The Gulf states are often overlooked as indirect beneficiaries of the Russia-Europe energy war. In what ways and to what extent have they leveraged it? Are these benefits sustainable?

The current energy war between Russia and Europe predated, but was markedly intensified by, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The protagonists are deploying a range of energy weapons aimed at increasing the costs of escalation or remaining in Ukraine (for Russia) as well as of defying Russia’s actions in Ukraine (for Europe). These have upended global energy trade flows and increased energy prices in 2022 relative to the past several years; they have also impacted a wider range of non-energy goods and services as well as diplomatic ties.

Given that energy — its affordability, availability, and sustainability — underpins modern civilization, the question “who is winning the energy war?” is a pertinent one. Claims that Russia is the victor are countered by assertions that this is a “myth” since Moscow faces “economic oblivion” and permanent decline as an energy superpower. A more nuanced perspective argues that while Russia may be a short-term winner, Europe will triumph in the energy war over the long run. Apart from the protagonists, India and China are also frequently cited as winners given that they are major energy importers that have benefitted from discounted inflows of Russian fossil fuels shunned in Europe. Very few analyses, though, speculate on the benefits of the energy war for the Arab Gulf states or the mechanisms through which they have benefitted, deficits this article tries to correct.

Mechanism #1: Arbitrage

Some Gulf states have leveraged the energy war by engaging in arbitrage. This refers to substituting cheap Russian fuel oil for domestically produced oil used in power plants to generate electricity, thus freeing up more domestic oil for export to Europeans trying to reduce their dependence on Russian crude oil and oil products. The practice is mostly limited to Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, where oil accounted for 39% and 41.5% of power generation respectively in 2020. A study in October 2022, for example, noted that the increase in fuel oil consumption during summer 2022 did not result in a decline in Riyadh’s oil exports because unusually large volumes of Russian fuel oil, more than twice as much as the same period in 2021, were being imported (directly and through other ports) and burned in place of domestic oil.

