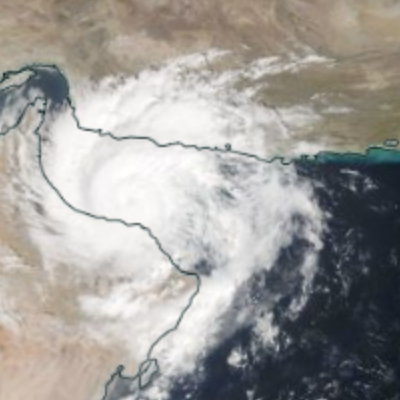

On Oct. 3 Cyclone Shaheen made landfall in Oman, near Muscat, after traveling through the Gulf of Oman from the Arabian Sea. According to the India Meteorological Department, which monitors and tracks the formation of cyclones in the North Indian Ocean, Cyclone Shaheen was categorized as a severe cyclonic storm when it made landfall with sustained winds of 70 miles per hour. Its arrival brought on heavy rainfall and excessive flooding in the many valleys that are a natural part of Oman’s topography. The high winds of the cyclone generated massive storm surges along the coast and caused serious damage to infrastructure and homes, displacing many. The death toll from these storm impacts in Oman alone is at least 14 people with the likelihood of that number increasing in the coming days. Surrounding countries have also felt the effects of this very severe cyclone, in the form of enhanced rainfall and winds in the United Arab Emirates and Iran, with the latter suffering structural damages, injuries, and fatalities.

Image from NASA Worldview

It is not uncommon for tropical cyclones to form in the north Indian Ocean on the southeastern Arabian Sea. The combination of warm sea surface temperatures in proximity to the equator (where most solar radiation is absorbed by the earth) and high relative humidity (atmospheric moisture) creates suitable conditions necessary to generate tropical cyclones west of India (with the Bay of Bengal providing similar cyclone-conducive conditions east of India).

Almost half of the tropical cyclones that are generated in the Arabian Sea do not make landfall, and most that do in the Arabian Peninsula become severely weakened, essentially downgraded in intensity to a depression. Some cyclones travel further west toward the Horn of Africa but tend to also lose intensity in that trajectory due to the relatively cooler waters of the western Arabian Sea.

Oman and Yemen have historically been the most impacted countries in the peninsula from cyclone activity due to the length of their combined coastline on the Arabian Sea. While very few cyclonic storms make landfall in these two countries at the higher level of cyclone intensity they may have possessed when formed in the Arabian Sea, these storms still bring with them the triumvirate of corresponding calamities: flooding, death, and destruction.

When severe tropical cyclones maintain their original intensity at landfall, truly catastrophic outcomes ensue. Cyclone Gonu struck the southeastern tip of Oman in June 2007 as an extremely severe cyclonic storm after having been categorized as a super cyclonic storm (the highest classification possible of a tropical cyclone) in the Arabian Sea. It remains the strongest and most devastating tropical cyclone to ever land on the Arabian Peninsula. With wind speeds in excess of 100 miles per hour, heavy rainfall, inland flooding, and strong coastal waves, Cyclone Gonu caused extensive damage and devastation to buildings and infrastructure along with widespread power outages. The final tally in cost of damages and fatalities for Oman was $4 billion and 50 lives, respectively. It still stands as the worst natural disaster in the history of Oman.

What’s different about Cyclone Shaheen?

Compared to significant tropical cyclones of the past that originate in the North Indian Ocean, the behavior of Cyclone Shaheen is somewhat unprecedented in the modern era and could represent a potential shift in how climate change is influencing the formation of extreme weather events that can afflict the Middle East. Two aspects of Cyclone Shaheen are particularly troubling if they become a common trait of future cyclones that may impact the Arabian Peninsula:

- Persistence of the cyclone over land: Cyclone Shaheen was formed in the Arabian Sea from the remnants of a previous cyclone: Gulab. Cyclone Gulab originated in the Bay of Bengal before traveling west across India, progressively downgrading in intensity to a depression. Instead of fully dissipating after losing much of its intensity, the remnants of Cyclone Gulab reenergized in the Arabian Sea and moved west into the Gulf of Oman. As it began to enter the Gulf of Oman, Cyclone Shaheen became a very severe cyclonic storm, making it a stronger cyclone with faster windspeeds than the original cyclone (Gulab) from which it sprang. Cyclone Gulab/Shaheen’s remarkable path from the Bay of Bengal across the width of India and over the Arabian Sea to Oman has only been evidenced twice in modern history: in 1921 and 1959. And in neither of those instances did the cyclone make landfall as a very severe cyclonic storm like Cyclone Shaheen.

- Movement of the cyclone beyond the Arabian Sea: Very few of the tropical cyclones that originate from the Arabian Sea travel into the Gulf of Oman, and even fewer make landfall in the Arabian Peninsula as a very severe cyclonic storm after traversing the Gulf of Oman. With the exception of Cyclone Gonu (where landfall occurred at the southeastern tip of Oman before the cyclone traveled the Gulf of Oman and dissipated in Iran), there are only two records of severe cyclones moving from the Arabian Sea into the Gulf of Oman and making landfall in northern Oman (near Muscat). The first was in June 1890. The second? Cyclone Shaheen, over 130 years later.

Traditionally, tropical cyclones forming in the Arabian Sea do not travel beyond the Gulf of Oman or deep inland across the Arabian Peninsula. The dry air and reduced moisture over the Arabian Peninsula in comparison to the Indian Ocean is an impediment to that type of cyclone trajectory, robbing a potentially severe cyclone of its intensity and accelerating its eventual dissipation. But the increased warming of the oceans and seas near the equator as evidenced by rising sea surface temperatures, coupled with climate projections of increased global warming in the future, signals the potential of more frequent and intense cyclones landing well into the Arabian Peninsula and surrounding regions. This makes Cyclone Shaheen both a reminder of the peninsula’s vulnerability to extreme weather events and an early indicator of how climate change is exacerbating that vulnerability.

Mohammed Mahmoud is the director of the Climate and Water Program and a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute. The opinions expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by HAITHAM AL-SHUKAIRI/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.