Originally posted July 2010

This paper describes a collaborative venture in online education between a global e-university and one located in the Middle East, and outlines some of the difficulties encountered on the way to this successful partnership. Academia itself can by quite conservative in the adoption of new pedagogical approaches to learning, and online delivery of programs is certainly no exception to this. The incidence of purely or primarily online programs in the Middle East is low in comparison with the US and Australia, although, as will be seen, the developmental changes are rapid - there is, for example, a wealth of work on ICT-supported face-to-face degree programs.

The pace of change in the Middle East can be evidenced in a number of ways. First, there is a growing recognition that online education should be seriously considered, as evidenced by the many conferences on this issue held in the region. Second, the past decade has seen the birth of universities set up specifically for online education (e.g., Hamdan Bin Mohammed e-University (HBMeU), set up in 2002 as the region’s first virtual institution) while U21Global and the Syrian Virtual University, both in Dubai’s Knowledge Village, and, more recently, the strongly marketed University of Liverpool/Laureate, have been developing their visibility as a provider of online degrees. The typical advantages of online education apply to the Middle East as much as anywhere, but flexibility with regard to study time, geographically remote access, and the community of global students may be seen as especially important for students there.

Figures for growth of e-learning in the Middle East range widely, but are generally very high (e.g., predicted compounded annual growth rates of 26% for UAE[1]). The UAE 2020 Education Vision second five-year plan argued for a need to update curricula and pedagogical methods through the use of technology, amongst other tools. HBMeU recently held the third annual forum on e-learning excellence in the Middle East, and led the launch, together with UNESCO, of the Middle East e-Learning Association. Indeed, most of the innovations in the direction of online education have been reported in the UAE and Saudi Arabia. It is clear, however, that much thought is being given to the development of e-learning elsewhere. For example, the University of Bahrain has held international conferences on the role of e-learning in supporting knowledge communities, and the Sultan Qaboos University has run similar international meetings - a series of Omani Society for Educational Technology conferences in Muscat.

The development of online education in the Middle East, however, is not easy, as will be indicated by the case study of this paper. There is, as elsewhere, a traditional resistance to online education, which could be a combination of any of the following:

- There is a belief among those not familiar with the area that face-to-face education is of better quality;

- The supply of campus-based university programs is high, and there is therefore no need for supplementing this by offering online education;

- There is an overall lack of understanding of the nature, let alone the advantages, of online education;

- There is a perceived preference for blended programs (some face-to-face components such as monthly or weekly meetings/seminars), perhaps because of the perception that online education does not provide for good social networking and interaction;

- The bureaucracy involved in setting up online education is daunting, leading to difficulties in getting online education degrees accredited, despite the strong government strategy to engage in such development.

Case study

During early 2008, HBMeU joined hands with Singapore-headquartered U21Global to create joint programs for the Middle East. It was perhaps for the first time that two online institutions had come together to leverage each other’s strengths. U21Global had vast experience in creating and delivering cutting-edge e-learning programs globally, while HBMeU (then called eTQM College) had pioneered e-learning in the Middle East region. HBMeU and U21Global wanted to create two joint programs - Master of Project Management and Master of Management in Entrepreneurial Leadership (MMEL), with, in each of the programs, a number of modules developed by either side.

There are three ways in which institutions and/or degree programs may be accredited in the UAE. Universities that are established by Royal Decree may quality assure their own programs, and no further independent accreditation requirements must be met. For other universities, including overseas universities that have been set up in the Emirates, the Commission for Academic Accreditation (CAA) provides the required external quality assurance (QA) function. However, for those institutions operating within the Free Zones of Dubai, an alternative body, the University Quality Assurance International Board (UQAIB) of the Knowledge and Human Development Authority was set up to ensure the near equivalency of the institutions and/or programs to those of the home campus. The CAA system essentially accredits institutions against local standards. The UQAIB, as is implied above, accredits more on the basis of foreign national standards, and may therefore be seen as more flexible in its requirements. The UQAIB system is well described elsewhere[2]; in this case study, the joint program between U21Global and the local HBMeU required that accreditation be sought through the CAA.

The CAA, running under the Ministry for Higher Education and Scientific Research, mandates that an institution applying for accreditation must have its campus located in the country with infrastructure to support conventional face-to-face learning in physical classrooms. The Ministry does not make any exceptions to this rule for e-learning institutions. This position was exemplified by the CAA’s reluctance to accredit a completely online program. The insistence upon having some face-to-face sessions in every course in conjunction with synchronous technologies perhaps reflected the traditional pedagogical approach of face-to-face delivery of lectures by professors. While there is a concentration in the review process on describing learning outcomes down to a detailed level of granularity (a part of the detailed documentation required by CAA), an outcomes-oriented approach clearly does not take precedence over the mode of delivery.

