Late last month, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei opted to replace the secretary of the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), Ali Shamkhani. The latter’s removal after 10 years spent in this key role has generated much speculation, misinformation, and outright disinformation. Some accounts see President Ebrahim Raisi as the one who lobbied for Shamkhani’s removal, as the SNSC head was grabbing too much attention at the expense of the president’s team. Other explanations point to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as the culprit. While both Shamkhani and his replacement, Ali Akbar Ahmadian, come from the ranks of the IRGC, the successor better reflects the present-day hardline stance of the Guards.

Other mentioned rationales for Shamkhani’s sudden departure include his family’s alleged role in corruption, the arrest and recent execution of one of his associates as a British spy, and him upsetting Khamenei by remaining close to Mohammad Khatami, the torch-bearer of the reformist movement. Meanwhile, two facts are beyond doubt: First, Khamenei had good reasons to want Shamkhani to continue to lead the SNSC even after Raisi took over as president in August 2021; and second, the dirty campaign to unseat Shamkhani speaks volumes about the fierce internal regime struggle to win the succession fight when Khamenei eventually dies.

Why Khamenei kept Shamkhani in the job

Raisi was never expected to be a strong president. Khamenei engineered Raisi’s election because he considers Raisi to be obedient to his wishes as supreme leader. Raisi’s policy record has been fairly dismal since he took office in August 2021. That has been true particularly as far the economy is concerned, a realm where the presidency has historically had the greatest influence inside the institutional framework of the Islamic Republic.

The question that emerged within months of Raisi’s inauguration was whether his weak political standing combined with his poor policy performance on the economy would sideline his government when it came to Tehran’s foreign policy. The answer appears to be “yes,” as a number of other prominent regime figures have been more visible in foreign policy-making during the Raisi presidency. Most notably, Shamkhani took the limelight in negotiating with the Russians, Chinese, and Tehran’s Arab neighbors, including on the March 2023 China-brokered deal to normalize diplomatic relations with Riyadh.

Whether Shamkhani’s role in recent months had been disproportionate is debatable: He was after all the head of the SNSC, the most important decision-making body in the regime. And yet, while Shamkhani occupied the same role when Hassan Rouhani was president (2013-21), it was then mostly Foreign Minister Javad Zarif who took centerstage when it came to foreign affairs. Under the current presidency, there is a widespread impression that Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian is simply a lame duck.

But the relative sidelining of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) is not just in relation to the SNSC. Other regime bodies and figures have also seen their foreign policy profile elevated during President Raisi’s tenure. Take the case of Kamal Kharrazi, an advisor to Khamenei and the head of the Strategic Council on Foreign Relations (SCFR). Kharrazi has consistently been a prominent voice on Iranian foreign policy even after he concluded his term as foreign minister (in 2005); but his activities notably increased when Raisi took over as president, including visiting Bashar al-Assad in Damascus and representing Iran at high-level international gatherings.

Another SCFR member, Abbas Araghchi, who was a top associate of Zarif, also recently reappeared in the news when he warned on national television that a “plot” was being concocted to sideline Iran in the region. He also accompanied Kharrazi to meet Assad.

Another former foreign minister, Ali Akbar Velayati, has made important foreign policy statements on behalf of Tehran under the Raisi government as well. Velayati most famously entered the fray amid Iran’s growing tensions with Azerbaijan earlier this year by directing warnings at Baku about its policies toward Tehran.

When it comes to Velayati’s intervention, as arguably with all other such interventions by individuals from outside Raisi’s administration, the question to ask is not only whether Khamenei trusts the Raisi government to handle a given foreign policy issue but whether it has the necessary diplomatic skillset to achieve the Iranian supreme leader’s desired goals. The centrality of Khamenei here should not be underestimated. For example, the last time Velayati made big headlines was in July 2018, when he visited Moscow to bring Khamenei’s message to Russian President Vladimir Putin. This was shortly after the Trump administration had left the 2015 nuclear deal, and the Iranians wanted to coordinate their response with the Russians. Notably, it was also a period when the purportedly powerful Zarif was still Iran’s top diplomat. But in fact, Rouhani’s second term was more and more frequently punctuated by foreign policy interventions by Khamenei’s office. This was due to the sense of urgency the supreme leader felt about certain foreign policy files, and he opted to just cut out the middle-man — the MFA.

Likewise, the increasing role played by various regime figures and agencies today, such as the SNSC, is arguably not a reflection on the Raisi government per se but an indicator that Khamenei wants to streamline the policy process for speedier results. This was perhaps best illustrated by the way Tehran recently handled the rapprochement with Saudi Arabia. Shamkhani and the SNSC took the lead to negotiate the substance of the deal, whereas Amir-Abdollahian and the MFA were left with the task of implementing the outcome.

