In recent years, Omani literature has been taking the world stage and garnering nominations and prizes around the globe. In 2019, Omani author Jokha Alharthi won the Man Booker International Prize for Celestial Bodies, jointly with its translator Marilyn Booth. When explaining why they chose to award them the prize, the judges stated that the novel is “a richly imagined, engaging, and poetic insight into a society in transition.” Similarly, when the French translation of Celestial Bodies won the 2021 Prize for Arab Literature granted by the Institute of the Arab World in Paris last November, the judges described it as a “captivating and poetic novel that allows us to discover an Omani society in full transformation, as well as the living conditions and aspirations of its population.”

What is clear from both statements is that the work, though historical fiction and not an ethnographic text as Alharthi herself has pointed out, provides a window into Oman, a country that remains cloaked in mystery after being closed off to the world for significant parts of the 20th century. Celestial Bodies, which narrates the story of three sisters as they experience love and loss, is more than just a multigenerational story of a family from the fictional village of al-Awafi in Oman in the 20th century; it also traces the complexities of Oman’s transformation from a traditional to a modern society. Through the eyes of a diverse array of characters, the novel sheds light upon obscure chapters from the country’s history, including slavery and war. But these chapters have not just been widely unknown, forgotten, or at least largely undocumented, to those outside the Arab world, but also for those within it, including in Oman itself. As an article by The New York Times accurately notes, “Jokha Alharthi inhabits this liminal space between memory and forgetting: the dark tension between the stories we tell and the stories we know.”

What is also unknown to those who are unfamiliar with Omani literature is that Alharthi’s work is a part of a wide collection of Omani novels that have likewise been inspired by the country’s history, as well as its oral tradition. In fact, Oman’s first novel, Malaikat al-Jabal al-Akhdar by Abdullah Mohammed al-Taie (1965), revolved around the historic al-Jabal al-Akhdar War, a conflict that took place in Oman’s interior region in the 1950s. This pattern of literary works revolving around Oman’s history has continued over time, with Omani novels in both English and Arabic drawing on the country’s long history or centuries-old oral tradition. A more recent example is the 2021 historical fiction novel Dilshad by Omani author and poet Bushra Khalfan. Her nearly 500-page Arabic novel, which is longlisted for this year’s International Prize for Arabic Fiction, tells the story of one family over three generations as it confronts hunger, illness, and desperation in the early to mid-20th century in Oman, a time of hardship in the country’s history.

The novel is not Khalfan’s first work of historical fiction. Five years prior to publishing Dilshad, she had published al-Bagh, which is set in the mid-20th century and encompasses the al-Jabal al-Akhdar War and the Dhofar Rebellion in the 1960s and 1970s. What inspires Khalfan and her counterparts to continually revisit Oman’s history? “Simply because I love reading historical novels, and because history contains chapters that have been dimmed that one should look into,” Khalfan told us. “History is elusive to me.” Both of Khalfan’s novels have received regional acclaim and interest. Dilshad, for example, has been eye-opening for many who lacked prior knowledge about Oman’s economic hardship during the first half of the 20th century. One reader, award-winning Kuwaiti author Saud al-Sanousi, said that Dilshad was as “magnificent as Oman itself.” When asked about the reason for the wide interest in Omani literature, particularly works of historical fiction, Khalfan said, “Omani history is cloaked with mystery, and that makes people curious about it.”

Huda Hamed, an award-winning Omani writer who has written five short story collections and four novels, stated, “Novels that touch upon history — whether they are faithful to it or derive inspiration from it — seem to enjoy popularity particularly when they revolve around the histories of countries that have long been absent [from the scene]; histories that have not been written about before.” She added, “The novels become objects of curiosity and intrigue because they form raw materials about places that have been isolated for a long time. In another respect, novelists have found, in this area, virgin territory for writing.” One of her most noteworthy works is Allati Ta’ud al-Salalim, a novel published in 2014 that touches upon Oman’s rule over parts of East Africa, which began in the 17th century and formally ended in 1964. Allati Ta’ud al-Salalim has been described as a novel that “uncovers Oman’s neglected history and sheds a light on forgotten stories.” But Hamed is not adamant about always exploring history through her literary works. “I am not a writer who considers writing history her mission. I believe that a novelist is not a historian. On the other hand, however, I love when history is presented in a new literary context that produces rich depictions through the eyes of its characters and its intriguing details,” Hamed said. “In my novel, history was not present as it has been recorded in history books. Instead, I chased after the personal histories of Omanis who were present in East Africa before the 1964 coup. I made it my mission to meet people who had lived there and paid attention to the intricate details of their stories. I wanted to capture their personal experiences of living there, whether they were born there or were driven to migrate there because of life’s tough circumstances. Their stories and memories were as inflamed as wounds and as rich as songs.”

