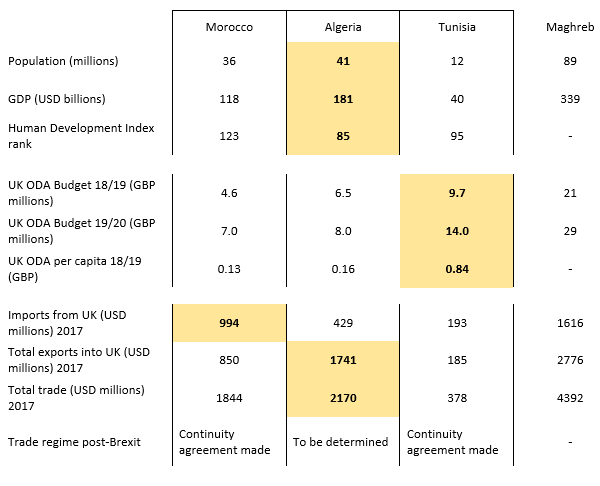

British interests in the Maghreb should not be taken lightly. In 2017, trade between the UK and the Maghreb — the region of North Africa comprising Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia — amounted to over $4.3 billion, while British official development assistance (ODA) in the region exceeded £20 million.

On both the economic and diplomatic fronts, the UK’s relations with the Maghreb have benefited from the EU’s active policy toward the region in the last 25 years. With the making of Association Agreements with the three countries, and through hundreds of millions of euros in ODA since the Barcelona Declaration in 1995, the EU has helped facilitate the Maghreb’s economic integration with Europe, lowering trade barriers and promoting market reform.

The UK’s impending exit from the EU will present a new chapter for British interests in and posture toward the region. If the UK is to find a trade-off for loss of diplomatic and economic heft, it will need to re-prioritize its engagement efforts. Policy continuity toward Morocco and Tunisia appears inevitable; Algeria, in contrast, promises great opportunity for an evolving relationship.

The shape of the UK’s interests in the Maghreb

The UK’s current posture toward the Maghreb is shaped largely by an interest in its stability. Britain’s strategic logic holds that the best preventative treatment for terrorism, irregular migration, disruption to trade, and other perceived threats is economic development alongside evolutionary democratization.

