Summary

ISIS began waging an effective and deadly insurgency in central Syria immediately after the Syrian regime and its allies captured the area in late 2017. ISIS’ operations first targeted urban centers along the western Euphrates before shifting focus in spring 2018 to the transport lines and mountains running along the M20 from Khunayfis to Shoula. These operations have reached as far west as Khunayfis — just 40 miles from Damascus Governorate — as far north as Rahjan, Hama — just 15 miles from Idlib Governorate — and span the length of the Euphrates from Boukamal in the south to Ruseifa in the north. In the past week alone ISIS launched two simultaneous attacks in Homs, followed by a third attack in north Hama the next day. The insurgency has killed a minimum of 860 pro-regime fighters, with the true number of deaths likely being twice that. From brigadiers and ex-rebels to Republican Guard and local militias, every type of unit and soldier has been targeted by these sophisticated attacks.

Methodology

Unlike most research on ISIS this report almost entirely ignores the group’s local propaganda, relying instead on reporting from its opponents, the Syrian regime forces. Self-reported regime losses in the region were collected from Nov. 10, 2017 through March 31, 2020. These “martyrs” are reported on loyalist Facebook pages, community pages, and unit pages. In general, most martyrdom posts include the location of death — with varying degrees of specificity — although during this period there were an additional 160 martyrs reported with no location given.

The larger limitation with this method, however, is the lack of reporting from central Syria. Many deaths go unreported, sometimes because the bodies cannot be recovered or the men are assumed missing — all too common a situation in the remote mountains and empty desert that make up the Badia region. Compounding this is the fact that the deaths of reconciled rebels are almost wholly unreported. Martyrdom reporting is a communal activity, relying on family, friends, or community leaders to publicize the death of a local. Rebels who have reconciled and joined the ranks of regime forces rarely receive such honors, and if they do, news of their deaths is rarely shared outside their community. This second factor makes it particularly difficult to find out about such deaths due to the impossibility of searching every Facebook page for every Syrian community. Outside of ex-rebels, the deaths of poor and single loyalist martyrs often go unreported as there is no one in their hometowns with the means to share the news.

All this is to say that the numbers of men killed and trends over time presented here are not exact, but meant to provide a baseline for the deaths inflicted by the insurgency. Extensive interviews were conducted with members of the National Defense Forces (NDF) stationed in Palmyra and Uqayribat in order to support the analysis of this data.

"This new operation [in Jabal Bishri] appears to mark the first time Russian forces have taken an offensive role in the region since 2017, more than two years after Russian President Vladimir Putin announced his own victory over ISIS."

Introduction

More than 40 men died in the three-week battle to capture Uqayribat from ISIS in late August, 2017. The town had been a stronghold of the terrorist group, with the vast majority of its male population fighting in its ranks. Now it is nearly empty, still largely in ruins, reduced once more to an unimportant backwater town in the years following the expulsion of ISIS. But in early 2020 Uqayribat once again became a frontline town. “There is some worry that ISIS will use the M45 to attack Hama, or rather we know that they are planning that,” Mohammad, a member of the NDF recently deployed to Uqayribat, told the author in March. “From here to Palmyra, there is very little population but ISIS activity.”

This most recent deployment is just the next step in the cat and mouse game between the regime and ISIS cells. “We have this info about a serious attack though, so preparations are being made,” continued Mohammad. “Often they cancel the plans if there is some show of force.” This has been the crux of the regime’s anti-ISIS operations: shifting forces around hoping to scare off any major attack. More often than not this simply results in the ambush of regime patrols, but recently some “progress” has been made. In February, Russian forces joined Syrian Arab Army (SAA) units in a concerted push to reclaim Jabal Bishri, the mountain range between Sukhnah and Deir Ez Zor that had been under ISIS control since April 2019. This push coincided with an NDF advance in southeast Raqqa, “clearing” tens of kilometers of land around the town of Ruseifa.

