The viability of Eastern Mediterranean natural gas resources has long been a source of debate for reasons including cost considerations, market demand, and regional geopolitical tensions. The past couple of years have further complicated the debate, introducing new questions about the role of these resources in supporting post-pandemic economic recovery or helping more advanced markets achieve net-zero policies by replacing coal and other fuel sources (a particularly relevant topic of debate given Europe and Asia are key export targets for East Med gas).

The answer remains elusive. Regional players like Egypt, Israel, and Cyprus appear as determined as ever to get their gas to market, certainly motivated in part by concerns about stranded assets in a period when decarbonization pressures are rapidly escalating. At the same time, international oil companies remain heavily engaged in regional project development despite increasing investment restrictions tied to new corporate climate policies. Although the economic and political costs associated with some of these projects are higher, these companies are no doubt drawn to the geographic allure of the region, situated at the nexus of Europe, Asia, and Africa, which presents a lot of export optionality.

East Med suppliers must walk a fine line between trying to capitalize near term on their abundant resources while investing in improved regional interconnectivity and technology that will help them create a sustainable energy market in a decarbonizing world. The importance of the latter cannot be overstated — without a more strategic and integrated regional strategy, the current fluctuations in global gas markets pose too much investment risk to massive-scale gas projects in the region with 20-30-year time horizons.