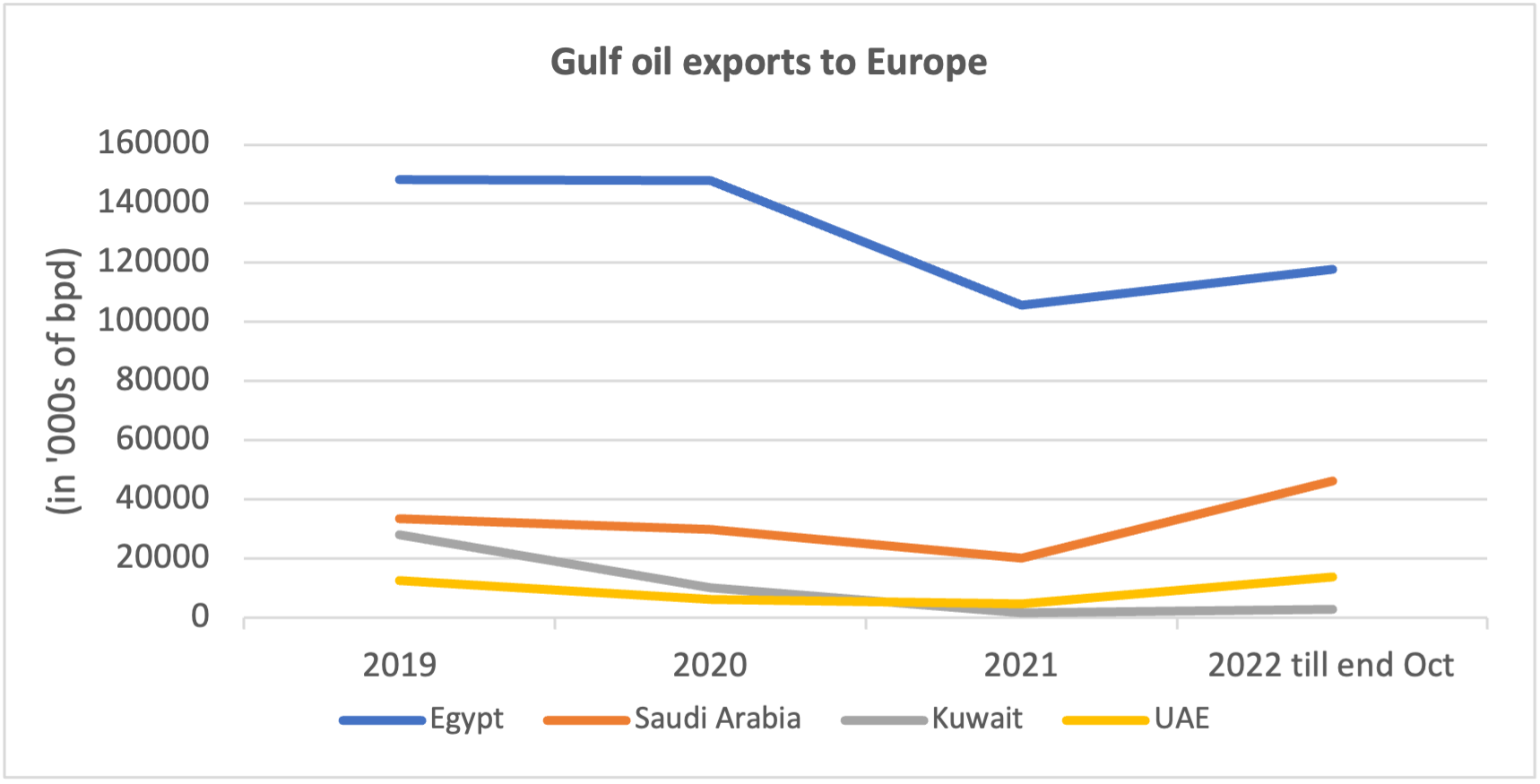

At the same time, higher volumes of Saudi (and Gulf) oil found their way to Europe in 2022. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Kuwait exported more oil to Europe during the first 10 months of 2022 compared to 2021 (see chart 1); in the case of Saudi Arabia and the UAE, more oil was sent to Europe between January and October than in all of the past three years combined. The similarity of Gulf crude, particularly Saudi Aramco’s Arab Light, to Russia’s Urals crude makes the former a good substitute. Unsurprisingly, Europe’s share of Saudi oil exports between January and July 2022 increased to 20-25% of total oil export revenue, up from 10-15% in previous years.

Although European sales are a short-term fillip for Gulf economies, Europe’s declining oil demand — underpinned by electrification of vehicles and public transport; fuel efficiency requirements for maritime, air, and road transport; and estimates that it hit peak oil demand in 2005 — renders the continent a relatively unattractive long-term market for Gulf exporters compared to Asia and Africa.

Chart 1: Exports of Gulf crude oil and petroleum products to Europe

Note: Oil exported from Egypt’s Ain Sukhna terminal is connected to and originates from Yanbu in Saudi Arabia. Source: Refinitiv Oil & Shipping Research

Mechanism #2: Nativizing Russian oil for onward export

A second way Gulf oil exporters have monetized the energy war to their benefit is by importing Russian oil for blending/re-export to South Asia and Europe. Imports of Russian crude and oil products have increased significantly since February, with Oman and the UAE importing more Russian oil in the first 10 months of 2022 than in the past three years combined (see chart 2). Indeed, Russian vessels unloading their cargoes were blamed for causing congestion at the port of Fujairah during summer 2022. Savvy Gulf refiners are likely to take advantage of the loophole in European Union legislation set to come into effect on Feb. 5, 2023 that allows oil products exported from refineries in the Gulf (or other refining hubs) but fed by Russian crude to escape EU sanctions since Russian crude is deemed to have been “substantially transformed” through the refining process.

With Europe desperate for non-Russian oil products such as diesel, a situation made more acute by the closure of some U.S.-based refineries in the past few years, products from Kuwait’s newly expanded and upgraded al-Zour Refinery, which recently sent its first shipment to Europe of aviation fuel, as well as from Abu Dhabi’s Ruwais refinery, which is due to be fully commissioned in 2025, will find willing buyers on the continent.

