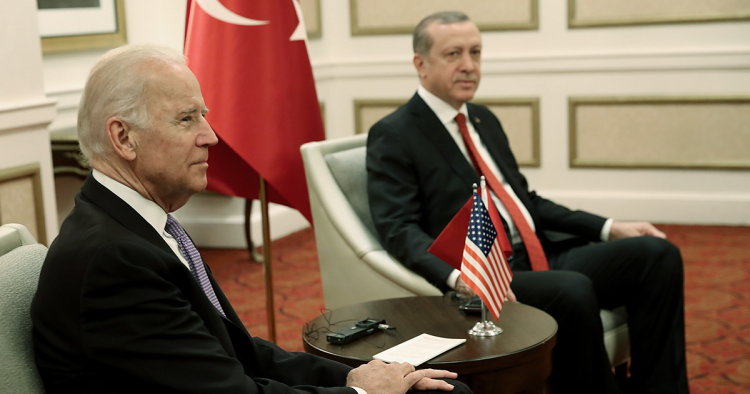

Relations between the United States and Turkey have never been worse, but the two countries still must deal with each other, and so President Joe Biden and President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan may talk this week. Each will review his list of issues. Both will commit to better relations and to best efforts to reach peaceful solutions to global, regional, and bilateral issues — and very little will change. The U.S. may emphasize NATO’s interests and welcome Turkey’s efforts to help find a way forward in Afghanistan. Turkey will highlight the fact of a direct conversation but will offer no new openings for the bilateral dialogue.

The global context

Turkey wants its own empire, and Mr. Erdoğan wants to celebrate the Turkish Republic’s 100th anniversary as president in 2023. Up to the end of World War II, ambitious countries made empires by seizing territory and resources. Now, nuclear weapons restrain great powers and even major regional powers from armed conquest. The post-World War II political and financial system, engineered by America and strengthened by Europe, gave priority to economic empires instead. The termination of the global colonial system, again stimulated by the U.S., began to level the field between developed and developing states, and that process still continues. The result is that the global economy has increased almost ten-fold since World War II.

The imminent collapse of the great power system, a theory widely promoted during the pandemic, is not evident. U.S., European, and Chinese economic revival is leading the way to the post-pandemic global economy. With Russia joining the military competition, now we have a four-way configuration in the years ahead. The good news is that none of these countries wishes to trigger a war among them, but the bad news is the difficulty of managing the inevitable lower-level conflicts: military, economic, and political.

The U.S. is a status quo power in this configuration. With 5% of the world’s population, its wealth will increasingly depend on international markets and the rules of an extraordinarily successful global system. Today, the European, North American, Japanese, South Korean, and Australian complex accounts for nearly 60% of global GNP. Yes, the Chinese economy may continue to grow, but it is not likely to rival that. Russia’s economy is about half the size of California’s and is heavily dependent on oil and gas exports, demand for which will decrease over time. The economic center of gravity of the world lies with this group of democracies and those who will want to join them in the decades ahead.

China and to some extent Russia are revolutionary powers that want to unseat the democracies for a number of reasons — economic, military, and political. They want to create a new world order on the theme that democracies are emotional, chaotic, trouble-making societies and what is needed in the world is order, certainty, and control. China, so far, has shown that wealth does not necessarily produce democratic change. Russia is pursuing its old maxim that weakening the opponent is strengthening the homeland, even if that means that its own people always live with less.

Choices come with consequences

In this world order, Turkey will make its choices. It could choose to be an ally of convenience (or more) with China and Russia to boost its regional ambitions. Russia is leveraging its victory in Syria, as horrific as it is, into greater influence in the Middle East and more dangerously in the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa. Moscow will continue to try to deepen European dependency on Russian energy and fragment the transatlantic bond. China’s Belt and Road Initiative has much appeal: cheap capital, access (on paper) to a vast market, and concrete results to build popular support in the borrowing country. In time, Russian and Chinese military presence globally may offer seductive comfort for countries linked to them.

Whatever Turkey decides, it will be responsible for the consequences. Often Turkey seems to cast itself as the victim, and thus others must make the concessions. Does Turkey think that will be true going forward, and, if so, for how long? Asserting one’s country’s concerns because of the natural growth of the economy is well understood. Doing so by asking your neighbors to give up their claims for yours is a different matter. What has Turkey gained with its interventions in the conflicts in Syria, Libya, and the South Caucasus? Why is the U.S. deemed an enemy? Is the U.S. more important as an enemy than as a friend? Does it matter for Turkish policy choices in the longer term that a congressional majority overrode a veto and required that sanctions be imposed? If economic choices discourage foreign investment in Turkey and speed up inflation and unemployment, is the demonstration of political will worth it? Has the effort to win over Russian concessions in Syria resulted in prosperity and security for Turkey? If Chinese goods are underselling Turkey’s own goods at home, and Turkey goes silent on the Uighurs, what leverage over Chinese choices is Turkey likely to create? Does the drive for independence risk creating a greater dependence?

At the moment, Turkey seems to seek the advantages while avoiding paying the price. The West, to which Turkey has ostensibly been attached, values the country and does not wish it to depart. But what price is the West willing to pay, and what costs does Turkey see ahead for the benefits it seeks? For how long can Turkey run with the hare and hunt with the hounds?

Ambassador (ret.) W. Robert Pearson is a non-resident scholar at MEI and a former U.S. ambassador to Turkey. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.