The Soberana-2 COVID-19 vaccine is among Cuba’s most recent efforts at bilateral cooperation with Iran. Commonly referred to as Pasteurcovac in Iran, the jab was developed as part of a collaboration between the Finlay Institute of Vaccines in Havana and the Pasteur Institute of Iran, and is reported to be 91.2% effective. In June, the Soberana-2 vaccine received emergency-use approval in Iran. About a month later, Cuban state-owned media announced that Iran would be the first country outside of Cuba to produce it at an industrial scale. In September, Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian spoke of the “unlimited” potential to expand Tehran-Havana ties, and both sides have highlighted the fields of medicine and agriculture as ideal areas for cooperation. While that might be the case, there is no denying that the Iran-Cuba partnership represents the coming together of two entirely different political models that above all rests on shared conflict with the United States.

The origin of ties

Relations between Cuba and Iran began following the 1979 Iranian Revolution, when the latter adopted a theocratic-republican constitution and an anti-imperialist ideology focused on opposition to Western powers. Joining the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) quickly thereafter, the nascent Islamic Republic sought independence from the U.S. and Soviet spheres of influence. Meanwhile, the late Cuban President Fidel Castro secured the seat of chair as de facto spokesman at the NAM conference that same year, cementing Cuba’s leadership in the organization.

The NAM’s role in forging Cuba-Iran ties should come as no surprise. At the time, it had a total of 90 member states that shared similar anti-imperialist views, and participation in the bloc was perceived by Iran’s then-Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini as the obvious path toward neutrality in the midst of the Cold War while also providing Iran with diplomatic and economic partners among fellow NAM members. Still, while shared anti-U.S. sentiment is often cited as the foundation for the 42-year-long partnership between Havana and Tehran, is a common antagonist enough to sustain almost half a century of close ties?

The Cuban perspective

For the post-1959 Cuban communist system, having a powerful ally that stands behind it in the face of the U.S. has tended to trump other factors. This has been the case for Iran as well, as both nations have a long history of tensions with the U.S. Throughout the years, Cuba has faced not only U.S. sanctions and punitive measures by the international community, but also being labeled as a state sponsor of terrorism, a campaign spearheaded by Washington.

Much like Iran’s leaders, Fidel and Raul Castro and Cuba’s current president, Miguel Díaz-Canel, have kept their domestic human rights laws vague, engendering criticism by international human rights organizations. Two years ago, the widely underreported San Isidro Movement, led by artists, journalists, and academics, demonstrated against state censorship of artistic activity, only to be met by police brutality and disappearances. On July 11 this year the biggest protests in decades broke out following food and medicine shortages on the island.

Partners like Iran have a history of showing support to Havana, given the latter’s aggressive anti-U.S. foreign policy and favorable geostrategic location. Iran has compensated Cuba directly for allowing it to “clandestinely engage in electronic attacks” from the island, starting with Iranian President Mohammad Khatami’s 20 million euro annual credit line between 1997 and 2005, and later expanded to 200 million euros by his successor Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Iran has never failed to support Cuba on the international front in return for its intelligence services. When asked about Cuba’s violent crackdown on the recent protests, Iranian Foreign Ministry Spokesman Saeed Khatibzadeh predictably denounced U.S. support of the San Isidro Movement, accusing Washington of “seeking to interfere with the country’s internal affairs.”

What the Cuban regime sees in Iran is a reflection of its own frustration with the world’s superpower. Cuba-U.S. tensions peaked in the 1960s, but the U.S. embargo continues to severely impact its economy. Since then, Cuba has had two options: either find willing partners like Iran, or appease U.S. administrations that have promised an end to the embargo on the condition that Cuba stop its human rights abuses. Choosing the former, Havana not only found economic assistance, but also a power keen on defending its “sovereign rights” on the world stage.

Bilateral relations and cooperation

Cuba-Iran relations today can be described as transactional. Iran’s theocratic form of governance does not bother Cuba; as Castro stated on several occasions, there is “no contradiction between revolution and religion.” As a result, the two countries have a long history of economic, scientific, military, security, intelligence, and diplomatic cooperation.

