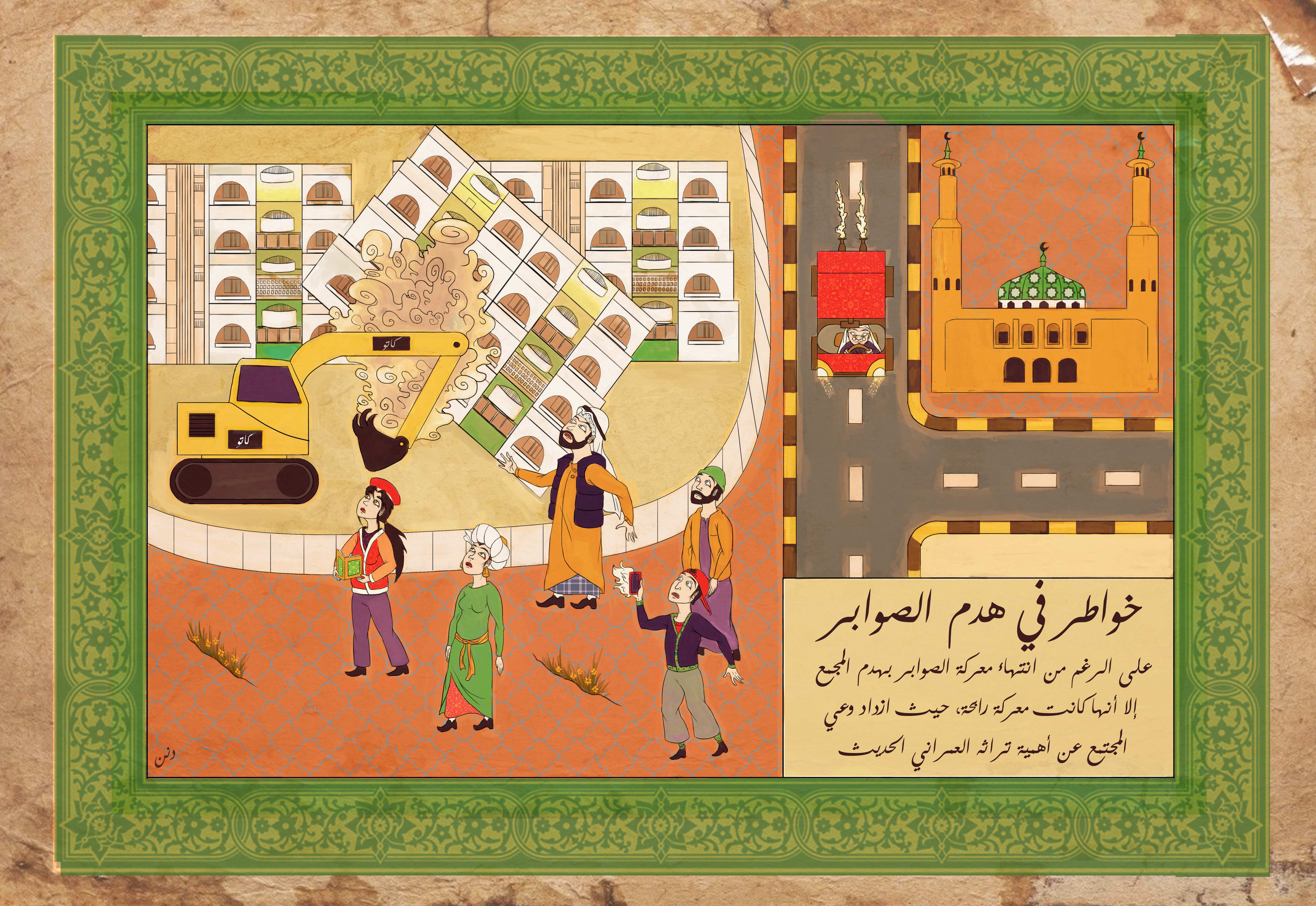

On Sept. 29, the Khaleeji Art Museum — the first digital museum dedicated to art from the Arab Gulf States — opened its latest solo exhibition, Architecture of Memory, which showcases a collection of digital paintings and animations by emerging Kuwaiti artist Dana Al Rashid. Upon visiting the digital exhibition, visitors are welcomed by On the Demolition of Al Sawaber, a painting in modern miniature style that depicts a group of onlookers from different eras staring in shock and horror as they witness the demolition of the Al Sawaber Complex.

