Originally posted June 2011

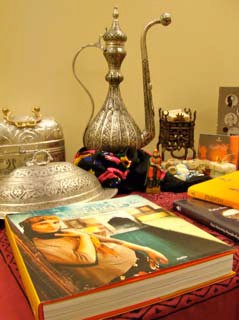

The waiting area of the Istanbul Center is welcoming. Two camel-colored leather sofas face two camel colored leather loveseats. The artifacts on the end tables and in the display cases appear to be carefully placed. A Turkish flag sits next to an American flag on a small table. The only non-permanent items in the room are two posters taped to the glass, one advertising the art contest, the other advertising the essay contest. The Center appears to be a place of great activity — many faces pass by, multiple conversations occur. Despite the activity, the individuals at the center appear calm, some may say serene, not overwhelmed by what seems to be a very full plate.

While waiting, a young woman entered the room quietly carrying Turkish coffee on a beautiful silver tray. “Have you had it before?” I answer, “No.” She smiles and quietly says, “I’ll bring some water.” She returns with waters and candies, again quietly leaving but pausing to ask, “Would you like the door open or closed?” This hospitality reflected the very mission of the Istanbul Center — Education through dialogue, through presence. Outside of active involvement in the many projects they support, the staff and volunteers of the Istanbul Center share their mission even in a brief period of waiting for a meeting to begin.

Dr. Sandra Bird approached me in the fall, 2009, and asked if I would offer evaluative feedback concerning the Annual Istanbul Center Art Contest. he Annual Istanbul Center Art and Essay Contest is the largest part of the Istanbul Center’s Education Component, and, is an estimated 30% of the overall work of the Istanbul Center. Over the four years of the contest’s existence, the rate of participation has been explosive. And, with the vision of both Gurkan Ekicikol, the Director of Education Programs, and Tarik Celik, the Istanbul Center Executive Director, the contest will continue its explosive growth to include reaching students outside of Georgia, including the greater Southeastern United States, with the understanding that eventually it will reach the national level, and then the international level. The purpose of these remarks is to give some indication of the quality of the program, as well as issues that should be addressed with a formal evaluation process. These remarks are, of course, limited, as the data gathering and analysis has been largely casual and constrained in nature. Despite the limitations, these remarks are specific to the Istanbul Center Contest, without a goal of generalizing. These remarks are intended for the staff of the Istanbul Center, the advisory board, and stakeholders.

Dr. Sandra Bird approached me in the fall, 2009, and asked if I would offer evaluative feedback concerning the Annual Istanbul Center Art Contest. he Annual Istanbul Center Art and Essay Contest is the largest part of the Istanbul Center’s Education Component, and, is an estimated 30% of the overall work of the Istanbul Center. Over the four years of the contest’s existence, the rate of participation has been explosive. And, with the vision of both Gurkan Ekicikol, the Director of Education Programs, and Tarik Celik, the Istanbul Center Executive Director, the contest will continue its explosive growth to include reaching students outside of Georgia, including the greater Southeastern United States, with the understanding that eventually it will reach the national level, and then the international level. The purpose of these remarks is to give some indication of the quality of the program, as well as issues that should be addressed with a formal evaluation process. These remarks are, of course, limited, as the data gathering and analysis has been largely casual and constrained in nature. Despite the limitations, these remarks are specific to the Istanbul Center Contest, without a goal of generalizing. These remarks are intended for the staff of the Istanbul Center, the advisory board, and stakeholders.

The organizing question for these remarks is: Based on limited involvement are there suggestions for improving the contest or contest process? These remarks stem from data gathered using the following methods: interviews with Dr. Sandra Bird, university coordinator for the contest; interview with Katherine Whitehead, PR Coordinator and Ekicikol, Director of Educational Programs; group interview with Dr. Sandra Bird, Whitehead, Ekicikol, and Executive Director Celik; observation of judging component of the contest; brief observation of the center, itself; informal interviews with judges; and, brief data review of Istanbul Center Program Information.

Those involved in this contest, including the staff of the Istanbul Center, as well as judges, are passionate about the mission and eager for the growth and impact. There is some concern about how to attain broader understanding of the impact of the investments. Anecdotal remarks indicate that those involved desire to gain understanding of both quality of the contest, and ability to evaluate the contest for future high quality growth.

At this point, the rapid rate of growing involvement is an indicator of success. Judges stated that the quality of work is rising yearly. Istanbul Center staff indicated that more teachers are choosing to encourage student participation. Additionally, the contest has been replicated by other agencies. These pieces of evidence are vital. Along with having this information, further analysis of the information could help the center continue in lines of quality to implement the great ambitions for the contest. Staff indicated designing a survey to gain data concerning the contest, distributing it to teachers, students, and parents would be beneficial/desired.

At this point, the rapid rate of growing involvement is an indicator of success. Judges stated that the quality of work is rising yearly. Istanbul Center staff indicated that more teachers are choosing to encourage student participation. Additionally, the contest has been replicated by other agencies. These pieces of evidence are vital. Along with having this information, further analysis of the information could help the center continue in lines of quality to implement the great ambitions for the contest. Staff indicated designing a survey to gain data concerning the contest, distributing it to teachers, students, and parents would be beneficial/desired.

