During the waning days of the Trump administration, 22 Republican Representatives, led by Doug Lamborn of Colorado, sent a letter to the president urging him to erase Palestine refugees and their rights as a matter of U.S. policy.

“The issue of the so-called Palestinian ‘right of return’ of 5.3 million refugees to Israel as part of any ‘peace deal’ is an unrealistic demand, and we do not believe it accurately reflects the number of actual Palestinian refugees,” these members of Congress argued.1

This attempt by members of Congress to minimize the dimension of the Palestine refugee issue and negate refugee rights was not only intended to tip the scales of U.S. policy further in Israel’s favor; it also dovetails with a deliberate Israeli strategy to advance what historian Nur Masalha dubbed “the memoricide of the Nakba,” or “catastrophe” in English — Israel’s large-scale dispossession of two-thirds of Palestine's Arab population in the course of its establishment in 1948, a process of dispossession which many Palestinians rightfully argue continues to this day.

“Zionist methods have not only dispossessed the Palestinians of their own land,” Masalha wrote, but “they have also attempted to deprive Palestinians of their voice and their knowledge of their own history.”2

An estimated 750,000 Palestinians were either driven from their homes or fled during the Nakba. This figure represents approximately 75% of indigenous Palestinians who had previously resided within what became Israel’s armistice lines in 1949. Israel disallowed virtually all Palestinians from returning afterward. It also demolished between 400 and 500 Palestinian cities, towns, and villages during the Nakba in attempt to efface the Palestinian presence from the land.

Without centering the events of the Nakba as the foundational issue of the Palestinian-Israeli impasse, policymakers are led astray into believing that a just and lasting resolution merely requires an end to Israel’s military occupation of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. Such a resolution would negate Palestinian refugee rights to repatriation and restitution of property and would be unjust.

Nakba denial simultaneously serves as a mechanism to bolster Israel’s denial of Palestinian refugee rights, to whitewash Israel’s dispossession of Palestinians, to obfuscate Israel’s eliminationist origins, and to encloak Israel’s establishment in an ahistorical, virtuous narrative. To counter this insidious attempt at Nakba memoricide by U.S. politicians and others, it is instructive to review the

Israel’s first president, Chaim Weizmann, tried to convince James McDonald, the first U.S. ambassador to Israel, that the Palestine refugee crisis represented a “miraculous simplification of Israel’s tasks.”3

However, as the archives make abundantly clear, U.S. diplomats understood that Palestinian flight was not a preternatural phenomenon, as Weizmann claimed. Rather, it resulted from a calculated and deliberate policy of expansionism first by Zionist militias and later by the Israeli military that induced Palestinian dispossession through terrorism and atrocities. Israel’s dispossession of Palestinians was solidified through the systematic looting and destruction of their property, as these diplomats attested, resulting in an extremely grave humanitarian crisis.

Below are five things U.S. diplomats knew and understood about the Nakba as it unfolded from the files of the U.S. Consulate in Jerusalem.

1. Israel would not be contained within the borders of the Jewish State as envisioned in the Partition Plan

There is no evidence in the archives that U.S. diplomats knew about the adoption of Plan Dalet — a blueprint for the conquest and depopulation of large swaths of the country that called for the “destruction of villages” and mandated the “population must be expelled outside the borders of the state”4 — by Zionist leaders in March 1948.

However, despite their lack of precise intelligence, U.S. diplomats nevertheless feared that the Zionist leadership would not be content with the envisioned borders of the Jewish State as delineated in the United Nations Partition Plan.

For example, in

“We believe that Haganah operations will remain defensively offensive until May 15 after which they will go on [an] all out offensive to secure frontiers [for the] new Jewish State and improve lines of communication.” Wasson relayed prevailing opinion that the “Jews will be able [to] sweep all before them unless regular Arab armies come to [the] rescue.”5

Ten days later, on May 13, Wasson warned again that “Speculation is rife as to whether [their] new-found strength may not encourage Jews to attempt to acquire more territory,” citing a Jewish Agency spokesman that “Ben Gurion had always said that [the] main aim of Jews was to get all of Palestine.”6

2. The Palestinian exodus was spurred by Zionist and Israeli atrocities

The archives contain numerous grim, matter-of-fact accounts of massacres of Palestinian civilians by Zionist militias and the Israeli military both before and after the establishment of the State of Israel as a method to accomplish this expansionism.