While appearing on the surface to be major successes, both of these operations made little actual progress. Few ISIS fighters or equipment were killed or captured in either advance, and according to Mohammad, “ISIS have partially relocated or rather spread their best forces after the full takeover of Jabal Bishri. Now there are just some cells in this area.”

Indeed, regime forces had to wait only one month to see the failure of their operations. After a lull in attacks during the second half of March, ISIS has erupted across central Syria in the first 10 days of April. Attacks have occurred in southwest Deir Ez Zor, on the highway between Shoula and Ruseifa, and on Jabal Bishri itself. Meanwhile, on April 9 ISIS conducted two simultaneous attacks that carried on into April 10 — one just south of Sukhnah and the second around Wadi Waer, near the Iraqi border. On April 10, ISIS launched the attack Mohammad and his men had been waiting for — except instead of striking along the now reinforced M45, ISIS militants managed to move along the M42, past the large town of Ithriya, and attacked the town of Rahjan in northern Hama near the Idlib border.

A notable development prior to this most recent ISIS surge was the involvement of the Russian military in “clearing” Jabal Bishri. Prior to the Jabal Bishri operation, Russian military units were concentrated in Palmyra, helping ensure the town was protected from any potential ISIS attack, and only used their air force on the rare occasion when they directly engaged ISIS. This new operation appears to mark the first time Russian forces have taken an offensive role in the region since 2017, more than two years after Russian President Vladimir Putin announced his own victory over ISIS, stating “if the terrorists raise their heads again, we will strike them with a force they haven’t seen before.”1 And yet, since those strong words ISIS has killed over 800 loyalist fighters in hundreds of brazen attacks and infiltrated dozens of miles behind regime lines.

"On Sept. 28, 2017, ISIS launched a major counter-offensive, the first sign that territorial loss in no way meant the defeat of the group. While lasting only three weeks, ... [it] briefly succeeded in capturing or besieging every settlement between Palmyra and Deir Ez Zor."

Damascus Reclaims the Badia

On May 23, 2017, the Syrian regime concluded its operation in the eastern Damascus countryside and launched a major offensive against ISIS in central Syria. The aim was eventually to lift the siege of Deir Ez Zor, where regime forces had fended off ISIS attacks since July 2014. On May 31, 2017 a concurrent operation was launched in east Hama in support of the central Syria advances. These two offensives ended on Sept. 27 and Oct. 3, respectively, with over 1,000 reported pro-regime deaths. Palmyra, Arak, Sukhna, and Deir Ez Zor cities had been freed from ISIS, and the western Euphrates from Deir Ez Zor to Raqqa was under Damascus’ control.

But on Sept. 28, 2017, ISIS launched a major counter-offensive, the first sign that territorial loss in no way meant the defeat of the group. While lasting only three weeks, the al-Adnani Offensive, as ISIS named it, briefly succeeded in capturing or besieging every settlement between Palmyra and Deir Ez Zor, as well as capturing the town of Qaryatayn, near the border of Damascus Governorate. At least 300 loyalist fighters were reported killed in the offensive and regime counter.

Following this, Damascus renewed its anti-ISIS operations, seizing the large town of Mayadeen on Oct. 17 — losing at least 79 fighters in the process — and finally capturing Boukamal, the last major ISIS stronghold west of the Euphrates, on Nov. 9, 2017. In its announcement of victory in Boukamal, the Syrian Army General Command hailed “the fall of the ISIS terrorist organization project in the region.”2

“In its announcement of victory in Boukamal, the Syrian Army General Command hailed ‘the fall of the ISIS terrorist organization project in the region.’”