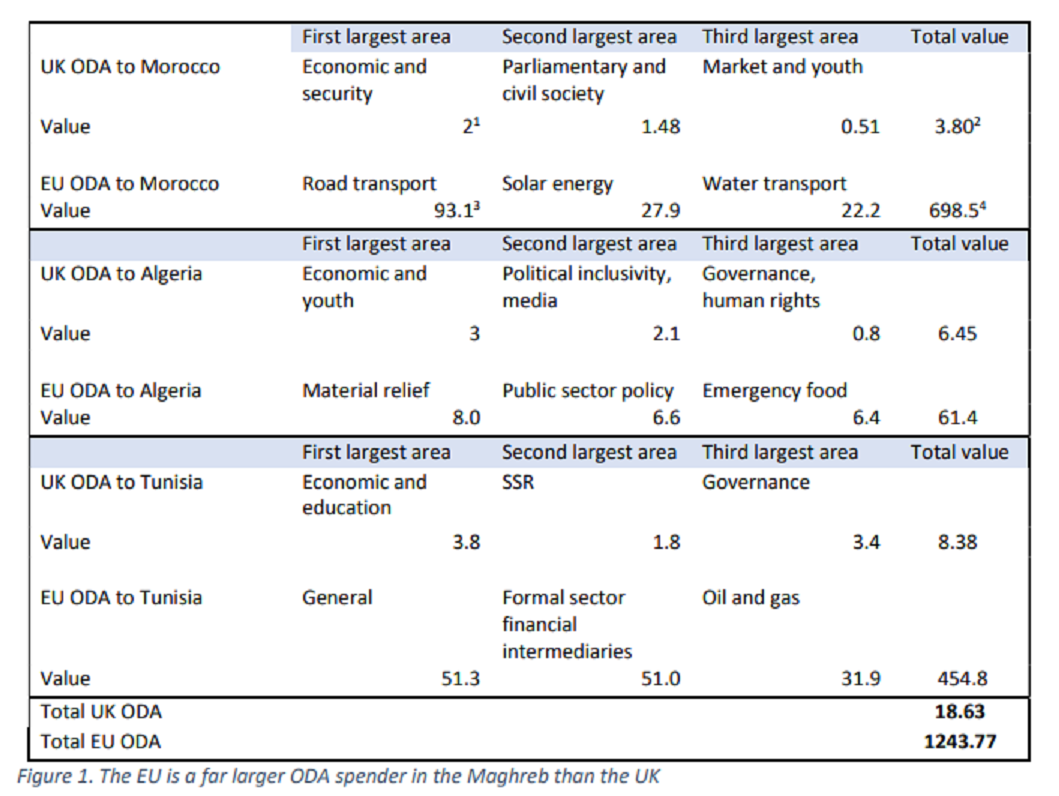

Within this approach, British ODA supports economic diversification, education, political inclusion, and democratization projects. Seeing the vulnerability engendered by poorly diversified economies, the UK tries to encourage a wider range of industries and more balanced markets. Morocco and Tunisia have in the past suffered from global shocks, which were felt by a large proportion of the population. Algeria’s considerable oil and gas resources have provided a greater cushion of foreign exchange reserves ($178 billion in 2014, though down to $88 billion in 2018), which have been used to relieve popular pressure in times of stress. However, this method tends to delay rather than resolve structural issues, leaving the country’s long-term stability at risk.

In addition to these upstream interventions, the UK acts more directly through security assistance or security sector reform projects, such as its considerable support to the Tunisian security sector after the Tunis and Sousse attacks of 2015, or its assistance to Morocco on penal reform. According to the UK’s national security strategy, North Africa is a particular area of concern when it comes to radicalization and terrorism. In 2013, after the attack on the In Amenas facility in Algeria where seven Britons died, the UK announced direct security cooperation with the Algerian government. It is difficult to know the extent to which this continues to function.

In overall trade terms, British interests in the Maghreb are in fact relatively modest. Numbers in the billions are always eye-catching, but in 2017 UK trade with the Maghreb accounted for less than 0.5 percent of total British global imports and exports. British companies in the Maghreb face notable challenges to doing business, in particular protectionist trade regimes and market regulation, including 51:49 local ownership rules. However, the UK is seeking to advance market liberalization and trade integration with the region

UK trade with the Maghreb does include a strategic commodity in significant quantities: hydrocarbons. Algeria is the UK’s fourth-largest hydrocarbons supplier, and the country is a source that the UK has a clear interest in maintaining. While far from being the sole concern, oil and gas tie neatly together British interests in Algeria. The UK has an interest in Algeria liberalizing its hydrocarbons sector to facilitate further British investment, to ensure that production suffices both for export to the UK and for growing domestic demand, and so that the hydrocarbons-dependent Algerian economy does not depress and unleash destabilizing forces.

Meanwhile, British development projects aim to promote diversification of the Algerian economy, such as by backing entrepreneurs through a partnership with MEDAFCO,1 and by supporting World Bank programs both to improve the investment climate by developing institutional capacity and through reforms to strengthen the private sector.2

In pursuing its interests, the UK’s engagement in the Maghreb is uneven. With respect to ODA, the UK spends far more on Tunisia per capita than on Morocco or Algeria. As the most promising of the Arab Spring countries, Tunisia has attracted large amounts of funding from European donors and secured willing partners. Conversely, in Algeria the UK has found it more difficult to collaborate with local partners. In terms of trade, Algeria is the only country in the region with which the UK is running a trade deficit, on account of its large quantity of hydrocarbons imports. British exports to Algeria are relatively meagre compared to the size of the Algerian economy, and compare unfavorably to UK exports to Morocco and Tunisia relative to the size of their economies.

European harmony in the Maghreb?