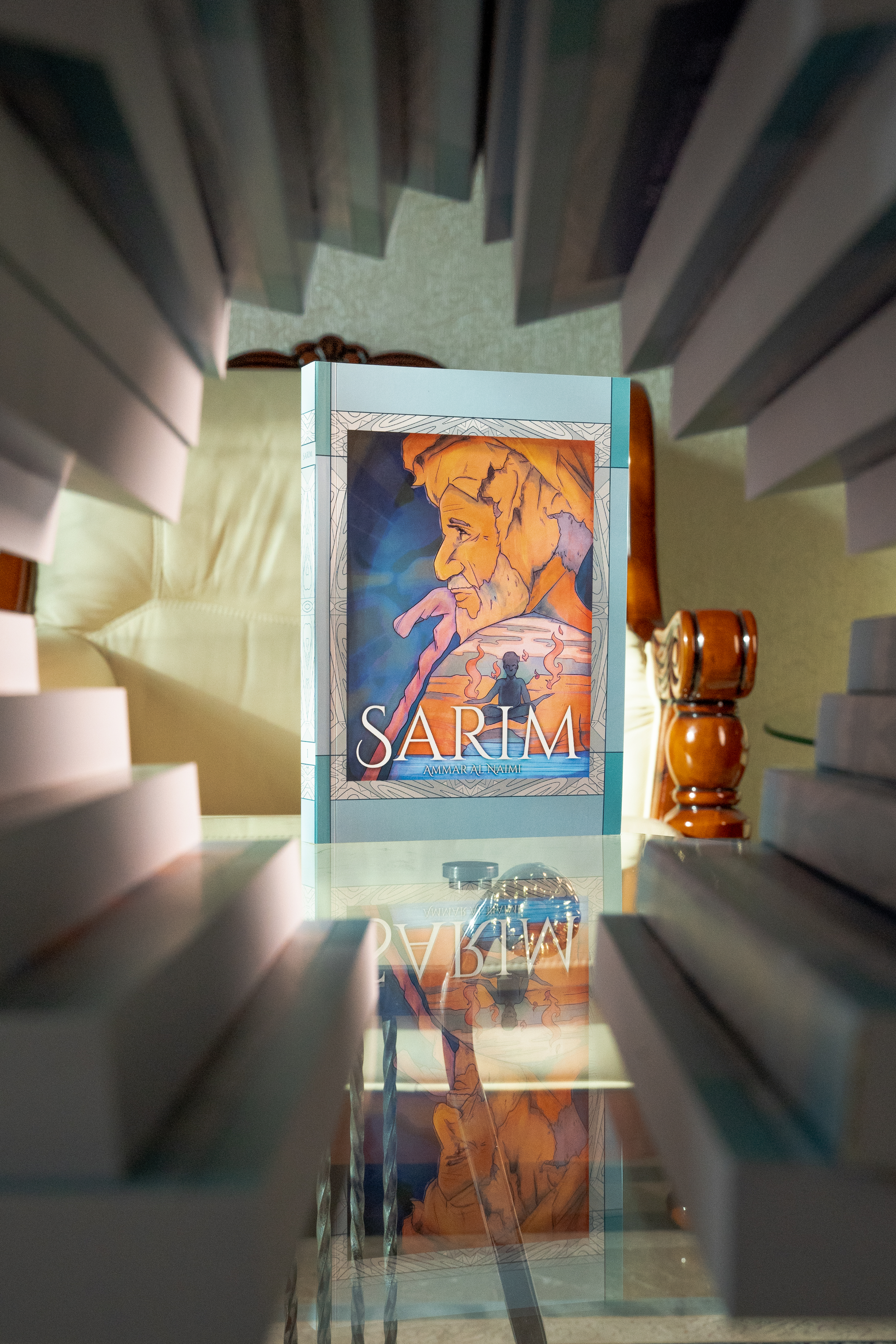

Today, eight years after publishing Allati Ta’ud al-Salalim, Hamed’s focus is on a different aspect of Oman’s history. “What draws me most right now is the history of mythological folktales, which has not yet been made public,” she says. Folktales, many with supernatural elements, have been an integral part of Oman’s culture for centuries, and have been interwoven with its history. In fact, it is not uncommon for narratives about the history of old forts in Oman, for example, to involve the recounting of a supernatural story that is specific to the structure or the surrounding area. One Omani author, 28-year-old Ammar Alnaaimi, channeled his fascination with the local folktales that he had heard from his grandfather into two literary works: Unoriginal Tales: Ten Fantastical Stories from Oman (2019) and Sarim (2021). The former is a collection of fantastical short stories, many of which are set in Oman, while the latter is a novel about the contemporary adventures of an Omani exorcist who wards off djinn. “I like to write fantasy with an Omani twist,” explained Alnaaimi. “My method in using Omani history and folklore relies on the concept of 'Listen, Adapt, Add.’ ... For example, we are told that … if you drive by a wadi [valley] at night and are stopped by a hitchhiker, then you may discover that he has the feet of a goat, and that there was once a duel between a magician father and sorcerer son, which ended with the son being buried alive inside a boulder while the father lamented his failed upbringing. I continue to listen to these stories whenever I have a chance in the hopes of including them in my novels. I also try to make up my own stories in the hopes of adding to the ambiguous richness of Omani folktales.”

But like Alharthi, Khalfan, and Hamed, Alnaaimi does not wish for his work, or the work of fellow fiction writers, to be read as a true representation of Oman’s history or folklore. “On some level, it feels like authors should have the responsibility of formally putting our historical canon into our fictional one, as a way of enriching our tellings and to raise awareness about our history. On the other hand, history and accurate folklore are titanic responsibilities for any writer to shoulder. … We are more than what any single person could