In recent years, China has become increasingly involved in the international arena, including the Middle East. As a rising superpower, China finds itself, time and again, needing to maintain relationships with countries that are hostile to one another. This is particularly true in the Middle East, which is one of the most conflictual areas in the world. Even before China gained its current influence, it encountered this issue during the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-88, when it armed and maintained diplomatic relations with both sides. Fast forward to the present and China now faces a similar challenge as it seeks to maintain good relations with both Iran and Israel, two of the region’s fiercest and loudest adversaries. How does Beijing manage to do this, and can it continue to do so going forward?

To summarize China’s approach, it puts economics first — ahead of political, ideological or humanitarian interests and sympathies. Whenever possible, it avoids choosing sides in rivalries or conflicts. China’s international actions are driven by the country’s needs, which is why it maintains good relations with both Iran and Israel. Above all else, Beijing is focused on growing its economy in order to raise living standards and maintain internal stability. Realist analysts of international relations would argue that China is not to be faulted — and is even to be praised — for choosing partners based on self-interest rather than ideology, regime type, or humanitarian concerns. All countries prioritize their own national economic and security interests to a certain extent, and doing so sometimes requires maintaining positive relations with countries that are hostile to one another. The U.S. does this, as do European nations — between the U.S. and Russia, for example — and so too does Israel, which is a major supplier of arms to China’s rival India. What makes China different from most countries is that the scale and range of its actions define the international order.

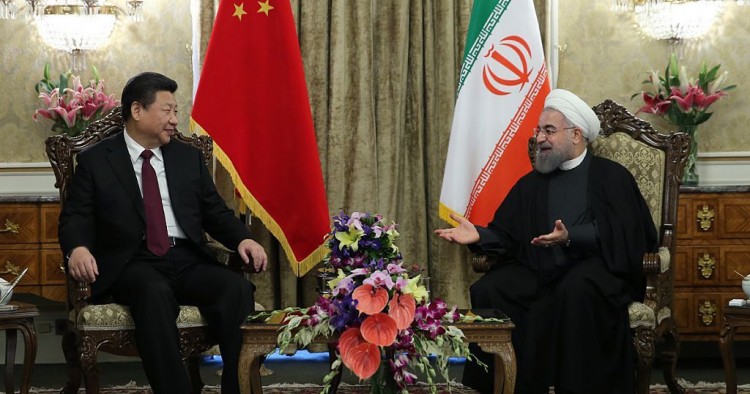

China and Iran: Securing cheap natural resources and countering American hegemony

As revealed by The New York Times, Beijing and Tehran have recently been discussing a major deal — one that would potentially see China invest as much as $400 billion in Iran over 25 years — because China perceives Iran under the current U.S. “maximum pressure” sanctions regime as a “distressed asset” that it can tap into for a low price to enhance its energy security and expand its export market. But best of all for Beijing, it can leverage this “distressed asset” to challenge the U.S. position in the Middle East: If Iran proves that countries subject to U.S. sanctions can ride out the economic impact by leaning on China, one of America’s strongest tools for pressuring foreign powers will be blunted. Countries in the Middle East and around the world will be less likely to appease the North American hegemon if they can rely on an alternative power like China that is indifferent to its partners’ internal political arrangements. China also seeks to undermine Donald Trump's strength in the international arena in the critical run-up to the U.S. presidential election in November.But it seems clear that the China-Iran agreement has more to do with Chinese-U.S. long-term great power competition than short-term tactics against the sitting president or even China’s energy security or trade markets, which would be only marginally affected by the accord.

Put simply, China can import energy from many other sources and expand trade with markets that are more stable, offer greater promise, and create less controversy. But instead it has chosen Iran — not because it needs to, but because it wants to and it can. Beijing is quick to jettison Iran when convenient, however. For example, in order to encourage the progress of trade negotiations with the U.S. earlier this year, Beijing swiftly reduced its oil imports from Iran — by 89 percent year-on-year in March — as a gesture of goodwill toward the Trump administration. In June, China imported no crude oil at all from Iran, even as its imports from Saudi Arabia reached an all-time high. Since then, however, China has reversed course, importing 120,000 barrels per day of Iranian crude oil in July.

China and Israel: Drawing from “Silicon Wadi”

In the World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Report 2016-17, Israel was ranked as the second most innovative nation in the world after the U.S. China has invested heavily in the Israeli high-tech industry (known as “Silicon Wadi”) in recent years, and the two countries hold an annual technology innovation and investment summit. China is driven by a desire to outpace the U.S. to become the world leader in developing 5G and other advanced technologies. Israel, alongside Canada, Denmark, Greece, Japan, Norway, Taiwan, England, Slovenia, and other states, is poised to ban Huawei products from its 5G network in response to sustained U.S. pressure under the so-called “Clean Network” plan. However, China still views Israel as an innovative technology hub with which it can cooperate to meet its own needs and objectives. Like Iran, Israel is a “nice-to-have” partner, not a “need-to-have” one.

Of course, Israel is not the only exporter of high-tech products to China. Other countries develop innovative technology and China’s own technology ecosystem has become fairly advanced as well due to considerable local investment. When it comes to technology, the most important country for the Chinese economy is still the U.S.: American universities taught 171,000 Chinese STEM students in 2018-19, its huge market imports over $500 billion worth of Chinese goods annually, and — perhaps less tangible, but no less important — the exchange of ideas and competition between the two countries drives technological growth and development. So the only “must-have” relationship for China is with the U.S. China can maintain and strengthen ties with both Iran and Israel without feeling any moral unease, since these relationships are based on common interests, not shared values or mutual dependence. Beijing can maintain both of these relationships precisely because they are not "must-haves”; it can always balance them according to changing needs and cut ties with one of the countries if it objects too strongly to China’s relations with the other.

Moving forward, as China’s influence continues to grow, Beijing’s strength is likely to reshape the international arena. One of the major changes will be a wider margin of maneuver for countries that oppose the U.S., which has long been accustomed to its status as the sole superpower. Iran is only one example, and it will not be a surprise if other states that oppose American hegemony also receive support from China, even if they have no specific resources or obvious strategic advantage to offer Beijing. This “take-all-comers” approach from China marks an epochal shift in international affairs. In the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s collapse, few if any countries could afford to risk exclusion from the emerging Liberal world order by balking at American demands for democratization, financial liberalization or disarmament. Since the early 2010s, a new superpower has been rising and from its partners — countries as diverse and mutually antagonistic as Israel and Iran — it demands only one thing: profit. Many other countries might take this bargain, as the one thing that China demands it also offers. The more these two superpowers develop into isolated systems, the more the world has to worry about escalation. Today, these two superpowers depend on one another, but if at some point this changes, escalation will be rapid.

Roie Yellinek is a a non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute, a Ph.D. student at Bar-Ilan University in Ramat-Gan (Israel), and a doctoral researcher at the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by Pool/Iranian Presidency/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.