Amid the ongoing calamity of war in Lebanon, the country’s cultural scene is determined to work against the odds to keep its heritage and art alive. Among the many projects that are determined to push ahead is the Beirut Museum of Art (BeMA), a museum long in the works whose mission is to preserve the country’s heritage and culture through modern and contemporary art.

“We're still pushing forward because, in the end, this is a project that we believe needs to happen regardless of the situation,” said co-director of BeMA Juliana Khalaf. “In Lebanon, you never know when the time is right to do anything.”

There have been a number of additional setbacks since violence escalated sharply in late September. The Nuhad Es-Said Pavilion for Culture was due to open at the National Museum of Beirut on Sept. 19 with its first exhibition, “Portals and Passageways,” staged by BeMA until hundreds of pagers blew up across Lebanon two days prior in an Israeli operation against Hezbollah, killing several and injuring thousands. The inauguration ceremony was cancelled yet BeMA and the pavilion decided to open the exhibition regardless on Sept. 19. Doors are open daily, except on Monday, until it closes on Jan. 31, 2025.

Plans for BeMA, which was entrusted to curate the opening exhibition of the pavilion, were finished five years ago and it was scheduled to open this year but has been delayed repeatedly due to Lebanon’s financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. The facility, designed by Lebanese New York-based architect Amale Andraos, is now set to open its physical location in 2029 but has already staged numerous exhibitions in collaboration with other institutions of photography, calligraphy, restoration works, and performing arts. The “Portals” exhibition is the first being staged with contributions from the Lebanese Ministry of Culture (MoC), which has entrusted BeMA with around 2,000 pieces from its 3,000-piece collection to serve as the foundation of the museum’s offerings and will present a wide spectrum of artists and artworks portraying the history of Lebanon.

Unexpected bouts of violence and uncertainty are not new to Lebanon. Since the agreement with the MoC was signed calling for work on BeMA to begin in 2016, the Lebanese capital has been rocked by a series of escalating crises, including an economic collapse that the World Bank has ranked as among the world’s 10 worst since the 1800s and an explosion of hundreds of tons of ammonium nitrate in the Beirut port on Aug. 4, 2020, that killed hundreds of people, wounded thousands more, and caused billions of dollars’ worth of damage.

To add to the list of apocalyptic woes, since war broke out between Israel and Hamas following the terrorist attack on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, Lebanese have feared a full-scale war might engulf their country as well — a fear that has since become a reality. Following a sustained decapitation campaign targeting Hezbollah in late September, Israel launched an ongoing ground offensive into southern Lebanon on Oct. 1, destroying much of the south, and continues to carry out regular airstrikes in Beirut and across the country. The sizable death toll from the war and the constant sense of trauma, fear, and pain have transformed the lives of Lebanese residents, once again.

Fighting for art, against the odds

Against this dark landscape and sea of challenges, a group of Lebanese citizens, both in the country and in the diaspora, are determined to give Beirut a museum that celebrates its history and culture through modern and contemporary art. “No one wants to postpone anything; for us BeMA is a form of cultural resistance,” says Khalaf. “What we're building today is not only for today, but for future generations.”

The official groundbreaking ceremony for BeMA was held on Feb. 25, 2022. In the meantime, the museum has been operating out of a temporary structure in Fanar just outside of Beirut, complete with a lab for restoration and other offices for the education and research departments. It has also staged a series of pop-up projects around Lebanon and abroad, including exhibitions and events in Tripoli, New York, and Washington, DC.

At the helm of this incredibly passionate and determined enterprise are Lebanese women: co-directors Khalaf and Taline Boladian. Khalaf resides in Beirut and Boladian in Dubai with frequent trips to Lebanon. The founders of the project are Henrietta Nammour and Sandra Abou Nader, who have driven the museum since its inception in 2016. As president and vice-president respectively of the Association for the Promotion and Exhibition of Arts in Lebanon (APEAL), a non-profit based in Lebanon, they initially saw the opportunity to work with the MoC to realize the dream of establishing an arts museum in Beirut. Once the museum’s status was official, they transferred the core ideals of APEAL into the mission and vision of BeMA.