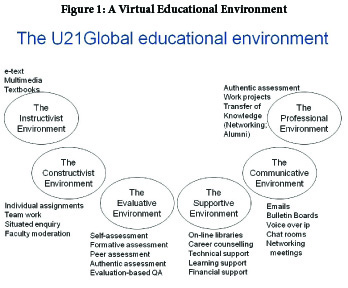

A team of experts visited the HBMeU campus in connection with the accreditation process for the proposed programs. The team comprised two senior professors from the UK and one from the US, accompanied by a Commissioner appointed by the Ministry. All four of them are renowned experts in their respective fields and hail from prominent traditional universities, although they would not be well known as experts in, or advocates for, online education. Some of the suggested online assessment components (that are successfully used by online institutions world-wide and have gained credibility with the online education community, students, and specialist online accreditation agencies) for the courses, were not acceptable to the team. The holistic online environment created by U21Global for its completely online MBA program (Figure 1), which has won awards for its design, failed to convince the team of experts.

Figure 1: A Virtual Educational Environment

The recommendations report received from the Ministry in January 2009 for revising the proposed programs was comprehensive and provided some useful suggestions for the improvement of the curriculum. However, some other requirements for change were so radical in nature that they would alter the very scope and target audience of one of the two programs, namely the MMEL. The MMEL program initially intended to focus upon entrepreneurs from a variety of industries, including family businesses. However, despite the program viability surveys conducted earlier in Dubai to understand the needs of the prospective students for the program, the review report required the universities to reduce the scope to only entrepreneurs starting small businesses. In this connection, the report suggested that a number of proposed courses be replaced by new ones focusing exclusively on small business entrepreneurship. The Ministry eventually required two more revision cycles before accrediting the two programs, after 1.5 years of effort.

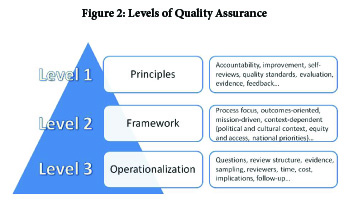

Figure 2: Levels of Quallity Assurance

HBMeU was the first e-university of its kind in the region - innovators or even early adopters have to do much more to explain the unique character of their provision to authorities than traditional providers. In a sense, this is a knowledge exchange process, with both the accreditor and the institution needing to understand each other’s respective positions.

Conclusion and the Way Forward

E-learning is growing rapidly from a small base in the Middle East region. Even corporate education is changing classrooms into webinars. The establishment of HBMeU in Dubai is a testament to the fact that the government is aware of the importance of nurturing different formats of higher education. The UAE can, and often does, serve as a torch-bearer for the region, which makes its understanding of tomorrow’s pedagogy and modes of delivery even more important.

Accreditation issues across borders are complex, but those involving online programs doubly so. In online education, the same program may be offered around the world, and thus be subject (or not) to the many different national QA systems in the place of residence of each of the students. In some cases, the provider may not even have a national “home,” and, in some cases, it may not be possible to validate whether there are students resident in a particular country.

The first of the present authors[3] has argued that delivery mode is also part of the context in which the QA system should be dependent. So, for example, e-learning QA would concentrate on some criteria, at levels 2 and, certainly, level 3 of Figure 2, that would not be prioritized in a more traditional face-to-face educational environment (such as the need for higher levels of student support and ways of coping with lower student motivation). There is a strong need for sensitivity to these issues in local accreditation systems, as shown by this case study. Relying on a framework based on traditional delivery and pedagogy can slow local development unless there is a clear understanding of the emerging research in this area.

The message from this case study is that the accreditation route is not easy for non-traditional overseas providers if a partnership arrangement is preferred. This difficulty can have an inhibitory effect on local tertiary development through the benchmarking and knowledge exchange that come from educational collaborations. The UQAIB has to be more open and flexible, as its standards are aligned to those of the home country of the institution being accredited, thus operationalizing the UNESCO/OECD principles for cross-border higher education accreditation. However, it could be argued that the national context (e.g., values and goals of education, social and political values, resources) should be aligned with the goals of the QA system. CAA takes into account national issues, such as national priorities for curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment. If the review process is such that it ensures an excellent fit between the nation’s needs and the institutional offering, then this is an appropriate mode of QA. Unfortunately, this has to be balanced against the tensions that can result from institutions that have a different set of values for constructing their own educational provision, and leads to deep questions about whether those values can be sacrificed.

[1]. Data provided by Madar Research Group.

[2]. W. Rawazik and M.I. Carroll, “Complexity in Quality Assurance in a Rapidly Growing Free Economic Environment: A UAE Case Study,” Quality in Higher Education, Vol. 15, No. 1 (2009), pp. 79-83.

[3]. J.A. Spinks, “Emerging Issues in the Quality Assurance of e-learning Programmes and Institutions,” Keynote address to the I-CODE 2006 Conference, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman, March 27, 2006.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.