Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is in desperate need of good news. He faces a host of problems at home, including a steadily deteriorating economic situation. The Turkish lira tumbled to a record low last week despite officials’ efforts to prop it up with massive sales of the country’s rapidly dwindling foreign-currency reserves. Economists estimate that the central bank spent $65 billion of its foreign-currency reserves in the first six months of this year to defend the lira, far more than the $40 billion it spent last year, and as of mid-August its remaining reserves were down to just $45.4 billion. Erdogan’s problems are compounded by high unemployment, a resurgent coronavirus pandemic, and breakaway political parties that could eat into his already waning support among conservatives.

In the past, when the situation at home looked dire, foreign policy crises came to his rescue. To distract attention from his domestic woes, Erdogan launched several military incursions into Syria, giving him a bump in support in the polls of a few points, albeit only temporarily. But this time around the foreign policy front presents problems for Erdogan, rather than solutions. After a deadlock in Syria, Turkey has intervened militarily in Libya and pursued an aggressive strategy in the eastern Mediterranean. Turkey touted its Libya intervention as a game changer and vowed to help the UN-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) take the central Mediterranean port of Sirte, the gateway to Libya's eastern oil fields and the key al-Jufra airbase to the south. But the fighting has stalled around these towns and the GNA recently announced a cease-fire, which has since been rejected by Gen. Khalifa Hifter. Turkey’s eastern Mediterranean policy has failed to change the status quo and drawn warnings from its NATO allies and the European Union.

A discovery in the Black Sea

In the midst of the challenging dynamics on both the home and foreign policy fronts, Erdogan ordered the Turkish drillship Fatih to begin exploring for offshore energy resources in the Black Sea. A month after the ship began its search, the good news Erdogan had been waiting for arrived. “God has opened the door to unprecedented wealth for us,” said an enthusiastic Erdogan as he announced that Turkey had made its biggest-ever discovery of natural gas, located off the coast of Zonguldak Province in the Black Sea. He promised that gas from the 320-billion-cubic-meter (bcm) deep-sea find would reach consumers in 2023, the 100th anniversary of the birth of the modern Turkish republic. To put this into perspective, Turkey's proven gas reserves were less than 5 bcm in 2019. Speaking aboard the Fatih, Turkey’s finance minister and Erdogan’s son-in-law, Berat Albayrak, who has been the target of the opposition due to his handling of the economy, said “the discovery would help reduce Turkey’s widening current-account deficit by addressing the country’s high annual energy import bill.”

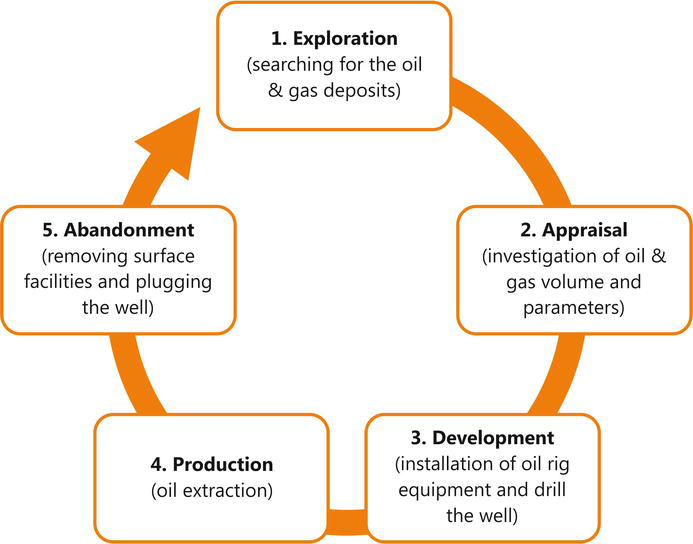

The opposition parties rushed to congratulate Erdogan. Domestic and international analysts were quick to tout the find as a watershed that would significantly reduce Turkey’s energy dependence on Russia. But industry experts are skeptical. Ankara opted to be somewhat discrete about the technical details of the discovery, revealing merely the reserve estimates and approximate area of the finding, which raised questions about the feasibility of the discovery. According to the official statements, the TPAO, the state-owned energy company behind the discovery, broke the news and forecast the reserves after drilling only one exploration well: Tuna 1. Although a single exploration well could be sufficient to make the discovery, determining its size usually requires a more comprehensive approach. This suggests that the company is only in the initial stages of the process and it needs to do further drilling to determine the actual size of the discovery. The life cycle of a conventional oil and gas field goes through multiple steps ranging from exploration to actual production (see below), and the TPAO will have to drill appraisal wells to determine the exact amount of technically recoverable reserves.