Current global competitiveness of East Med gas

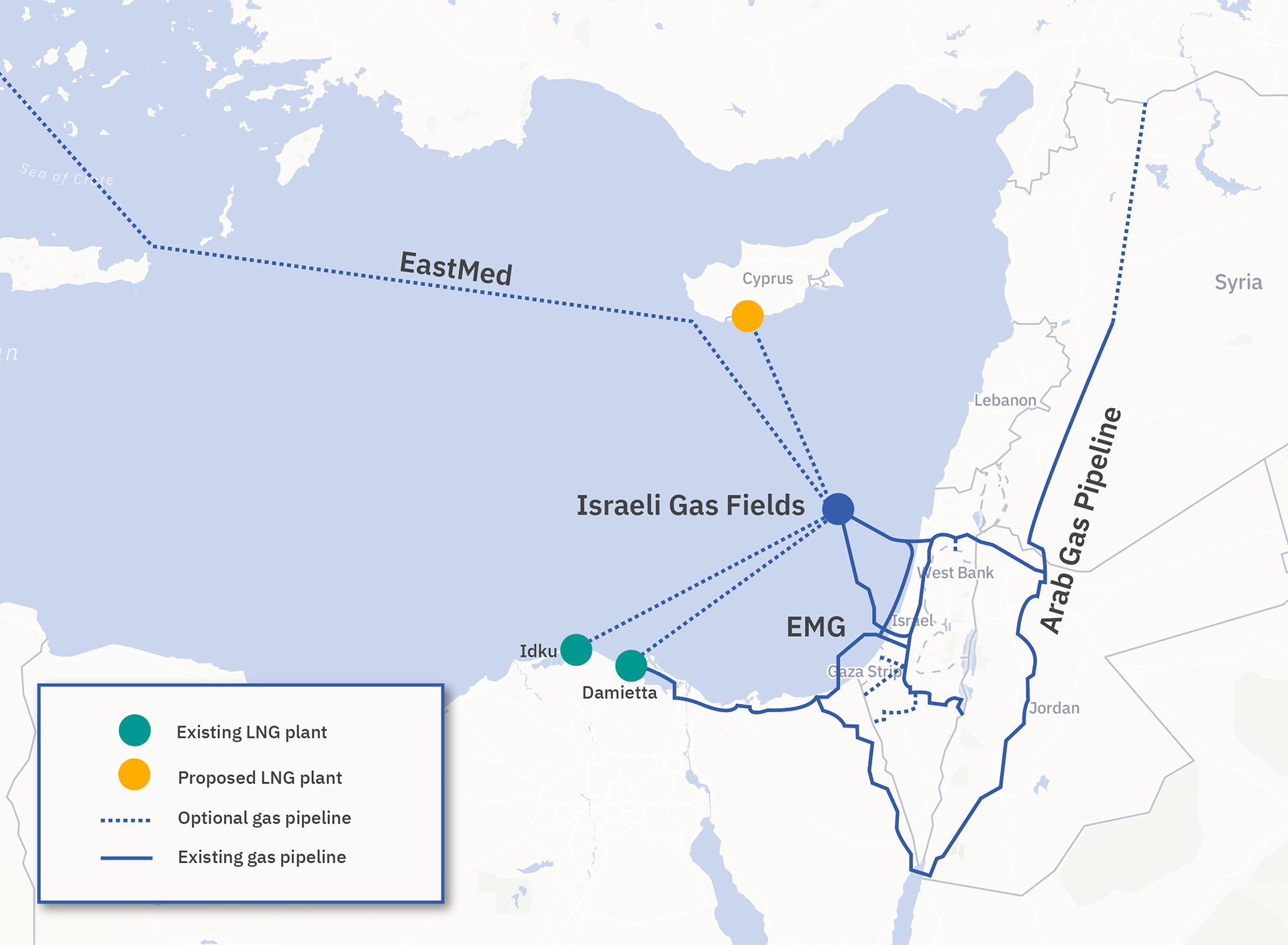

At present, Egypt is the primary outlet for regional gas to reach global markets in the form of liquefied natural gas (LNG). According to Platts Analytics data, Egypt exported a total of 2.77 billion cu meters (bcm) and 2.42 bcm respectively in the first two quarters of the year from its two LNG terminals, the 7.2-million-tons-per-annum (mtpa) Idku facility and the 5-mtpa Damietta plant. This obviously points to considerable extra capacity, which regional players are angling to fill, but importantly, Egyptian LNG is also exposed to spot prices, which complicates export prospects. This was particularly evident over the past year when commodity prices saw dramatic fluctuations as markets experienced uneven, post-COVID economic recovery.

Earlier this year, when spot LNG prices were in the $5-7 per metric million British thermal unit (mmbtu) range, this was uncomfortably close to breakeven prices for Egyptian LNG of around $5/mmbtu and the existing Egypt-Israel gas export agreement priced at $6/mmbtu, leaving little room for profit. Then, as spot LNG prices hit record highs more recently — spot Asian LNG prices, for example, were trading at around $20/mmbtu — Egyptian LNG exports could have earned sizable margins, but buyers were changing their behavior. Major spot gas buyers like China and India recently turned to more domestic gas, prices for which are typically oil-linked, to secure more affordable options, and still other buyers have sought options to expand deliveries within term contracts. In Europe, there are renewed concerns of potential gas shortages moving into the winter as providers have been unable to fill critical storage with prices so high. While these current pricing conditions should have been far more beneficial for East Med exports, there were no significant new buyer-supplier channels to emerge as buyers adapted their own behavior. As global markets stutter toward recovery post-pandemic with the added dimension of growing decarbonization demands on energy markets, East Med suppliers will have to think outside the box when it comes to marketing their gas supplies.

Beyond price-specific considerations, regional producers will have to weigh their competitiveness against major national oil companies operating in their key export markets like Gazprom or Qatar LNG, which benefit from low-cost resources, greater price flexibility, and the ability to finance major projects like export terminals and long-distance pipelines. In this context, Asian export markets look less realistic for the East Med given added shipment time and costs, and the abundance of LNG supplies situated in closer proximity at lower costs. East Med suppliers will likely have to focus instead on more localized options and European buyers, which will require strategic thinking about changes in European climate policies.

Europe the best export bet, but East Med exporters must adapt and prepare to compete

The EU presents an interesting case for East Med suppliers. Russia’s deeply entrenched pipeline connections to the market, further reinforced by the latest Nord Stream 2 developments, create challenging conditions for newer gas market entrants. Nevertheless, the EU remains heavily engaged in the East Med and will uphold the status of several major proposed regional projects, including the EastMed pipeline (connecting regional resources to Greece via Cyprus) and the Melita TransGas Pipeline (linking Malta and Italy), as “projects of common interest” (PCI) that can access EU funds through end-2027. The EU is also maintaining funding for Cyprus’ planned gas import terminal currently under construction.

However, East Med producers should be careful not to fall into complacency about EU support. The EU is set to publish the EU Taxonomy Regulation before the end of the year, which will follow up on the Green Deal and recently released Fit for 55 package to provide further guidance on the transitional role of gas. In 2025, it will review the carbon border adjustment mechanism, which seeks to impose a levy on imports from carbon-intensive sectors with lower environmental standards than the EU. This could result in more direct targeting of gas through a hefty carbon price in a matter of years.

East Med producers must look ahead and consider reducing carbon intensity to access the EU market, while also finding outlets for their own gas supplies domestically to support renewables development, hydrogen blending initiatives, and other energy transitions and regional integration projects that can support long-term prospects for the industry. To some extent, the East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF) was established in 2019 to help support these objectives. But the glaring omission of Turkey, and several other regional players, from EMGF will likely impinge on the forum’s success and require continued interventions, including from the U.S. and EU, to manage geopolitical tensions (originating not just from Turkey, but even from Chinese interests in regional power market infrastructure) and forge ahead with regional energy projects.

