The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed a number of weaknesses in government response, including a fragmentation of the decision-making process, inadequate consultation with experts, opacity of epidemiological data, as well as a lack of health care capacity, collective action, and general preparedness. Perhaps above all though, the pandemic has highlighted the inadequacy of communication with the public and their lack of involvement in the decision-making process.1 While the novel coronavirus caught all governments by surprise, some governments, especially those that enjoy high levels of trust (and not necessarily the wealthiest ones), have fared better than others.2 This has prompted some countries to hold public hearings to gain more insight into decision-making during the pandemic and rebuild trust in institutions.

Strikingly but unsurprisingly, no country in the Arab world has yet called for a public inquiry into COVID-19. While this is even more relevant for countries that have traditionally enjoyed democratic governance (Tunisia, Lebanon, and Kuwait) and for countries that have suffered disproportionately from the pandemic (Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, and Tunisia), this exercise could be useful for all Arab countries in regaining the trust needed to better respond to future crises.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic is far from over, this article aims to launch a conversation on the need for instituting public hearings on how the pandemic has been handled in the Arab world on both the health and socioeconomic levels. Public hearings are a key tool of government oversight and accountability. Even if they are sometimes politicized, if conducted properly they can help citizens better understand the decisions that were made, and above all draw important lessons for the future.

COVID-19 public hearings around the world

France was the first country to open inquiries into how the pandemic was handled. In June 2020, two months after France entered its first national lockdown, the Paris chief prosecutor launched a preliminary inquiry into “possible criminal offenses” by decision-makers.3 Made up of 32 MPs from across the political spectrum, the inquiry is historic in that, for the first time, it is taking place in the midst of a crisis, as opposed to afterwards. On Sept. 10, 2021, Agnes Buzin, the former minister of health who was in charge of the initial pandemic response, was charged by a special court for minimizing the public health danger that the novel coronavirus posed and “endangering the lives of others.”4 Buzin is yet to appear in court to explain her ministry’s lack of preparedness.

Brazil also set up an official congressional investigation, known as the “CPI da COVID-19,” to investigate the government’s “negligence” in managing the crisis.5 The country has registered, as of Dec. 6, 2021, more than 615,744 deaths from the virus, trailing only the United States in terms of the absolute number of deaths.6 The CPI [Comissão Parlamentar de Inquérito] has cast the Brazilian government’s response as woefully inept and endangering the lives of citizens: the president supported discredited remedies; the government ignored dozens of emails regarding vaccine supply, which resulted in delays in the purchase of vaccines; and many members espoused unscientific solutions to the pandemic.7

After much reluctance, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson said that the public inquiry into his government’s handling of the pandemic would be held within the next year.8 And before the recent surge of COVID-19 cases caused by the Delta variant, there were widespread calls from members of the U.S. Congress as well as experts to have a public inquiry into the U.S. government’s handling of the crisis.9

Performance in the Arab world

Despite the absence of calls for similar public inquiries in the Arab world, the way governments in the region have handled the COVID-19 crisis has been mixed. Some, like the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, have done far better than others, both on the economic and health fronts. The UAE arguably had the financial means to purchase vaccines not only en masse but way in advance, efficient and high-quality health infrastructure, and above all the trust of its citizens, which correlates with better performance in the pandemic.10 Other states, especially those witnessing compounding crises such as economic turmoil (like Iraq, Tunisia, or Lebanon) or war (such as Yemen or Syria), have fared poorly with higher deaths rates and collapsed health care systems.11 In between these two extremes is a group of countries with medium levels of trust in government — Algeria, Jordan, and Morocco — that managed the pandemic through what could be called a “knee-jerk reaction” approach to avoid protests and social unrest.12