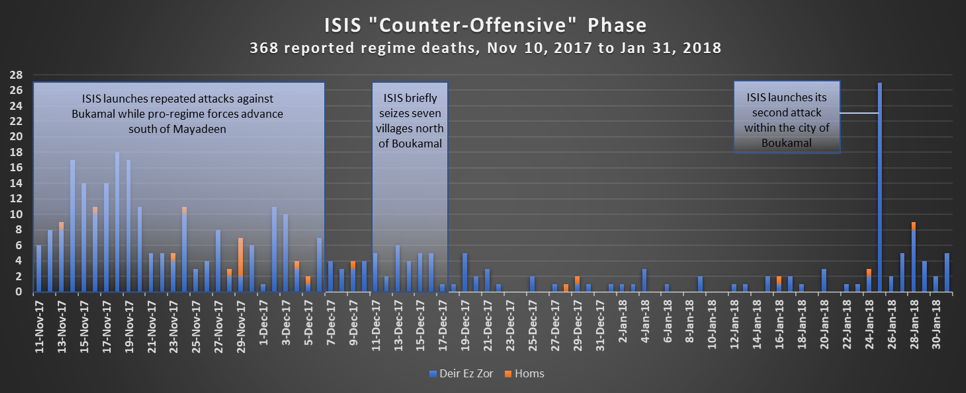

ISIS “Counter-Offensive” Phase: Nov. 10, 2017 to Jan. 31, 2018

For the first three months following Damascus’ victory announcement, ISIS largely focused its campaign on the string of towns stretching from Boukamal to Mayadeen. This phase of the insurgency involved massive, sustained attacks on urban centers. At several points ISIS won back some villages, although territorial gains were inevitably reversed. It is entirely possible that in this period ISIS hoped to actually regain territory, not just carry out more classic insurgent attacks.

The first urban push came the day after Damascus announced its victory over the group. On Nov. 10, 2017, ISIS forces re-entered Boukamal, taking back nearly half of the city.3 Boukamal would change hands several times over the next month, as regime and allied forces slowly advanced south from Mayadeen capturing the string of villages still held by ISIS. On Dec. 6, ISIS was finally pushed out of all urban centers on the western bank of the Euphrates.4 At least 233 pro-regime Syrian and foreign fighters died in Deir Ez Zor during this period, while ISIS carried out only three attacks in Homs. The first killed two Syrian Hezbollah fighters in Humaymah on Nov. 23, the second was a carbomb attack on Sukhnah on Nov. 28, and the third was an IED attack that killed six men on Nov. 29. ISIS also conducted a multiple suicide bombing attack on the Deir Ez Zor Military Airport on Nov. 13, destroying Syrian Air Force planes.5

Just one week after losing all of its territory, ISIS launched another attack north of Boukamal. On Dec. 11, 2017, it seized Hasrat, followed by six more villages in the area the next day, killing at least 41 pro-regime fighters before eventually being forced out by Dec. 17.6 The rest of December saw ISIS attacks around Mayadeen and Boukamal, but with a noticeable decrease in both effectiveness and intensity, and still limited attacks in Homs.

ISIS made its final urban push on Jan. 25, 2018, when it again entered the outskirts of Boukamal.7 Unlike earlier fighting around the city, this attack was accompanied by a plethora of ISIS photo and video reports, indicating a concerted effort by the group to project a strong image to its global supporters. The attack ultimately resulted in no territorial changes and marked the beginning of reduced ISIS activity in the area. Conversely, while ISIS attacks in Homs during January were just as rare as during the previous two months, this would soon change.

"For the first three months following Damascus’ victory announcement, ISIS largely focused its campaign on the string of towns stretching from Boukamal to Mayadeen."

