The MENA and Southeast Asia have undergone and continue to undergo massive political transitions. Differences in the process and outcomes of their transitions can be viewed through the lens of a “civil society infrastructure.” This essay series explores the roles and impact of civil society organizations (CSOs) in these two regions during the transition and pre-transition periods as well as in instances where the political transition is completed. Read more ...

Political and economic transitions are seldom, if ever, compartmentalized processes, insulated from regional and global influences. On the contrary, they are often informed and shaped by exogenous forces and the policies of external actors, including states and international organizations. How can external actors develop interventions that are more likely to be well received and thus support transitions to democracy?

Last fall I took part in a conference on “Europe and the Middle East & North Africa: Building Bridges, Mapping the Future”[1] hosted by the Kuwait Program at SciencesPo in Paris. In his keynote speech, Paris School of International Affairs (PSIA) founder and Special Representative and Head of the UN Support Mission in Libya Ghassan Salamé posed the question, “Is the ‘Europe-MENA’ strategic bond a myth?” The conference raised questions about internationalism and yielded important insights about the importance and practice of public diplomacy.

My contribution at the conference was to speak about public opinion examining the view of Europe from the Arab world. Based on surveys conducted by the Arab Barometer[2] and the Transitional Governance Project[3], I found that there is a deep reservoir of goodwill in Arab countries toward Europe. In all eight Arab countries in which questions about Europe had been asked, citizens regarded the European Union more positively than almost every other country or bloc, including the US. This surprising finding holds important lessons for the public diplomacy benefits of promoting internationalism and the costs of unwanted interventionism.

Survey Data on Attitudes toward Europe

Surprisingly, few survey questions exist to might offer insights into how Arab citizens see Europe in relation to other regions. Questions about views of Europe were included in a nationally representative survey of 1200 Libyans I conducted with Ellen Lust and JMW Consulting in 2013 as part of the Transitional Governance Project with funding from the National Democratic Institute. The Arab Barometer also asked questions about Europe in Wave 4, a series of surveys conducted in 2016 among nationally-representative samples in Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, and Tunisia. And Wave 3, which was conducted in Algeria, Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, Yemen, Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, between 2012 and 2014, asked important questions about the types of US engagement Sudan, Iraq, Libya, and Kuwait, citizens welcomed. These surveys provide some of the few clues available concerning how Arab citizens see Europe in relation to other countries and international organizations.

Libya: The Post Arab Spring Environment

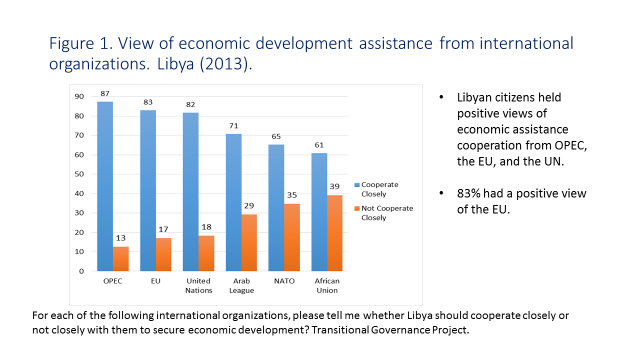

In Libya in 2013, as part of the Transitional Governance Project, we asked citizens to state whether they would like to cooperate closely with different international organizations to achieve economic development in their country (Figure 1). Libyan citizens held more positive views toward the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) than any other international organization included in the questionnaire. Eighty-seven percent of Libyans stated that they wanted to cooperate closely with OPEC. Citizens also saw cooperation with the European Union and the United Nations as highly desirable, with 83 and 82 percent holding this view, respectively.