BeMA USA is registered in the United States as a nonprofit with 501c status. The museum and its programs are being built entirely from private funding and donations from Lebanon and internationally. “Nothing has come from our own government, nothing at all,” says Boladian. The museum’s mandate is to foster cross-cultural dialogue and collaboration between the Lebanon and the US while also working to advance the development of BeMA, regardless of the challenges. “We often get this very dumbfounded look when we say we’re building a museum in Lebanon amidst this crisis, with hungry mouths to feed, no gas and no electricity,” Boladian said during a panel about the project held at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in November 2022.

While construction of the dedicated building is taking place, BeMA continues to advance its educational programs in Beirut in the realm of cultural expertise, professional training, and collaboration through its "Beyond the Walls" programs in dialogue with past and present artistic voices. “The founders firmly believe that a museum can and should live outside its walls, and secondly, that its programming should be in place prior [to] its physical opening,” explained Boladian.

Since 2016, BeMA has been running programs to enhance the lives of Lebanese through various artistic initiatives, often with little fanfare. “Much of our work is done in the spirit of collaboration and regeneration to weave a thread through different collections across Lebanon and raise awareness for the museum,” said Boladian. Activated first was BeMA’s restoration program designed to restore 920 artworks and clean more than 2,500 others in the museum’s inventory. Since 2017, BeMA has worked with Kirsten Khalife as the head restorer who runs the program and has completed the restoration of over 200 paintings through grants from the Getty Foundation and UNESCO, trained two staff members, and run exchange programs with Stuttgart University as well as directed workshops on new methods for restoration. The program suffered a setback due to the 2020 Beirut port explosion — while no works were damaged, some needed to be recleaned. Khalife and BeMA also participated in the cleaning of art in Beirut’s Sursock Museum affected by the explosion.

Khalaf and Boladian have also established two essential programs: the Research Department, headed by the museum’s artistic director, Clemence Cottard Hachem, who is responsible for researching the Ministry’s collection and creating a database, an exhibition, publications, and guidelines for the future; and the Archives and Digitization Department, which is helmed by Lebanese photographer Mahmoud Merjan, who is responsible for digitizing the artworks, a process that requires photographing the pieces themselves and the artists’ signature to create a digital database.

The museum was initially established without archives on which to test the development of programs and policies. To jumpstart the archival system, BeMA entered into an agreement with renowned artist Samir Sayegh to begin digitizing his artworks — the digital version of which will belong to BeMA and serve as a tool for future researchers. BeMA believes that its archives and database eventually will become a source of income for the museum. In 2024 the museum received six archives contributed by artists’ families.

Unveiling a hidden collection

The crown jewel of BeMA is its permanent collection, which consists of approximately 2,000 works by 300 artists drawn from the MoC collection. The museum will display these works to the public for the first time in the collection’s 100-year-old history via pop up exhibitions until its official opening in 2029.

The collection was first assembled during the 1920s by philanthropist Viscount Philipe de Tarazi and was then continued by the MoC in 1954 over a period spanning decades with the mission of creating a national repository. Among the works that will be unveiled are exceptional examples from the French mandate era (1920-43) by artists influenced by the European avant-garde of the time, including Moustafa Farroukh and Marie Hadad. Also included are pieces that were created after Lebanon’s independence from France in 1943, reflecting a desire to create a national, naive aesthetic by artists such as by Khalil Zgaib.

With the earliest work dating to 1880 and the latest to 2015, the collection traces the work of Lebanese artists through the art movements of Classicalism, Modernism, Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, Surrealism, the influence of the Lebanese Civil War and the post-war period, and the Contemporary era. On view will be works by Amine el-Bacha and artists that represent the influence of American Abstract Expressionism, while others showcase the horrors of the Lebanese Civil War as interpreted by artists including Mahmoud Zein el-Din and Hassan Jouni.

