all their service headquarters in one place (they have been dispersed all this time), which is smart. If you want to be a joint force, at the very least you have to be in the same building. The Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) currently has an FMS case with Kuwait worth $1 billion to design and construct a new Kuwaiti Ministry of Defense Headquarters Complex that includes over 20 facilities for both civilian and military leadership.

The US Role

As Washington prioritizes the Indo-Pacific, with the attendant military drawdown this causes in the Middle East, it is critical that the security arrangement between the United States and Kuwait is reconfigured and the latter’s approach to Phase Zero rises to meet the Iran-centric threat. For both its own defense and the general security of the region, Kuwait must improve its ability to generate credible combat power and defend itself on its own or in a combined effort with the United States should a mutual threat materialize.

However, the Kuwaitis are unable on their own to engage in effective defense institution building. The United States, and especially CENTCOM, have a major role to play in this process as they have a moral and strategic responsibility to leverage the more than three decades of cooperation amassed since the First Gulf War. There’s a lot of good to work with and build upon in Kuwait, be it competent personnel or modern equipment. What the United States needs to do is help the Kuwaitis organize — or better yet, help them task-organize. The defense of Kuwait, now and into the future, will benefit not from more weapons but from improving how Kuwait organizes its command structures into a modern system supporting enhanced joint force employment of its military capabilities.

Among the structural defense reforms Kuwait should pursue is the formulation and operationalization of a capstone document that defines the missions of the KAF, specifies the country’s joint warfighting concept, and plans and allocates forces for steady-state operations. This document would create a “north star” for Kuwait’s daily operational planning with CENTCOM and future capability-based resource planning with the Pentagon’s DSCA, much like the Unified Command Plan, Contingency Planning Guidance, and Global Force Management Process do for the United States.

Kuwait’s ability to fight — and fight jointly — is vital not only for the country’s defense but also for CENTCOM’s theater plans. While CENTCOM does have a contingency plan for each of its partners in the region — in other words, a plan to repel or defend against a major Iranian threat — this plan would benefit tremendously from direct and tangible contributions from the regional partners, including Kuwait. If Kuwait is not doing much in steady-state operations — and it appears it isn’t, with the exception of buying equipment — then chances are its contributions during wartime to a coalition fight will be negligible at best.

To remedy this status quo, the Kuwaiti military must establish two standing joint force commands with two joint force commanders, each responsible directly to the Kuwaiti National Command Authority for executing Kuwait’s critical defense missions: one in the eastern part of the Gulf in the littoral areas and territorial waters of the country, and one across the northwestern land borders with Iraq.

Kuwaiti service commanders, along with members of the Kuwaiti National Guard, would provide their best officers for assignment to these standing joint force commands. Joint force commanders and staffs, reporting to and working under the close supervision of KAF Commander Lt. Gen. Khaled Saleh Al Sabah, would be tasked with conducting joint operational planning for steady-state operations and exercises to ensure higher levels of joint operational readiness. These joint operational plans would, among other things, describe the threat and operational environments and how (the ways) military capabilities/the joint force (the means) are used in time and space to achieve operational objectives (the ends). Efforts to pursue other structural defense reforms — including human resource management, defense resource management, logistics, and rule of law — should follow once the operational shortfalls have been addressed.

celebrate their victory over the Iraqi army on Feb. 27, 1991, in

Kuwait City. Photo by CHRISTOPHE SIMON/AFP via Getty

Images.

We must recognize that this is a sensitive moment and perhaps even an inflection point in U.S.-Arab security relations. While other Gulf Arab partners are vastly unsure about America’s security commitment and are in the midst of figuring out how they are going to defend themselves against Iranian aggression — on their own or with the help of others, possibly including the Chinese and the Russians — Kuwait still has faith in U.S. protectorship. But we should not take this continued support for granted. We have to remember that anyone less than 30 years old in Kuwait was born after the 1991 liberation. There’s a concern that the young Kuwaiti workforce may not see the United States in the same way as those that lived through Desert Storm. Statistically, this is supported by polls that show Kuwaitis with a favorable view of the United States dropping from 36% in 2001 to 17% in 2006. The numbers went back up in later years but not by much. Asked in 2019 if they consider relations with the United States to be “very important,” only 27% said yes.

We must reward and nurture Kuwait’s faith in the United States by making things right for both of us. We have a unique opportunity in Kuwait to show the Kuwaitis and all other Arab partners that it is indeed possible to build a new and more effective model for security cooperation that serves mutual interests. We don’t need two divisions of tanks stationed in Kuwait, just like we don’t need a brigade combat team and two fighter squadrons in the country. The Kuwaitis have enough firepower of their own. What we need is tailored and more consistent U.S. advice on defense governance and, specifically, on how to create a Kuwaiti joint force by instituting the above-mentioned command structures and practices.

About the Author

Bilal Y. Saab is Senior Fellow and Director of the Defense and Security Program at the Middle East Institute. He is a political-military analyst on the Middle East and U.S. policy toward the region. He specializes in the Levant and the Gulf and focuses on security cooperation between the United States and its regional partners, and national security and defense processes in Arab partner countries. He is the author of Rebuilding Arab Defense: U.S. Security Cooperation in the Middle East (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, May 2022). Saab is an Adjunct Assistant Professor at Georgetown University’s Security Studies Program in the School of Foreign Service, teaching graduate courses on U.S. defense policy in the Middle East and international security studies. Prior to MEI, Saab served as Senior Advisor for Security Cooperation (SC) in the Pentagon’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, with oversight responsibilities for CENTCOM. In his capacity as the Department of Defense’s lead on security cooperation in the broader Middle East, Saab supported the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy’s responsibility for SC oversight by leading prioritization and strategic integration of SC resources and activities for the CENTCOM Area of Responsibility.