Designed by Canadian architect Arthur Ericson in the 1970s and completed in the early 1980s, the Al Sawaber Complex was Kuwait’s first multi-story form of social housing. Over the decades, not only did the residential complex composed of 33 buildings become home to hundreds of families and individuals, it also became known as “a modernist gem in a hectic city” because of its futuristic design. When it was under the threat of demolition in the last decade, many protested the decision, including academics, architects, and activists, who called for the complex to be preserved or repurposed given its status as a historical building of the modern era. In addition, numerous artists and photographers, such as Kuwaiti artist of Palestinian origin Tarek Al Ghoussein, took to documenting the complex and the diverse lives it housed before it disappeared forever in 2019.

Since then, the tale of the demolition of modern architectural heritage in spite of public resistance has repeated itself time and again in Kuwait, as highlighted by the works in Architecture of Memory, especially On the Demolition of Al Sawaber. The exhibition of 14 digital paintings and animations tells the story of the construction and reconstruction of modern Kuwait, which began in the late 1940s, after the country experienced an oil-driven economic and cultural boom. During that time period (i.e. the late 1940s to the early 1980s, which is popularly dubbed the “Golden Era of Kuwait”), the rising nation state commissioned international architects to design buildings that would mark its transition into the modern world, such as the iconic Kuwait Towers and Kuwait Water Towers, which are depicted in five of Al Rashid’s exhibited works.

