This essay is part of the series “Turkey Faces Asia,” which explores the development of cultural, political, and economic links between Turkey and the Asia Pacific region. See more ...

Turkey’s “Middle Corridor” (MC) and China’s “Belt Road initiative” (BRI) are two grand schemes that envisage trans-continental integration. These two ambitious initiatives have been developed independently of one another. However, are they compatible?

Mapping the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Middle Corridor (MC)

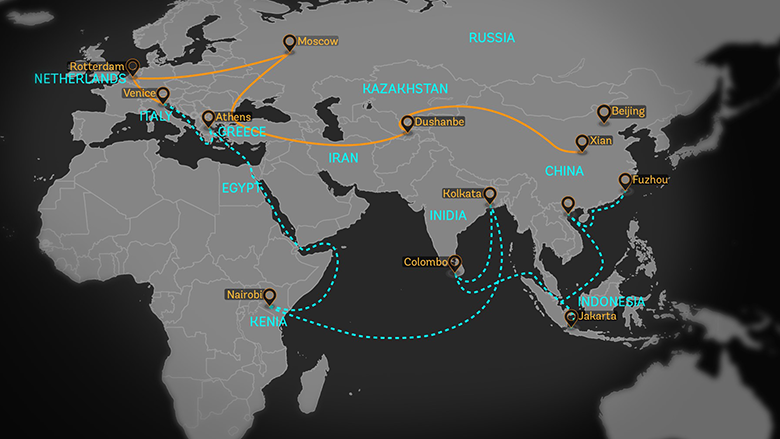

The BRI, which was first formulated by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013 during a trip to Central Asia, has resonated within and far beyond the region. This initiative, which has a broad geographic scope,[1] consists of two corridors: One route, known as the “Silk Road Economic Belt” (SREB), follows the historical overland Silk Road through Central Asia, Iran, Turkey and eventually to Europe. The other route, or “Maritime Silk Road” (MSR), originates in the South China Sea, passing through the Malacca Strait, the Indian Ocean, and the Red Sea and extending into the Mediterranean Sea.[2] [See Map 1.] Beijing has initially allocated about $152 billion of resources to the BRI from its Silk Road Fund, the China-led Asia Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB), the China Development Bank, the China Exim Bank, and the Agricultural Development Bank of China.[3]

Map 1. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

Source: The World Bank.

Recently, Turkey put forward a new Silk Road initiative named the “Middle Corridor.” Turkey’s main objectives in launching this initiative are to create a belt of prosperity in the region, encourage people to people contacts, reinforce the sense of regional ownership, connect Europe to Asia, notably the Caucasus, Central Asia, East Asia, and South Asia, create connectivity between the East-West corridor and the North-South corridor, expand markets and create large economic scales, and provide a concrete contribution to the development of regional cooperation in Eurasia.[4]

While representing Turkey’s own version of a Silk Road initiative, the MC is essentially based on the idea of establishing a region-wide railroad network. Its core aim is to extend the railway line that originates from Turkish territory to Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and others) via Transcaucasia (Georgia and Azerbaijan).[5]

The completion of the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway (BTK) and the subsequent modernization of all the railway systems in Turkey to allow for high-speed freight transit is a prerequisite for the realization of the entire project. [See Map 2.] The BTK, which became operational in October 2017, has the capacity to carry one million passengers and 6.5 million tons of freight per year in its initial stage of operation. Within several years, the BTK is expected to transport three million passengers and 17 million tons of goods per year.[6] Likewise, the SREB represents Beijing’s ambitions pertaining to the reinvigoration of the ancient Silk Road via an integrated railroad link between China and the Middle Eastern and European markets through Central Asia.

Map 2. The Baku–Tbilisi–Kars Railway

Source: Giorgi Balakhadze, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=52167737.

Compatibility of the Middle Corridor (MC) and the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB)

Looking at the various projects that have been fleshed out to date as part of the SREB and the MC, three routes appear to be the most promising in terms of facilitating the trans-continental integration of railway networks. The first route envisions connecting China to the Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR) through Russia via the Northern Corridor. However, this route would need to cover a huge distance to reach Turkey, hence rendering the MC rather unattractive and reducing its status to that of a peripheral, time-consuming alternative. Moreover, harsh winter conditions and political problems between Russia and Georgia would undermine the Northern Corridor’s feasibility for Turkey as an alternative route to reach China and East Asia.

A second alternative would be using the Southern Corridor to establish a link between the Turkish and Chinese Silk Road initiatives. This route would connect Trans-China Railway (TCR) to Kazakhstan. Under this scenario, the route would involve through Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Iran before reaching Turkey. China’s initial vision on the SREB tends to use the Southern Corridor for transportation and logistics links. If the SREB uses the Southern Corridor, it means the bypassing of the MC (See Figure 1.). However, the reinstatement of US sanctions on Iran in November 2018 under the Trump Administration has become an obstacle for China to use the Southern Corridor to realize its regional integration vision.