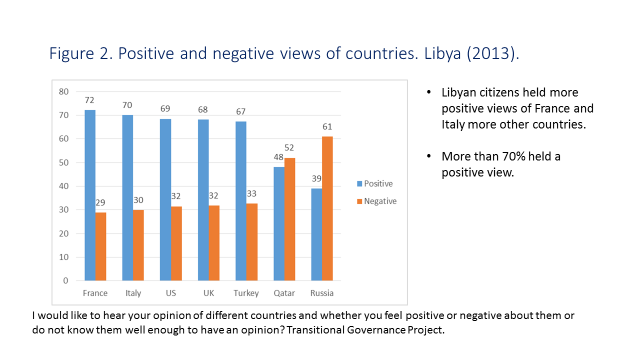

Libyans held warmer views of France and Italy than Russia and Qatar (Figure 2). Seventy-two percent of Libyans saw France in a positive light, while 70 percent saw Italy in this way. Libyans also held positive views of the US (69 percent), despite its central role in the NATO intervention. Similarly, 68 percent had a positive view of the UK and 67 percent toward Turkey. Only 48 percent held a positive view of Qatar and 39 percent did in the case of Russia, the least popular actor.

Libyans saw other regional organizations, including the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), in a less positive light. Seventy-one percent regarded the Arab League in positive terms, compared to 65 percent for NATO and 61 percent for the African Union. The latter is perhaps not surprising, given that NATO had recently intervened in Libya’s civil war by enforcing a no-fly zone. The US-led NATO intervention in Libya was welcomed by many Libyans at the time, though certainly not by all. This was reflective of the early optimism both among Libyans as well as internationally about the prospects for transition to democracy. As of 2013, 81 percent of Libyans were optimistic or very optimistic about the future of their country,[4] while only 19 were pessimistic. This optimism was already beginning to fade by 2014 when the Arab Barometer was fielded in Libya.

Libyans saw other regional organizations, including the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), in a less positive light. Seventy-one percent regarded the Arab League in positive terms, compared to 65 percent for NATO and 61 percent for the African Union. The latter is perhaps not surprising, given that NATO had recently intervened in Libya’s civil war by enforcing a no-fly zone. The US-led NATO intervention in Libya was welcomed by many Libyans at the time, though certainly not by all. This was reflective of the early optimism both among Libyans as well as internationally about the prospects for transition to democracy. As of 2013, 81 percent of Libyans were optimistic or very optimistic about the future of their country,[4] while only 19 were pessimistic. This optimism was already beginning to fade by 2014 when the Arab Barometer was fielded in Libya.

Attitudes toward Europe across the Arab World

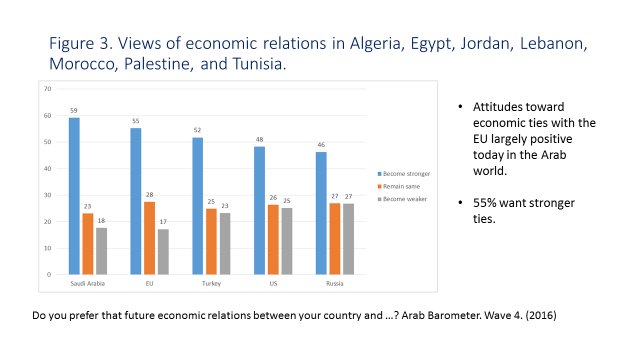

The Arab Barometer asked nationally-representative samples of Arab citizens in Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, and Tunisia in 2016 whether they wanted their economic relationships with other countries to become stronger, remain the same, or become weaker. In these seven Arab countries, attitudes toward economic ties with the European Union were overwhelmingly positive with 55 percent of citizens in all of these countries wanting stronger ties, 28 percent wanting similar ties, and 17 percent wanting weaker ties (Figure 3). Only Saudi Arabia had a warmer perception than the EU with 59 percent of Arab citizens wanting stronger ties, 23 percent wanting similar ties, and 18 percent wanting weaker ties. Views of Turkey were also favorable with 52 percent of citizens in all of these countries wanting stronger ties, 25 percent wanting similar ties, and 23 percent wanting weaker ties.

The US and Russia, in contrast, were seen as less appealing economic partners than Saudi Arabia, the EU, and Turkey. This is striking for American policymakers. Only 48 percent of Arab citizens wanted stronger ties with the US, just two percent higher than for Russia, at 46 percent.