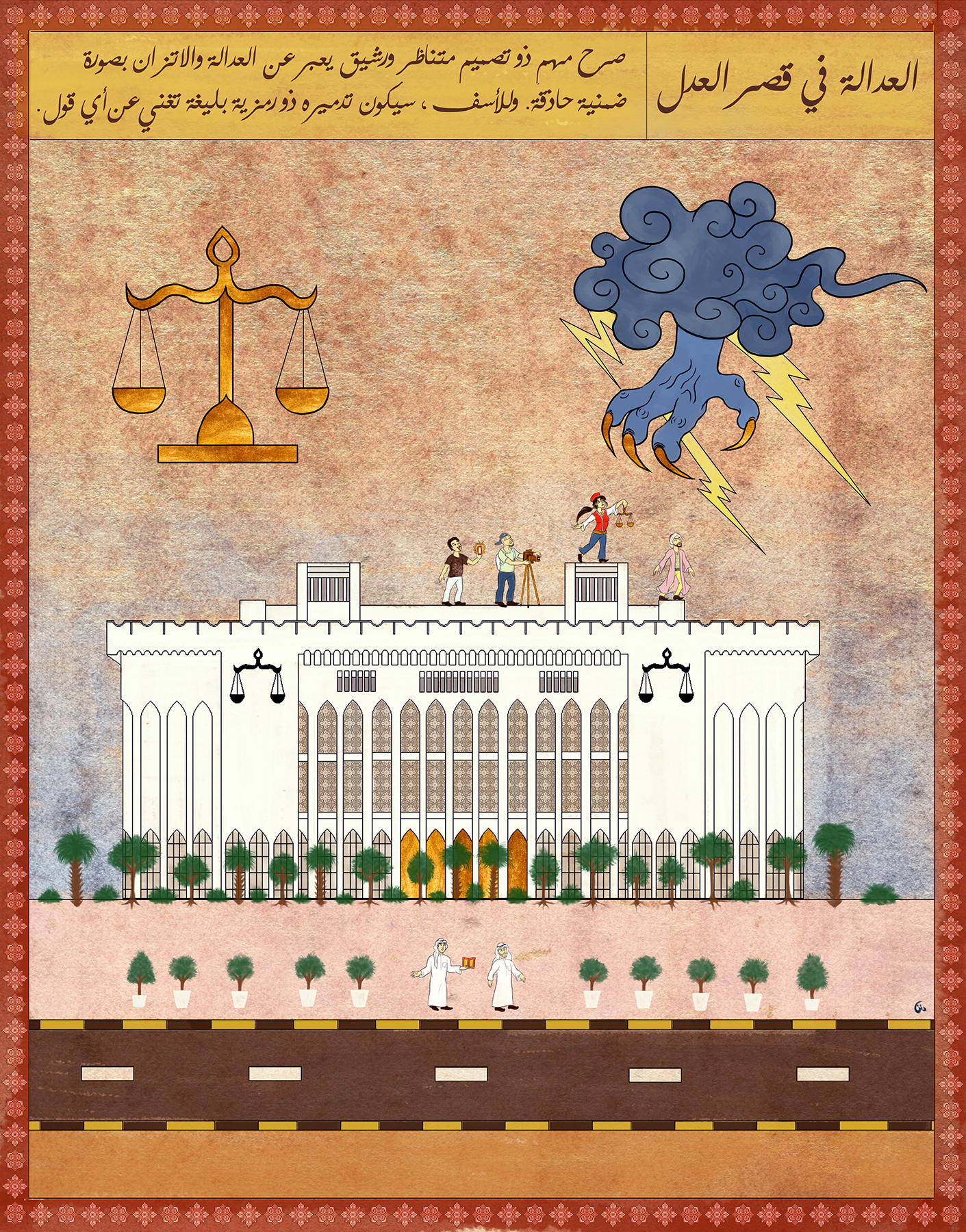

Not all of the houses, buildings, or structures that were built during that time have enjoyed the same protected status of the towers, however, and a number of them have been demolished in more recent years, as the Al Sawaber Complex has been, or are currently under the threat of being demolished. An example of the former is the Ice Skating Rink, which was built in the 1970s as the Middle East’s first ice rink and demolished last year to allow for the third phase of expansion of the Al Shaheed Park; an example of the latter is the mighty 1980s built Justice Palace that is under the threat of being demolished and replaced by a newer glass structure. Digital paintings of both buildings are featured in Architecture of Memory.

Accompanying statements by the artist reflect her frustration — as an architect who specializes in the restoration and preservation of historic buildings — with the recurring demolition of 20th century structures that are not only testaments to the country’s rich modern architectural heritage, but are also an integral part of its collective memory and identity. The Ice Skating Rink, for example, was a site where generations of Kuwaitis spent their leisure time, and which evoked powerful feelings of nostalgia, as is clear from Kuwaiti entrepreneur Laila Al Hamad’s description before its demolition in a 2019 article titled “‘Ice’ plans to tear down our memories”:

“Its place in Kuwait’s memory landscape is ... extraordinary. Beyond any commercial value, the Ice Skating Rink is – par excellence – a pillar of our national heritage; it has shaped the childhood memories of hundreds of thousands of the country’s inhabitants. Ask anyone who grew up in Kuwait in the 1980s what the Ice Skating Rink means to them, and expect a barrage of ecstatic responses. ... I would take my children there to learn to skate as would many of my friends. This generational link gives the ice skating rink a special status; whereas many of the landmarks of our youth – including cinemas and theaters – have been abandoned or demolished, the rink has stood firm in its resilience.”

Al Rashid’s depictions of buildings, monuments, and houses of architectural and sentimental value serve as an important, ongoing form of resistance against their demolition, which is “extremely dangerous because it gradually erodes the collective memory and sense of identity and belonging,” as Al Rashid points out. It also serves as a form of resistance against the forgetting of the structures that have already been destroyed; through her art, they continue to exist in their original, untarnished forms forever.