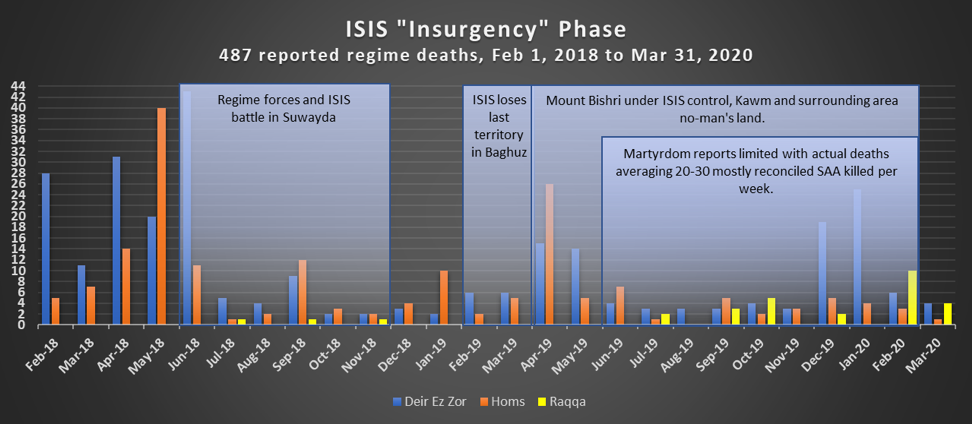

ISIS “Insurgency” Phase: Feb. 1, 2018 to Present

The past 26 months of ISIS’ insurgency in central Syria should be viewed as a both a time of geographic centralization and the complete destruction of geographic barriers for the group. From February 2018 through June 2018 ISIS appears to have shifted its operations further and further west, settling on the eastern half of Homs Province, where it attacked regime forces from Palmyra to Sukhnah to Humaymah. This is the geographic centralization of the insurgency.

However, the group also maintained a steady pace of operations in Deir Ez Zor at this time, and from June to December 2018 fought a brutal battle against regime forces in northeast Suwayda Province, the southwest corner of what is considered the Badia. Since then, attacks have reached all the way into eastern Hama, eastern Raqqa, and central Homs. Thus, despite centralizing its operations in Homs, ISIS has proven since the beginning of its insurgency that it is not confined by any geographic bounds.

The exact locations of some of these attacks can be identified, either through ISIS or loyalist claims or by geolocating ISIS propaganda. Attacks during this phase of the insurgency have been mapped in the link below and color coded by three-month periods. What should be immediately clear is how widespread attacks are even within these short time frames, indicating that either ISIS operates separate cells in each of the regions or that individual ISIS cells have the ability to traverse this area in short of periods of time.

If you're unable to view the embedded map, click here for a screenshot.

According to Syrian Intelligence, the ISIS cells in central Syria are commanded by an former mid-level SAA officer from Jobar, Damascus who deserted in 2013. This man — whose real name is unknown but goes by the aliases Abu Abdallah, Sheikh Qaduli, Soleiman Rahman, and Dr. Rahman Zaid al-Shami — first joined the jihadist Green Battalion, formed by Saudi foreign fighters, before joining ISIS in 2014. He is believed to have been in Idlib City during the fall of Baghouz, based on intercepted communications between him and fighters in Baghouz.

are counted as Homs Governorate.

During this 790-day period, loyalist Facebook pages reported deaths from ISIS attacks in central Syria on at least 253 days. While some of these deaths may have actually occurred on the same day and simply been reported later, this still gives a rough idea of the frequency of ISIS activity in the region.

The author recorded 487 reported deaths, but interviews with a Palmyra NDF fighter confirm that this number is far too low. According to the soldier, deployed to Palmyra at the time, small groups of mostly reconciled rebels were being sent out on near daily patrols: “These guys get sent out in the desert with little support and they seldom return, and if they return, they get sent out again. This tactic seems to get rid of many of these reconciled rebels in this area.” According to him, on average 20 to 30 regime soldiers were being killed per week in Homs, up to 50 per week if Deir Ez Zor is included. Assuming these claims are even close to accurate, the actual number of men killed in this period is at least double what has been recorded. Many were killed when patrols and convoys were ambushed, but others died in large-scale, complex ISIS attacks. These major ISIS attacks and other important events are listed below.

May 20, 2018: ISIS surrenders in the Yarmouk and Tadamoun neighborhoods of south Damascus, accepting an evacuation deal for its fighters. Six buses bring ISIS militants out of Damascus and release them in the Badia near the Suwayda border.8

May 22, 2018: ISIS ambushed a group of 18th Division soldiers 35 km east Uwayrid Dam, killing at least 25 and wounding 14.