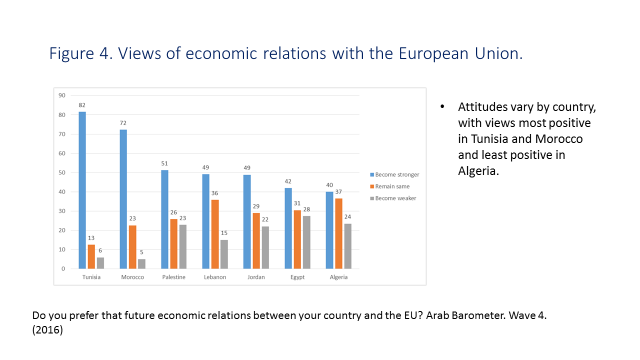

Yet attitudes across the seven Arab countries varied dramatically (Figure 4). The most favorable views of the EU were in Morocco and Tunisia, while the least favorable were in Algeria, which was colonized by France for 130 years. Fully 82 percent of Tunisians and 72 percent of Moroccans desired stronger ties with the EU while about half of all Palestinians, Lebanese, and Jordanians did. Only 42 percent of Egyptians and 40 percent of Algerians would like to see stronger economic ties with Europe.

Yet attitudes across the seven Arab countries varied dramatically (Figure 4). The most favorable views of the EU were in Morocco and Tunisia, while the least favorable were in Algeria, which was colonized by France for 130 years. Fully 82 percent of Tunisians and 72 percent of Moroccans desired stronger ties with the EU while about half of all Palestinians, Lebanese, and Jordanians did. Only 42 percent of Egyptians and 40 percent of Algerians would like to see stronger economic ties with Europe.

The positive views that Tunisians hold toward Europe are striking given that Europe, and France in particular, supported the Ben ‘Ali regime. But European countries have generally had strong productive relationships of trade and tourism and no European country has generally directly intervened in either country since their independence from France.

The positive views that Tunisians hold toward Europe are striking given that Europe, and France in particular, supported the Ben ‘Ali regime. But European countries have generally had strong productive relationships of trade and tourism and no European country has generally directly intervened in either country since their independence from France.

The negative views of Europe among Algerians also stand out. Many Algerians see France as the fifth column[5] in their domestic politics. And colonial wounds have not healed. Even though President Macron[6] has taken more concrete steps than any other French president to confront the difficult colonial past — and even though he recently admitted that France tortured and executed members of the Algerian resistance during Algeria’s revolutionary war — France has yet to apologize for colonizing the country.

Egyptians also held fairly negative views of Europe, while Libyans held a positive view of their former colonizer, Italy, according to the Transitional Governance Project. The negative views that Egyptians hold of the EU is striking and merits further exploration. It is perhaps indicative of the differences between European and Egyptian leaders, as well as other Arab leaders,[7] on human rights, democracy, and press freedom.

Tailoring Engagement Strategies through Public Diplomacy

Whether in Egypt or elsewhere in the region, it is critical to assess public opinion when developing a strategy to improve international relations and to support meaningful political and economic change,[8] which many see as essential to achieving long-term stability in the region.