Not all analysts are convinced by this interpretation. They argue instead that Khamenei’s motives for intervening in foreign policy in Rouhani’s second term have nothing to do with why he is now limiting the Raisi government’s foreign policy role. For example, in sending Velayati to Russia in 2018, Khamenei did so not because he was after quick results but because he felt Zarif would be the wrong man to send to Moscow. Zarif is, after all, known as the pro-West voice in the regime, and Moscow is suspicious of him. Whereas, in the case of the Raisi team, the skeptics point out, it is not so much about the wrong person for the job. It is about Khamenei’s fundamental belief that the Raisi government is not cut out to meet the challenges of Iran’s foreign policy due to inexperience and potential incompetence. Khamenei is aware of the criticism floating out there about the present team officially in charge of Iranian foreign policy, and he has publicly responded.

Khamenei’s defense of tight oversight of foreign policy

No one will forget when Qassem Soleimani invited Assad to Tehran in 2019 without telling Foreign Minister Zarif. Zarif’s response, to hand in his resignation, showed the extent of the fight in Tehran over sensitive foreign and regional files.

There were other similar cases as well: In 2021, Khamenei hand-picked former speaker of the parliament Ali Larijani as his special envoy to China. He sent parliamentary speaker Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf to Moscow, but that turned out to be a flop. Putin refused to meet Qalibaf — who was also at the time a presidential candidate and looking to raise his profile — because his trip had not been properly arranged by Tehran, illustrating how fast-tracking foreign policy can backfire. Yet Khamenei remains relentless.

As Khamenei put it in May 2021, “nowhere in the world is foreign policy decided by the foreign ministry.” This comment was in response to Zarif’s criticism that his MFA was constantly being undermined by the actions of other organs in the regime. Zarif, whose sharp criticism had been leaked to the media, was specifically angry about the expansive role that the IRGC plays in setting the agenda for Tehran’s regional policies.

Doubts about the diminishing role of the MFA have not subsided since then, even though Zarif’s successor, Foreign Minister Amir-Abdollahian, comes from a background in the IRGC. It had little to do with questions of Amir-Abdollahian’s loyalty and far more to do with concerns about his command of foreign policy.

This perceived lack of command is why Shamkhani took the lead in the most sensitive affairs, notably on the Arab and Russia files. The irony is that Amir-Abdollahian’s biggest area of expertise is supposed to be the Arab world: A trusted ally of Soleimani, he had spent years as Zarif’s deputy for Arab-African affairs at the MFA. When Zarif fired him in 2016, hardliners came to Amir-Abdollahian’s aid.

Zarif was accused of having fired a true “revolutionary diplomat” who spearheaded Tehran’s activities in the Arab world. In fact, Amir-Abdollahian’s firing at the time was depicted by the hardliners in Tehran as a possible “concession” by the Rouhani government to the Americans and Gulf Arabs, who resented Amir-Abdollahian as a representative of the interests of the IRGC. Some commentators went so far as to claim that the firing had been part of an effort by Rouhani and Zarif to offer broader regional concessions to the Americans to make the 2015 nuclear deal more sustainable.

But once he became foreign minister in 2021, Amir-Abdollahian quickly displayed his limitations. In particular, his poor command of Arabic has become a liability for him. Seeking to defend himself, he respond, “Let there be no doubt. There is sufficient policy harmony [inside the regime]. Let the enemies know there is no difference [of opinion on foreign policy].” But domestically, this claim was turned on its head, raising speculation that Amir-Abdollahian was fighting to keep himself relevant in Iran’s foreign policy-making process.

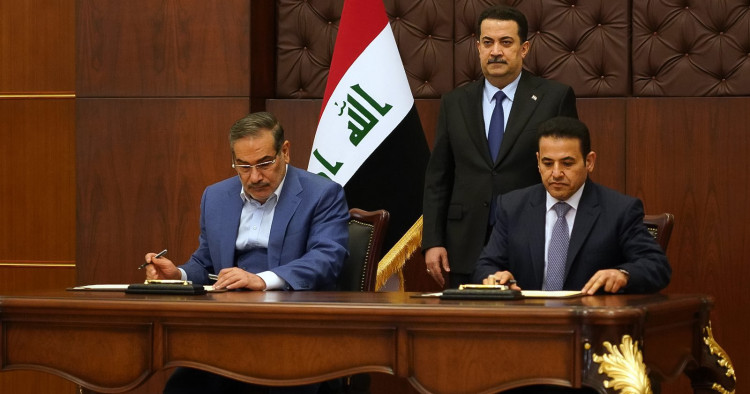

Take the case of Iraq, a country often presumed to be significantly under Tehran’s control, though which might or might not be the case. As far as Iranian perceptions are concerned, the Raisi government has kept a poor handle on this file. The prime example has been Iraq’s refusal to pay back to Iran billions of dollars in outstanding debt, accumulated under U.S. sanctions. As with his handling of the Saudi file, it seems that Shamkhani, who is fluent in Arabic, was subsequently brought in to restore things on Iraq-related matters. He last visited Iraq in March, and his conversations with his hosts focused on “security matters,” but Iran’s economic grievances were also raised. What is known for certain is that Shamkhani, who had a secondary role under the Rouhani presidency, had taken charge of most of the sensitive foreign relationships — and with Khamenei’s approval.

