This piece is part of the series “All About China”—a journey into the history and diverse culture of China through short articles that shed light on the lasting imprint of China’s past encounters with the Islamic world as well as an exploration of the increasingly vibrant and complex dynamics of contemporary Sino-Middle Eastern relations. Read more ...

Over the past two decades, China has assumed a more active role in shaping the outcome of conflicts in the Middle East where it lacked significant economic or material interests. More specifically, China has exhibited a degree of flexibility regarding its policy of non-interference in internal affairs, exemplified through a broader series of mediatory efforts in civil wars in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. China’s approach to conflict management has evolved, as have its motivations. This paper examines this evolution through the window of China’s conflict management in Sudan, Libya, and Syria.

China’s Evolving Approach to Mediation

Since the early 2000s, China has moved from being a conflict avoider to a conflict manager. China’s “Going Global” strategy of the late 1990s exposed Beijing to the hazards of pursuing interests in resource-rich, volatile regions in Africa and the Middle East. The incentives that attracted Chinese engagement in countries such as Sudan — raw materials, energy resources, oil, new export markets, etc. — were tethered to the stability of weak states, many of which were embroiled in or recovering from periods of civil war and instability.[1] China’s exposure to these risks grew as its economic engagement became more extensive, forcing Beijing deeper into conflict mediation, and at times even the active deployment of forces to protect its interests and people when mediation failed.

In response to iterative crises, Beijing has gradually assumed a more flexible and adaptive approach toward mediation to manage crises that pose a risk to its interests, and, if possible, resolve the conflict in a manner favorable to Chinese interests. This evolving diplomatic posture toward conflict is a sign that Beijing’s interpretation of “non-interference” in the affairs of another state is not fixed. Non-interference, one of Beijing’s central foreign policy tenants, is shaped by a significant degree of pragmatism,[2] especially when interests and assets are at stake.

In describing the modalities and rationale for the changing interpretation of non-interference, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi argues that China’s approach to conflict involves persuading peace (劝和), promoting talks (促谈), and mediation (斡旋调停), as opposed to imposing a solution or utilizing power politics to force an outcome.[3] In practice, this approach is highly flexible; China can determine its response to a crisis based on the specific context of the conflict and its impact on China’s national interests. This aims to provide China with more flexibility in creating a narrative to socialize its greater involvement in conflict mediation with regional actors,[4] while simultaneously distinguishing itself from western nations it perceives as interventionist. Chinese scholar Wang Yizhou terms this approach “creative involvement” — the use of cautious, selective, and constructive mediation.[5] In this way, Wang Yi notes, “more countries are willing to see and welcome China’s participation in the settlement of international and regional problems.”[6]

In practice, China’s approach to mediation blurs the line between involvement and intervention, and this ambiguity provides Beijing space for strategic posturing.[7] This curated diplomatic peace broker role, Mordechai Chaziza argues, is China’s “legitimate” means of intervening diplomatically to secure its own interests through conflict management in other states without betraying its non-interference principle.[8]

Sudan

China was initially indifferent to the state-led violence that erupted in Darfur, Sudan in February 2003. Believing the Darfur crisis to be a domestic issue, Beijing sought to avoid taking any adverse position that might threaten to undermine its petro-alliance with the Omar al-Bashir regime. The diplomatic cover that China appeared to provide the Sudanese government, however, provoked the ire of western nations, spurring calls for humanitarian intervention that, in turn, posed a potential threat to Beijing’s core interests in Sudan.

Under significant international pressure in 2004, China’s indifference gave way to “backseat” mediation. Beijing utilized its UN Security Council abstention across a series of key Darfur resolutions (including the March 2005 International Criminal Court referral of suspected Sudanese war criminals) and appointed a Special Envoy for African Affairs to engage more directly with Sudanese officials. These efforts aimed to exert quiet pressure on the Sudanese regime to improve the humanitarian situation in Darfur, cease the killing, and work to resolve the crisis.[9]

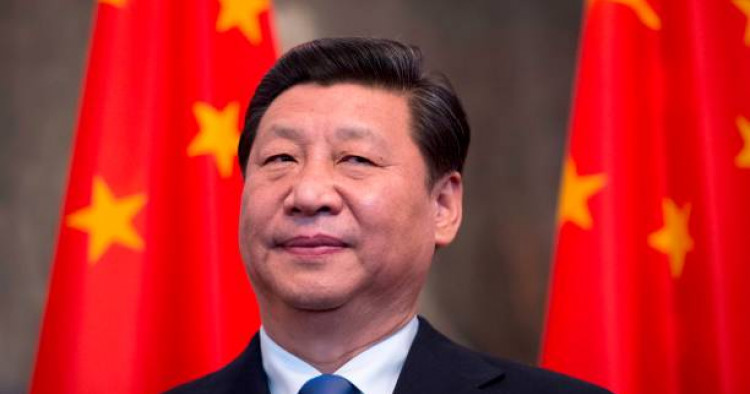

Chinese mediation efforts — including from President Hu Jintao and then-Vice President Xi Jinping — eventually persuaded Sudan to cooperate with the international community, and consent to a UN peacekeeping force in Darfur.[10] With Sudan’s consent, Chinese peacekeepers deployed alongside African Union (AU) troops and a very modest western military component. In doing so, Beijing preserved its resource interests, prevented the overthrow of the regime, and cemented a more consequential role in the security of East Africa through the deployment of its own PLA peacekeeping forces to Darfur.