Interestingly, the latest data reported in 2018 indicates that Cuba exported a puny $97,000 to Iran, while the latter sent just $60,000 in return. The main products exported were antibiotics and mill machinery, respectively. While their trade volume is quite low, the 17th Session of the Cuba-Iran Intergovernmental Commission, held in Havana in January 2019, saw the signing of a memorandum of understanding between the Cuban Center for the Promotion of Foreign Trade and Investment and the Iranian Trade Promotion Organization. During the signing, Cuban Minister of Foreign Trade and Investment Rodrigo Malmierca asserted that, “The challenge of the commission is to raise economic commercial exchange to the same level as the excellent political ties between the two countries.”

In the same session, Cuba and Iran drafted a memorandum of understanding between Cuba’s Finlay Institute of Vaccines and Iran’s Pasteur Institute. This past July, Iranian state news outlets reported that the institutes have agreed to the “transfer of technology for the production of [the] Soberana-2 vaccine in Iran.” A month later, Alireza Biglari, director of the Pasteur Institute of Iran, was awarded the Carlos J. Finlay Award “for his contribution to biotechnology, teaching, and scientific activity in both countries.”

Cuba and Iran have also cooperated in the fields of defense, military, and intelligence. The most recent widely reported case of intelligence cooperation was in 2003, following Cuban jamming of U.S.-based satellite broadcasts to Iran. However, many experts confirm that Cubans “represent an on-the-ground highly familiar and capable intelligence service that can supply access, insight, and support to others who also have interests here” today, referencing Iran, Venezuela, and other nations hostile to the U.S. In April 2020, the Biden administration urged Cuba and Venezuela to turn away two Iranian warships “believed to be carrying arms intended for transfer to Caracas,” illustrating Tehran’s military ties to Havana as well as U.S. fears of encroachment into its hemisphere. Cuba’s geostrategic location vis-à-vis the U.S. attracts foreign powers pursuing an anti-U.S. foreign policy. These regimes, including Iran, seek to benefit from intelligence cooperation agreements with Cuba, which is located only 90 miles away from Key West, Florida.

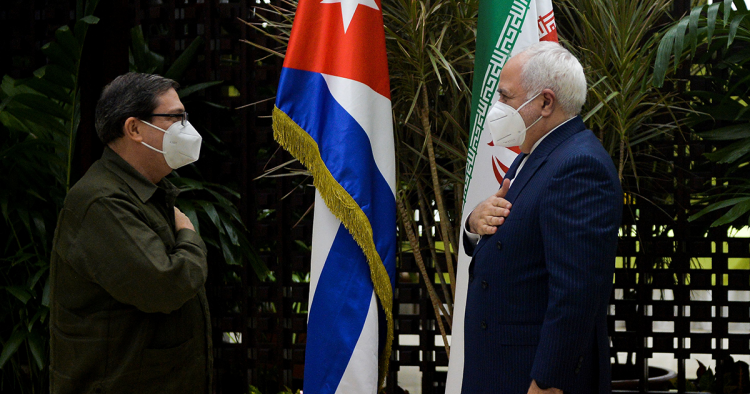

Cooperation in the diplomatic sphere is also perceived by the U.S. as a threat. Recently, Cuba and Iran convened to await the result of the 2020 American elections. Iran’s then-Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif accused the U.S. government of engaging in “economic terrorism” against Iran and Cuba during the informal event. On the same note, Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez thanked his Iranian counterpart for the position his country maintains against the U.S. embargo on Cuba. Rodriguez also defended Iran’s right to the use of peaceful nuclear energy.

At the moment, 12 agreements are currently in effect for the exemption of diplomatic and service visas, and despite their low volume of trade, cooperation continues to expand in the defense, intelligence, and health spheres and relations recently hit a significant milestone with their collaboration on the Soberana-2 vaccine. While Cuba may achieve some level of stability from relations with Iran, Havana-Tehran ties will continue to impede the normalization of U.S.-Cuba relations. Cuba eagerly welcomed the prospect during the Obama presidency, but as Tehran continues to defend Havana’s human rights abuses, it gives Cuba a diplomatic safe haven at the expense of the country’s economic and civil stability.

Marzia Giambertoni is a research assistant with MEI’s Iran Program and a senior at Brown University, where she is concentrating in International and Public Affairs under the security track and Economics. The views expressed in this piece are her own.

Photo by YAMIL LAGE/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.