The UK’s interests in the Maghreb will not change significantly with Brexit and are more or less aligned with those of the EU, with some difference in emphasis. Stability through human development in the Maghreb is a high priority for the EU, even if member states’ exposure to the consequences of instability differ. Compared to the continental member states, the UK has been geographically insulated from irregular migration flows from North Africa, and is more concerned with the incubation of international violent extremism. In addition, the member states on the Mediterranean — especially Spain, Italy, and France — are more integrated economically and socially (home to large diaspora populations) with the Maghreb, which brings another layer of exposure to any destabilization in the region.

However, on the whole, the UK shares the EU’s interests in the Maghreb’s stability, a fact that can be seen through a common development approach. Similar to the UK, EU development logic pursues stability through economic development, market liberalization, integration, democratization, and improved social justice. Where EU development programming tends to differ from British programming is in scale (by around 60 times for the region), and as a consequence by type. The EU can work on large infrastructure projects, while the UK generally seeks more concise capacity-building-style projects (see below).

Leaving the EU will have mixed consequences. British trade with the region has significantly benefited from EU-piloted integration efforts that gave rise to the Association Agreements. These agreements set the basis for the continuity agreements that the UK has already made with Tunisia and Morocco. In this way, British trade with these two countries will continue to benefit from the EU’s earlier investments, but only for as long as the continuity agreements keep up with improvements to the Association Agreements.

Relations with Algeria, however, remain a challenge. Circumspect of international liberalization drives, Algeria is not an easy trade agreement prospect. It has been in accession negotiations with the World Trade Organization since 1987. Hydrocarbons wealth has allowed the country to limit the privatization and opening of the economy to outside interests to a much larger degree than its neighbors. Despite being compelled by the conditions of civil war in the 1990s to seek outside financial assistance, the state managed to reinforce rather than reorient the country’s political economy. But in the 2000s under former President Abdelaziz Bouteflika Algeria did become more outward looking, increasing imports and reducing customs barriers.

Therefore, while the UK’s overall interests in the region will not shift drastically after Brexit, what will mark a significant change is that the UK will no longer be part of the Maghreb’s (and indeed the world’s) largest international development partner. And although the EU will continue to pursue those mutual interests with no cost to the UK, the country will no longer have power to shape EU priorities and programming, nor will it benefit from the diplomatic weight that the international development partnership extends.

A way forward for the UK

Beyond the loss of influence on European policy in the Maghreb, and with the continuation agreements already made, Brexit may not significantly affect UK relations with Tunisia and Morocco for the foreseeable future. However, while Morocco and Tunisia present relative continuity, Algeria is a very different picture. Already the most significant player economically, militarily, and in terms of human capital, the enormous popular dissatisfaction with the status quo throws into relief Algeria’s huge potential.

The incipient political transition may open opportunities for political pluralization, transformation of economic management, and market integration. Alternatively, it might unleash immense human suffering with security and trade shockwaves for the region. As such, the UK’s most pressing and important policy question for the Maghreb is how to address this great potential and considerable uncertainty.

One consequence of the current uncertainty for UK interests can be seen in legislation around hydrocarbons sector reform. Long-anticipated reforms to make foreign investment more attractive were passed in Algeria in late November.7 They were particularly sought by British businesses, which already have significant investments in the sector.

However, because of the deep popular disaffection with the Algerian administration, British businesspeople lack full confidence in the reforms. There is a fear that investments would be vulnerable if such reforms are rendered void by a successor government. Protestors agree with the need for reform of the hydrocarbons sector, but have objected to the way it was fast-tracked by the caretaker government.8 Similar concerns hover around the legitimacy and authority of the new president, enthroned in elections widely rejected by the protest movement.9 On the other hand, the new hydrocarbons law might represent a lifeline of cash infusion into the economy, return on investments, and a strategic economic prop.

