This piece is part of the series “All About China”—a journey into the history and diverse culture of China through short articles that shed light on the lasting imprint of China’s past encounters with the Islamic world as well as an exploration of the increasingly vibrant and complex dynamics of contemporary Sino-Middle Eastern relations. Read more ...

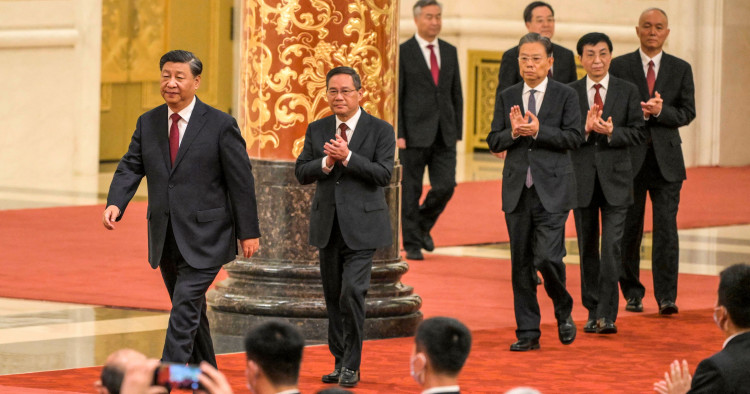

The recently concluded 20th Party Congress was China’s most consequential political event in decades, as Xi Jinping secured an historic third term as CCP General Secretary and a Politburo Standing Committee stacked with his allies and protégés. But Xi has closed out his second term with the country registering a disappointing economic performance.[1] China is on pace to fall well short of the official growth rate target of 5.5% for this year,[2] and Beijing’s reliance on a large amount of non-productive investment to drive economic growth might be reaching its limits.[3]

The economic headwinds that China faces at home and abroad are a political problem for Xi, whose party’s legitimacy has been built upon rapid growth and rising incomes. They are also a concern for the international community, which had become accustomed to China being the global economy’s growth engine. Clearly, this is so among the countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), whose engagement with China has grown exponentially in recent years.

Domestic Economic Headwinds and External Challenges

After a strong start in early 2022, China’s economy has slowed markedly. The World Bank recently slashed its forecast for Chinese GDP growth to 2.8% this year, after the 8.1% rebound in 2021.[4] Although China said its economy expanded by 3.9% in the third quarter of 2022, the country remains on pace to miss its official full-year target by a wide margin.[5] This downturn is the result of the compounded challenges of COVID-19 lockdowns, a regulatory crackdown, and the economic effects of extreme weather events. The slump is also occurring amid a bruising trade war with the United States and setbacks for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

China’s zero-COVID strategy has stifled economic activity. Multiple outbreaks of the Omicron variant of COVID-19 and associated mobility restrictions in several Chinese cities, including manufacturing hubs such as Shenzhen and Tianjin, have disrupted economic activity across industries, reduced investor confidence, suppressed consumer spending, and led to food and medicine shortages.[6] Yet, there is no sign that Xi plans to reverse course.[7] On the contrary, state media continue to depict the zero-COVID approach not as a public health policy but as a “struggle of material and spirit” and “a contest of strength and will.”[8]

China’s overleveraged property market is in crisis. New home sales in major cities have plummeted, property prices have slumped, a slew of developers have defaulted and issued profit warnings, and households have stopped servicing mortgages for unfinished units. Weak real estate activity and negative sentiment in the housing sector is at the heart of China’s economic troubles as property and other industries that contribute to it account for up to a quarter of China’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).[9] Although Chinese authorities have intervened to try to rein in the real estate industry’s soaring debt, they continue to search for ways to prevent the crisis from spreading to other areas of the economy.[10]

The Chinese authorities’ regulatory clampdown on Big Tech and other private industries has taken a bite out of the economy.[11] Since late 2020, Beijing has waged a multi-pronged campaign to strengthen regulatory control over various businesses and industries, most notably the technology sector.[12] Different reasons were used to rein in tech companies, ranging from the need to combat alleged monopolistic behavior, to that of addressing data security concerns, financial risk, marketing deception, and worker exploitation. The clampdown on tech giants’ activities was also connected to President Xi’s “common prosperity” campaign to close the wealth gap.[13]