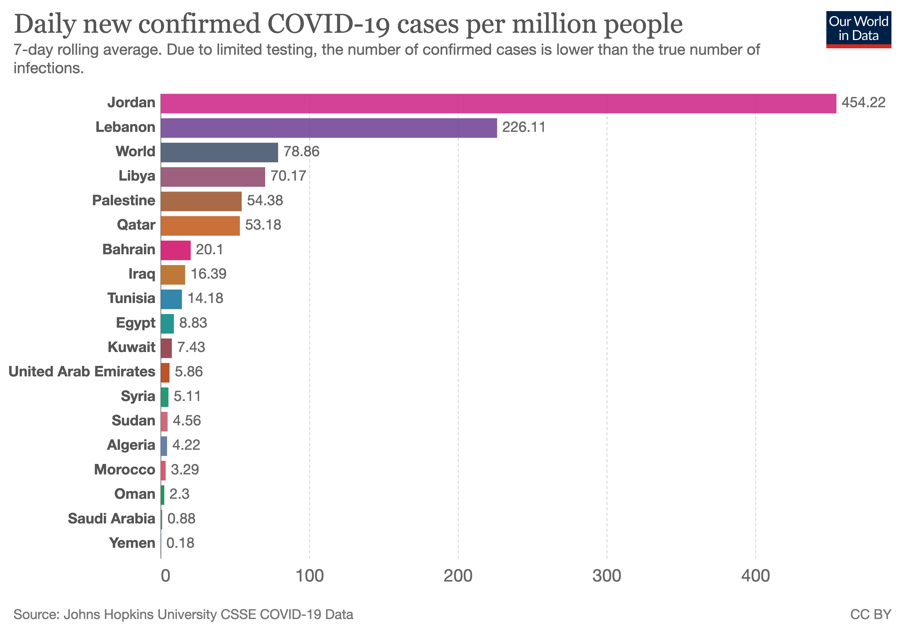

The situation remains critical in countries with low levels of trust in government. Jordan and Lebanon are still registering more cases than the world average (figure 1). And although the numbers in Iraq and Tunisia have improved, these countries are still recording four to 20 times more cases than the GCC countries.

Figure 1: Daily new confirmed COVID-19 cases per million people

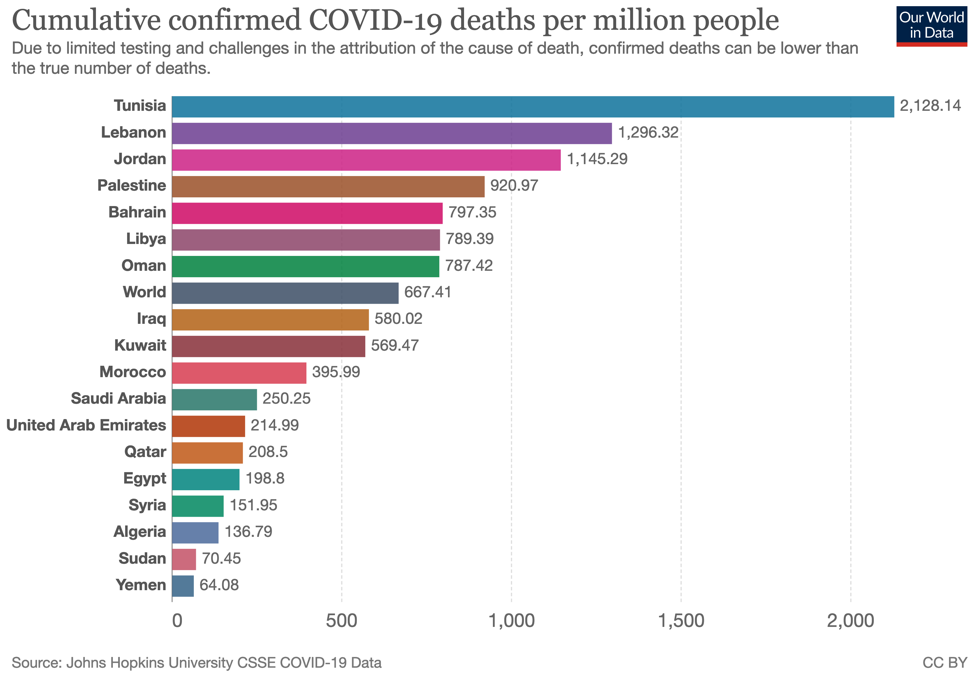

Perhaps the most telling indicator of how poorly the COVID-19 crisis has been managed in the Arab world is the total number of deaths per million (figure 2), which in many cases is far higher than the global average. The situation is especially dire in a handful of countries, notably Tunisia with 2,128.14 deaths per million (3.2 times the world average), Lebanon (1,296.32 deaths per million or twice the world average), and Jordan (1,145.29 deaths per million or 1.7 times the world average).

