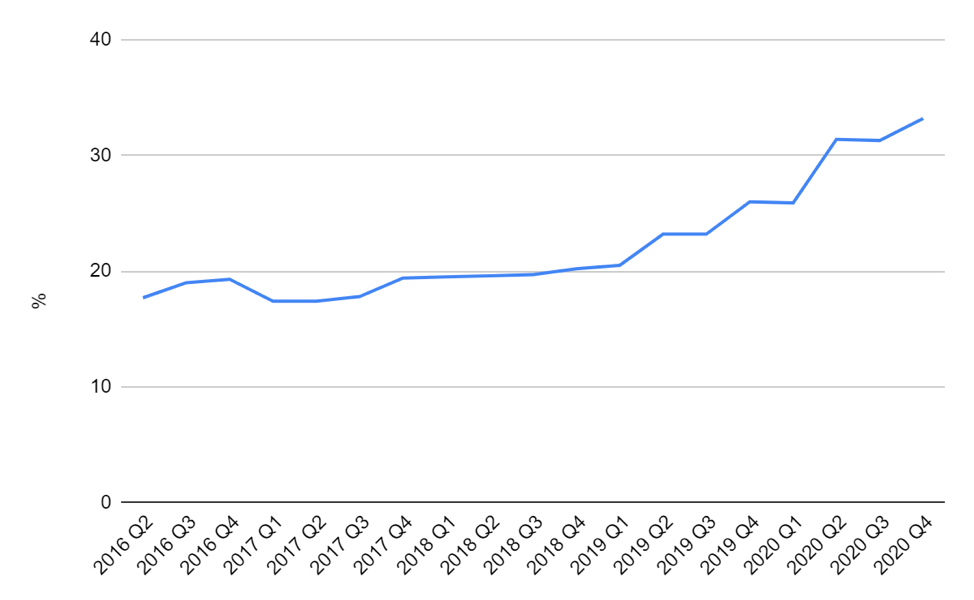

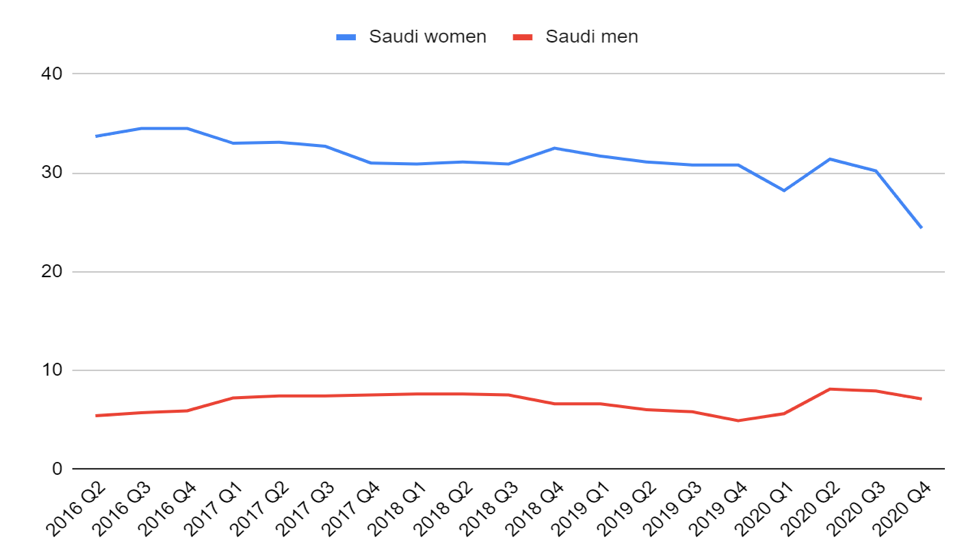

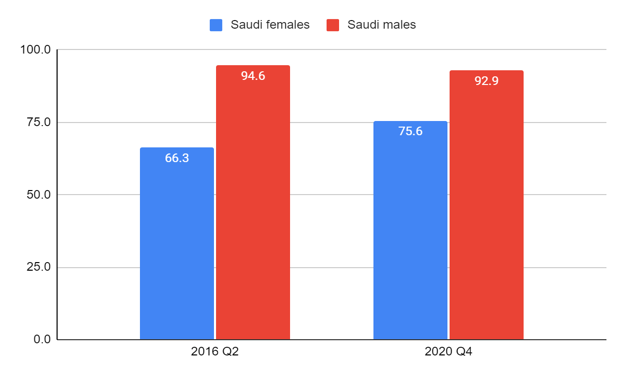

In the past few months, several articles have been written on the significant rise in the Saudi female labor force participation rate (LFPR) from 17.7% in Q2, 2016 to 33.2% in Q4, 2020 (see Figure 1). Interestingly, this increase in female LFPR was not coupled with a rise in unemployment, which often occurs when workforce participation rises for a particular group. In fact, the unemployment rate among female nationals declined to its lowest level in four years, at 24.4% in Q4, 2020 (see Figure 2). However, it still remains over twice as high as that for male nationals. Another positive labor market indicator, albeit one receiving little attention from analysts, is the significant change in the employment rate among Saudi women (see Figure 3). The employment rate, which is defined in Saudi Arabia as the share of employed individuals to the total labor force of the same group, rose from 66.3% in Q2, 2016 to 75.6% in Q4, 2020.1 In other words, Saudi women not only increased their share in the workforce, but were also able to gain jobs once they entered the labor force. Unfortunately, however, during the same period the employment rate for Saudi men declined slightly from 94.6% to 92.9% (see Figure 3).

Previous analyses explaining the increasing female LFPR have primarily focused on how removing supply-side barriers contributed to this impressive increase. Indeed, Saudi Arabia passed seven policy reforms in 2020 alone and was recognized as a top performer, according to the World Bank report “Women, Business, and the Law 2020.” These policy changes range from economic to legal reforms, such as making it illegal to fire pregnant women, protecting women from workplace harassment, and removing all barriers related to access to credit and other financial services (see Appendix).

Removing regulatory labor constraints that limited the mobility of females in the past and introducing supply-side enablers have both played a crucial role in the increasing female LFPR. However, focusing primarily on the supply side is not sufficient to explain the whole story. Specifically, this article explores another factor that indirectly contributed to this positive trend: the tax on foreign workers and their dependents.

Foreign worker and dependent tax