However, the enforcement of strict regulations on its tech platforms — compounded by coronavirus lockdowns and trade sanctions — disrupted financial markets; wiped billions of dollars of value from Chinese tech titans such as Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, Didi Chuxing, and Meituan; spooked overseas investors; and in some cases led to large-scale layoffs.[14] Although in recent months Beijing has taken less draconian regulatory action against tech giants,[15] it is not clear that this softening at the edges will persist or that the Chinese tech sector will be able to reclaim its growth momentum.

The effects of extreme weather conditions are weighing on the Chinese economy. This past summer’s crippling heat wave and drought,[16] exacerbated by climate change, caused river and freshwater lake levels to plunge. The resulting reduction of hydropower generation led to the shutdown of China’s southeastern industrial and export hubs. In addition, thousands of acres of crops in Sichuan and Hebei provinces were damaged.[17] These recent weather events and their adverse economic impacts provide evidence of the potential danger that lies ahead for China, a country that is highly exposed to various climate-related hazard risks.[18]

The cooling of the Chinese economy is occurring amid a bruising trade war with the United States and faltering export demand.[19] The initial tariffs-focused trade war struck a blow to Chinese exports to the United States. Since then, US export controls and import restrictions have tightened.[20] The latest such efforts put a block on the shipment to China of all semiconductor chips and equipment for making chips for artificial intelligence (AI) and high-performance computing (HPC) without an export license.[21] A recent political risk survey found that 79% of respondents expect the intensified US-China competition will be accompanied by a trend toward greater economic decoupling, accelerating the departure of these firms from China.[22] Meanwhile, overseas demand for Chinese exports has weakened, as the US, European, and other markets struggle with rising inflation and interest rates.[23]

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the country’s most significant geopolitical tool for enhancing its soft power and carrying out its ambitions, is facing multiple challenges. The luster has come off the BRI due to delayed or distressed projects, though, to be fair, Beijing has taken practical measures to address design and implementation concerns[24] and has also become open to accepting some losses on loans and renegotiating debt.[25] Even so, the BRI is beset by the deterioration of economic conditions in partner countries and flagging demand for projects in traditional Belt and Road sectors owing to fiscal constraints[26] while the US and Europe have launched alternative infrastructure financing initiatives.[27]

In the face of these challenges, references to the Belt and Road Initiative in Chinese leaders’ speeches have become less frequent, while the Global Development Initiative (GDI) appears to have become the new trending term in Chinese official discourse.[28] Still, there is no sign that the Chinese leadership is about to abandon the BRI — or that it will fade into irrelevance.[29] Instead, a recalibration process underway,[30] with Chinese officials exploring how to make the BRI more sustainable[31] — a course correction that is likely to entail more rigorous evaluation of new financing, slower expansion, and smaller-scale projects in the health, green, and digital sectors.

Implications for China’s Middle East Engagement

China’s growth slowdown is reverberating globally. Its ripple effects are impacting different regions and the countries within them in different ways. To date, the impact on Chinese engagement with the Middle East has been decidedly mixed, as can be seen in China’s diplomatic interactions, energy relations with oil producers, and BRI partnerships.

China’s zero-COVID policy has disrupted but not stifled its diplomatic engagement with MENA countries. The year began with a flurry of visits and announcements. In early January, the foreign ministers of Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Oman, as well as GCC Secretary-General Nayef Falah M. Al-Hajraf traveled to China for meetings aimed at deepening relations,[32] followed several days later by the arrival in Beijing of Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian to launch the 25-year bilateral Comprehensive Strategic Agreement (CSA) signed in 2021.[33]

Since then, however, visits by high-ranking officials and delegations to and from the region and splashy breakthroughs have tapered off. Except for the limited number of travels to the region and talks with resident diplomats by PRC Special Envoy to the Middle East Zhai Jun,[34] most other meetings at the ministerial and sub-ministerial levels have been conducted virtually.

