For Iraqis, two key events last week will shape the rest of this year, but hopefully not many more to come. First, on June 8 the country’s divided parliament voted in surprising harmony to pass the so-called “Food Security and Development Bill,” a controversial piece of legislation with a IQD25 trillion ($17 billion) price tag. There are lingering questions about its legality as well as fears that it could allow untransparent spending of part of Iraq’s crude oil export windfall for 2022.

Second, this was followed, almost overnight on June 9, by a call from firebrand populist Shi’a cleric Muqtada al-Sadr to lawmakers loyal to his movement to “prepare their resignations.” Mr. al-Sadr, who earned international fame for leading an armed struggle against U.S. forces during the American occupation, has since grown more accustomed to outlandish political games. This has been especially true of late, as Iraqi politics have been gridlocked for the past seven months following the early parliamentary elections held on Oct. 10, 2021.

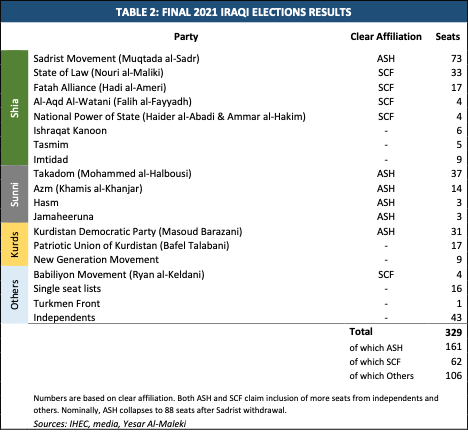

Mr. al-Sadr, whose bloc won the most seats in the October vote, allied himself with the Masoud Barzani-led Kurdistan Democratic Party and Takadum, a Sunni bloc headed by Parliament Speaker Mohammed al-Halbousi. The grouping, which aimed to form what could have been Iraq’s first post-2003 “national majority government,” recently even branded itself as the “Alliance to Save the Homeland (ASH).” Their rival, the Shi’a Coordination Framework (SCF), a loose grouping made up primarily of traditionalist Shi’a political parties, sought a “national unity government” instead. Iraq’s nearly-two-decade-old political model ensures an ethno-sectarian power-sharing structure, even to some extent regardless of election results — especially for established but underperforming parties. More importantly, the SCF saw Mr. al-Sadr as a troublemaker who had to be brought back, one way or another, into the fold as part of the “Shi’a House.” Consolidating the Shi’a parties in its backyard is also an important consideration for Tehran.

With him tossing the ball of government formation to the SCF and even independent MPs in the past few months, Mr. al-Sadr’s call on the evening of June 9 may have been seen as another fit thrown or simply a tactic. But lo and behold, on June 12, the 73 MPs of the Sadrist Movement tendered their resignations, and Iraq leapt even deeper into the void of political uncertainty.

Why the bill?

Before delving into the scenarios of what might happen next, it is important to first look at the Food Security and Development Bill passed by parliament. Its timing is crucial to understanding what the political class really prioritizes, and potentially Mr. al-Sadr’s larger game.

The bill was passed by a majority of MPs, 273 out of the total of 329. It saw the SCF and the ASH come together despite weeks of mutual recriminations. Even the Kurds, who were allocated little to nothing, voted in favor.

On the outside, the bill aims to tackle many problems. Chiefly, it allows the government to access necessary financing as the passage of a much-needed federal budget for 2022 has been hindered by the delayed government formation process. On May 15, Iraq’s Federal Supreme Court ruled that Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi’s caretaker cabinet was only allowed to carry out “day to day” government duties as per Article 13 of the Federal Financial Management Law (No. 6/2019). What this technically means is that government spending is curtailed to a pro-rata (1/12) level of the total actual current spending for financial year 2021 that ended on Dec. 31.

In March 2022, MEES forecasted oil revenues for OPEC producers, and even if oil prices averaged $90 per barrel through the end of the year — which given the current situation is the low end — Iraq is expected to earn some $115 billion. This is $20 billion more than its previous annual record of $94 billion in 2012. Baghdad is now boasting about its record-breaking oil export revenues, some $11.44 billion for May alone. Alas, without a budget or legally binding emergency spending legislation, the monies cannot be touched — a true dilemma for the political elites in Baghdad.

Both the executive and legislative branches told the public that the main reason for this bill was food and agricultural security, hence its name. Despite the political maneuvering, Iraq’s food security challenges are quite real. Since the end of last year, global food and grain commodities prices have been on an upward trajectory after the resumption of economic activity following the coronavirus pandemic and the prolonged supply chain disruptions. Things have only gotten worse in 2022 as the Russian war on Ukraine has caused prices to skyrocket since February.