June 7, 2018: Regime forces launch an offensive against the ISIS fighters who had been bussed to Suwayda two weeks prior. Fighting between regime forces and ISIS would escalate here over the next six months, possibly explaining the dip in ISIS attacks in central Syria.

June 3-12, 2018: ISIS attacks around Boukamal pick up beginning on June 3 and peak on June 8, when the group launches a broader attack on the city. ISIS withdraws on June 12 after killing at least 38 pro-regime Syrian and foreign fighters.9

July 25, 2018: ISIS militants equipped with suicide belts infiltrate the capital of Suwayda Governorate and several nearby villages, massacring at least 215 people, more than half of whom are civilians.10 This brutal, brazen attack illustrates the group’s ability to still conduct large, coordinated operations and its skill in infiltrating supposedly stable frontlines.

July 31, 2018: ISIS surrenders its last holdings in the Yarmouk Basin of Dara’a and accepts an evacuation deal that again finds militants being bussed to the Badia.11

Aug. 6 to Nov. 19, 2018: The regime launches its final major anti-ISIS offensive, this time targeting the group in the Safa Volcano region of northeast Suwayda.12 This area is connected to the southwestern edge of the Badia, and ISIS likely diverted resources and manpower it otherwise would have used in insurgent attacks to this fight.

Sept. 11, 2018: ISIS ambushes a group of 11th Division, 67th Brigade soldiers near Rashawani, southeast of Sukhnah, killing seven of them. The execution of three of the men, including a colonel, is shown in an ISIS Homs video released in March 2020.

April 11 to April 13, 2019: At least 11 Liwa al-Quds fighters are reported killed fighting ISIS around Bir Ali, near Mayadeen in Deir Ez Zor in the largest reported attack in the governorate since June 2018.

April 18, 2019: Col. Nader Saqr of the 14th Special Forces Division goes missing along with 13 of his men near Bir Didi, east of al-Kawm on the southern edge of Jabal Bishri. Col. Saqr had been the commander of the “Taybah region,” an area stretching from north of Sukhnah to al-Kawm. Rescue parties are sent out but subsequently ambushed and besieged by ISIS. The soldiers hold out for two days before reinforcements arrive and free them. Col. Saqr and his men are never found and are presumed dead. This is the first major attack in Sukhnah-Kawm, and precipitates a serious escalation in the area.13

April 26, 2019: Following the battles on April 18-20, SAA high command meets in Palmyra to discuss launching a possible anti-ISIS operation in Jabal Bishri. By this point it is clear that ISIS controls the mountain, while the villages around the al-Kawm oasis and north Sukhnah area are a no-man’s land. Ultimately, the SAA high command decides against any large operation, citing the lack of air support, as Syria’s limited airframes were reserved for fighting around Idlib.14

May 31, 2019: Eight soldiers from the 17th Division’s 484th Battalion are killed near al-Fayda, Deir Ez Zor, approximately halfway between Shoula and Sukhnah. ISIS attacked a Republican Guard unit in this same location exactly one year prior.

June 12, 2019: ISIS kills at least one 11th Division reserve soldier in Nayriyah, near where the group executed the 11th Division colonel and his men nine months prior.

Sept. 20 to Oct. 9, 2019: Three members of the Border Guard are killed and three others wounded in a village near Ruseifa, Raqqa on Sept. 20. On Oct. 9, ISIS releases a photoset of fighting inside what appears to be an empty village, which they later claim is in the Ruseifa countryside.15 It is unclear if the photoset shows the same attack that occurred on Sept. 20 or a different one. Either way, these incidents make clear ISIS’ expanding area of operations. With control over Jabal Bishri, ISIS is now able to begin regularly striking the Ruseifa area.

Nov. 17, 2019: ISIS releases a photoset of a small unit attacking a village from the nearby mountains.16 These photos were later geolocated near Jubb al-Awar, eastern Hama. This is the first confirmed ISIS attack in the Hama countryside since the group was expelled from the region in late 2017.