Chart 2: Gulf imports of Russian oil

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 (till end Oct) | |

|

Oman Crude (barrels) Products (tons) |

0 195 |

0 111 |

0 0 |

0 338,030 |

|

UAE Crude (barrels) Products (tons) |

0 353,000 |

725,400 310,000 |

0 34,000 |

3,205,000 1,494, 210 |

Source: Refinitiv Oil & Shipping Research

The nativization tactic is also feeding speculation that at major transhipment hubs such as Fujairah, oil cargos could be delivered by Russian ships, reloaded onto ships flying non-Russian flags, and then delivered to European ports as Fujairah-origin oil. This practice, which takes a page out of the sanctions evasion playbook of Iran that rebrands oil sold to China as “Malaysian” following a port call in Malaysia, is likely to be a win-win for Russia and the UAE. For the latter, though, there is a risk that Dubai’s reputation as a major hub for illicit trade will only worsen.

Mechanism #3: LNG diplomacy with Europe

Oil aside, the energy war is also facilitating a broadening of the Gulf’s client base for liquefied natural gas (LNG) to include more European customers beyond the United Kingdom, Italy, and Spain.

Hitherto, smaller LNG exporters from the Gulf, namely Oman and the UAE, had focused almost exclusively on Asia due to Russia’s stranglehold on pipeline gas exports to Europe and the higher premiums commanded by LNG in northeast Asia. As for Qatar, while Europe accounted for 15% of its LNG sales in 2021, Asia was still its dominant market with a share of nearly 80%. The energy war has, however, starkly reiterated Russia’s determination to weaponize Europe’s gas dependency and let the continent “freeze, freeze” in contrast to Qatar’s depoliticized approach, whereby it continued to sell contracted gas quantities to the UAE despite the latter participating in a 43-month-long blockade against it. One measure of the success of Qatar’s LNG diplomacy is the fact that Europe’s share of Qatar’s LNG sales by revenues jumped to one-fifth of the total in the second quarter of 2022 compared to 10-12% in the same quarter during previous years; this was largely a consequence of higher spot LNG prices in a Europe frantically trying to fill gas storage ahead of winter as opposed to higher LNG volumes.

More significantly for Qatar’s long-term LNG ambitions and with this its global influence is the 15-year agreement concluded in November 2022 by Germany with state-owned QatarEnergy for the supply of 2 million tons of LNG annually from 2026. The deal, which was hailed by the Gulf state’s energy minister as “first ever long-term LNG supply to Germany,” appears to be a significant concession on Qatar’s part since its preference was for a much longer period akin to the 27-year deal to supply China’s Sinopec with LNG signed a mere eight days earlier. Equivalent to about 6% of the volume of Russian gas Germany imported in 2021, the QatarEnergy deal will not completely replace Russian gas but may encourage utility companies in other European countries to conclude their own offtake arrangements with Doha, which is itself seeking buyers for its expanding LNG production. The UAE is also likely to target European markets to monetize the costly development of its sour gas fields and the construction of a new and second LNG export terminal, both of which were planned prior to 2022.

Notwithstanding the Gulf’s thus far successful LNG diplomacy in Europe, the recent threat by an unnamed Qatari diplomat that investigations into the country’s alleged bribery of EU parliamentarians could “negatively affect” ongoing energy negotiations will test Qatar’s reputation as a reliable and apolitical LNG supplier.

Mechanism #4: Renewable energy diplomacy with Europe

One of the expected outcomes of the energy war is a massive ramping up of the deployment of renewable capacity across Europe to boost energy self-sufficiency while reducing reliance on fossil fuels and Russian energy in particular. For instance, following discussions that began in May 2022, both the European Parliament and European Commission have endorsed increasing the target for renewables in Europe’s energy mix from 40% to 45% by 2030 as part of the REPowerEU plan. For the Gulf states, investing in European renewable energy projects demonstrates policy alignment, which in turn facilitates goodwill for sales of Gulf hydrocarbons that will continue to be required during the energy transition.

In this regard, in October 2022 the Qatar Investment Authority, the country’s sovereign wealth fund (SWF), agreed to invest in RWE, a major German utility, to support its plans to embrace green electricity as its core business. In return for partly funding RWE’s acquisition of renewable energy assets from a U.S. energy company, QIA will receive around 9% of RWE’s shares. The deal is likely to improve prospects for finalizing ongoing gas supply negotiations between QatarEnergy and RWE. As for the UAE, the acquisition in October 2022 of an undisclosed stake by Abu Dhabi’s SWF Mubadala in Skyborn Renewables — an offshore wind developer based in Germany with a global portfolio of projects — coincided with the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company’s (ADNOC) agreement the previous month to send LNG and diesel to Germany in late 2022 and 2023.