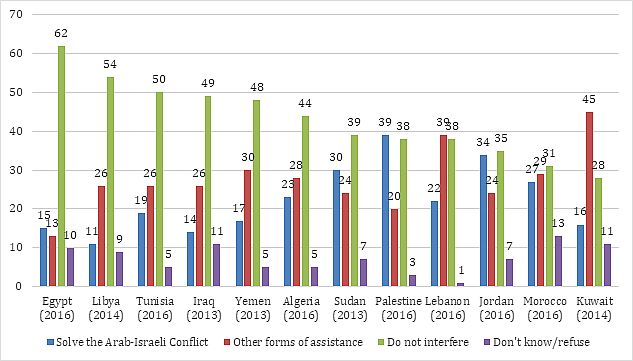

According to the Arab Barometer, Egyptians are among the least likely to desire US support for development in their country (Figure 4). In 2016, 62 percent did not want the US to intervene, while 15 percent wanted assistance to solve the Arab-Israeli conflict and 13 percent wanted support for other objectives, which included economic development (7 percent), women’s rights (2 percent), and promote democracy (4 percent). This contrasts with much lower, though not insignificant, levels of opposition to support with development objectives in Jordan (35 percent), Morocco (31 percent), and Kuwait (28 percent). Importantly, in some countries, citizens are more interested in support for peacemaking in the Arab-Israeli conflict (Egypt, Sudan, Palestine, and, Jordan), while in others, economic development, democracy promotion, and women’s rights are more important (Libya, Tunisia, Iraq, Yemen, Algeria, Lebanon, Morocco, and Kuwait).

Figure 5. Desired U.S. Assistance Source: Arab Barometer, Wave 3-4. (Not asked in Wave 1-2).

Source: Arab Barometer, Wave 3-4. (Not asked in Wave 1-2).

Question wording: “What is the most positive policy that the US can follow in our region? Promote democracy; Promote economic development; Contain Iran; Solve the Arab-Israeli Conflict; Promote women’s rights; The US shouldn’t interfere.” (‘Other forms of assistance’ includes Promote democracy; Promote economic development; Contain Iran; and, Promote women’s rights).

Conclusions

Available data suggest that to a greater extent than toward the US, there is a reservoir of goodwill in the Arab world toward Europe, highlighting the benefits of Europe’s internationalism. Goodwill toward Europe appears to be deeper in countries with limited, unwanted interference in Arab politics.

The diversity in responses across countries (and time) in terms of whether support is wanted and what types of engagement are welcome underscores the importance of efforts to inform foreign policy and direct diplomacy with public diplomacy—listening to citizens through person-to-person initiatives and consulting public opinion surveys. Other less politicized forms of engagement, including educational exchange and trade and investment, may need to be priorities in countries such as Egypt where efforts to directly strengthen democracy, freedom of expression, and women’s rights are viewed as unwanted interference by a larger segment of the population. Taking positive steps toward addressing colonial legacies, listening, and engaging constructively through economic ties and education exchanges are also critical.

If extra-regional contributions to democratic consolidation are to be meaningful and effective, then the population must be receptive. And the types of support that the population desires must be taken into account. Engagement must be complemented by more than mere acquiescence by the local population, but by an active effort to listen to and offer the forms of assistance and support that are seen as helpful by Arab citizens. Effective public diplomacy should improve goodwill, and it will also likely support more effective foreign policy.

[1] “2018 Conference on Europe and the Middle East & North Africa: Building Bridges, Mapping the Future,” SciencesPo Kuwait Program, October 3-5, 2018, https://www.sciencespo.fr/kuwait-program/europe-mena-conference-2018/.

[2] Arab Barometer, http://www.arabbarometer.org/.

[3] Transitional Governance Project, http://transitionalgovernanceproject.org/contributors/.

[4] Lindsay Benstead, Ellen M. Lust, and Jakob Wichmann, “It’s Morning in Libya: Why Democracy Marches On,” Foreign Affairs, August 6, 2013, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/libya/2013-08-06/its-morning-libya.

[5] “Why France won’t officially apologize for its crimes in Algeria?” Quora, https://www.quora.com/Why-wont-France-officially-apologize-for-its-crimes-in-Algeria.

[6] “Macron rights a historical wrong in admitting French torture in Algeria,” France 24, May 13, 2019, https://www.france24.com/en/20180914-macron-maurice-audin-historical-wrong-french-torture-algeria.

[7] David M. Herszenhorn, “EU, Arab leaders draw lines in the sand,” Politico, February 25, 2019, https://www.politico.eu/article/egypt-abdel-fattah-el-sisi-capital-punishment-death-penalty-europeeu-arab-leaders-draw-line-in-the-sand/.

[8] Adel Abdel Ghafar, “Egypt’s long-term stability and the role of the European Union,” Brookings Institution, March 1, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2018/03/01/egypts-long-term-stability-and-the-role-of-the-european-union/.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.