Dec. 24 to Dec. 25, 2019: At least 15 fighters from Liwa al-Quds, the SAA’s 17th Division, and the Republican Guard’s 800th Battalion are reported killed in clashes with ISIS in Deir Ez Zor. It is unclear if these are three separate attacks, but at least one occurred near Boukamal.

Jan. 14, 2020: ISIS ambushes several Republican Guard 104th Brigade units near Mayadeen, killing at least 16 fighters, including a brigadier general, over the course of several battles. According to loyalist reports, ISIS militants conducted a “pincer move” to trap the first Republican Guard units and then ambushed the reinforcements.

Feb. 27, 2020: ISIS militants kill a lieutenant and eight of his men from the 14th Special Forces Division’s 554th Regiment in an ambush near Ruseifa, in what is the deadliest reported attack in the governorate yet.

“Despite centralizing its operations in Homs, ISIS has proven since the beginning of its insurgency that it is not confined by any geographic bounds.”

ISIS’ Targets

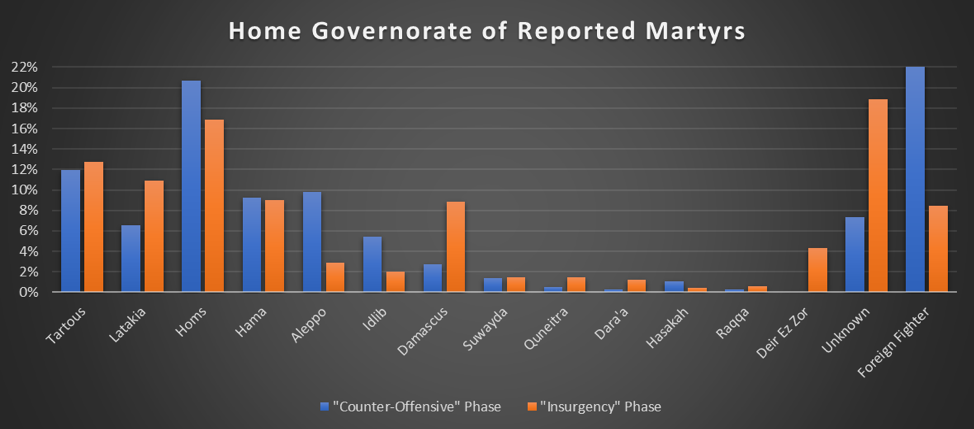

While the regime units that have faced off against ISIS this past year are often described as reconciled rebels, few of the reported martyrs have come from this background. This does not mean that that ex-rebels are not dying by the hundreds in the Badia; rather, it should demonstrate the gaps in the martyrdom data presented in this report.

In fact, as the graph above shows, during both phases just under half of the reported pro-regime martyrs came from the core loyalist communities in Tartous, Latakia, Homs, and Hama. Many of these men hail from the Alawite and Ismaili towns concentrated in these governorates. In the ISIS “Insurgency” Phase there is a significant spike in the number of Damascus-born martyrs, most of whom come from ex-opposition towns. Also important to note is the drop in foreign fighter representation, largely a result of the fact that most foreign fighter units served an offensive role and thus were not as active during 2018 and 2019.