On January 5, 1948, the Haganah bombed the Semiramis Hotel in Jerusalem, killing more than 20 Palestinian civilians. U.S. Consul General Robert Macatee characterized the bombing as “outstanding even in [the] present state of constant terror in Palestine.” The initial response to the atrocity was that it was “so completely motiveless as to place [it] in [the] category of nihilism.”7

While the Semiramis Hotel bombing prompted grave concerns among Palestinians in Jerusalem about their safety, the notorious massacre of Palestinians by the Irgun and Stern Gang militias three months later in Deir Yassin precipitated widespread panic. Wasson noted that of the initial number of reported victims “half, by their [the Irgun and Stern Gang] own admission to American correspondents, were women and children.”

A visit by consular officers to Hussein Khalidi, secretary of the Arab Higher Executive, two days later “found him still trembling with rage and emotion and referring to [the] attack as [the] ‘worst Nazi tactics’.” Wasson believed that “further attacks [of] this nature can be expected.”8

Although the intensity of fighting prevented U.S. diplomats from venturing far from their posts and providing direct, on-the-ground reporting of the future massacres that Wasson anticipated, indirect reports of further atrocities filtered back to them.

For example, in November, the U.S. Consulate General reported to the State Department about atrocities committed the previous month by Israeli troops as they conquered territory in

At the village of Dawaymeh, near Hebron, in what historian Ilan Pappe describes as “probably the worst in the annals of Nabka atrocities,”9 U.S. diplomat William Burdett wrote that “Arabs claim 500 to 1,000 men, women and children [were] lined up and killed by machine gun fire after [the] village [was] captured” in a “massacre” which was confirmed by U.N. observers who were unable to ascertain the exact number of victims.

Burdett also reported that after Palestinians surrendered in three villages in the Galilee, “Jews ordered [the] villagers [to] turn in all arms within 25 minutes. When [they were] unable [to] meet [the] deadline 5 men from one village and 2 from each of [the] others [were] selected at random and shot.” Burdett concluded rather laconically that “Conduct [of] this nature can only impede [a] final Pal[estine] settlement and leave rankling bitterness.”10

3. Systematic looting and destruction of property was intended to prevent Palestinian refugees from returning

While Israeli atrocities drove Palestinians from their homes, U.S. diplomats also recorded the systematic looting and destruction of Palestinian property that took place by Zionist militias and the Israeli military, and understood that these acts were designed to prevent Palestinian refugees from returning to their homes.

The U.S. Consulate General in Jerusalem took special note of the systematic looting of the Katamon and German Colony neighborhoods in the city. On May 26, a U.S. diplomat visited these areas, “both normally Arab quarters, now in Jewish hands. He found heavy fighting had caused [an] appalling amount [of] destruction [in] Katamon with houses in certain sections completely destroyed principally by explosions. All houses and shops had been broken into and organized groups were still carrying furniture, household effects and supplies from Arab buildings and pumping cistern water into tank trucks. Evidence indicated [a] clearly systematic looting [of the] quarter.”11

Israel’s looting of Palestinian property in Jerusalem extended to the homes of Palestinian-Americans like Issa Saba, who lived in the Upper Bakaa neighborhood, prompting a U.S. investigation. On June 5, a U.S. diplomat discovered his house to be “thoroughly looted with doors broken in and [the] interior in shambles; valuable possessions including rugs [were] removed; wanton destruction included ripping of pictures and smashing [of a] washing machine and frigidaire.” The consulate “will of course continue to press [the] matter vigorously but doubts it will be possible [to] recover [the] stolen articles or that [the] JA [Jewish Agency] will consider any claims for compensation.”12

U.S. diplomats understood that this looting of Palestinian property was not merely avaricious in nature but was also intended to create a situation which would make it difficult, if not impossible, for Palestinian refugees to return to their homes after the fighting.

In areas of Jerusalem occupied by Israeli forces, U.S. Consul General John MacDonald wrote on July 27 that there was “no respect or protection for Arab interests and property. Every Arab house and shop has been thoroughly looted and even window frames, doors, plumbing, electric fixtures and installations [were] removed.”

Those Palestinians who managed to remain in their homes hardly fared better according to MacDonald. “The few Arabs remaining [in] this area are constantly searched by Military authorities who remove furniture, clothing and any money in their possession. If authorities in control disapprove [of] this action as they alledge [sic] they apparently are unable [to] control [the] situation.”