Though the exhibition may seem Kuwait-centric, its subject matter has greater relevance, and will resonate with those who have experienced the downsides of rapid modernization. Among those are the populations of fellow Arab Gulf cities and states that have undergone a similar historical trajectory as Kuwait’s. Starting in 2019, for example, one of Bahrain’s most well-known hotels, the 1981 built Sheraton Hotel, like its Kuwaiti, Saudi, and Emirati counterparts, underwent an extensive, commercially-driven renovation that transformed it from an iconic modernist hotel to just another contemporary glass structure. The transformation recently led a number of people to express their frustration on Twitter. “If it’s not broken, why fix it? The Sheraton Hotel buildings in both Kuwait and Bahrain were beautiful and reminiscent of a bygone time. Their charm has been completely destroyed by recent renovations,” tweeted Dr. Wafa Alsayed, a Bahraini researcher and postdoctoral fellow at the Gulf University for Science and Technology, while others similarly described it as “ruin[ed],” “soulless,” and entirely unsuited for the island kingdom’s climate. Abu Dhabi’s 1990s-built Al Gurm Corniche also underwent a renovation process during the same time period, through which its iconic fort-inspired light structures and white concrete gazebos were almost entirely removed. Fortunately, a small strip of the old corniche has remained untouched, seemingly as an homage to the original architecture.

“Unfortunately our cities are under attack, not the way people think of, but the fact is that they’re changing so fast,” noted Sheikh Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, an Emirati columnist, researcher, lecturer, architecture enthusiast, and the founder of Barjeel Art Foundation. In a recent interview with France24, he said that “the regulation isn’t [sic] protecting our modern buildings. … The fact is that the speed of development is so high that we can’t keep up and we need to make sure that our modern history is protected. And the reality is that ... when you don’t protect modern history, it makes it easier for people to erase modern history. People can start manipulating the recent past, and the best way to protect it is to preserve it, highlight it, document it, archive it, and share it with the world.” The interview was conducted to discuss and promote Building Sharjah, a newly published book that Al Qassemi edited, that documents and highlights the modern architecture of the UAE’s third biggest city, Sharjah. The book’s synopsis states that in the 1970s, “Sharjah’s potential enticed an international cast of experts to create a bold, new city. As their projects begin to vanish, this book preserves them through unseen photographs and recovered documents.”

Al Qassemi’s book is part of a wave of creative independent efforts in the region to document its disappearing modern architecture, due to the shortage of strong regulations to protect valuable buildings. In addition to using art and literature like Al Rashid and Al Qassemi, some have resorted to documenting modern buildings, houses, and structures through dedicated Instagram accounts. They include Memar Muscat, an Omani youth-driven account that documents the capital city’s modernist architecture, and Architecture Bahrain, an account showcases Bahrain’s ancient and Islamic architecture in addition to its modern architecture. (It is worth noting here that Al Qassemi also initiated an Instagram account that highlights Sharjah’s modern and contemporary architecture in 2016.) Emirati multidisciplinary artist Hussain Al Moosawi is focused on documenting the UAE’s architectural heritage through his photography. Fadhel Almheiri, an Emirati filmmaker, has taken a different approach: He has been animating some of Abu Dhabi’s most famous modern demolished structures. Through his nostalgia and culture-driven upcoming animation film that is cleverly titled Catsaway, he tells the tale of stray cats searching for a new home in a quickly changing Abu Dhabi in 1999, while highlighting the capital’s iconic Volcano Fountain, its once bustling Old Souq, and other important sites.

In the Al Jahiliyya period and the early days of Islam, the use of the motif of Al Wuquf Alaa Al Atlal — or standing on the ruins of a beloved’s previous place of dwelling — was popular among the poets of the Arabian Peninsula. For the heartbroken and devastated poets, the ruins evoked their precious memories and their deep sense of loss. Rapid modernization in the Gulf region today has brought out similar feelings of loss among the generations that were shaped by its disappearing modern architecture, feelings that have been channelled into multidimensional initiatives — their own odes. Though their creative initiatives are valuable and much needed, on the one hand, their increased emergence is worrisome on the other because it highlights a significant issue that could result in the recurrence of scenarios like On the Demolition of Al Sawaber: generations gathering together and watching in helplessness and dismay as structures that shaped their identities and memories disappear in front of their eyes.

You can visit Architecture of Memory until March 31, 2022 at www.khaleejiartmuseum.com.

Sharifah Alhinai is the founder of Khaleeji Art Museum, where she serves as the director, and the founder of Sekka Magazine, where she serves as the managing editor. She is a graduate of the University of Oxford and the School of Oriental and African Studies, and is the recipient of the Arab Woman Award 2020. She tweets at @sharifahalhinai. The opinions expressed in this piece are her own.

Photo by George Steinmetz/Contributor/via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.