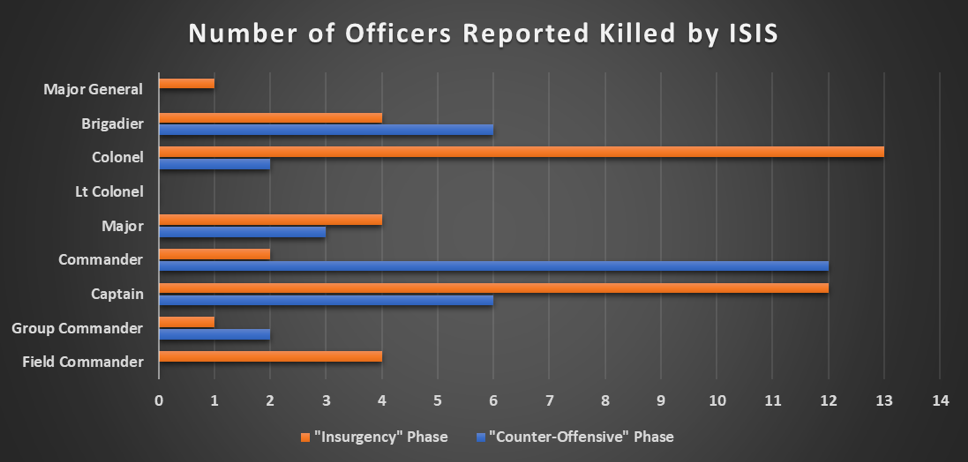

ISIS has not just killed rank-and-file soldiers during its insurgency either. At least 72 officers of the rank of captain or above were reported killed across the two periods, with a significantly higher number of colonels, brigadiers, and major generals killed during the “Insurgency” Phase. Among the officers killed was the commander of the 17th Division’s engineering units, the overall commander of the 11th Division, the commander of the Palmyra-Badia region, the commander of the 18th Division’s engineering units, and the commander of the Taybah Region.

Lastly, over two dozen distinct units have incurred combat losses to this insurgency, ranging from militias to SAA units to the Republican Guard. Among units permanently or rotationally stationed in central Syria, the Republican Guard’s 103rd Brigade, 104th Brigade, and 800th Battalion and the SAA’s 5th Corps, 1st Division, 7th Division, 10th Division, 11th Division, 17th Division, 18th Division, and 14th Special Forces Division have all suffered repeated losses. Among pro-regime militias, Syrian Hezbollah suffered significant losses from late 2017 through mid-2018 while the NDF and the Palestinian Liwa al-Quds are regularly attacked when patrolling the region. Other militias have rotated through for small periods of time, such as elements of the Local Defense Forces from Aleppo, Quwat Di’r al-Watan from Homs, and the Qalamoun Shield Forces and Quwat Hasan al-Watan from Damascus.

“Over two dozen distinct units have incurred combat losses to this insurgency, ranging from militias to SAA units to the Republican Guard.”

Looking Forward

Although it is an overused phrase, ISIS clearly never went away. The organization adapted quickly to its loss of territory and after several months of costly battles targeting urban centers in southern Deir Ez Zor, it efficiently shifted to more classic insurgent attacks striking the entirety of the Badia. ISIS has successfully employed IEDs (including suicide vehicle-borne IEDs) and anti-tank guided missiles, and even continued its use of DIY drone bombs to strike regime-controlled gas and oil infrastructure. These attacks have only grown in strength over time, with the widest geographical reach of attacks occurring over the past year. Despite the regime’s reclamation of Jabal Bishri, ISIS remains unhindered.

Crucial for both ISIS’s freedom to operate and Damascus’ inability to properly counter this insurgency is the reportedly high degree of local support for ISIS and the porous border with Iraq, through which more manpower is able to enter Syria. This second point is particularly important because the SAA currently regards the region from southeast Sukhnah to the Iraqi border as no-man’s land. If Damascus is serious about stopping ISIS attacks, it must secure this area, but without also losing control of the Jabal Bishri and north Sukhnah region. Judging by the regime’s actions over the past two years, there is little chance that it can do so.

About the author

Gregory Waters is a research analyst at the Counter Extremism Project where his work focuses on Syrian and Iraqi armed groups. He received his M.A. in Global Studies and his B.A. with Honors in Political Economy and Foreign Policy in the Middle East from the University of California, Berkeley. He has previously been published by the Middle East Institute, the Atlantic Council, Bellingcat, and openDemocracy, and currently writes about Syria for the International Review.