Due to these conditions, “There is little if any possibility of Arabs returning to their homes in Israel or Jewish occupied Palestine,” MacDonald noted.13

4. Palestinians under Israeli control were subjected to harsh, discriminatory treatment

MacDonald’s description of the harsh treatment meted out to Palestinians under Israeli rule in Jerusalem was echoed by similar concerns expressed by the U.S. Consulate in Haifa. In a July 14 report, U.S. diplomat Aubrey Lippincott reported that in Acre, “Of those few hundreds [of Palestinians] who remain, all are women, children and old men. They are fed by daily rations from Haifa which are enough for subsistence but scarcely more. The sisters at the French Convent said their diet was totally lacking in fresh vegetables, fruit and milk products.”

All military-age male Palestinians in Acre were taken as prisoners of war and “were kept at work fourteen hours a day in building fortifications and gun emplacements along the coast.”

Lippincott also raised concerns about discriminatory public health measures in the city. Doctors there blamed a typhoid epidemic “on the Jews’ failure to protect the Arabs’ water supply. Claiming that new cases of typhoid appeared daily, the doctors stated that the Jews had their own purified water but that nothing was done and no facilities were made available to protect Arab water.”14

In addition to Palestinians’ lack of access to adequate food and water, Israel continued to forcibly displace Palestinians under their rule. For example, in Haifa, Lippincott relayed a report from the Spanish consul on July 3 noting that the military commander “ordered all Arabs in Haifa to evacuate their homes,” with Christian and Muslim Palestinians being segregated into different neighborhoods within the city.

Many Palestinians had taken refuge in the Stella Maris Monastery in Haifa. They were ordered “to evacuate within one hour” by the Israeli military commander, who threatened to “use armed force” if his orders were not followed. Palestinians protested to no avail that their forced removal to the neighborhoods of Wadi Nisnas and Wadi Salib would turn those areas into “concentration camps.” Lippincott noted the explicit discriminatory nature of the expulsion orders in Haifa: “The Jewish order applies only to Palestinian Arabs.”15