First, the Ministry of Social Development and Human Resources (formerly known as the Ministry of Labor) introduced on July 1, 2017 a monthly $26 tax on every dependent sponsored by a foreign worker in Saudi Arabia. By 2018, the tax on foreign dependents increased to $53 per month. Additionally, firms employing more foreign workers than nationals were also required to pay a monthly tax of $106 for every foreign worker.As of 2020, foreign workers were required to pay approximately $107 for their dependents, while firms were taxed monthly at $213 per worker if their workforce has more expats than nationals.

Reducing the cost gap between national and foreign labor

A unique and long-standing characteristic of labor markets across the Gulf is the remarkable cost gap between national and expat workers. Saudi Arabia, however, has taken several steps to make it less attractive for private firms to hire low-cost foreign labor, as it continues to face rising female and youth unemployment among nationals. A 2018 IMF paper argues that the private sector wage gap between national and expat workers is both significant and makes nationals more expensive to hire by private firms.

The implementation of the 2017 tax on foreign workers and their dependents was specifically aimed at bridging the cost gap between nationals and foreign labor. This policy tool essentially makes it more expensive for firms to hire non-Saudis, addressing the issue of cost, which is a key driver behind firms’ hiring of foreign workers. The example below illustrates how the cost of hiring a foreign versus a Saudi national worker in 2020 is higher with the tax.

|

Nationality |

2020 hiring costs, without the foreign labor tax |

2020 hiring costs, with the tax on foreign labor |

|

National |

$800*2 |

$800 |

|

Foreign |

$400*3 |

$613*4 |

Despite receiving widespread criticism from the business community and some Shura Council members, the tax was in fact effective in reducing the cost gap between Saudi and foreign workers. More specifically, without the policy, it would cost firms twice as much ($800/$400) to hire a Saudi worker. However, with the tax it costs firms 1.3 times as much ($800/$613) to hire a national, as opposed to a foreign worker. In other words, the policy increased the cost of hiring a foreign worker by 53.2%.

Now back to our main puzzle: explaining the rapid rise in workforce participation among Saudi women. Previous reports on this trend restricted their analyses to a short time period: Q2 through Q4, 2020. Here, however, I will extend the analyzed period back to Q3, 2017, which is the first quarter capturing labor market changes after the introduction of the tax on foreign labor.