Besides, Ankara does not want to completely rely on Moscow or Tehran when it comes to strategic transport corridors that would serve as a gateway to the entire Asian continent. As a matter of fact, both Iran and Russia have played an inhibiting rather than facilitating role as far as Turkey’s opening to Central Asia in the post-Cold War period is concerned.

Yet a third alternative would be connecting the SREB with the MC through Central Asia and the Caspian Sea. The TCR can be integrated into Kazakhstan’s railway network and from there extend to Azerbaijan through a trans-Caspian roll-on/roll-off (RORO) link. The BTK railway would then connect this route to Turkey. A link between the SREB and the MC would be shorter and less costly than any alternative involving the Northern and Southern corridors.[7]

The agreement on creation of the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR) was signed in April 2016 in Baku by the railway authorities of Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Kazakhstan. TITR is a project initiated to improve transit potential and development of the countries of the Caspian region. This route runs from China through Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey and further to Europe. Furthermore, the Turkish railway authority (TCDD) joined to the TITR on February 16, 2018. China’s Lianyungang is an associate member of the TITR, along with the Ukrainian and Polish railways.[8]

With Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and now Turkey on board, China is aiming for China–Europe trade to reach 300,000 shipping containers annually via the Trans-Caspian Route by 2020. Fifteen thousand shipping containers per year is the agreed target for China–Turkey container traffic in 2018, with the cost of one container from Lianyungang to Istanbul by block train US$6,300. The TITR tariff rates for 2018 were approved at the meeting, considering the new Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway line.[9] At this juncture, there is a concern that Turkey will be bypassed by two ports on the Black Sea coast — Anaklia in Georgia and Constanta in Romania — from the SREB.[10]

The modernization of Turkey’s existing railroads includes plans by the State Railways of the Republic of Turkey (TCDD and the Ministry of Transport of the Peoples Republic of China (MoT China) to jointly construct a high-speed rail line between Edirne and Kars in Turkey. To date, however, Ankara and Beijing have been unable to reach a compromise on the project. Ankara has demanded full funding by China without offering the whole high-speed tender in Turkey to a Chinese-led consortium while Beijing has insisted that, if it covers construction costs, tenders be offered to Chinese companies.

In September 2018, Turkey reached a $40 billion deal with Germany to modernize the Turkish rail network. A consortium led by Siemens is to build new railway lines, electrify old ones and install modern signaling technology throughout the country.[11] This project is exactly the kind Beijing would like Chinese companies undertake.

Considering the Compatibility of the Middle Corridor and the Maritime Silk Road

Turkey has been developing links between the Silk Road and Turkish seaports and 16 international Ro-Ro lines in recent years in the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. There are also several ongoing major port investments in Turkey. The first, Mersin Port (on the Eastern Mediterranean coast), will have 11 million ton/year (TEU) capacity at an estimated cost of $3.8 billion. The second, Filyos Port (on the Western Black Sea coast), will have 700,000 TEU capacity at a cost of $870 million. The third, Candarli Port at Izmir (on the Aegean coast) will have 12 million TEU capacity, with the cost estimated at $1.24 billion. Turkey expects that Candarli Port would play a crucial role in the development of the Middle Corridor.[12]

So far, the initial projects developed under China’s MSR use the Greek port of Piraeus. The Greek government has provided many opportunities and privileges to Chinese companies investing in the country. In 2015, a consortium of COSCO, China Merchants Holdings International and China Investment Corporation spent US$920 million to buy a 65% stake at the Kumport terminal in Istanbul.[13] It seems that China Merchants Holdings has made this investment with the aim of using Kumport as a gateway to the Turkish market rather than as a regional hub. It is unlikely that Beijing considers Turkey part of the MSR, though Ankara has sought Turkey’s inclusion.

The BRI is also intended to serve the purpose of promoting the joint use of energy and natural resources as well as their extraction operations. The development of oil, natural gas, rubber, and metal resources, the operation of industrial plants, such as those processing cotton, and the construction of oil and natural gas pipelines will be key areas of investment and cooperation within the framework of the BRI. In that regard, as a starting point, there is increasing Chinese financial investments to realize some energy and mining projects in Turkey.

Since 2015, there has been increasing financial cooperation between Turkey and China, mostly in the form of Chinese infrastructure loans. The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), which acquired Turkish Tekstilbank in 2015, brokered an agreement between the Turkish and Chinese central banks to use Turkish lira and Chinese yuan instead of dollars and euros. The Turkish banking watchdog agency BDDK has granted operational rights in Turkey to the ICBC and the Bank of China in 2017. Turkish Akbank, Isbank, and Garanti Bank have branches in China.[14]

Furthermore, Turkey’s state lender Ziraat Bank signed a $600 million credit agreement with China Development Bank in December 2017. The AIIB extended a $600 million loan to Turkey in July 2018 to increase security of Turkish gas supplies. In July 2018, the ICBC also issued a $3.6 billion loan to increase the capacities of Silivri and Tuz Golu Natural Gas Storage Facilities, which will store 20 percent of Turkey’s natural gas on a yearly basis.[15]