“Although the museum will show up to 600 pieces at a time, the selection was made broad enough to allow for a future curator to make his or her own selection for the permanent exhibitions,” explains Boladian. Works are chosen for inclusion based on a synthesis of five factors, including the importance of the artist, rarity and period of the piece within the artist’s career, condition of the work, technical skill of the artist, and the subject matter. “The collection offers a complete overview through art of modern Lebanese history that has never been available to the public before,” added Boladian.

A museum for hope, healing, and a creative economy

Lebanon is a country whose fate has long walked a shaky tightrope, raising questions about the viability of such an ambitious initiative. While fears over the scale and duration of the war hang in the air, the directors of BeMA have refused to give up on their plans. This is not just because a first-class art institute is long overdue for a country with a rich cultural heritage and an impressive collection that has been assembled over 100 years representing the depth and talent of Lebanese modern and contemporary artists, but because art, they believe, has the power to unite and heal people during times of conflict and its aftermath.

The directors of BeMA have taken a leadership role in the development of Lebanese artistic and cultural communities. “We need to help professionalize workers in the cultural industry,” says Khalaf. “Not only for us, but for other institutions that are in need. ... We also want to limit the brain drain from Lebanon.” They believe such initiatives activate, even if on a small scale, the national creative economy, and are pushing ahead, despite the current dark mood. The 2020 port blast decimated entire neighborhoods, such as Mar Mikhael and Gemmayzeh, where many creatives had studios and boutiques and where restaurants and hotels thrived. A visit there today will find such places rebuilt and new locations opened, with Lebanese creators doing business at home and overseas.

“We want people to know that there are job opportunities in a sector like the arts and culture in Lebanon,” adds Khalaf. “Often in Lebanon, people think that they can only find jobs as lawyers, engineers, and architects, [but] there really are many of opportunities within the cultural sector, such as the roles of researcher, archivist, exhibition coordinator, restorers, and scientific conservators.” Toward that end, BeMA has recently established a partnership with the American University of Beirut (AUB) and Saint Joseph University (SJU) to encourage and train science students to become art conservators.

Another way in which BeMA is transcending the hardships of Lebanon and fostering cultural regeneration, a creative economy, and a sense of community is through its art education programs that engage young students across the country from various religious and socio-economic backgrounds. “The public sector has suffered tremendously to the point that some public schools even remained closed after COVID,” explained Khalaf. “We continued doing our programs within the schools and realized that many soft … skills were obtained during the process.” The by-product of these programs, Khalaf and Boladian realized, is that not only were the children in these workshops enhancing their creative skills but were also learning to work together in a positive environment despite their differences.

The same can be said for the psychologically therapeutic process of people coming together, from various backgrounds but subject to the same traumatic experiences, to create and view Lebanese art in the future BeMA facility.

The museum, its founders and directors believe, offers a source of national pride and identity during a time of crisis. It offers a way to have faith in the future despite the past.

“In light of the ongoing crisis, we are taking proactive steps to map endangered archives and collections in high-risk zones to preserve and protect cultural heritage,” said Khalaf. “Additionally, we are adapting our public school program to better support teachers by offering specialized training that includes art therapy and trauma components, providing essential tools to help educators address the emotional and psychological needs of their students during these challenging times.”

Art for BeMA, even during this moment of utmost catastrophe and hardship, remains a way to preserve hope and humanity.

“We are hoping through the content of the art we're presenting that we are reminding people that there's still something to be proud of,” she adds. “There is a common identity, there is a common heritage, and we should still fight for it. It is just a reminder that there is something healing about remembering what is still good, what we still have and that’s worth fighting for.”

Rebecca Anne Proctor is an independent journalist, editor, author, and broadcaster based in Dubai and Rome, from where she covers the Middle East and North Africa. She is the former editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar Art and Harper’s Bazaar Interiors.