5. Palestine refugees faced catastrophic losses amid appalling conditions

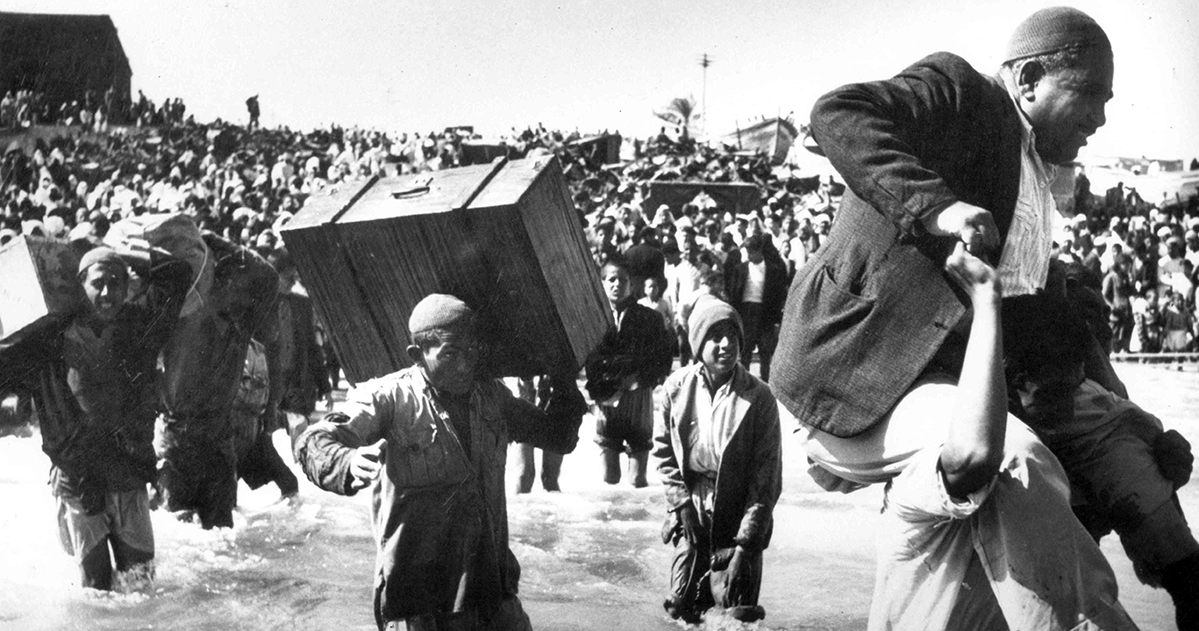

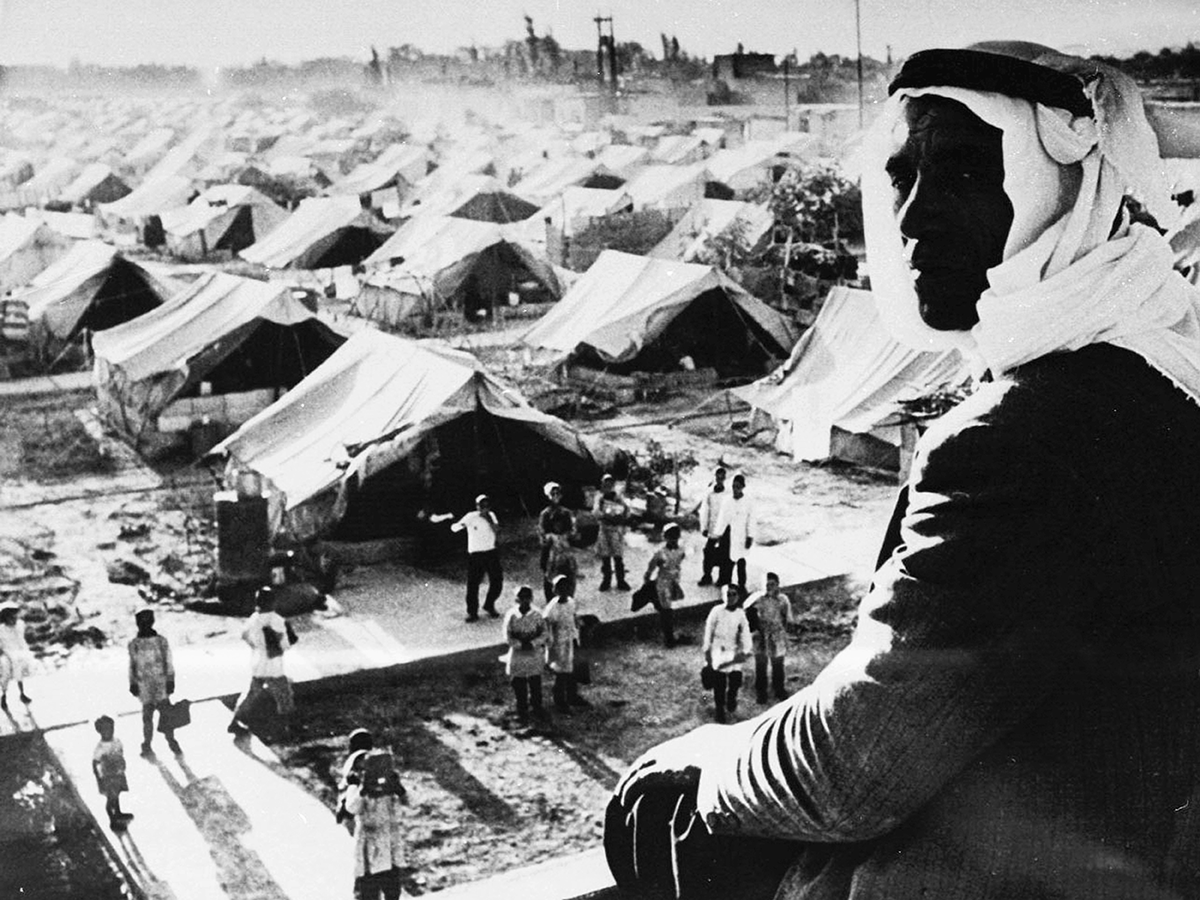

As dire as conditions were for Palestinians remaining under Israeli rule, those expelled or forced to flee from their homes beyond Israeli lines were subjected to extremely brutal conditions, often being forced to sleep outdoors with little or no access to food, water, sanitation, and health care as many urgent reports in the archives attest.

An October 17 telegram from the newly-founded U.S. Embassy to Israel set off alarm bells in the State Department. The “Arab Refugee tragedy is rapidly reaching catastrophic proportions and should be treated as a disaster,” warned Ambassador McDonald, basing his assessments on “15 years of personal contact with refugee problems.”

