The Russo-Ukrainian war may be taking place thousands of kilometers away from the Arabian Peninsula, but its impact on energy flows from the Gulf states is far from insignificant. Nearly three years on, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has reshaped trade and investment in the energy sector, leading to an increase in Gulf imports of Russian oil and a sharp rise in the region’s hydrocarbon exports to Europe as well as further fueling the growth of Gulf investment in renewable energy projects located in and targeting the continent.

Imports of Russian oil by Arab Gulf states

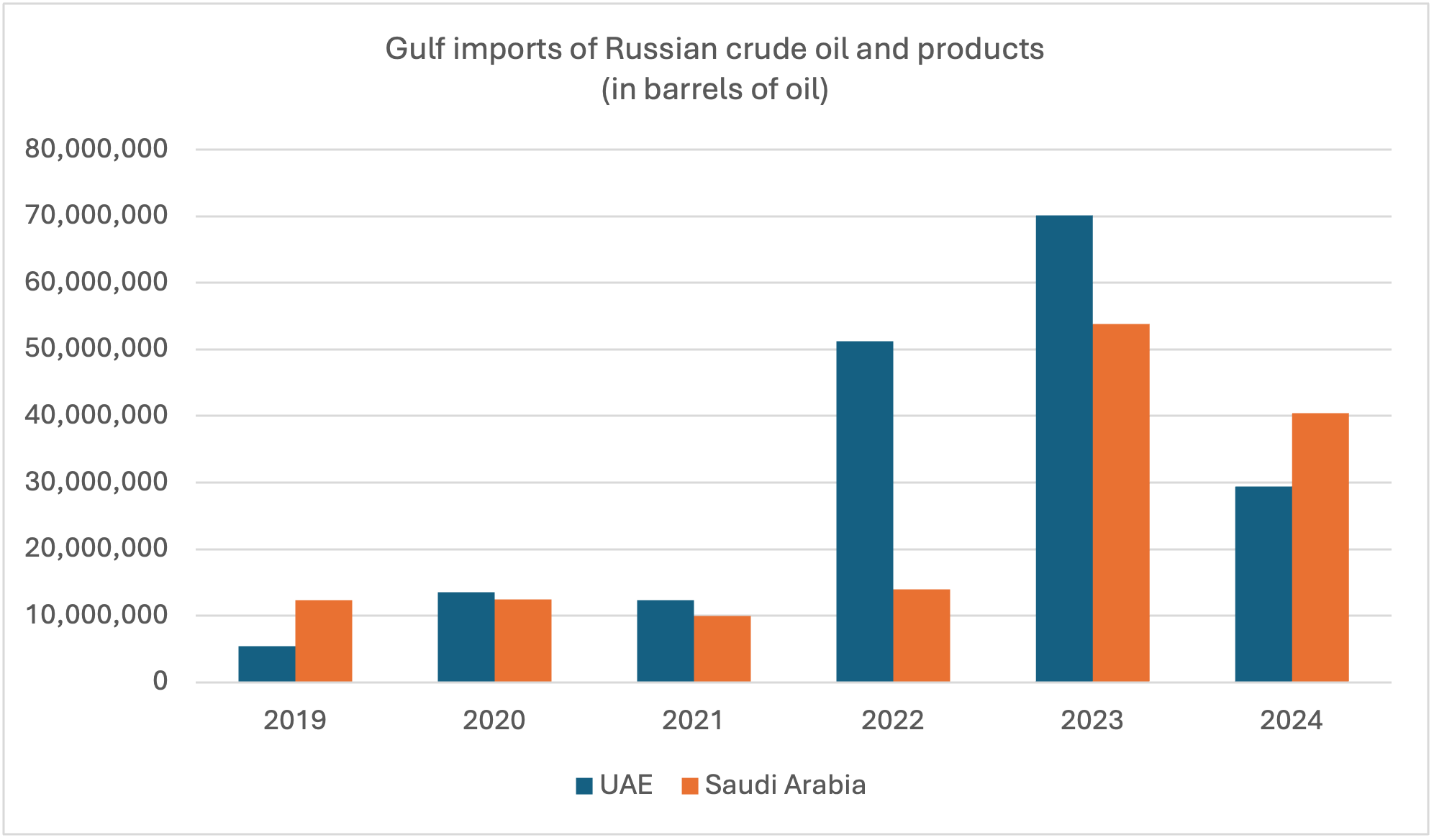

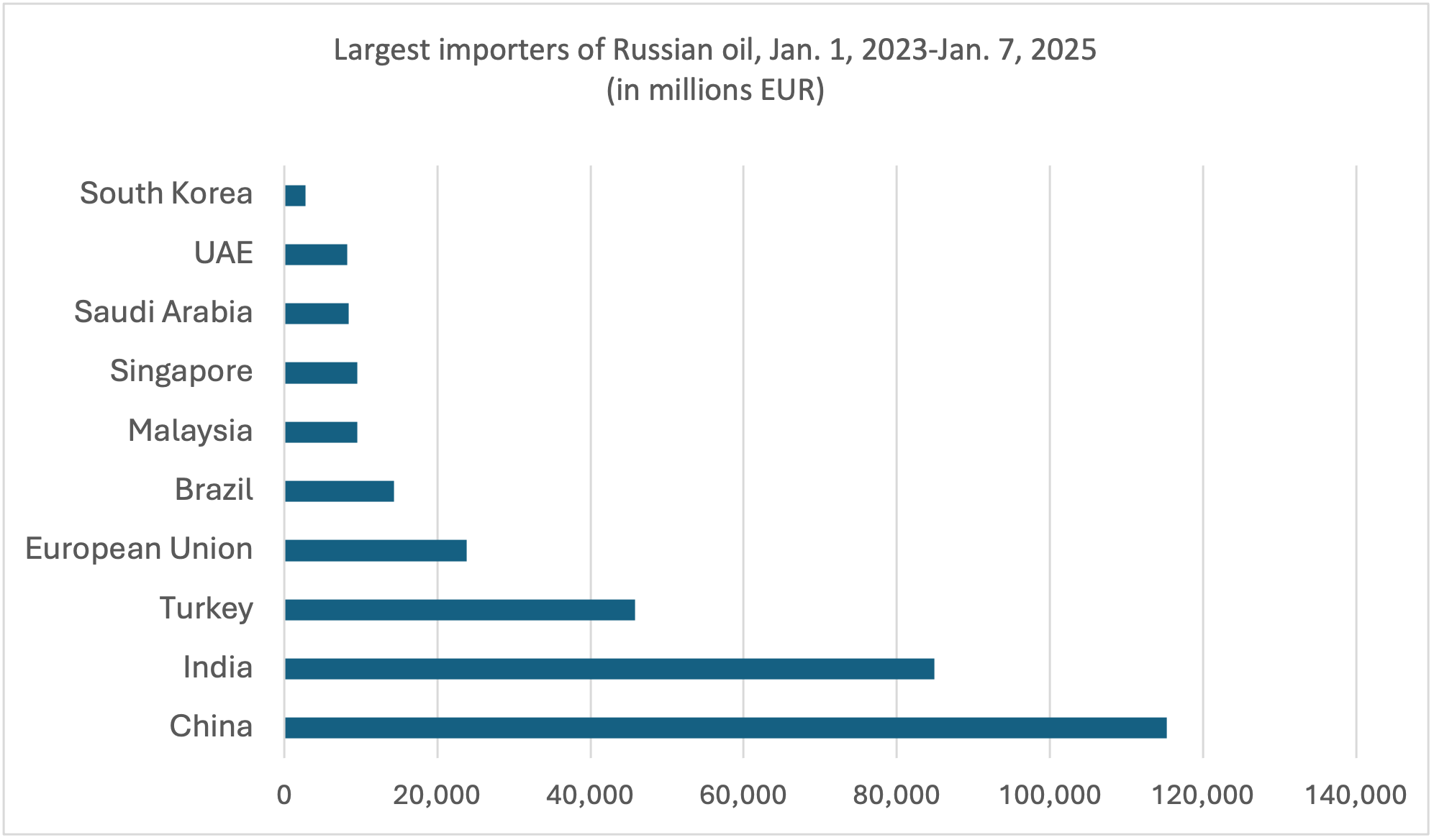

In 2021, Russia was the source of 25% of the crude oil and 40% of the diesel imported by the countries of the European Union. Today, heavily discounted Russian oil, now locked out of its traditional market in Europe, has found its way to the Gulf, where countries have not imposed sanctions on it. Figure 1 highlights the substantial increase in imports of Russian oil, mostly in the form of fuel oil, by the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. While imports in 2024 declined compared to the previous two years, they were still higher relative to 2019. Consequently, these two states now rank among the top 10 largest importers of oil from Russia (Figure 2). While small in absolute terms, particularly compared to China and India, their oil imports account for over €16.9 billion worth of fossil-fuel revenues accrued to Russia as of early February 2025, helping to fund the war effort.