It is difficult to determine when “normal” Chinese diplomatic interaction with the region will resume given Beijing’s ongoing anti-covid travel restrictions. Xi’s state visit to Kazakhstan and participation in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in Uzbekistan in mid-September — his first trip abroad since the onset of the pandemic — did not in itself signal the return to the pre-pandemic norms of in-person diplomacy. Yet, immediately upon the conclusion of the 20th Party Congress, visits scheduled for the coming weeks by several foreign leaders to China in the coming weeks were confirmed,[35] and Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan announced that President Xi is expected to visit the kingdom “in the near future.”[36] The exact date and the details of Xi’s widely anticipated visit have yet to be disclosed. However, when the visit does occur, it is likely to coincide with the holding of the China-Arab and China-GCC summits, which will serve as a reminder of the importance both sides attach to the extensive ties they have developed and the fact that the transformation of China-MENA relations has largely occurred during Xi’s tenure.

It is noteworthy that cooperation in the oil sector, which forms the bedrock of China-Middle East ties, remains strong despite the disruption of in-person diplomacy, the economic headwinds facing China, and challenging energy market conditions. To be sure, Beijing’s COVID lockdowns have depressed domestic demand for oil in China, where transport accounts for about half the country’s oil consumption.[37] In fact, China’s oil imports for the first three-quarters of this year were 4.3% lower than the same period last year.[38] Moreover, since the war in Ukraine began, China has boosted imports of steeply discounted Russian crude oil. But China still obtains nearly half its imported oil from the MENA region. Saudi Arabia is still China’s top supplier. And China is still the leading customer for Gulf Arab oil producers and for Iran.[39]

Weak Chinese oil demand would ordinarily spell bad news for Middle East producers, except that at this juncture, by providing some relief to a world battling stubbornly high inflation, it might help avert a global recession, which would be far worse. On the other hand, repeated COVID lockdowns and uncertainty about business conditions in China have added another layer of unpredictability to an already volatile market. Nevertheless, even as such uncertainty persists, Chinese officials and their Gulf counterparts continue to have their eyes trained on the longer term, as illustrated by the signing in August of a memorandum of understanding (MoU) between Saudi Aramco and the China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation (Sinopec) to team up on a wide range of joint venture projects in both countries, building on their collaboration.[40]

Similarly, even as China has taken steps to tighten the Belt and Road Initiative, BRI activities in the Middle East have not come to a dead end. Far from it. In January, China and Morocco signed an MoU facilitating joint implementation of the BRI[41] and Syria was welcomed as a new Belt and Road partner.[42] More recently, Chinese officials have vowed to forge ahead in seeking to harmonize the BRI and Egypt’s 2030 Vision.[43] In H1 2022, Middle Eastern countries received the largest share (33%) of Chinese BRI engagement (i.e., investment plus construction), and 57% of investments.[44]

Most of China’s BRI engagement in the region is focused on the energy sector. Saudi Arabia was the single largest recipient in H1 2022, with about US$5.5 billion[45] while Iraq had the third-highest construction volume (about $1.5 billion).[46] Despite China’s economic slump this year, Chinese state-owned companies have continued to pursue business in Iraq, where in 2021 they invested an estimated $10.5 billion in BRI-related and energy projects.[47] This past June, Iraq drew up a list of projects it intends to award to Chinese companies under a landmark oil-for-projects agreement signed with Beijing three years ago.[48] Finally, in pressing forward with efforts to reshape the BRI, China has found receptive partners, especially in the Gulf, for building out the Digital Silk Road (DSR).[49]

Conclusion

Having secured a third term as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and succeeded in packing the party’s top leaders with his allies and loyalists, Xi Jinping is poised to rule China essentially unchallenged. As Xi begins his new term at the helm, China’s economy is beset by problems. Yet, in his work report to the 20th Party Congress,[50] Xi struck a confident tone, insisting the economy is resilient and highlighting China’s growing strength and rising influence during his stewardship. Although Xi made clear in his speech that development remains the “top priority” and stressed continued focus on “high-quality growth,” he offered few hints of changing his approach after consolidating his hold on power.