“Approaching winter with cold heavy rains will, it is estimated, kill more than 100,000 old men, women and children who are shelterless and have little or no food. [The] Situation requires some comprehensive program and immediate action that dramatic and overwhelming calamities as [a] vast folld [sic, flood] or earthquake would invoke. Nothing less will avert horrifying losses.” “Every consideration of mercy, justice and expediency” called for an overhaul of international efforts to prevent a large-scale loss of life, McDonald concluded.16

McDonald’s urgent warning prompted Undersecretary of State Robert Lovett to seek the opinions of other U.S. diplomatic outposts in the regions. They all concurred with McDonald’s assessment of the gravity of the Palestine refugee crisis. “Because of insignificant accomplishments to date [the] magnitude [of the] effort now required [has] greatly increased,” added Burdett from Jerusalem. The “seriousness [of the] refugee problem cannot be overemphasized, herculean and immediate effort [is] required.”17

Chiming in from the U.S. Legation in Damascus, where he witnessed the influx of Palestinian refugees to Syria, U.S. Minister James Keeley offered one of several of his acerbic commentaries on the devastating impact of Israel’s creation for the Palestinian people. The legation “heartily shares McDonalds [sic] estimate of [the] magnitude of [the] Arab refugee tragedy and [the] inadequacy of present and prospective relief and resettlement resources … which unless speedily remidied [sic] will inevitably result in shocking losses among refugees.”

However, rather than viewing the issue solely as a humanitarian one, Keeley insisted on understanding the refugee crisis as an intrinsic part of the political turmoil created by the recommendation of the U.N. to partition Palestine against the wishes of its indigenous majority inhabitants. It would be a “major political error for [the] UN now to endeavor [to] disassociate itself from [the] Pal[estine] refugee problem which is and must remain [an] integral part of [the] whole Pal[estine] complex until peacefully resolved.”

And unlike McDonald, who analogized the refugee crisis to a natural disaster, Keeley insisted on the primacy of human agency in Israel’s dispossession of the Palestinian people. He concluded that “all concerned [must] continue [to] work for [a] just settlement [of the] Pal[estine] problem thus eliminating [the] cause [of the] disaster for which unlike [an] ‘earthquake’ man not god must take blame.”18

U.S. concern for the humanitarian dimensions of the Palestine refugee crisis spurred the Truman administration to support the establishment in November 1948 of a short-term, emergency program, U.N. Relief for Palestine Refugees.19 This agency served as a precursor to the more long-standing U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), which continues to provide social services to Palestinian refugees today.

And in what would undoubtedly be shocking news to Rep. Lamborn and other members of Congress who have tried to erase Palestinian refugees’ rights, the United States also supported their right of return through the passage of U.N. General Assembly Resolution 194, which resolved that Palestinian “refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible.”20

As the refugee crisis persisted into 1949, President Harry S. Truman declared himself to be “rather disgusted” with Israel’s refusal to repatriate Palestinian refugees21 and his appointed delegate to the Palestine Conciliation Commission, Mark Ethridge, concluded that “Israel’s refusal to abide by the GA assembly resolution, providing those refugees who desire to return to their homes, etc., has been the primary factor in the stalemate” in the Palestine refugee crisis. “Aside from her general responsibility for refugees,” Ethridge noted, “she has particular responsibility for those who have been driven out by terrorism, repression and forcible ejection.”22 However, the Truman administration’s commitment to the political rights of Palestinian refugees proved to be short-lived due to a combination of Israeli intransigence and a concomitant U.S. unwillingness to sanction Israel.

Nevertheless, the Palestine refugee crisis remains as central today as it was nearly 75 years ago. With an estimated 7 million refugees, of whom 5.7 million are registered with UNRWA, the needs and rights of Palestinian refugees must be centered in future peacemaking attempts.

In formulating future policy toward Palestine refugees, U.S. policymakers would be well-served to review the archives to gain an appreciation for just how granular of a view the United States had of the Nakba as it unfolded and the moral responsibility the United States bears for its perpetuation today.

Josh Ruebner is a PhD candidate at the University of Exeter’s European Centre for Palestine Studies and is writing a dissertation examining U.S. policy toward Palestinian self-determination between the Wilson and Truman administrations. He is also an Adjunct Lecturer of Justice and Peace Studies at Georgetown University. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