A major advantage of looking at a longer time period is that it allows us to get closer to finding evidence on whether the exodus of foreign labor from the private sector since Q3, 2017 has resulted in job gains for nationals, and particularly for Saudi women.

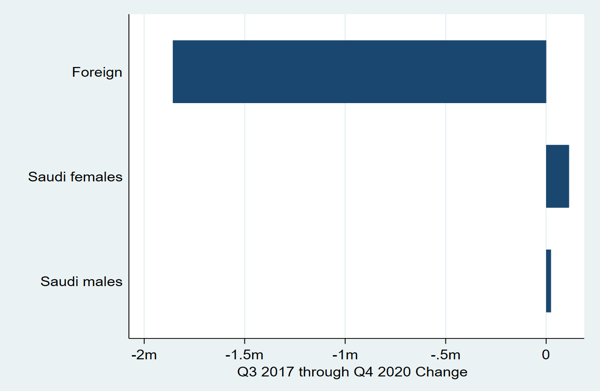

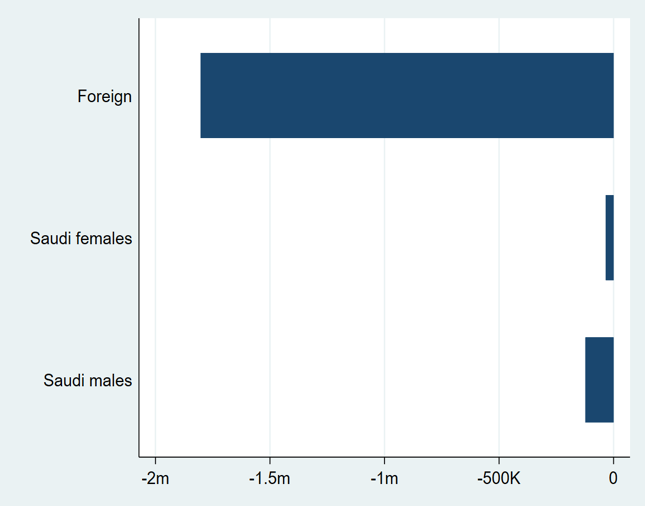

Since the introduction of the tax on foreign labor on July 1, 2017, the number of foreign workers in Saudi Arabia’s private sector has declined by 1,857,000, according to Q4 2020 Labor Force Survey (LFS) data from GASTAT. Over the same period, there was an increase of 24,000 Saudi men and 113,500 Saudi women in the workforce. In other words, approximately 1 Saudi worker joined the workforce for every 20 foreign workers who left the private sector since July 2017. This suggests that as the cost of low-skilled labor has increased, firms have found it more cost-effective and productive to pursue automation, although without access to the microdata it is difficult to say conclusively.

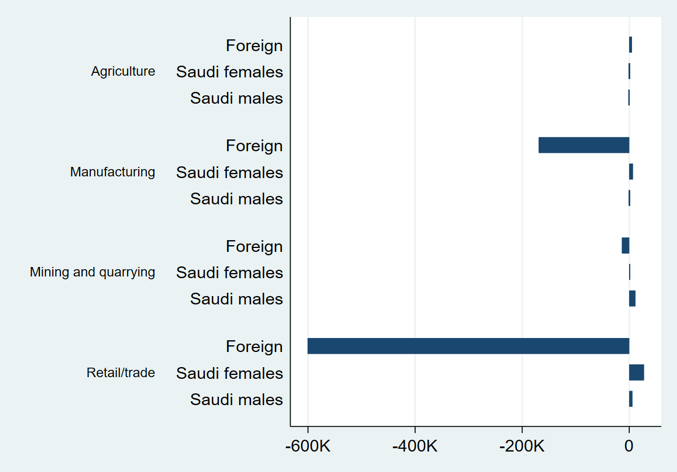

However, looking only at the change in the total number of workers is not sufficient. Therefore, next I will examine the changes in employment for foreign labor and nationals across the five largest economic sectors, between Q3, 2017 and Q4, 2020.