The party’s November Politburo meeting and the Central Economic Work Conference in December could deliver important signals on Beijing’s economic policies going forward. However, specific policies and programs flowing from Xi Jinping’s report likely will not appear until the National People’s Congress meets next March. In the meantime, though, China’s economic outlook is darkening. Some predict that China will struggle to maintain growth of over 3% annually by the middle of this decade unless the government makes policy adjustments to overcome a shrinking population and weak productivity.[51]

Over the past decade, Xi’s vision, ambition, and personal authority have supplied the thrust and the policy direction that have enabled China-Middle East relations to flourish. Looking ahead, Xi will have an even freer hand than in his first two terms to impose his domestic and foreign policy choices. On the one hand, this provides some assurance that China will remain committed to deepening its engagement with MENA countries. On the other, it reveals the risks that MENA countries face if Xi’s policies were to prolong China’s economic slowdown and thereby increase the prospect of a global recession.

[1] Kevin Yao, “China’s economy brakes sharply in Q2, global risks darken outlook,” Reuters, July 15, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-q2-gdp-growth-slows-sharply-04-yy-missing-fcast-2022-07-15/.

[2] Takeshi Kiyara and Frances Cheung, “Economists cut China’s GDP growth outlook to 3.2%: Nikkei survey,” Nikkei Asia, October 7, 2022, https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Economists-cut-China-s-2022-GDP-outlook-to-3.2-Nikkei-survey.

[3] Michael Pettis, “How China Trapped Itself,” Foreign Affairs, October 5, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/how-china-trapped-itself; Edward White, “Xi Jinping’s last chance to revive the Chinese economy,” Financial Times, October 5, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/92cbe94d-05a0-4ece-bca9-68cb82244b17; and Ellen Zhang and Ryan Woo, “Analysis: A $1 trillion dollar headache: China’s local fiscal shortfall poses broader growth risks,” Reuters, October 16, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/1-trillion-headache-chinas-local-fiscal-shortfall-poses-broader-growth-risks-2022-10-17/.

[4] World Bank, “Reforms for Recovery,” East Asia and the Pacific Economic Outlook (October 2022): 60, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/38053/FullReport.pdf.

[5] Stella Yifan Xie and Jason Douglas, “China’s Economy Grew 3.9% in the Third Quarter,” Wall Street Journal, October 24, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-economy-grew-3-9-in-the-third-quarter-11666576957?mod=article_inline.

[6] World Bank, “Between Shocks and Stimulus,” China Economic Update, June 2022, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099640106102210762/pdf/P17579708f26d5018098840f1ad978bb54b.pdf.

[7] “China Must Stick With Zero Covid Policy, People’s Daily Says,” Bloomberg, October 10, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-10-11/china-party-paper-praises-covid-zero-again-dashing-easing-hopes?leadSource=uverify%20wall.

[8] “‘Dynamic zeroing’ is sustainable and must persist,” People’s Daily, October 11, 2022, https://wap.peopleapp.com/article/6889836/6753326.

[9] Kenneth Rogoff, “China’s Housing Crisis,” Project Syndicate, September 29, 2022, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-evergrande-real-estate-economic-rebalancing-by-kenneth-rogoff-2021-09?barrier=accesspaylog.

[10] Lili Pike and Alex Leeds Mathews, “China’s mortgage boycotts: Why hundreds of thousands of people are saying they won’t pay,” Grid, August 29, 2022, https://www.grid.news/story/global/2022/08/29/chinas-mortgage-boycotts-why-hundreds-of-thousands-of-people-are-saying-they-wont-pay/; Michael Pettis, “China’s Overextended Real Estate Sector Is a Systemic Problem,” China Financial Markets, August 24, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/chinafinancialmarkets/87751; and James Kynge, Sun Yu, and Thomas Hale, “China’s property crash: aa slow-motion financial crisis,” Financial Times, October 4, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/e9e8c879-5536-4fbc-8ec2-f2a274b823b4.