Investments in East Med gas: Regional integration and thinking outside the box

Sizable gas investments are still planned for the region in the years ahead, even as companies face tighter carbon restrictions and more uncertain market conditions. Companies are drawn by the huge, still untapped resources, while some of the smaller or lesser-developed economies of the region are anxious for additional revenue streams. Alongside these projects, there are also notable investments and feasibility studies being conducted to assess clean energy solutions and address growing climate concerns. The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report designated the East Med as particularly susceptible to climate change with average temperatures expected to far exceed the global 1.5 C target. Given this confluence of interests, the region will need to focus on an all-of-the-above solution to boost revenues and support economic growth over the near term with gas exports while pursuing options to support clean energy solutions and mitigate environmental damage for the future.

For now, gas remains at the core of any energy strategy for the region as billions of dollars continue to pour into major regional projects. Egypt’s gas-rich deepwater and the Nile Delta remain attractive investment destinations for the oil majors as the country seeks to continue building its gas hub status. Phased reductions in fuel subsidies have helped lend support to sales prices, and assuming reforms stay the course, this should improve attractiveness for investors.

However, Egypt’s existing 12.5-mtpa LNG export capacity, and the risk that domestic gas supplies could be insufficient to keep up with export capacity, has encouraged continued commitment to other regional gas projects, including offshore Cyprus, where partners at the Aphrodite field (Delek, Chevron, and Shell) are still reviewing a final investment decision on a pipeline to ship gas from the field to Egypt for liquefaction and export. ExxonMobil and Qatar Petroleum are to appraise their Glaucus discovery, and Total and Eni will do the same at Calypso (although regional disputes and the pandemic have slowed some of these plans). Similarly, in Israel, Chevron’s interests in the Leviathan and Tamar fields could become a critical feedstock source for Egypt’s LNG plants as the company considers investing $235 million in a subsea pipeline project that could double Israel’s gas export capacity to Egypt (to support these plans Israel is currently assessing whether to increase annual natural gas export quotas). Given previous disputes with Egypt over halting gas exports and arrears, partners at Leviathan are also considering a floating LNG unit to maintain more control over their own gas exports.

Perhaps the biggest outstanding investment in the region concerns the EU-backed $7 billion EastMed pipeline, intended to carry gas from Israel to Cyprus and Greece. The project has its share of skeptics that question both the price tag and the logic of a major gas transport project to Europe at a time when EU decarbonization pressures are growing so rapidly. With the amount of uncertainty about how EU climate policies and regional geopolitical tensions could impact some regional energy ambitions, there are other, lower-cost projects under consideration that could be prioritized to promote regional integration and use gas resources for advancing energy transitions and electricity access.

Regional pipelines already link key regional markets (i.e., Israel to Egypt, or Egypt or Israel to Jordan), but a new proposal, for example, looks at options to use Egyptian gas to supply Lebanon via Jordan and Syria to address acute power shortages in Lebanon. Two other mega-projects seek to link regional power grids. One, the EuroAsia Interconnector, would link Israel, Greece, and Cyprus via a 1200-km subsea high-voltage transmission cable to end electricity isolation in both Cyprus and Israel. The EU includes the project as a PCI due to its ability to help complete the European Internal Market, meaning the project would qualify for financing from the Connecting Europe Facility. A similar project is under consideration to connect the grids of Egypt and Europe via Cyprus and Greece, known as the EuroAfrica Interconnector. These projects have generated particularly strong interest because of their ability to leverage local gas supply to improve regional electrification and to help manage the intermittence of regional and European renewables projects.

Across the region, countries are also introducing more ambitious renewables targets, from Greece (targeting 65% of power generation from renewable energy sources by 2030) to Israel (30% from renewables by 2030) and Egypt (42% of its power from renewables by 2035, although a current proposal from the Ministry of Electricity and Renewable Energy seeks to push that up to 60%). Achieving these targets requires crucial investments into expanded clean energy and renewables capacity, including into hydrogen projects. The best bet for East Med producers is to pave the way for a sustainable, regional gas market that supports a combination of gas and renewables to move toward cleaner power generation models and improved electricity access and interconnectivity.

If the EU and global energy majors can help facilitate the transition process by continuing to ramp up investments into renewables and clean tech projects, the region would further gain from moving along the energy transition curve and remaining competitive even amid uncertainty and increasing carbon restrictions in global markets.

Emily Stromquist has over a decade of experience advising corporate and financial services clients on global energy market trends and political risk, and has lived and worked across Europe, Eurasia, the Middle East, and Africa. She is currently a Managing Director at Teneo, the global CEO advisory firm, and a Non-resident Scholar with MEI’s Economics and Energy Program. The opinions expressed in this piece are her own.

Photo by Athanasios Gioumpasis/Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.