Endnotes

- Andrew Roth, “On visit to Syria, Putin lauds victory over ISIS and announces withdrawals,” The Washington Post, December 11, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/video/world/putin-russian-forces-will-start-withdrawing-from-syria/2017/12/11/9d9e6bdc-de72-11e7-b2e9-8c636f076c76_video.html.

- “Al-Boukamal city declared fully liberated,” Syrian Arab News Agency, November 9, 2017, https://sana.sy/en/?p=117602.

- “IS jihadists retake nearly half of Syria border town: monitor,” France 24, October 11, 2017, https://www.france24.com/en/20171110-jihadists-retake-nearly-half-syria-border-town-monitor.

- “Syria army clears last IS pockets west of Euphrates: monitor,” France 24, December 7, 2017, https://www.france24.com/en/20171207-syria-army-clears-last-pockets-west-euphrates-monitor.

- Qalaat al-Mudiq, Twitter Post, November 30, 2017, 5:04pm, https://twitter.com/QalaatAlMudiq/status/936355404442939393.

- GregoryPWaters, Twitter Post, December 11, 2017, 3:43pm, https://twitter.com/GregoryPWaters/status/940321196503130114.

- Robert Postings, Twitter Post, January 25, 2018, 7:14am, https://twitter.com/RobertPostings/status/956500602346905605.

- “ISIS Militants Evacuated from Southern Damascus to Desert,” Asharq al-Awsat, May 21, 2018, https://aawsat.com/english/home/article/1275206/isis-militants-evacuated-southern-damascus-desert.

- Talal Kharrat, “ISIS Advancing Against Syrian Regime In Deir Ezzor,” Qasioun News, June 4, 2018, https://www.qasioun-news.com/en/news/show/148729/ISIS_Advancing_Against_Syrian_Regime_In_Deir_Ezzor; “ISIS withdraws from al-Boukamal after days of deadly clashes,” Rudaw, June 12, 2018, https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/syria/12062018.

- “Islamic State kills 215 in southwest Syria attacks: local official,” Reuters, July 25, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-attack/deadly-attacks-hit-syrian-villages-city-of-sweida-idUSKBN1KF0DG.

- Jennifer Cafarella with Brandon Wallace and Jason Zhou, ISIS’s Second Comeback: Assessing The Next ISIS Insurgency, Institute for the Study of War, June 2019, p43, http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/ISW%20Report%20-%20ISIS%27s%20Second%20Comeback%20-%20June%202019.pdf; “In exchange for the release of al-Suwaidaa abductees, Yarmouk Basin is undergoing negotiations between the regime and ISIS to move the last 100 remaining members of Jaysh Khaled and about the “presumed 150 captive” towards the desert,” Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, July 31, 2018, http://www.syriahr.com/en/?p=99223.

- “After the deal of handing over the kidnapped people, hundreds of ISIS members vanish from Tlul al-Safa after 116 days of the deadliest attack ever in al-Suwaidaa,” Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, November 17, 2018, http://www.syriahr.com/en/?p=99223.

- “Syria war: IS 'kills 35' government troops in desert attacks,” BBC, April 20, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-47998354; See also these Facebook posts on the attack: https://justpaste.it/3ex7s, https://justpaste.it/51dqb.

- GregoryPWaters, Twitter Post, April 30, 2019, 12:55pm, https://twitter.com/GregoryPWaters/status/1123269710496157701; Gregory Waters, Twitter Post, April 30, 2019, 2:00pm, https://twitter.com/GregoryPWaters/status/1123286106693234688.

- Calibre Obscura, Twitter Post, October 9, 2019, 2:59pm, https://twitter.com/CalibreObscura/status/1182007577795874822; The video of this attack is published as part of the March 2020 Homs release, and here it is cited as occurring in a village near Ruseifa, Raqqa.

- Calibre Obscura, Twitter Post, November 17, 2019, 8:01am, https://twitter.com/CalibreObscura/status/1196050637294907392; Obretix, April 3, 2020, 6:09pmm https://twitter.com/obretix/status/1246198218762960896.