The Caspian Sea, the world’s largest inland body of water, is steadily shrinking. Water levels reached a critical low in 2022 and continue to fall by 6-7 centimeters per year, with some projections suggesting it could drop by as much as 9-18 meters by the end of the century. Although the five littoral states — Iran, Azerbaijan, Russia, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan — have a history of making efforts to maintain it, the unique environment of the Caspian basin has been in decline in recent years.

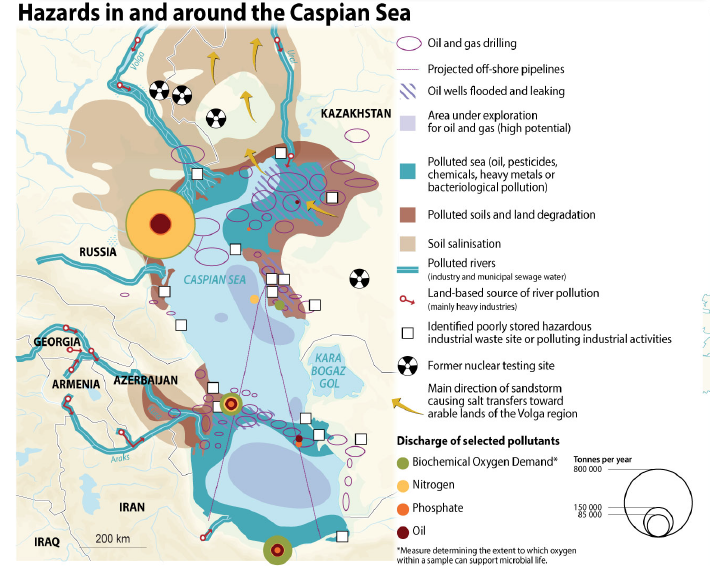

As the largest natural asset shared by Iran and Russia, the Caspian Sea continues to play a significant role in their relations and is central to the region’s prosperity. The lack of a solid legal framework surrounding the management of the sea among the littoral states, and particularly by Iran and Russia as the most powerful ones, has created a degree of ambivalence about where and how to limit ambitions related to oil, gas, fishing, and other environmentally harmful economic activities. Combined with rising air temperatures and decreased annual precipitation in the region, if the respective impacts of Iranian and Russian industry are not appropriately addressed, the consequences for the Caspian Sea, the horizon of which is peppered with oil and gas rigs and fishing vessels, could be irreversible.

Facing international isolation and severe economic sanctions, Iran and Russia have moved to strengthen their relations over the past year, a process that has been nothing short of tumultuous. Although the two nations have experienced frequent tensions, raising questions about the drivers and limits of their relationship, efforts to address shared environmental problems and maintain the Caspian Sea could serve as an area for mutually beneficial cooperation, with a positive impact for other littoral states.

The physical, economic, and human impact of environmental damage

As it shrinks, the Caspian Sea is also eutrophying at an alarming rate, with high levels of chlorophyll-a contributing to harmful algal blooms, mainly in the northwest toward the Russian Volga River delta. Eutrophication occurs when coastal waters or estuaries become overly enriched with nutrients, often from surrounding agricultural activity, and consequently spur excessive plant and algae growth. This process, at its height, results in ocean acidification, which kills fish, harms mollusk populations, and reduces underwater habitats.

If this deterioration continues, it will also further inhibit the Caspian’s critical sturgeon-fishing industry and lead to more severe stock declines. In the 1990s, there was a sharp decline in sturgeon stocks “due to ecological changes caused by human activities” as reported by the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, dropping from 28,126 million tons in 1980 to 3,872 million tons in 1997. By 2011, the fishing of sturgeon was banned entirely by the Interdepartmental Commission on Aquatic Bioresources of the Caspian Sea, wiping out the high-value industry. This ban has been renewed on an annual basis ever since.

The mismanagement of the sea and subsequent fishing restrictions have already caused widespread negative economic consequences to the detriment of the cities bordering the Caspian in both Russia and Iran, including along the densely populated Iranian southern coast, where “one agglomeration leads into the next.” A heavy burden is placed on fishermen in the littoral states, who for generations had depended on the plentiful sturgeon for their livelihood. Fishermen in the Mazandaran region of Iran, for example, had made around 1 million tomans ($359) in 2014, with this dropping to 500,000 ($179) just one year later because, as they said, “There are no fish in the sea.”

In addition to the economic impact, the degradation of coastal areas also poses major public health risks for all those who use the body of water for commercial and recreational purposes. Based on a study from 2022, it was estimated that current levels of heavy metal contamination create an up to 6% cancer risk for adults. This risk rises to up to 18% in the case of swimmers undergoing long periods of exposure, “indicating the local population is at a higher risk.” Overall, the analysis confirmed that the presence of these anthropogenic sources could lead to cancer. In addition, the Caspian region also faces an increase in cases of asthma, tuberculosis, and rheumatism emerging in rural littoral towns since the changes in sea levels, as well as a rise in invasive snakes and bugs “due to a proliferation of swampy areas formed by receding sea water.”

Environmental degradation and worsening economic impacts can create a vicious circle. In towns such as Gorgan in Iran, studies have shown that “socioeconomic status influenced the social value orientations and responsible behaviours of individuals toward the environment.” Poor socioeconomic conditions are also prevalent in Russia’s bordering towns as well, such as those in the Dagestan region in the North Caucasus. This can serve as evidence that in the future, if the state allows the environment to worsen, civilians in the vicinity will also mistreat their environment. As most occupations in the Caspian basin rely on ecologically harmful activities, it would be up to the state to ensure that other opportunities are found and that environmental restrictions are respected.