To be sure, the renewable energy investments cited above were clearly driven by a strong business case that includes diversifying investment portfolios of SWFs and gaining expertise in renewable technologies. These states, through their respective parastatals, had invested in renewable energy projects in Europe prior to the outbreak of the energy war, including London Array and Hywind Scotland by Masdar, a subsidiary of Mubadala, as well as solar parks in the Netherlands by Qatar-owned Nebras Power. But equally, it does not hurt the Gulf states to be seen to support Europe’s net-zero ambitions while plying the continent with oil and gas.

Mechanism #5: Strengthen ties with Russia

In addition to positive engagement with Europe during the energy war as discussed above, the Gulf states have also maintained good relations with Europe’s nemesis, Russia. They have done so in two ways, the first of which is through the OPEC+ platform. A long-standing Russian foreign policy goal is to be acknowledged, recognized, and treated as a great power. By declining to seriously entertain suggestions that OPEC+ should exclude Russia from monthly quotas in response to difficulties with oil production caused by voluntary and official sanctions — and hence increase the scope for Gulf states to pump more oil at Russia’s expense — the group’s key power brokers, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, are reiterating their belief about Russia’s enduring significance for oil markets and regional conflicts. They also have little interest, and perhaps limited capacity, to substantially increase oil output since this would put downward pressure on oil prices. Even the UAE, which had previously chaffed at OPEC+ quotas that limit its plans to increase oil production capacity from 4 to 5 million barrels per day (mbpd) by 2025, declared in March 2022 that Russia will “always” be part of OPEC+.

This is because even with the loss of oil production due to sanctions — estimated to be between 0.85 and 1.4 mbpd during the first quarter of 2023 — Russia will still be the second-largest producer within the group by far. This means that should oil prices nosedive in the future, OPEC+ will need Russia’s cooperation to stabilize prices.

The second pathway through which the Gulf is maintaining good relations with Russia is by refraining from a cut-throat price war in Asia. The latter is a market traditionally dominated by the Gulf states, but has recently become one of the few viable markets for Russian hydrocarbons. Russia has been China’s top supplier for several months, with exports rising to 1.9 mbpd (or by 17% in November 2022 compared to a year ago) compared to Saudi Arabia’s 1.6 mbpd (or down 11% from a year ago). Russian crude oil, sold at discounts that range between $23 and $35 per barrel to benchmark Brent crude prices, are simply too good to pass up for price-sensitive China; the EU price cap imposed in December has only encouraged Asian buyers to seek further discounts from Russia. Nevertheless, Saudi Arabia is not unduly worried partly because fierce Saudi-Russia competition in China has been ongoing for several years. Saudi Arabia is still just ahead of Russia as China’s top supplier for the first 11 months of 2022 and may take comfort from President Xi Jinping’s pledge last month to “expand the scale of crude oil trade” with Riyadh and other Gulf states, particularly, one assumes, if purchases can be settled in yuan instead of the dollar. Beijing’s practice of diversifying its sources of imported hydrocarbons also precludes over-dependence even on cheap Russian oil in the long run.

In India, Asia’s second-largest oil importer and one that is dominated by supplies from Iraq and Saudi Arabia, imports of Russian oil have ballooned 14-fold since March 2022. This has increased Russia’s market share to around one-fifth compared to less than 3% historically. To protect its largest market, Iraq has undercut the price of Urals in India by an average of $9 per barrel, but Saudi Arabia appears unfazed since higher Russian volumes have been at the expense not of Saudi crude but those from the U.S. and Africa. In the long run the sustainability of the Russia-Indian oil trade is also challenged by the long-term decline of Russia’s oil industry, an issue even before the current round of Western sanctions, along with high freight costs and voyage times between Indian and Russian ports.