An in-depth look at within-sector employment changes provides some evidence that the exit of foreign labor from certain sectors, coupled with the rising cost of hiring expat labor and nationalization quotas, have all led firms to invest in hiring more Saudi workers, and especially Saudi women. However, the type of foreign workers who left Saudi Arabia’s labor force is not randomly distributed across the population of foreign labor. For example, 97.1% of foreign workers who left the country between Q3, 2017 and Q4, 2020 were employed in the construction sector. Additionally, 92% of expats employed in the construction sector were foreign men, often earning 1500 riyals or less per month. Indeed, administrative records from the General Organization for Social Insurance — Saudi Arabia’s private sector social security administration — confirm that the economic onus of the foreign worker tax mostly fell on this low wage group. Specifically, the number of foreign workers earning less than or equal to 1500 riyals per month declined from as many as 5,779,000 in Q4, 2017 to 4,337,000 in Q4, 2020 — a staggering drop of 1,442,000, or nearly 25%, in just three years.

One economic sector where nationals may have gained jobs, due to the exit of foreign labor, is retail/trade. The sector now employs around 600,700 fewer foreign employees than it did in Q3, 2017. At the same time, around 6,000 Saudi men and as many as 27,500 Saudi women have gained employment in the sector. Now, whether this gain in employment for nationals in the retail/trade sector is worth it, I leave that to policymakers and the reader to decide. Similar yet much smaller job gains occurred in the manufacturing sector, where there are 170,000 fewer foreign workers and 7,000 more Saudi women relative to Q3, 2017.

Turning next to the construction sector, it employed 1,803,000 fewer foreign workers in Q4, 2020, compared to Q3, 2017. Construction tells us a different story than the retail or manufacturing sectors. Specifically, lower employment of foreign labor did not translate into job gains for nationals. Indeed, there are 123,000 fewer Saudi males and 34,000 Saudi females employed in the sector today, compared to when the tax on foreign workers was implemented.

Nationalization quotas (Nitaqat)

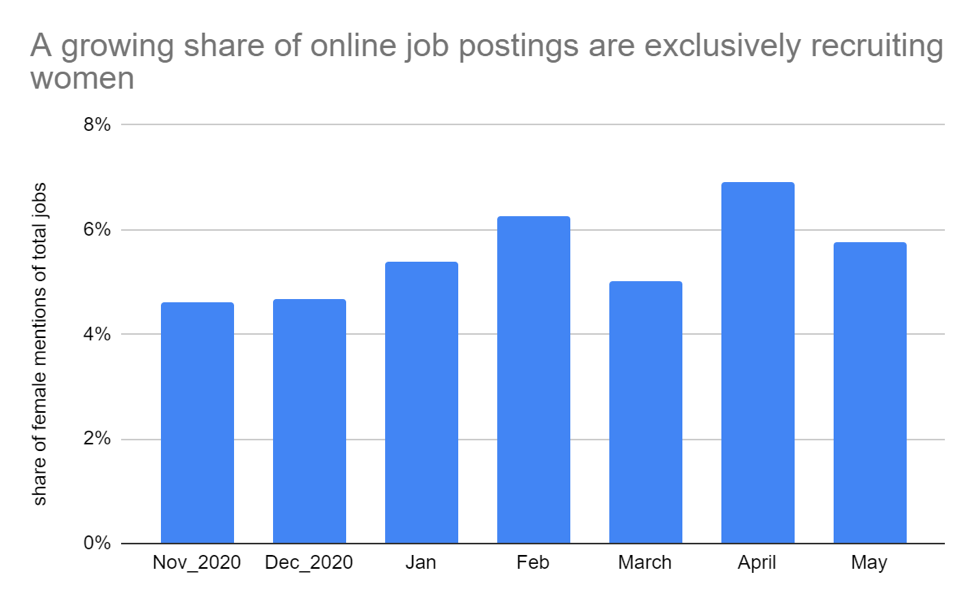

Additionally, we can’t talk about Saudi Arabia’s private sector without mentioning the nationalization thresholds it imposes on companies under the Nitaqat scheme. Recently, I have constructed and began tracking a proxy indicator of firms’ growing interest in exclusively hiring Saudi women, using a dataset of scraped job postings. The indicator measures the share of online job postings where phrases or words included in the job description or job titles suggest that the firm is exclusively hiring Saudi women, compared to the total number of online job postings each month.