[11] Coco Liu, Zheping Huang, and Sarah Zheng, China’s Tech Giants Lost Their Swagger and May Never Get It Back,” Bloomberg, June 23, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-06-23/china-tech-crackdown-eases-but-startups-worry-xi-may-up-regulatory-pressure?leadSource=uverify%20wall.

[12] Josh Horwitz, “China steps up tech scrutiny with rules over unfair competition, critical data,” Reuters, August 17, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/china-issues-draft-rules-banning-unfair-competition-internet-sector-2021-08-17/; and “Factbox: How China's regulatory crackdown has reshaped its tech, property sectors,” Reuters, April 29, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/education-bitcoin-chinas-season-regulatory-crackdown-2021-07-27/.

[13] Chang Che and Jeremy Goldkorn, “China’ ‘Big Tech’ Crackdown; A Guide,” tThe China Project, August 21, 2021, https://thechinaproject.com/2021/08/02/chinas-big-tech-crackdown-a-guide/; “Factbox: How China's regulatory crackdown has reshaped its tech, property sectors,” Reuters, April 29, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/education-bitcoin-chinas-season-regulatory-crackdown-2021-07-27/; and Yi Wu, “China Eases its Crackdown on the Technology Sector: Recent Developments,” China Briefing, May 23, 2022, https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-tech-crackdown-recent-developments-signal-easing-regulations/.

[14] Eva Dou and Pei Lin Wu, “Once China’s darling, tech industry is burdened by covid and crackdowns,” Washington Post, May 16, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/05/16/china-tech-challenges-covid-crackdown/; and “Xi’s Tech Crackdown Fuels Another Crisis: Out-of-Work Youth,” Bloomberg, August 30, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-08-30/xi-s-tech-crackdown-fuels-another-crisis-out-of-work-youth?leadSource=uverify%20wall.

[15] “Alibaba, US-listed China stocks soar as crackdown fears ease,” Straits Times, June 7, 2022, https://www.straitstimes.com/business/companies-markets/alibaba-us-listed-china-stocks-soar-as-crackdown-fears-ease.

[16] Dennis Wong and Han Huang, “China’s Record Heat Wave, Worst Drought in Decades,” South China Morning Post, August 31, 2022, https://multimedia.scmp.com/infographics/news/china/article/3190803/china-drought/index.html.

[17] Laura He, “China’s worst heatwave in 60 years is forcing factories to close,” CNN Business, August 17, 2022, https://edition.cnn.com/2022/08/16/economy/sichuan-factories-power-crunch-china-heat-wave-intl-hnk/index.html; and Tiffany May and Joy Dong, “Factory Shutdowns, Showers for Pigs: China’s Heat Wave Strains Economy,” New York Times, August 18, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/world/asia/china-heat-drought.html; “Power Crunch in Sichuan Adds to Industry’s Woes,” Bloomberg, August 21, 2022; and Mark Schiefelbein, “China plans cloud seeding to protect grain crop from drought,” AP News, August 21, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/china-droughts-agriculture-climate-and-environment-647a2b13e8c14dc89b6a0161437d507a.

[18] World Bank, “China,” Climate Change Knowledge Portal, https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/china/vulnerability.

[19] Paul Krugman, “When Trade Becomes a Weapon,” New York Times, October 12, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/13/opinion/china-tech-trade-biden.html.

[20] Chad P. Brown, “US-China Trade Trade War Tariffs: An Up-to-Date Chart,” Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), April 22, 2022, https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/us-china-trade-war-tariffs-date-chart.

[21] “China’s chip industry set for deep pain,” Financial Times, October 8, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/e950f58c-0d8f-4121-b4f2-ece71d2cb267.

[22] Sam Wilkin, “How are leading companies managing today’s political risks?” WTW, March 31, 2022, https://www.wtwco.com/-/media/WTW/Insights/2022/03/2022-wtw-political-risk-survey-report.pdf?modified=20220803171235.

[23] Stella Yifan Xie, “Exports, the Engine of China’s Slowing Economy, are Sputtering,” Wall Street Journal, September 7, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/exports-the-engine-of-chinas-slowing-economy-are-sputtering-11662539157?mod=article_inline.