Figure 1

On the one hand, imports of Russian oil by Saudi Arabia and the UAE may be thought of as side payments to Russia to incentivize Moscow’s continued participation in the Organization of Oil Exporting Countries Plus (OPEC+), which is seen as vital to manage oil supply and hence prices, particularly in the face of expected higher oil production by non-OPEC+ members like the United States, Canada, and Brazil. On the other hand, this rise in import volumes is probably largely motivated by arbitrage, whereby countries substitute cheap Russian fuel oil for domestically produced oil used in power plants to generate electricity, or for use by ships as bunker fuel, thereby freeing up more domestic oil for export. In the Gulf, the practice of directly burning crude oil in power plants is mostly limited to Saudi Arabia, where oil accounted for 38% of power generated in 2023. According to statistics from Saudi customs, imports of mineral oil from Russia, a category that includes crude oil and fuel oil, increased 18-fold between 2022 (230.7 million Saudi riyals) and 2023 (4.38 billion Saudi riyals).

Figure 2

Cheaper imported fuel oil from Russia is also very likely being relabeled and used as bunker fuel for ships that call at the ports of Fujairah, the Middle East’s busiest port for bunkering, and Khor Fakkan in the UAE — a move that could boost profit margins. Ship tracking data from Refinitiv, Kpler, and Vortexa (Figure 1) indicate that Russian oil is being delivered there. By contrast, and despite earlier acknowledgements, representatives of storage operators now maintain that no cargoes bearing a Russian certificate of origin have entered the two ports. Given that Iranian oil is routinely sold as “Malaysian” in the case of China, it is not inconceivable that something similar is happening with Russian oil.