Figure 2: Cumulative confirmed COVID-19 deaths per million people

There are of course a few interrelated caveats when interpreting these graphs. The first is that many of these countries do not have reliable institutions. Second, their testing capacity remains inadequate. Furthermore, the pandemic has been extremely politicized, with lack of transparency and underreporting regarding the official numbers of infections and deaths (notably in Egypt).13

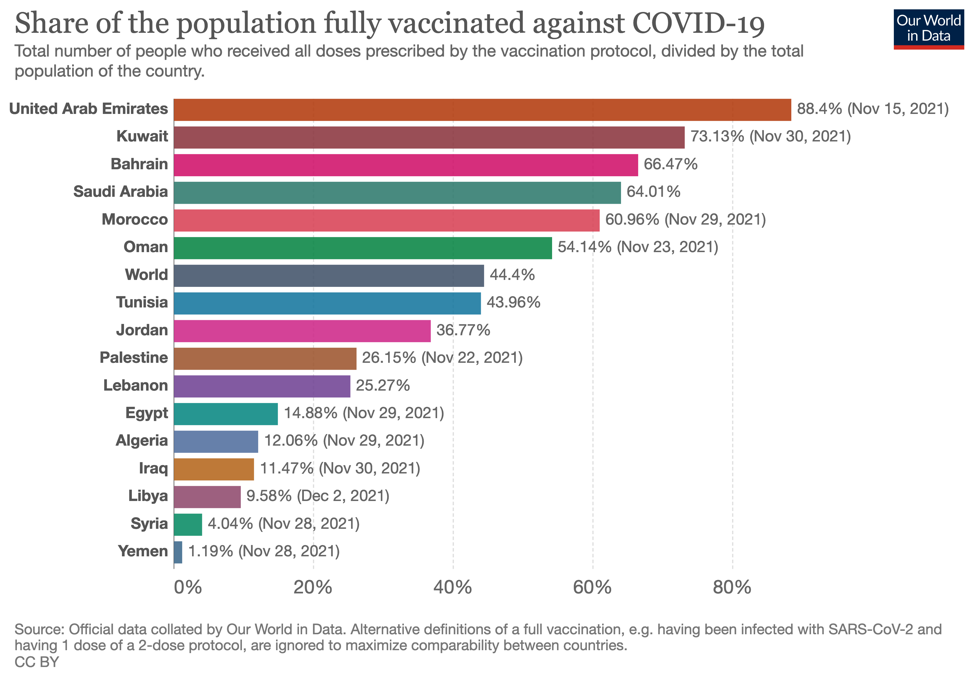

Despite these caveats, citizens have been keen to express their disapproval of their governments’ inadequate responses. The ratings for Lebanon and Tunisia are the lowest in the region, both in terms of the government’s COVID-19 response (16% Lebanon, 31% Tunisia) and its economic performance (1% Lebanon, 13% in Tunisia).14 By contrast, Morocco has performed best; despite stringent public health measures, its citizens seem to be content with the government’s health and economic responses (86% and 56% respectively). And indeed, after a very slow start, Morocco has also done pretty well in terms of vaccination rates: It is the only non-GCC country to have fully vaccinated more than 50% of its population (figure 3). On the economic front too, Morocco put in place several measures to offset the economic impact of COVID.15

Figure 3: Share of people fully vaccinated against COVID-19

But it is Lebanon that is perhaps the best example of why public inquiries are critical. It has one of the lowest vaccination rates in the region — way below the world average (figure 3) — and the second highest total number of deaths after Tunisia (figure 2). And yet despite these poor outcomes, the outgoing government recently lauded its response to the pandemic.16 Such apologist behaviors can end up distorting the narrative. This is precisely why public inquiries are so vital: Even if they do not end up sanctioning any government officials, at least they set the record straight.

Dr. Joelle M. Abi-Rached is currently Lecturer in History of Science at Harvard University as well as an Associate Researcher at the Paris Institute of Political Studies. The views expressed in this piece are her own.

Photo by THOMAS SAMSON/AFP via Getty Images

Endnotes

- For more see, Norheim, O. F. et al. 2021. “Difficult Trade-Offs in Response to COVID-19: The Case for Open and Inclusive Decision Making.” Nature Medicine, 27(1): 10–13, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-01204-6.