China’s “backseat” mediation brought the Sudanese regime to the negotiation table. Miwa Hirono terms this as “medium-level interference,” in which the Chinese government interfered in the domestic affairs of the Sudanese state, but mostly with their consent.[11] China used its relationship with the Sudanese state, as well as its role as a principal mediator with the international community as a carrot to incentivize Sudan’s consent for a UN peacekeeping mission and a stick when Sudan diverged from China’s desire pathway, an approach Yun Sun points out China adapted to its peace mediation in Myanmar in 2015.[12] This approach, however, would not be reproducible in Libya.

Libya

In 2011, China abstained from the UN Security Council vote to authorize the military intervention (UNSCR 1973) that ultimately swept Muammar Gaddafi from power in Libya and drove the country into a full-blown civil war. The subsequent violence put over 35,000 Chinese citizens, 75 companies, and 50 large scale projects at risk.[13] In response, China carried out its largest ever overseas non-combatant evacuation operations (NEO) of more than 35,000 Chinese nationals in the span of 12 days — the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) largest overseas evacuation operation.

This experience became an important catalyst for China’s military modernization due to the gap in PLA capabilities which the experience exposed to China’s leadership. In the following decade, President Xi Jinping advanced the modernization of the PLA and expanded China’s military capabilities to secure its overseas interests through non-traditional security operations such as multilateral anti-piracy deployments in the Gulf of Aden and expanded participation in UN peacekeeping. Beijing gained additional experience and further expanded its capabilities to respond to potential threats to its overseas interests. On March 29, 2015, China’s PLA Navy (PLAN) evacuated nearly 600 Chinese citizens and 225 foreign nationals from Aden, Yemen to Djibouti. Two years later, China opened its first foreign military base in Djibouti, enhancing its ability to project power to protect growing interests in Africa and the Middle East.

The case of Libya also exemplified several key developments in China’s foreign policy learning curve. First, China’s abstention to UNSCR 1973 diverged from its normal political stance on non-interference. This change was largely driven by the consensus of Arab League and African Union member states who supported the resolution. China heavily weighed the opinions of regional organizations, and ultimately abstained in recognition of the interests of African and Arab interests. As a result, domestic critics accused China of “compromising its principles” and raised questions about whether the country had betrayed its non-interference principle.[14] China’s decision indirectly enabled the intervention, which exposed thousands of Chinese workers to the Libyan civil war and underscored China’s perceptions of the irresponsibility of western nations in resolving conflicts. This experience would ultimately shape China’s approach to the Syrian conflict, where it lacked significant material or economic interests, yet exerted significant international, multilateral, and bilateral diplomacy to shape the trajectory of the conflict.

Syria

In the early years of the Syrian civil war, China struggled to find its footing, and instead, sought to course correct from its previous engagement in Libya. While China lacked significant material or economic interests in Syria, the trauma of the Libyan intervention for China’s foreign policy establishment would place preventing regime change at the center of its Syria approach, with preventing a humanitarian crisis a secondary priority.

In the early years of the Syrian civil war, Chinese mediation was largely high-level, focused on using its P5 status to veto UNSC resolutions aimed at condemning or imposing sanctions on Assad for targeting civilians or which may be a western pretext for regime change.[15] China would remain dedicated to its anti-regime change stance, but would apply greater pressure on Assad through UN mechanisms to curb the regime’s violence against civilians following a series of deadly chemical attacks, government sieges, and aid blockades.

In February 2014, China voted in favor of UNSC Resolution 2139, which demanded the Syrian regime lift its sieges, facilitate humanitarian access, and deliver aid to the entire country. Assad defied the UNSC’s demands. In response, in July 2014, the UNSC unanimously approved Resolution 2165 and authorized UN cross-border aid delivery to Syria from neighboring states without the need for Syria’s consent or permission. The move — which signalled the loss of faith in the regime’s capability to provide for the protection of Syrian citizens — set a powerful precedent on the ability of the UNSC to intervene, without military force, in humanitarian crises.

China’s decision to support Resolution 2165 exemplifies its subtle interference in Syrian affairs, as reflected in several key factors: First, China’s efforts to improve the humanitarian situation in Syria were continually undermined by Assad’s use of force against civilians. Second, the regime’s defiance of UNSC demands for the cessation of violence only heightened international calls for military intervention and regime change. This put pressure on China to rein in Assad’s violence while simultaneously preventing his overthrow. Resolution 2165 enabled China to accomplish both. By agreeing to a cross-border mechanism, China traded Assad’s temporary loss of control over Syria’s borders, without regime consent, for the long-term security of the regime. The resolution relieved western pressure on China, and enabled Beijing to shift its focus from preventing regime change to building the regime’s capacity to eventually govern the entirety of Syria. And, because the resolution requires annual renewal, China has sought to gradually restore control of the borders to the Syrian government as conflict dynamics diminished.[16]

In more recent years, China has utilized its regional ties with Arab states to facilitate and encourage inter-Arab cooperation on Syria and facilitate the process of normalization. Whereas staunch adherence to this position has drawn significant criticism over the past decade, it eventually played to Beijing’s favor. Due in part to China’s role, the window for regime change has largely closed. The Arab League, and many Arab states, are increasing their engagement with Syria. In January 2022, Syria officially joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) after nearly five years of negotiations.