The Judging

I arrive at the Istanbul Center on a grey Friday morning. It’s cold, and the forecast is snow. I easily navigate parking, and a friendly stranger in the lobby points me in the direction of the right elevator. I find the Istanbul Center suite, and the locked door is quickly opened. Sandra Bird appears in the entry and directs me to a back room where Michelle Marlar from Morehouse College sits, looking at student work. The table is covered by student work.. The other judges arrive shortly, and Dr. Bird offers remarks about the judging process. “My students have gone through and made initial assessments using the rubric attached to the piece. They placed the higher ranked works in Pod 1, and the rest in other piles.”

The judges were told that they had complete freedom to make their own decisions based on aesthetics, which could include moving pieces from “excellent,”“middle,” and “poor” categories. Dr. Bird indicated interest in possible discrepancy between students and judges. Throughout the process, there were pieces pulled from “poor” and “middle” and moved to “excellent.” And, at times, pieces in the “excellent” category were moved down. The presence of the rubric component concerned some judges. “Are we supposed to fill one out, too?” was a question asked by a puzzled judge. “I have never been a part of an art competition where I was asked to follow a rubric…” Some pieces were missing rubrics that had fallen off during transport; confusion occurred when pieces were ranked the same number, but placed in different categories. Melody asked why there was this discrepancy. It was evident that students assessing the work struggled with the task of assigning a number and category of rank.

Don asked if the focus should be more on use of elements or aesthetics, “to determine level of judgment.” Early in the process, judges learned that while certain pieces were disqualified for not meeting size requirements, those missing an artist statement were included because the Istanbul Center decided “not to throw out an excellent piece.” Carole was puzzled by the decision to allow pieces that had not followed requirements, while dismissing others. Sandra indicated that disqualification was largely based on studio criteria, not overall criteria.

The concern with the rubric continued to be a part of the conversation throughout the morning. Carole mentioned that an entry had not dramatically altered appropriated images, and moved it to the “poor” category. Don pulled a piece from the poor category commenting,“I don’t know if is the best work, but it is interesting…” Additional conversation brought the question, “Do you pay more attention to craftsmanship or concept?” There were strong pieces that did not focus obviously enough on the theme of the contest. Judges agreed they were looking for more than “good student work.”

A fter a short time judges were treated to a Turkish lunch. Gurkan had collected the donated dishes from various homes that morning. Judges sat and ate with several members of the Turkish center, conversations ranged from talk of the center, education, art, and others. The lunch lingered, and judges slowly returned to the task. While initially judges were gathered in around a small table stacked with pieces, when lunch was cleared stacks were carried out into a larger space to be spread out for judging.

fter a short time judges were treated to a Turkish lunch. Gurkan had collected the donated dishes from various homes that morning. Judges sat and ate with several members of the Turkish center, conversations ranged from talk of the center, education, art, and others. The lunch lingered, and judges slowly returned to the task. While initially judges were gathered in around a small table stacked with pieces, when lunch was cleared stacks were carried out into a larger space to be spread out for judging.

As judges spread the work on tables, I had the opportunity to briefly interview Cassandra and Gurkan concerning the art contest. I explained my role, to offer evaluative feedback, and asked that they help me understand the broader goals of the contest. Gurkan quickly began, “Our mission is to contribute to the educational system; to help youth understand global concepts and values. The human nature theme (reaching a global theme) helps the Istanbul Center to build relationships affecting youth. We want to help students learn how to think bigger so they can change the world.” Entries grew beyond 2,000 this year, and included 135 public schools and 5 private schools from 51 counties. Gurkan and Cassandra both indicated that they wanted to examine the impact of this growth.

The final judging process occurred with little discrepancy among judges. The top ten pieces were ranked after conversation and adequate assessment time. Snow began to fall outside the Istanbul Center, and the judges, having successfully completed their task, made their way to their cars.

Weeks after the judging of the competition, the Istanbul Center hosted an awards ceremony for the winning students, their teachers, their superintendents, the judges, and other friends and supporters of the center. Described as a “lavish” event, it was reported an overall success. Two individuals indicated concern that there may need to be more balance in celebrating the achievements of winners and promoting the mission of the Istanbul Center.

With the many successes of the art contest in terms of mission of the Istanbul Center, it is easy to understand the larger scope that members of the Center have for the contest. But, as the contest grows, a formal evaluative component of the benefits and operations of the contest should occur. Through my limited study of the judging component of the contest, I am left with two questions that should be considered in the development of an evaluation component. The first, specific to judging, is “Who should design the judging component of the contest?” The second is “How can the Istanbul Center gather and analyze data that would promote quality growth in all aspects of the contest?” It was mentioned that parents, students, and teachers would be surveyed as a step in this direction. However, even in the survey design, great care should be placed on understanding the strategies involved in gathering quality feedback for reflection and growth.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.