- For the Arab world see, Diwan, I. and J. M. Abi-Rached. 2020. “Covid-19, Trust and Rising Economic Challenges in the Arab World.” Economic Research Forum (ERF) (blog), December 20, 2020, https://theforum.erf.org.eg/2020/12/20/covid-19-trust-rising-economic-c…. More generally on the role of trust in government during Covid-19, see: Abi-Rached, J. M. and I. Diwan. 2021. “Governing Life and the Economy: Exploring the Role of Trust in the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Erasmus Journal for Philosophy and Economics, 14(1): 71-88-71–88, https://doi.org/10.23941/ejpe.v14i1.580.

- “Paris Probes Possible ‘criminal Offences’ during State’s Handling of Covid-19,” RFI, June 16, 2020. https://www.rfi.fr/en/france/20200610-paris-probes-possible-criminal-of….

- Agence France Presse. 2021. “France’s Former Health Minister Charged over Handling of Covid Crisis.” The Guardian, September 10, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/sep/10/frances-former-health-min…; Le Monde and Agence France Presse. 2021. “Covid-19 : Agnès Buzyn mise en examen pour « mise en danger de la vie d’autrui » pour sa gestion de l’épidémie,” Le Monde, September 10, 2021. https://www.lemonde.fr/police-justice/article/2021/09/10/covid-19-agnes….

- Milhorance, F. 2021. “Brazil’s Inquiry into Covid Disaster Suggests Bolsonaro Committed ‘Crimes against Life.’” The Guardian, June 25, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/jun/25/brazil-coron…; and “Brazil COVID-19 Crisis: Inquiry Uncovers Government Negligence,” NPR, June 27, 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/06/27/1010760855/brazil-covid-19-crisis-inquir….

- Our World in Data, December 6, 2021.

- Harris, B. 2021. “Brazil’s Covid Inquiry Puts Bolsonaro on the Back Foot.” Financial Times, June 17, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/499bdf96-622a-4c14-8e91-faf4989f0113.

- Payne, S. 2021. “Johnson Says Covid Public Inquiry to Start within a Year.” Financial Times, May 11, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/e32b6227-89af-4faf-8e38-1c18ca213eb0.

- Galston, W. A. 2020. “Appoint a Coronavirus 9/11 Commission.” Wall Street Journal, March 31, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/appoint-a-coronavirus-9-11-commission-1158…; and Ward, A. 2020. “The US Needs a 9/11 Commission for the Coronavirus.” Vox, April 3, 2020, https://www.vox.com/2020/4/3/21206135/coronavirus-covid-9-11-commission….

- For more see, Abi-Rached and Diwan, “Governing Life and the Economy: Exploring the Role of Trust in the Covid-19 Pandemic,” and Diwan and Abi-Rached, “Covid-19, Trust and Rising Economic Challenges in the Arab World.”

- Diwan and Abi-Rached, “Covid-19, Trust and Rising Economic Challenges in the Arab World”; and “COVID-19 Crisis Response in MENA Countries.” OECD, November 6, 2020. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-crisis-respo….

- This is best illustrated in Jordan, when the country's health minister had to resign after six patients died of Covid-19 due to a shortage in oxygen at the hospital, see “Covid: Jordan’s Health Minister Quits over Hospital Oxygen Deaths.” BBC News, March 13, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-56381870. For Algeria, see: Serrano, F. 2020. “In Algeria, Protests Pause for COVID-19 as the Regime Steps Up Repression.” World Politics Review, August 31, 2020. https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/29028/in-algeria-protests-…; and for Egypt, see: “Egypt: Covid-19 Cover for New Repressive Powers,” Human Rights Watch, May 7, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/07/egypt-covid-19-cover-new-repressive….

- “As More Virus Cases Trace Their Origins to Egypt, Questions Rise over Government Measures,” Washington Post, accessed November 14, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/as-more-virus-cases-trace-their-or….

- Al-Shami, “COVID-19 in the Middle East and North Africa – Arab Barometer,” accessed September 25, 2021, https://www.arabbarometer.org/publication/covid-19-in-the-middle-east-a….

- Abouzzohour, Y. 2020. “Coping with COVID-19’s Cost: The Example of Morocco,” Brookings (blog), December 23, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/research/coping-with-covid-19s-cost-the-examp….

- In a series of self-congratulatory tweets on August 28, 2021, Petra Khoury, medical adviser to the outgoing Prime Minister Hassan Diab, wrote that if Lebanon had averted a lethal death surge due to the Delta variant, it is because of the wide immunity acquired in the population (though the evidence lacks) as well as the vaccine coverage, one of the lowest in the region at 20%.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.