represent,” he said. “Let us not rely on every author to represent our countries accurately and in a way we agree with. Let us afford our writers the space to focus instead on creating engaging books that each contain a sliver of who we are. Once there are enough books out in the world, they will come together to create a rich, colorful mosaic of our history and folklore.”

With the relative ease of getting published in the Middle East today and translated beyond the region, Omani writers have made their works accessible to readers around the world, who, after Alharthi’s success, became more interested in Omani literature. “There is a staggering increase in the number of published authors now, as getting published has become an easy process, and a lot of people can pay to get published,” said Hamed. “But is this something good or bad? There’s no definitive answer.” Khalfan has faith that, in the sea of published works, “A good book will always find its way.” She added that, “There’s no harm in working towards establishing a presence in international domains, whether through translation or through participating in serious and respected international events” to increase Oman’s literary presence. In 2021, three Omani authors, Badria Alshihi, Younis al- Akhzami, and Haitham Hussein, had their novels published in English. These translations not only reflect continued interest in Omani literature internationally, but also the continued building of a literary “mosaic,” as Alnaaimi has described, of Oman.

Manar Alhinai is an award-winning journalist, author, and brand storyteller. She is the founder and storyteller-in-chief of Sekka Magazine and the founder and director of the Khaleeji Art Museum. Alhinai is the recipient of the Arab Woman Award 2011 and 2020. She tweets at @manar_alhinai.

Sharifah Alhinai is the founder of Khaleeji Art Museum, where she serves as the director, and the founder of Sekka Magazine, where she serves as the managing editor. She is a graduate of the University of Oxford and the School of Oriental and African Studies, and is the recipient of the Arab Woman Award 2020. She tweets at @sharifahalhinai. The views expressed in this piece are their own.

Top photo: Young Omani author Ammar Alnaaimi. Image by Muhanna Al Siyabi.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.