Turkey has sought to hand over the tender of the third nuclear power plant (NPP) to a Chinese company after the Akkuyu NPP by the Russians and the Sinop NPP by the Japanese-French consortium. The Turkish government has initiated negotiations with the Chinese state-owned companies SPIC and SNPTC.[16] However, the Chinese side suffered a setback when, during negotiations in 2013, Sinop NPP was disqualified from the tender. The Mitsubishi-Areva consortium is set to abandon the Sinop NPP in December 2018, because construction costs have ballooned to around $44 billion.[17] Under these conditions, Beijing is not eager to start talks on a third nuclear power plant (possibly in Kirklareli) under the conditions that Ankara has offered.

Conclusion

Despite a very welcoming discourse of Ankara and Beijing on Silk Road cooperation, it is difficult to say that there is a road map to integrate the plans of the BRI and the MC. Ankara is demanding more Chinese investments in Turkish transportation, energy, and mining infrastructure and a flow of Chinese financial assets to Turkey without offering lucrative tenders to Beijing. Meanwhile, Beijing has not made clear its BRI vision to Turkey. Ankara’s NATO membership and economic integration with the European Union has made Beijing hesitant to declare its so-called grand strategy to Turkey. China’s bitter experiences with the Sinop nuclear power plant tender in 2013 and the air defense system in 2015 have also fed Beijing’s hesitation to become involved in strategic projects in Turkey. Moreover, it seems that trends in global politics such as the US-China trade war, the tumultuous US-Russia relations, the reinstatement of US sanctions against Iran, and the ongoing process to reach a final peace settlement in Syria have made the prospect of further Sino-Turkish cooperation in general even more unclear. In the absence of concrete offers by Ankara for projects for Silk Road cooperation, Beijing appears to prepared to pursue a wait-and-see policy to avoid the political uncertainties associated with any Turkey-related initiative.

[1] The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “Action plan on the Belt and Road Initiative,” March 30, 2015, http://english.gov.cn/beltAndRoad/.

[2] Chris Alden and Elizabeth Sidiropoulos, “Silk, Cinnamon and Cotton: Emerging Power Strategies for the Indian Ocean and the Implications for Africa” Policy Insights 18, (June 2015).

[3] Ariella Viehe, “U.S. and China Silk Road Visions: Collaboration, not Competition,” in Rudy deLeon and Jiemian Yang (eds.), Exploring Avenues for China-U.S. Cooperation on the Middle East (Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, 2015): 34-44.

[4] Selçuk Çolakoğlu, “Turkey’s Perspective on Enhancing Connectivity in Eurasia: Searching for Compatibility between Turkey’s Middle Corridor and Korea’s Eurasia Initiative,” in Jung-Taik Hyun (ed.), Studies in Comprehensive Regional Strategies Collected Papers. International Edition (Sejong: KIEP Publishing, 2016).

[5] Lintao Yu, “How the Belt and Road Initiative will help Turkey become the ultimate Eurasian playmaker,” Beijing Review, May 13, 2017.

[6] Leman Mammadova, “Development issues of Trans-Caspian int’l transport route discussed in Baku,” Azernews, January 18, 2019.

[7] A. Zafer Acar, Zbigniew Bentyn, and Batuhan Kocaoğlu, “Turkey as a Regional Logistic Hub in Promotion of Reviving Ancient Silk Route between Europe and Asia,” Journal of Management, Marketing and Logistics 2, 2 (2015): 94-109.

[8] Tristan Kenderdine, “Caucasus Trans-Caspian trade route to open China import markets“, East Asia Forum, February 23, 2018.

[9] Kamila Aliyeva, “Up to 4 million tonnes of cargo to be transported along TITR,” Azernews, February 19, 2018.

[10] Rıza Kadılar and Erkin Ergüney, “One Belt One Road: Perks and challenges for Turkey” Hürriyet Daily News, October 9, 2017.

[11] “Economic relations with Turkey vital for Germany, says envoy ahead of key delegation visit,” Hürriyet Daily News, October 23 2018.

[12] Altay Atlı, “Turkey seeking its place in the Maritime Silk Road,” Asia Times, February 26, 2017.

[13] Gavin van Marle, “China consortium moves into Turkish port market with control of terminal Kumport,” The Load Star, September 21, 2015.

[14] “Turkish regulator approves license for Bank of China to operate in Turkey,” Hürriyet Daily News, December 1, 2017.

[15] Matt Clinch, “China backs Turkey to overcome its economic crisis,” CNBC, Aug 17, 2018.

[16] “Turkey to build third nuclear power plant together with China,“ Trend News Agency, August 8, 2018.

[17] Takashi Tsuji, “Japan to scrap Turkey nuclear project,” Nikkei Asian Review, December 4, 2018.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.