[24] A. Malik et al., “Banking on the Belt and Road: Insights from a new global dataset of 13,427 Chinese development projects,” AidData at William & Mary (2021), https://docs.aiddata.org/ad4/pdfs/Banking_on_the_Belt_and_Road__Insights_from_a_new_global_dataset_of_13427_Chinese_development_projects.pdf.

[25] In November 2020, with the effects of the pandemic adding more pressure on borrowers, Beijing agreed to sign up to the Common Framework, an international debt-relief effort endorsed by the G-20 that helps coordinate debt negotiations among creditors. Lingling Wei, “China Reins In Its Belt and Road Program, $1 Trillion Later,” Wall Street Journal, September 26, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-belt-road-debt-11663961638?mod=hp_lead_pos5.

[26] For analysis that refutes the China “debt trap” narrative, see: Lee Jones and Shahr Hameiri, “Debunking the Myth of ‘Debt-trap Diplomacy,’” Chatham House, August 2020, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-08-25-debunking-myth-debt-trap-diplomacy-jones-hameiri.pdf; Deborah Brautigam and Meg Rithmire, “The Chinese ‘Debt Trap’ is a Myth,” The Atlantic, February 6, 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2021/02/china-debt-trap-diplomacy/617953/.

[27] Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) and the Global Gateway initiative.

[28] Andreea Brînză, “What Happened to the Belt and Road Initiative?” The Diplomat, September 6, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/what-happened-to-the-belt-and-road-initiative/.

[29] Alicia García Herrero and Eyck Freymann, “A new kind of Belt and Road Initiative after the pandemic,” Bruegel Blog, June 23, 2022,

[30] Refinitiv, The great BRI reset, Infrastructure 360 Review – BRI Infrastructure 360 Review – BRI Focus (2022), https://www.refinitiv.com/content/dam/marketing/en_us/documents/reports/re1638498-cross-360-brochure.pdf.

[31] See, for example, remarks by Sun Yeli, the spokesperson for the 20th People’s Congress, who reaffirmed China’s commitment to the Belt and Road, stating: “We will strive for higher standards of cooperation, better deliverables from input, higher-quality supply, and stronger resilience in development.” Quoted in Xu Wei, “Commitment to Belt and Road reaffirmed,” China Daily, October 15, 2022, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202210/15/WS634aa7ffa310fd2b29e7cab4.html.

[32] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “Foreign Ministers of GCC Member States Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman and Bahrain and GCC Secretary General to Visit China,” January 8, 2022, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/wsrc_665395/202201/t20220108_10480226.html.

[33] Maziar Motamedi, “Iran says 25-year China agreement enter implementation stage,” Aljazeera, January 14, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/15/iran-says-25-year-china-agreement-enters-implementation-stage.

[34] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (MOFA), “Special Envoy of the Chinese Government on the Middle East Issue Zhai Jun Meets with Ambassador of Yemen to China Mohammed Al-Maitami,” October 19, 2022, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjbxw/202203/t20220319_10653467.html.

[35] “Germany’s Top Executives to Visit China,” Bloomberg, October 28, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-10-28/adidas-deutsche-bank-ceos-to-visit-china-with-german-chancellor-scholz-vw-boss. See also “Pakistan prime minister to visit China – Foreign Ministry,” Reuters, October 26, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/pakistan-prime-minister-visit-china-chinese-foreign-ministry-2022-10-26/; and Sebastian Strangio, “Vietnam’s Communist Party Chief to Visit China Next Week,” Diplomat, October 26, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/10/vietnams-communist-party-chief-to-visit-china-next-week/.

[36] “China’s President Xi to visit Saudi Arabia, says kingdom's foreign minister,” The National, October 27, 2022, https://www.thenationalnews.com/gulf-news/saudi-arabia/2022/10/27/chinas-president-xi-to-visit-saudi-arabia-says-kingdoms-foreign-minister/.

[37] Mordechai Chaziza, “Gulf states go digital with China,” East Asia Forum, October 7, 2022, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2022/10/07/gulf-states-go-digital-with-china/.