Pointing fingers

The Volga River, at 3,700 kilometers, is the longest river in Europe, running from the north of Moscow all the way through to the southeast of Russia, its delta in the Caspian Sea. It has also been identified as one of the main sources of pollution for the Caspian, alongside oil drilling works, as it flows through a number of industrial and agricultural areas, picking up an array of contaminants on its way. According to a study in the scientific journal Coastal Management, these contaminants include “petroleum hydrocarbons, phenols, surfactants, and organochlorine pesticides […] mainly from rivers originating or flowing through Russia.” Additionally, there is ample evidence suggesting that “water flow alteration in the Volga has had a direct impact on the water levels in the [Caspian Sea] and its coastal areas.” Iranian media outlets have also pointed to Russia’s numerous hydroelectric dams on the Volga River, which accounts for nearly 85% of the water flow into the Caspian Sea, noting that, “Russia has built 40 dams and 18 more dams are under construction,” reducing the flow of water into the sea.

Along the same lines, Ali Salajegheh, the head of the Iranian Department of Environment, recently asserted that the closure of vital entrances to the Caspian Sea, such as the Volga River, is to blame for “a significant decrease in the sea's water levels, which poses a serious ecological challenge.” Salajegheh blamed Russia for the rapid decline and urgently warned of “alarming statistics,” claiming that the sea has experienced “a reduction of approximately one meter over the last 4-5 years,” though without making any reference to the impact of climate change or the recent extreme temperatures across the region. Iranian media outlet Iran International called it an “unusual attack” from Salajegheh, given the recent closeness Tehran and Moscow have demonstrated in their alliance following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

While blaming Russia for the Caspian Sea’s ills might appear to be part of a political agenda, this is seemingly an earnest attempt at raising an alarm. The Iranian UNESCO-affiliated environmentalist Mohammad Darvish has also noted that, “It is not clear how much the Caspian annually needs from Kazakhstan, Iran, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Russia,” and Iran itself has also “built dozens of dams and established large industries on Atrak, Gorgan, Sefid-Rud and all the rivers that flow towards the Caspian.” His remarks prompted the Iranian newspaper, Shargh, to warn that, “If we cannot come to terms with Russia on this issue, everyone's work is over, even Russia itself.”

Current cooperation and areas for future collaboration

The current state of cooperation between Iran and Russia on these issues is difficult to gauge due to the lack of a concrete multilateral agreement on managing the Caspian Sea, though some noteworthy efforts have been made. In the past, the Caspian Environment Program and its United Nations partners sparked several initiatives aimed at protecting the sea with the “goal of assisting transboundary diagnostic analysis.” In 2006, the region also saw the ratification of the Tehran Convention, which aims to serve as “an overarching legal instrument laying down general requirements and the institutional mechanism for environmental protection in the Caspian Sea region.” Its two major ambitions are: (i) prevention, reduction, and control of pollution; and (ii) protection, preservation, and restoration of the marine environment. At present, efforts under the convention are focused on ecological preservation studies and projects, attempts at engaging civil society, and enhancing its strategy for monitoring the Caspian environment.

While Salajegheh expressed a desire to resolve many of the current disputes through the Tehran Convention, a recent development has given the prospects for collaboration between Russia and Iran a significant boost. On Aug. 19, Igor Shumakov, the head of Russia’s Federal Service for Hydrometeorology and Environmental Monitoring, made it clear that Moscow is willing to work with Tehran to monitor the Caspian Sea’s decreasing water levels. Speaking to the Islamic Republic News Agency, Shumakov claimed that the drop in water levels is a temporary development that will last for only a decade or two, but added that Russian experts are closely monitoring the situation.

While there has clearly been an interest in collaborating to preserve the marine environment of the Caspian over the nearly two decades since the Tehran Convention was adopted, the sea still faces a significant risk of environmental disaster. Even with the convention in place, sufficient efforts have not been made to address these issues, which is why a reinvigoration of Iranian-Russian partnership on this front is critical. Moscow and Tehran have an opportunity to work together to address the myriad interlinked challenges facing the Caspian region. There is much the two countries can do, including agreeing on procedures in the event of accidents or emergencies, such as oil spills or other pollution.

Outlook

The ambiguities in the agreed legal treatment and consideration of the Caspian Sea is a major contributor to its environmental collapse. This lack of consensus has given rise to legal disputes among the littoral states about their rights, with unclear clauses and loopholes that have been exploited, particularly when it comes to oil and gas production. Unless and until these issues can be addressed by establishing a mutually agreed upon legal framework among the littoral states, the “competitive use” of the Caspian’s abundant hydrocarbon resources is only likely to exacerbate environmental problems and “create additional water quality-related challenges in the future.”

As experts have warned, individual policies in the Caspian basin can only take the littoral states so far, and it is evident that collaboration is the most efficient and effective route toward shared prosperity in the long term. It is already a sign of progress that Moscow and Tehran seem to be willing to collaborate; the next step will be to see if they can follow through on their promises.

Henna Moussavi is an MPhil candidate in Modern Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Oxford. She is also the Editor-in-chief of the Oxford Middle East Review. Her research regards contemporary Iranian political and social affairs.

Photo by Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.