The stance of the Revolutionary Guards

Another question to ask is where the IRGC stands in this shifting balance of power among agencies vying for control of Iran’s foreign and regional policies. For a long time, there was no doubt that Soleimani and his Quds Force managed the regional files. He was Khamenei’s top envoy on regional issues and answered only to the Office of the Supreme Leader. However, with Soleimani’s assassination by U.S. forces during the Trump administration and the subsequent rise of Shamkhani, the significance of the SNSC in setting the agenda was elevated.

According to Iranian sources, the death of Soleimani resulted in a significant loss of Iranian influence in Iraq. Not only has his successor, Esmail Qaani, struggled to fill Soleimani’s big shoes, but the arrival of Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi (May 2021-October 2022) also decreased Tehran’s clout in Baghdad. Because of this loss of Iranian influence in the region after Soleimani’s death, the argument goes, Tehran decided to compromise with Riyadh. And Khamenei gave the job of negotiating with the kingdom to someone he believed the Saudis know well and could work with — Shamkhani.

There are those in Tehran who argue that Shamkhani had relied on diplomatic tools to preserve Iran’s regional interests, whereas Soleimani was a firm believer in hard-power projection through the use of proxies. This is at best only a theory but an important point to unpack. If this argument is true, then one can make a more fundamental deduction: That Khamenei, who controls how much influence Shamkhani had on regional files, had opted for more diplomacy at the expense of the Quds Force. That was exactly what Zarif had urged Khamenei to do, but it took Soleimani’s death before the supreme leader was willing to choose this path.

Again, if this assessment is correct, then it is not the case of one faction in Tehran losing out to another faction on regional policy-making. Rather, Khamenei, likely with the support of the Presidential Palace and the IRGC, is spearheading a regime-wide shift toward more diplomacy and less militarism.

Perhaps Khamenei had come to the conclusion that the regime’s survival required this shift in Iran’s approach to the region and the rest of the world. If so, the central role that Shamkhani played should not be a surprise: Not only was he trusted by Khamenei but he is a long-time member of the IRGC himself and, therefore, someone well-placed to drag the Guards onto this path of regional de-escalation. For sure, the IRGC would not have trusted Zarif in the same way if he had appealed to them for a policy re-think.

And then comes Shamkhani’s sudden fall as head of the SNSC. Why the timing, and is it not counter-intuitive to the idea of regional de-escalation that Khamenei vows a commitment to? Without Khamenei’s lead, the decrease in the role of the Raisi government would not have been possible. Shamkhani and his SNSC did not force their way into becoming the key handlers of Iran’s top foreign files: Khamenei wanted them to play this role.

His motivations are clear. Khamenei has, for now, decided that regional de-escalation best serves the regime. And the best man for the job was initially Shamkhani. Despite the smear campaign against Shamkhani, Khamenei kept him in the role until the deal with Riyadh was made in March.

What came next is still a puzzle. But one interpretation is that perhaps the Raisi government is not as feeble as many had anticipated and was actually able to successfully pressure Khamenei to remove Shamkhani. Or perhaps Khamenei himself chose to sideline Shamkhani. The latter is a relatively big political personality and could become more of an independent political operator if he wanted to do so. Shamkhani has also demonstrated his deep ambitions, as when he ran for the presidency in 2001.

So maybe Khamenei does not think Shamkhani should become a bigger name and political force than he already is, and that is why he agreed to have Shamkhani removed? It is no secret that the 84-year-old Khamenei is busy organizing his succession process. He needed Shamkhani to help defuse some of the toughest regional challenges, such as the costly standoff with the Saudis. But Shamkhani’s potential as a loose cannon in the long run posed a risk to Khamenei’s plans for the political order to come after he dies. And ultimately that’s why Shamkhani had to go. There are many moving parts in this still enigmatic affair, yet the central role played by Khamenei is beyond doubt. If so, the message is clear: Shamkhani’s removal is about an internal power struggle but not an event that heralds a reversal of Iran’s recent foreign policy decisions.

Alex Vatanka is the director of the Iran Program and a senior fellow in the Black Sea Program at the Middle East Institute in Washington. His most recent book is The Battle of the Ayatollahs in Iran: The United States, Foreign Policy, and Political Rivalry Since 1979.

Photo by Iraqi Prime Ministry Press Office/Handout/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.