Exports of Gulf oil and LNG to Europe

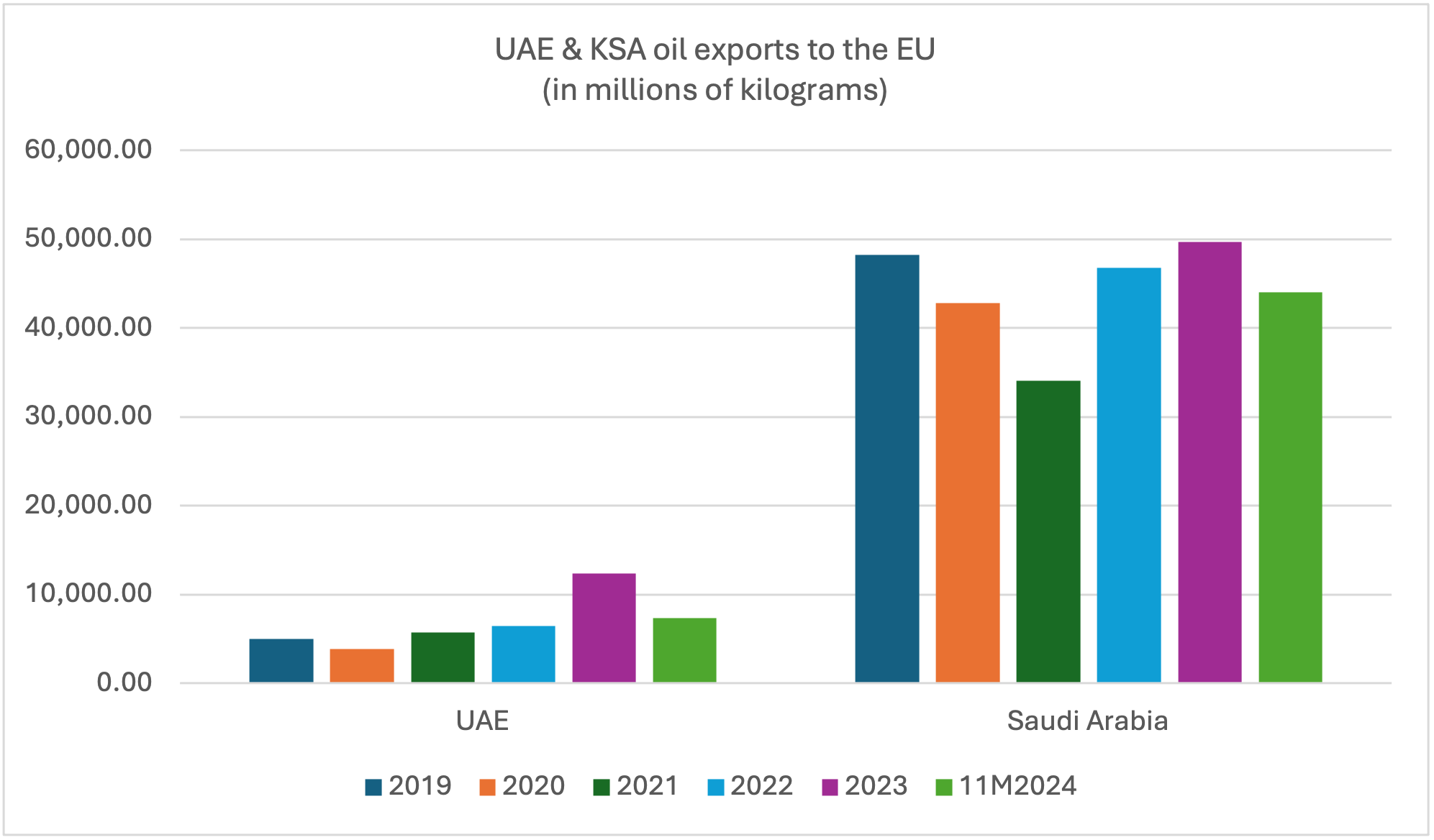

A second effect of the Russo-Ukrainian war relates to changes to hydrocarbon exports to Europe. The similarity of Gulf crude, particularly Saudi Aramco’s Arab Light, to Russia’s Urals crude makes the former a good substitute for the latter. Gulf oil exporters are also likely to have profited from blending imported Russian oil for re-export, including to Europe. This practice has been facilitated by a loophole in EU legislation that allows oil products exported from refineries fed by Russian crude to bypass EU sanctions because the crude is deemed to have been “substantially transformed” through the refining process. For example, one report noted that during the first nine months of 2024 nearly 40% of the EU’s oil product imports from India, China, and Turkey were processed from Russian-origin crude.

Whether or not Russian-origin oil has been blended with Gulf oil, Gulf exports to Europe have increased significantly since the beginning of the war, as highlighted in Figure 3, as the latter sought out alternatives to make up for the shortfall from its long-time supplier Russia. Going forward, Gulf oil exports to Europe may be constrained by the latter’s purchase of more US oil (and gas) in an attempt to head off tariffs; in the longer term, the lower carbon intensity of Gulf fossil fuels should be advantageous.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that decisions by the Gulf states to invest in the creation, expansion, and upgrade of their downstream facilities at al-Zour (Kuwait), Ruwais (Abu Dhabi), and Duqm (Oman) were taken years before the outbreak of the war. Abu Dhabi’s national oil company (ADNOC), for instance, began the process of upgrading Ruwais in 2018 to process lower-quality crude in order to free up premium-quality crude for export, which fetches higher prices in global markets. Consequently, the market shifts sparked by the Russo-Ukrainian war created a timely and opportune new outlet in Europe for high-value oil products from the Gulf.

Figure 3

The Russo-Ukrainian war is also facilitating a broadening of the Gulf’s client base for liquefied natural gas (LNG) to include more European customers. Hitherto, Gulf LNG exporters like the UAE, Oman, and Qatar were focused on Asia due to Russia’s stranglehold on pipeline gas exports to Europe and the higher premiums commanded by LNG in northeast Asia. Russia’s determination to weaponize Europe’s gas dependency opened the door for the Gulf to supply greater spot volumes to Europe as well as to sign much coveted long-term contracts (Table 1). The current harsh winter in Europe relative to the previous two years (and compared to the mild winter in northeast Asia) and the need to replenish storage ahead of next winter augur well for increased LNG imports by Europe, including from the Gulf states.

Table 1: Long-term LNG contracts concluded between Gulf exporters and Europe after February 2022