Conclusion

China is a new player in Middle East conflict mediation, relative to peer competitors — Russia and the United States. The principal distinction in its approach toward conflict is the extent to which Beijing emphasizes its core principle of non-interference, while simultaneously redefining acceptable “involvement” without crossing the red line of interference. From Sudan to Syria, China has slowly overcome its foreign policy learning curve, and learned to apply “creative involvement” to secure its desired outcomes.

This approach has enabled Beijing to utilize selective forms of “creative involvement” to advance its own objectives, and realign the behavior of states-in-conflict when they divert from the desired path, as observed in Syria and Sudan. China’s creative involvement is, however, an evolving concept. China’s struggles in Libya ultimately defined its more robust, comprehensive mediation in Syria. Meanwhile, even the worst consequences Beijing faced — the mass evacuation of citizens in Libya — became an important milestone in China’s learning curve and set the trajectory of its military modernization and long-term engagement in the Middle East.

As China gains more confidence in its mediation capabilities, MENA governments may find Beijing’s approach to be more assertive in pursuing its interests across a range of levers, including economic, military, diplomatic, and international engagement. With the United States trying to pivot to Asia, many nations in the region will be looking for others to fill the mediation vacuum the United States would leave behind.

[1] Shaio H. Zerba, “China’s Libya Evacuation Operation: a new diplomatic imperative—overseas citizen protection,” Journal of Contemporary China 23, 90 (2014): 1093-1112, DOI: 10.1080/10670564.2014.898900.

[2] Mordechai Chaziza, “China’s Approach to Mediation in the Middle East: Between Conflict Resolution and Conflict Management,” Middle East Institute, May 8, 2018. https://www.mei.edu/publications/chinas-approach-mediation-middle-east-between-conflict-resolution-and-conflict.

[3] “Wang Yi: Finding Ways to Solve Hot Spot Issues with Chinese Characteristics,” Xinhuanet, January 17, 2015. Translated from Mandarin, http://www.xinhuanet.com//world/2015-01/17/c_1114031581.htm.

[4] Fei Yu, “Third-Party International Conflict Management Research: China’s Post-Cold War Behavioral Patterns and Motivations (1989-2013), Fudan University, No.4, 2016.

[5] Wang Yizhou, “New Direction for China’s Diplomacy,” Beijing Review, March 8, 2012. http://www.bjreview.com.cn/world/txt/2012-03/05/content_439626.htm.

[6] “Wang Yi: Finding Ways to Solve Hot Spot Issues with Chinese Characteristics,” Xinhuanet, January 17, 2015. Translated from Mandarin, http://www.xinhuanet.com//world/2015-01/17/c_1114031581.htm.

[7] Degang Sun and Yahia Zoubir, “China’s Participation in Conflict Resolution in the Middle East and North Africa: A Case of Quasi-Mediation Diplomacy?” Journal of Contemporary China 27, 110 (2018): 224-243, DOI: 10.1080/10670564.2018.1389019.

[8] Mordechai Chaziza, “China Mediation Efforts in the Middle East and North Africa: Constructive Conflict Management,” Strategic Analysis 42, 1 (2018): 29-41.

[9] Gaafar Karrar Ahmed, “The Chinese Stance on the Darfur Conflict,” China in Africa Project, Occasional Paper No. 67, September 2010, https://media.africaportal.org/documents/SAIIA_Occasional_Paper_no_67.pdf.

[10] Ibid; Jonathan Holslag, “China’s Diplomatic Manoeuvring on the Question of Darfur,” Journal of Contemporary China 17, 54 (2007): 71-84. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10670560701693088.

[11] Miwa Hirono, “China’s Conflict Mediation and the Durability of the Principle of Non-Interference: The Case of Post-2014 Afghanistan,” The Chinese Quarterly 239 (2019): 614-634. DOI:10.1017/S0305741018001753.

[12] Yun Sun, “Syria: What China Has Learned from Its Libya Experience,” Asia Pacific Bulletin, 152, February 27, 2012, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/139823/apb152_1.pdf.

[13] Zerba, “China’s Libya Evacuation Operation: a new diplomatic imperative—overseas citizen protection.”

[14] Sun, “Syria: What China Has Learned from Its Libya Experience.”

[15] Paul Haenle, “China cannot rely on rhetoric alone to solve the Syrian issue,” Carnegie Tsinghua, June 9, 2014. https://carnegieendowment.org/2014/06/09/zh-pub-56114.

[16] See UNSC Resolutions 2165, 2449, and 2585.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.