Mechanism #6: Financial windfall

Finally, the economic health of the Gulf states — and in particular those that undertook reforms to improve competitiveness, regulatory efficiency, and workforce inclusivity over the past several years — has benefitted from the energy war. The windfall from higher hydrocarbon prices relative to previous years, amounting to around $1 trillion between 2022 and 2026 for the Middle East oil exporters, is likely to result in budget surpluses in 2022 for all Gulf states with the exception of Bahrain, an insignificant oil exporter. The fiscal surplus is a first for the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) as a group and for Oman since 2013 while it will be the second in as many years for the larger exporters Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The Gulf states are also likely to be outliers in terms of GDP performance: According to estimates by the World Bank, the GCC is expected to outperform global GDP growth in 2022 and 2023. Meanwhile, inflation will be kept at bay by a fixed peg to the U.S. dollar for five of the six states (with Kuwait maintaining a looser peg) thereby mirroring interest rate rises in the U.S., by price controls on a broad range of basic food items, by the provision of highly subsidized energy (albeit to a lesser extent in the UAE), and by increases in already generous subsidies to low-income citizens.

The financial windfall should, in theory, augment the basis for the social, political, and regional peace required to attract foreign talent and private investment as well as to reform structural rigidities that plague Gulf economies. The extent to which long sought-after economic diversification plans by all Gulf states can be realized remains to be seen; after all, opportunities presented by the previous oil boom during the early 2000s were mostly squandered.

The UAE as a leading beneficiary

It is the UAE that stands to benefit most from Europe’s energy war, much more than its Gulf peers. The UAE will continue to take advantage of the inflow of Russian money, including tourists, real estate purchases, and establishment of local units of Russian commodities and energy companies locked out of doing business in Europe and the U.K. This is because sanctions once imposed tend to be sticky and difficult to remove; moreover, there is a strong consensus among political and business leaders in Europe to never again be as energy dependent on Russia. The UAE has also been mindful to appear to address concerns in EU and U.S. policy circles regarding support for Russia. For instance, in September 2022, UAE-owned banks in Turkey suspended acceptance of a popular Russian card payment system; a UAE bank also declined to accept dirham-denominated payment in place of dollars for Russian oil purchased by Indian refiners.

More significantly for the UAE, it will be able to tout and credibly deliver on its green energy credentials, thereby aligning itself with the EU’s Green Deal to be climate neutral by 2050. As a trade partner that is able to provide exports with low carbon intensity — hence reducing the deficit created by the potential exit of energy-guzzling European steel and chemical manufacturers — the UAE is likely to increase its market share in Europe for selected products.

Unlike its Gulf peers, the energy used to produce offshore oil by ADNOC will soon originate from low carbon sources thanks to the ongoing construction of a subsea cable that will deliver electricity from the mainland’s nuclear and solar power plants. In the case of aluminum, the UAE already accounts for 6.6% of the EU’s imports, making it the bloc’s sixth-largest source of imported aluminum. Emirates Global Aluminium (EGA), the UAE’s largest company outside of the hydrocarbon sector, is targeting a significant increase in the production of premium green aluminum (through the same low carbon energy sources) used mostly by car parts manufacturers in Europe for high-end vehicles. By comparison, Bahrain’s ALBA, the world’s largest aluminum smelter, is constrained in its ability to follow suit by the country’s fiscal capacity and territorial size, which limits deployment of utility-scale low carbon energy sources. As for Emirates Steel Arkan, it is making good progress in research to manufacture greener steel by incorporating the use of green hydrogen into the steel making process. Already, it boasts a lower carbon footprint than most of its competitors in China and India thanks to the use of natural gas instead of coal as well as the deployment of electric arc furnaces, whose carbon intensity is 75% lower than traditional blast furnaces. With imports of Russian steel already banned in the EU and with imports of Turkish steel processed with semi-finished Russian steel set to be banned later this year, UAE steel companies should be able to make some gains in the EU at the expense of the latter’s two largest sources of steel imports.

Other Gulf states are beginning to address the issue of embedded carbon in their products, with Qatar announcing that the expansion of its LNG production capacity (from which German utilities are likely to be offtakers) will be accompanied by technology to capture and sequester associated carbon emissions, thus meeting European requirements. Nevertheless, it is the UAE that has a clear first mover advantage among the Gulf states. The fact that Dubai and Abu Dhabi have been operating for a number of years an internationally recognized certification scheme that tracks and verifies every megawatt of low carbon electricity claimed by ADNOC, Emirates Steel, EGA, and other companies is also likely to be appreciated by customers in Europe.

Li-Chen Sim is an assistant professor at Khalifa University in the UAE and a non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute in Washington, DC.

Photo by Simon Dawson/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.