Renewable energy flows to Europe

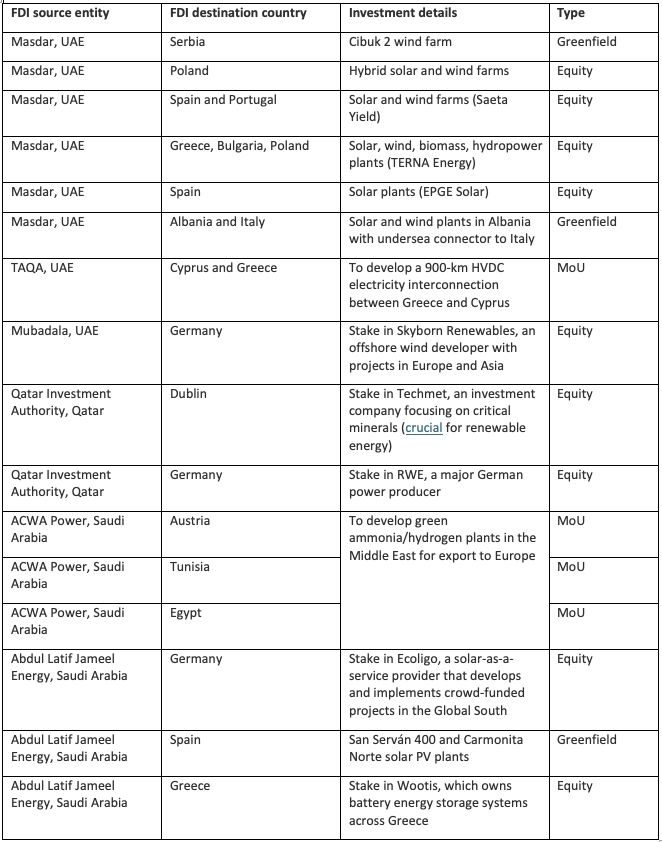

The Russo-Ukrainian war is occurring alongside a significant increase in Gulf investments in renewable energy projects both within and targeted at Europe (Table 2). Abu Dhabi’s Masdar, for instance, had greenfield and equity investments in wind farms in Serbia, Montenegro, and Poland prior to the war. Since the war, however, its solar and wind equity portfolio has expanded to include power plants in Greece, Spain, and Portugal, together with additional assets in Serbia and Poland. Although Masdar leads its Gulf peers in terms of new investments concluded since the start of the war, Qatar — through Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) and Nebras Power — had previously built up a sizeable portfolio of investments in the European renewable power sector, including assets in Ukraine. The Gulf states’ participation in boosting Europe’s renewable power capacity is in line with the bloc’s REPowerEU plan, which aims to increase the contribution of renewables to Europe’s energy mix to 42.5% (or 72% of its electricity) by 2030, up from 22% (or 37% of electricity) in 2021. This would enhance energy self-sufficiency while reducing reliance on fossil fuels and Russian energy in particular.

Table 2: Examples of Gulf investments in Europe’s clean power sector post-February 2022

Nevertheless, it is important to note that the interest of the Gulf states in Europe’s green power market predates the war and is being driven by their own economic diversification goals. For example, in January 2020, QIA announced it would no longer make new investments in fossil fuels. In January 2022, Masdar set out a target of expanding its renewable energy capacity from 20 gigawatts (GW) to 100 GW by 2030. Cognizant that much of the capacity growth is from greenfield projects in developing countries that are below investment grade, such as Uzbekistan, Masdar and ACWA Power are expanding their presence in developed markets like Europe and the US to balance their portfolios.

Sustainability of changes in energy flows

The extent to which these three trends are sustainable over the medium or longer terms is consequential for decision makers in both the policy and business worlds. First, imports of Russian oil by the Gulf states are unlikely to reach new highs partly due to current and expected US sanctions under Donald Trump's administration. These will likely limit the availability of vessels that can be used to transport Russian oil and may threaten secondary sanctions on buyers. Customers in China and India have already scaled back purchases of Russian oil, and ports in the UAE may do the same due to concerns about reputational and operational risks. A decline in imports by Saudi Arabia can also be expected as more renewable power plants come on-line as part of the kingdom’s strategy of reaching a power mix in 2030 whereby renewables account for 50% of generation capacity, thereby displacing Russian fuel oil imports used to meet peak summer demand. This reduction in Russian oil imports has a low probability of negatively impacting the wider Russia-Gulf relationship given the importance that both sides place on the OPEC+ platform to manage oil supply (and hence prices), on diversification of partners, and on cooperation on regional issues such as terrorism, Syria, and Libya.

Second, while exports of Gulf oil and gas to Europe are likely to continue, it is highly improbable that Europe will overtake Asia as the main destination for the region’s hydrocarbons. On the one hand, limited volumes of Russian gas may return to Europe on the back of a peace deal to end the war, thanks to legacy infrastructure and cost efficiencies, but Europe is highly unlikely to return to its previous dependence on Russian energy. On the other hand, the Gulf states understand that Asia’s demographics, consumption patterns, commitments to alter the domestic energy mix, and the comparative advantage of Gulf-Asia trade are key to the sustainability of their hydrocarbon industry and revenues. For instance, 75% of Saudi crude exports went to Asia in 2023, along with 82% of Qatari LNG. In contrast, Europe’s fossil fuel consumption has probably peaked, while its commitment to a low-carbon energy system remains strong.

Third, the Gulf states will likely try to continue to capitalize on Europe’s focus on renewable energy. This will not be limited to investments in its power sector but is also likely to include efforts to boost market penetration for low-carbon steel, aluminum, and fertilizers, which are in demand in Europe and for which Gulf companies have world-class competencies. Progress on concluding the long-stalled EU-Gulf Cooperation Council free trade agreement would, therefore, be helpful. At the same time, renewable power opportunities in Asia should not be overlooked.

Li-Chen Sim is an Assistant Professor at Khalifa University (UAE) and a non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute (USA).

Photo by AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.