Acknowledgements

I would very much like to thank three individuals for speaking with me off the record and sharing their insights and expertise while I was conducting research for this paper. They are U.S. Air Force Brig. Gen. Darrin E. Slaten, currently serving as Chief of the Office of Military Cooperation and Senior Defense Official/Defense Attaché in Kuwait; Army Gen. (ret.) Michael X. Garrett, former ARCENT Commander; and Army Col. (ret.) Bryan Hilferty, Strategic Communications Advisor with ARCENT/Coalition Forces Land Component Command. In addition, I owe a debt of gratitude to Kevin Donegan, Leena Khan, Michael Nagata, Sanam Vakil, and Joseph Votel for reviewing the paper and providing me with excellent feedback.

Additional Photos

Main photo: The final section of the last American military convoy to depart Iraq from the 3rd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division crosses over the border into Kuwait on Dec. 18, 2011, in Khabari Al Awazeem, Kuwait. Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images.

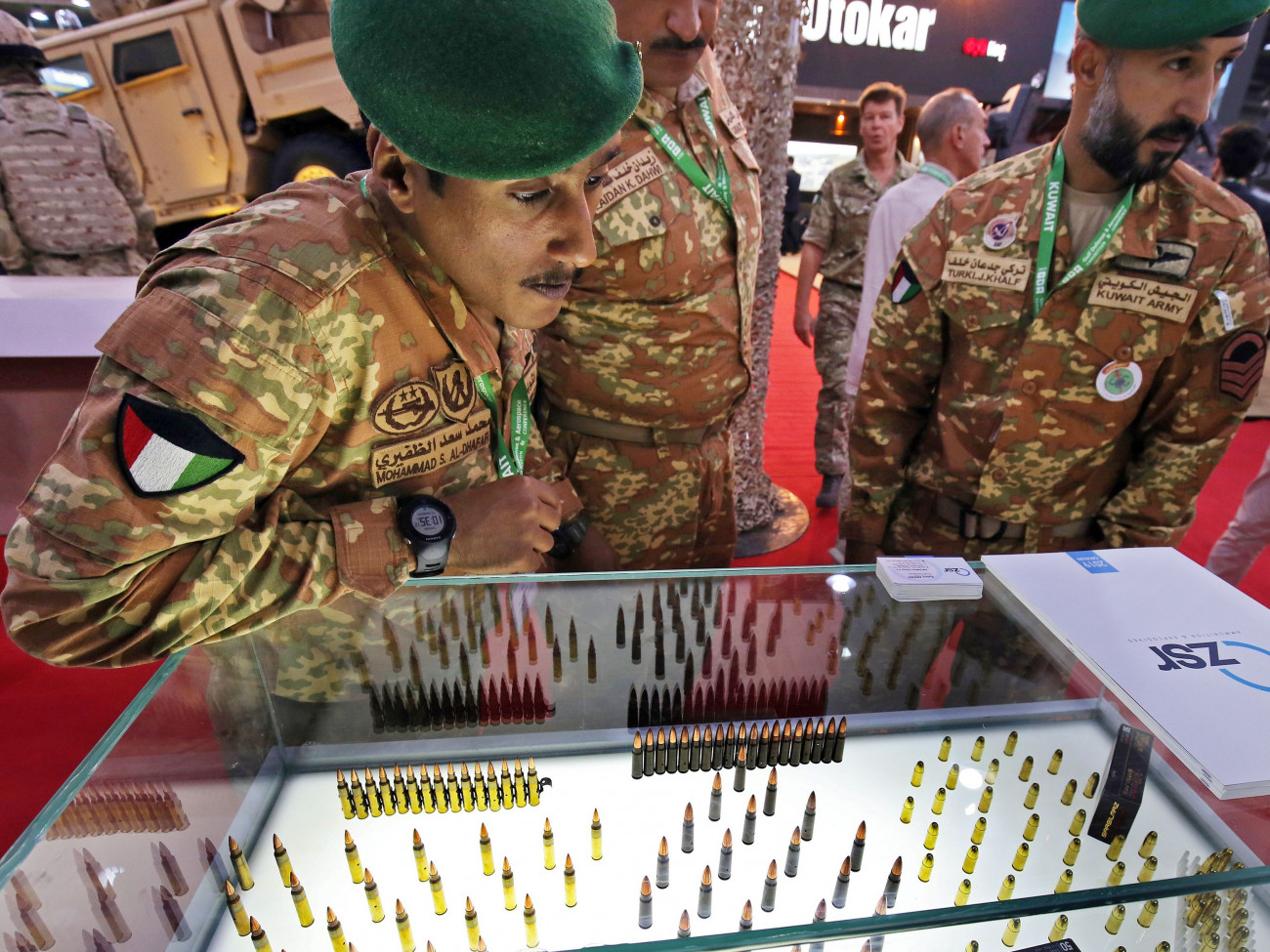

Contents photo: Members of the Kuwaiti military gather around a bullet display at the Fifth Gulf Defence and Aerospace exhibition (GDA) in Kuwait City on Dec. 10, 2019. Photo by YASSER AL-ZAYYAT/AFP via Getty Images.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.