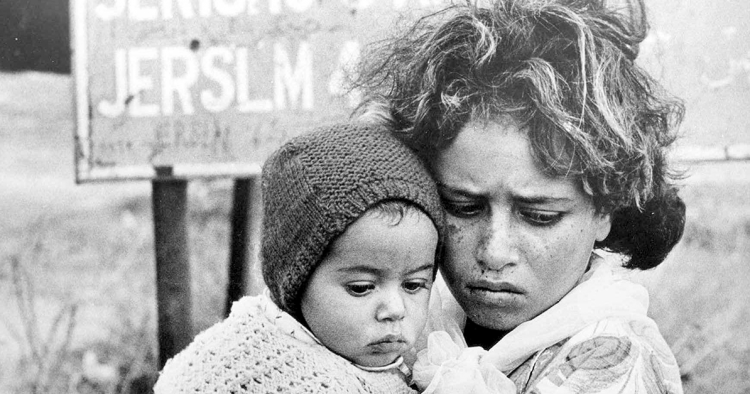

Main photo: Palestinian children driven from their homes by Israeli forces huddle beneath a Jerusalem road sign, 1948. Photo by George Nemeh (CC BY-SA 3.0 License). Pictures From History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Endnotes

- Lamborn, et. al. to President Donald J. Trump, December 11, 2020, available at: https://lamborn.house.gov/sites/lamborn.house.gov/files/Rep.%20Lamborn_UNRWA%20Report%20letter_December%202020.pdf

- Nur Masalha, The Palestine Nakba: Decolonising History, Narrating the Subaltern, Reclaiming Memory, Zed Books, London, United Kingdom, 2012, p. 88, 89.

- James G. McDonald, My Mission in Israel, 1948-1951, Simon and Schuster, New York, New York, 1951, p. 176.

- Walid Khalidi, “Plan Dalet: Master Plan for the Conquest of Palestine,” Journal of Palestine Studies, Volume 18, Number 1 (Autumn 1988), p. 29, available at: https://www.palestine-studies.org/sites/default/files/attachments/jps-articles/Plan%20dalet.pdf

- Cable 530, Wasson to Marshall, May 3, 1948, RG 84, Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Jerusalem Consulate General, 1948, Box 4, 800, Palestine, Folder 3, National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

- Telegram 599, Wasson to Marshall, May 13, 1948, RG 84, Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Jerusalem Consulate General, 1948, Box 4, 800, Palestine, Folder 3, National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

- Telegram 26, Macatee to Marshall, January 7, 1948, RG 84, Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Jerusalem Consulate General, 1948, Box 3, 800, Palestine, Folder 1, National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

- Telegram 431, Wasson to Marshall, April 13, 1948, RG 84, Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Jerusalem Consulate General, 1948, Box 4, 800, Palestine, Folder 2, National Archives, College Park, Maryland, reprinted in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1948, The Near East, South Asia, and Africa, Volume V, Part 2, Document 145, available at: https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1948v05p2/d145

- Ilan Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Oneworld Publications, Oxford, England, 2006, p. 195.

- Telegram 1485, Burdett to Marshall, November 16, 1948, RG 84, Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Jerusalem Consulate General, 1948, Box 4, Palestine, Folder 6, National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

- Telegram 762, Burdett to Marshall, May 27, 1948, RG 84, Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Jerusalem Consulate General, 1948, Box 4, 800, Palestine, Folder 3, National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

- Cable 865, Burdett to Marshall, June 7, 1948, RG 84, Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Jerusalem Consulate General, 1948, Box 1, 310, National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

- Telegram 1126, MacDonald to Marshall, July 27, 1948, RG 84, Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Jerusalem Consulate General, 1948, Box 5, 800, Palestine, Refugees, National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

- Lippincott to Marshall, July 14, 1948, RG 84, Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Jerusalem Consulate General, 1948, Box 3, 800, Palestine, Folder 1, National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

- Telegram 98, Lippincott to State Department, July 3, 1948, RG 84, Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Jerusalem Consulate General, 1948, Box 4, 800, Palestine, Folder 4, National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

- Circular telegram, Lovett, October 18, 1948, RG 84, Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Jerusalem Consulate General, 1948, Box 5, 800, Palestine, Refugees, National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

- Telegram 1410, Burdett to Marshall, October 21, 1948, RG 84, Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Jerusalem Consulate General, 1948, Box 5, 800, Palestine, Refugees, National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

- Telegram 39, Keeley to Jerusalem, October 21,1948, RG 84, Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Jerusalem Consulate General, 1948, Box 5, 800, Palestine, Refugees, National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

- A/RES/212 (III), November 19, 1948, available at: https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-179872/

- A/RES/194 (III), December 11, 1948, available at: https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-177019/

- The President to Mr. Mark F. Ethridge, at Jerusalem, April 29, 1949, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1949, The Near East, South Asia, and Africa, Volume VI, Document 617, available at: https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1949v06/d617

- The Ambassador in France ( Bruce ) to the Secretary of State, June 12, 1949, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1949, The Near East, South Asia, and Africa, Volume VI, Document 753, available at: https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1949v06/d753

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.