Conventional oil and gas field life cycle

What impact will it have?

There are questions as to whether the find is a game changer for both Turkey’s own energy aspirations and its ties with Russia. Turkey is an energy dependent country and historically has relied heavily on Russia to supply its natural gas. That has changed recently, however, with imports from the country falling by 41.5 percent in the first half of the year to 4.7 bcm. As imports from Russia have dropped, those from Azerbaijan have boomed, up 23.4 percent to 5.44 bcm. Turkey has also ramped up its liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports, increasing by 44.8 percent to 10.3 bcm in January-June 2020, with cargoes coming from the United States, Nigeria, Algeria, and Qatar, as well as Russia. It has added LNG import facilities in the east Mediterranean and the Black Sea basins. Moscow now ranks as the fourth-biggest supplier of gas to Ankara, down from the biggest last year.

A 320-bcm discovery is a modest one, similar in size to the Tamar field, the first significant discovery made in the eastern Mediterranean in 2009, off the coast of Israel. If the reserves are proven, Turkey could reduce its dependence on Russian gas further, but the current discovery is not sufficient on its own to realize the government’s dream of turning Turkey into an energy hub. It would, however, help to dramatically reduce the country’s import bill and would be enough to meet domestic demand for six to seven years. Turkey still needs to liberalize its domestic natural gas market and increase its gas storage capacity to become a hub.

The recent gas find will also do little to dramatically change Turkey’s current energy dynamics with Russia. The contracts Ankara signed with Moscow to import gas operate on the “take or pay” principle, which obliges Turkey to “either pipe in a certain number of volumes each year from the respective supplier or financially compensate it accordingly.” Turkish state-owned firm BOTAS can use the current find as a bargaining chip and ask Russia or other suppliers to lower their prices or waive the take-or-pay clause. For their part, the Russians do not seem particularly worried. Russian media covered Turkey’s recent find extensively, but Moscow has been in this business long enough to understand that the discovery is not a game changer. To put it in context, the total volume of probable reserves announced by Turkey is about twice the amount Russia’s Gazprom expects to export this year. Several Russian experts even argued that it would make more sense for Turkey to continue importing gas rather than developing its resources given the current low price environment.

Eye on the elections

But Erdogan insists the discovery is big news and just the beginning of the road to Turkish energy independence, and so far the opposition seems to be buying it. Opposition parties think that Erdogan’s “historic announcement” heralds early elections. Erdogan himself made it clear that this was an election investment when he said the field would start producing in 2023, when the next elections are due. This ignores the fact that the lead times for such deep-water reserves are long and the TPAO lacks experience operating such complex and costly projects, meaning it will have to rely on industry giants to handle the field development plan and schedule, increasing the cost.

Erdogan’s carefully choreographed announcement, which he dropped a hint about a few days ahead of time, has not produced the expected results. His comment earlier in the week that he had good news to deliver on Friday lifted the Turkish lira from the week’s record low, but it quickly lost the gains against the dollar after the details emerged. Economists warn that the find is not going solve Erdogan and Turkey’s economic woes. It certainly will not solve the country’s current-account deficit or address its dwindling foreign-currency reserves. And the Turkish electorate’s economic concerns seem too urgent and extensive to be put at ease by a slight reduction in energy bills that may or may not materialize in several years’ time. All of which is to say, sooner rather than later Erdogan will have to pull another rabbit out of his shrinking hat.

Gönül Tol is the director of MEI's Turkey Program and a senior fellow with the Frontier Europe Initiative. Rauf Mammadov is a resident scholar on energy policy at MEI who focuses on issues of energy security, global energy industry trends, as well as energy relations between the Middle East, Central Asia, and South Caucasus. The views expressed in this piece are their own.

Photo by Mustafa Kamaci/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.