The updated version of Nitaqat does not include any provisions favoring the hiring of Saudi women, as opposed to Saudi men. However, some private firms seem to believe that hiring female nationals gives them more Nitaqat points (i.e. toward achieving their nationalization quotas). This belief is partially due to an old provision in Nitaqat, whereby firms that hire Saudi women that work remotely will be counted as 1.25 points toward Nitaqat, so hiring four Saudi women working remotely was equivalent to five Saudi men. More recently, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development recognized that this inaccurate yet common belief might create employment barriers for Saudi men. As a result, the ministry announced in October 2020 that Saudi women are not counted more than Saudi men for Nitaqat purposes, despite what some have suggested on social media platforms.

In conclusion, it is difficult to explain the rise of LFPR for Saudi women without access to microdata from the LFS surveys. While prior analyses have mainly focused on supply-side constraints impacting Saudi women, the goal of this article was to look at other policies beyond those directly affecting Saudi women, including the introduction of the tax on foreign workers, which the findings suggest have contributed to the pattern of increasing female LFPR between Q3, 2017 and Q4, 2020. Relative to Q2, 2016, Saudi women not only increased their workforce participation but also their employment rate by approximately 14%, from 66.3% to 75.6% in Q4, 2020. Finally, whether these employment gains for Saudi women were due to newly private sector jobs, replacement of foreign labor, or the replacement of male nationals is difficult to answer without access to administrative data from the General Organization for Social Insurance and microdata from the LFS.

Meshal Alkhowaiter is a researcher at the World Bank Group focusing on labor markets in Arab countries. Prior to joining the bank, Meshal worked as a policy analyst for three years with the Saudi Ministry of Labor and as a research assistant with the Evidence for Policy Design (EPoD) focusing on Saudi Arabia’s labor market. The opinions expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by FAYEZ NURELDINE/AFP via Getty Images

Endnotes

- The employment rate in Q2, 2016 is not published directly in the LFS, but can be imputed using official figures in the survey. Specifically, I calculated the employment rate for Saudi women in Q2, 2016 by dividing total employed Saudi women/total Saudi women in the labor force: (830,000/1,252,000)*100=66.3%. The same equation was applied to impute the employment rate for Saudi men in Q2, 2016 as (4,172,000/4,409,000)*100=94.6%

- *This is assuming a firm pays the minimum wage for Saudi workers in the private sector, which may not always be the case.

- *This figure is approximated based on the average wage earned by foreign workers in the private sector, using GOSI’s administrative data: https://www.gosi.gov.sa/GOSIOnline/Open_Data_Library?locale=ar_SA

- *This figure is estimated based on the average wage of foreign labor of $400+$213 expat tax paid by firms in 2020=$613.

Appendix

|

Reform policy area |

Reform description |

Year |

|

Parenthood |

Saudi Arabia introduced paid paternity leave. |

2007 |

|

Equal pay |

Saudi Arabia mandated equal remuneration for work of equal value. |

2012 |

|

Marriage |

Saudi Arabia enacted legislation protecting women from domestic violence. |

2015 |

|

Mobility |

Women are allowed to obtain a driver's license. |

2018 |

|

Workplace |

Saudi Arabia enacted legislation protecting women from sexual harassment in employment. It also adopted criminal penalties for sexual harassment in employment. |

2019 |

|

Access to financing |

Saudi Arabia made access to credit easier for women by prohibiting gender-based discrimination in financial services. |

2020 |

|

Marriage |

Saudi Arabia began allowing women to be head of household and removed the legal obligation for a married woman to obey her husband. |

2020 |

|

Mobility |

Saudi Arabia improved women’s mobility by removing restrictions on obtaining a passport and traveling abroad. New legal amendments also equalized a woman’s right to choose where to live and leave the marital home. |

2020 |

|

Parenthood |

Saudi Arabia prohibited the dismissal of pregnant workers. |

2020 |

|

Pension |

Saudi Arabia equalized the age (60 years) at which women and men can retire with full pension benefits. It also mandated a retirement age of 60 years for both women and men. |

2020 |

|

Workplace |

Saudi Arabia prohibited gender discrimination in employment. |

2020 |

|

Workplace |

Saudi Arabia eliminated all restrictions on women's employment. |

2020 |

Source: World Bank report on Women, Business, and the Law 2021.

Details on reforms can also be found here.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.