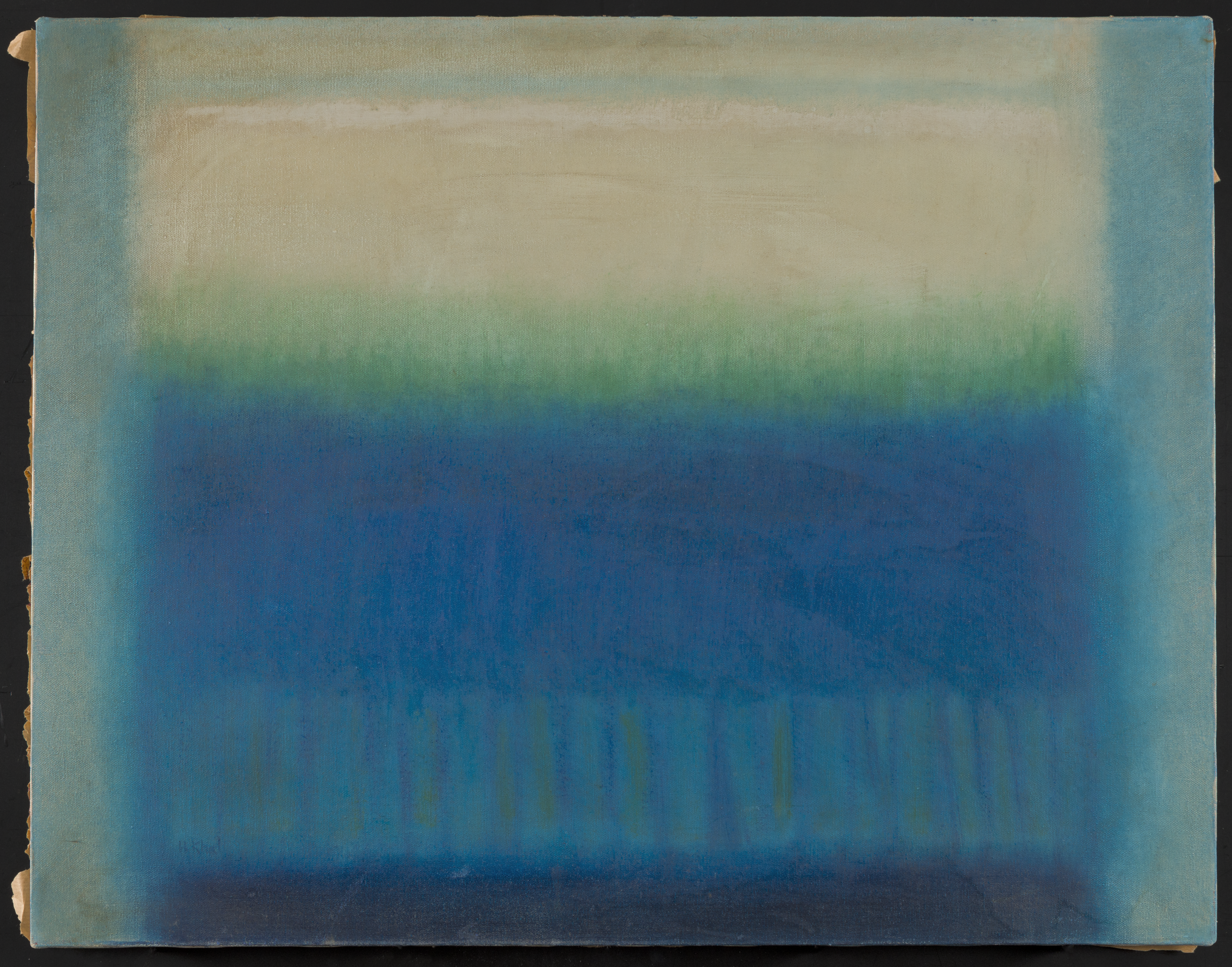

Top image: Hymne à l'amour by Alfred Tarazi, Courtesy of Laetitia el-Hakim

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.