[38] Chen Aizhu, “China’s Sept crude oil imports fall, fuel exports hit 15-mth high,” Reuters, October 24, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/chinas-sept-crude-oil-imports-fall-fuel-exports-hit-15-mth-high-2022-10-24/.

[39] Chen Aizhu and Alex Lawler, “China buys more Iranian oil now than it did before sanctions,” Reuters, March 1, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-buys-more-iranian-oil-now-than-it-did-before-sanctions-data-shows-2022-03-01/; https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/russian-oil-supplies-china-up-22-year-close-second-saudi-data-2022-10-24/ ; Luke Pachymuthu, “Iran storing around 60 million barrels of oil on state-owned ships: Official,” Straits Times, October 12, 2022, https://www.straitstimes.com/business/companies-markets/iran-storing-around-60-million-barrels-of-oil-on-state-owned-ships-official.

[40] Saudi Aramco, “Aramco and Sinopec sign MoU to collaborate on projects in Saudi Arabia,” August 3, 2022, https://www.aramco.com/en/news-media/news/2022/aramco-and-sinopec-sign-mou-to-collaborate-on-projects-in-saudi-arabia#.

[41] Chris Devonshire-Ellis, “Morocco Upgrades China’s Belt and Road Initiative Financing & Investment Agreements,” Silk Road Briefing, January 10, 2022, https://www.silkroadbriefing.com/news/2022/01/10/morocco-upgrades-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-financing-investment-agreements/.

[42] “China Joins Belt and Road Initiative,” Al-Monitor, January 12, 2022, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/01/syria-joins-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative.

[43] Chris Devonshire-Ellis, “China Links Belt & Road Initiative Expenditure To Egypt’s 2030 Vision Development Plan,” Silk Road Briefing, June 20, 2022, https://www.silkroadbriefing.com/news/2022/06/20/china-links-belt-road-initiative-expenditure-to-egypts-2030-vision-development-plan/; and “BRI boosts Chinese investments in Egypt, says expert,” Xinhua, October 20, 2022, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202010/20/WS5f8e8097a31024ad0ba7fd56.html.

[44] Christoph Nedopil, “China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report H1 2022,” Green Finance & Development Center, FISF Fudan University Shanghai (July, 2022): 8, https://greenfdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GFDC-2022_China-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-BRI-Investment-Report-H1-2022.pdf

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] John Lee, “China to Study Iraq’s Offshore Oil Resources,” MENAFN, October 18, 2022, https://menafn.com/1105043262/China-To-Study-Iraqs-Offshore-Oil-Resources.

[48] “Iraq to Award More Projects to Chinese Firms,” Zawya, June 8, 2022, https://www.zawya.com/en/projects/construction/iraq-to-award-more-projects-to-chinese-firms-lic7coo2.

[49] See Nesrin Bakheit, “UAE open to China AI despite U.S. concerns: minister,” Nikkei Asia, October 15, 2022, https://asia.nikkei.com/Editor-s-Picks/Interview/UAE-open-to-China-AI-despite-U.S.-concerns-minister; John Calabrese, “China’s Digital Inroads into the Middle East,” East Asia Forum, October 19, 2022, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2022/10/19/chinas-digital-inroads-into-the-middle-east/; and Tala Michel Issa, “Huawei reaffirms dedication to aid Saudi Arabia’s shift toward carbon neutrality,” Al Arabiya, October 11, 2022, https://english.alarabiya.net/business/technology/2022/10/11/Huawei-reaffirms-dedication-to-aid-Saudi-Arabia-s-shift-towards-carbon-neutrality.

[50] “Transcript: President Xi Jinping’s report to China’s 2022 party congress,” Nikkei Asia, October 18, 2022, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/China-s-party-congress/Transcript-President-Xi-Jinping-s-report-to-China-s-2022-party-congress.

[51] China Pathfinder: ANNUAL SCORECARD Anticipating China’s Economic Future, October 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/ChinaPathfinder_Annual_2022.pdf.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.