Outside of the field of business, the potential for change is vast. Climate politics furnishes another example. Algeria is set to suffer some of the worst effects from climate change, with a projected increase in mean temperature of 2.6°C by 2050, and an increase in extreme weather events already evidenced.10 There is a reasonable level of awareness of this and the problems it could cause in Algeria. To date, the administration’s climate policies and climate diplomacy have been somewhat ineffective. Might a new administration be mandated to engage with this problem? And if it remains badly managed, what will the consequences be for national and regional stability? In Algeria, as elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa, desertification is linked to urbanization, itself an important trend in shaping the demographics of protest and unrest.11

Dealing with uncertainty

There is no way to resolve this tangle of uncertainty, so Algeria’s partners must prepare to respond to different eventualities. Being outside of the EU might strip the UK of some of its influence in the region, but it may in turn allow it to be more flexible and proactive toward the uncertainty in Algeria. One way of preparing for Algeria’s future is with the use of foresight, a business planning model now increasingly used for strategic policymaking. Foresight does not predict what is going to happen, but by drawing on the input of many different perspectives — from climate science and business intelligence, to economic forecasting and political science — it helps policymakers think creatively about the future. It can show where stabilization opportunities for the UK may lie in green technology, for instance. Such a project is under way with the Algerian Futures Initiative, which is bringing together many different perspectives to think creatively about Algeria’s future and what it means for its partners’ policies.12

It is quite easy within our dystopian zeitgeist to sketch a dark future for the Maghreb and British interests therein, but change in Algeria actually promises more for the region than it threatens. Algeria has the highest UN Human Development Index ranking in North Africa, its massive protest movement has remained peaceful for 10 months, and Algerians are interested in getting to know their neighbors to the north through cultural, educational, and governance projects. While foresight gets to grips with Algeria’s five-year trajectory, education, culture, and science are probably the best areas for British diplomacy to focus on.

At the end of November, Algerian businessman Yassine Bouhara exclaimed to the gathered members of the Algerian-British Business Council that Algeria — with a land mass the size of Western Europe and a farmable surface area as big as Spain — is not a country, but a continent. Rhetorical flourishes aside, among the countries of the Maghreb, Algeria has the greatest potential to influence the rest of the region, and indeed the African continent. British policy should attune to this.

Alex Walsh is an independent researcher in police reform and security in the Middle East. He has worked in security sector reform implementation and peace building on projects in Lebanon and Jordan, in program design and research. His current work takes a comparative look at opportunities for reform in police forces across the Arab World and the European Union’s role in the process.

Henry Peck is an independent researcher and author. He has contributed work to Guernica magazine, Human Rights Watch, National Public Radio, and elsewhere. The views expressed in this article are their own.

Photo by RYAD KRAMDI/AFP via Getty Images

Endnotes

1. Méditerrannée Afrique Co-développement is a non-profit organization that supports development by training and mentoring business people and entrepreneurs. http://medafco.com/partenaires.html

2. The World Bank Group, "Working for Algeria 2018," 2018. Accessed June 24, 2019 at http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/987321522058017988/Algeria-brochure-eng…

3. Figures for 2018 from DevTracker.gov.uk

4. Figures 2018-2019, figures from DevTracker.gov.uk

5. Figures found through average of amounts for period 2007-2017, original data provided by EU Aid Explorer

6. Figures for 2016-2017 from OECD

7. Slava Kiryushin, "Key changes in Algeria's hydrocarbon law: DWF," November 19, 2019, https://www.oilandgasmiddleeast.com/drilling-production/35596-key-chang…

8. Simon Speakman Cordall, "Algeria’s hydrocarbon reform adds fuel to protest movement," Al-Monitor, November 7, 2019, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/11/algeria-protests-hyd… l

9. For a particular viewpoint on this, see Karim Mezran and Alessia Melcangi, "Algerian election and legitimacy: Impossibility of change," December 17, 2019, Atlantic Council, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/algerian-election-and-…

10. World Bank Group, Climate Knowledge Portal: Algeria, https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/algeria/climate-da…

11. By this process, agricultural communities are no longer able to sustain themselves due to desertification, and individuals or small groups move to cities to find employment. In the cities, unemployment or underemployment remains a problem, and members of previously close-knit communities then have to grapple with social alienation in addition, thus building frustration and disaffection.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.