Iraq is a net food importer and Baghdad subsidizes imports as well. As a result, Iraq is expected to face growing costs and supply challenges as it works to secure its needs, just like other countries in the region. Adding even more strain, Iraqi farmers have been hit hard by drought and climate change, with surveys suggesting 37% of wheat farmers and 30% of those planting barely saw nearly all of their crops fail in 2021. Iraqis were already on the street protesting high cooking oil and flour prices just three months ago. As a result, there is widespread domestic support for addressing the issue, and the food security angle provided a solid justification for the legislation.

Moreover, the bill was also designed to resolve — albeit partially, as usual — a more common cause for protesting. When temperatures soar above 50°C (122°F) in summer, Iraqis take to the streets to demonstrate over the lack of electricity provision, an annual challenge for the government to tackle. Based on contracted energy imports volumes from previous years, Iraq depends on neighboring Iran for almost 40% of its available summer supplies, both in the form of direct electricity imports and Iranian natural gas burned in Iraqi power plants.

But Iraq has been unable to pay the Iranians because of the sanctions on Tehran’s banking sector and has amassed over $5 billion in debt in recent years. After reaching yet another agreement on debt rescheduling, Tehran gave Baghdad an ultimatum to pay its 2020 invoices ($1.6 billion) by the end of May. This prompted Iraq’s minister of electricity to personally lobby MPs to earmark sums to pay Iran in the bill. Having given up on parliament reaching consensus, the ministry resorted to declaring default. This prompted Iran to reduce pipeline gas flows on June 1, and as a result, longer power cuts were experienced countrywide.

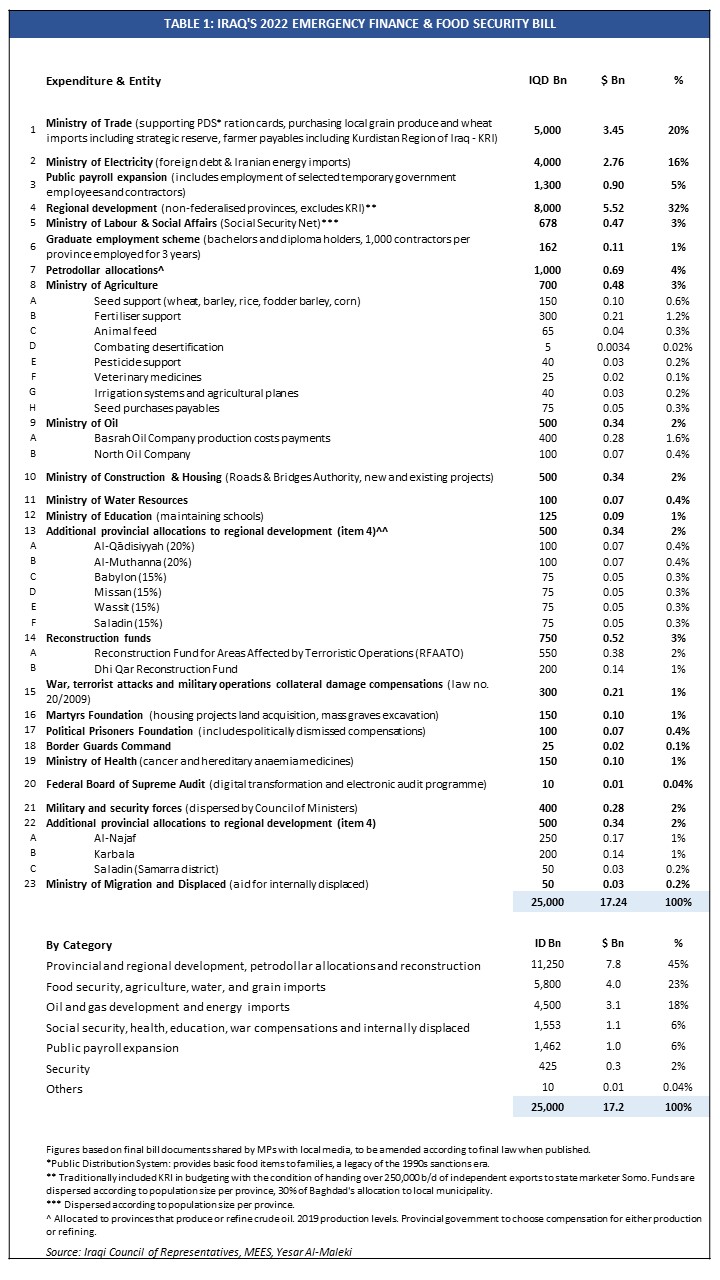

The cart before the horse

These were the pretexts upon which the bill was justified. Yet, the devil is in the details. The final bill passed allocated just $4 billion, or 23% of the $17 billion total, for food security, agriculture, water, and grain imports when the individual allocations per itemized expenditure and government entity are tallied (see table 1). As for the Ministry of Electricity, $2.76 billion (16%) was tabled for “external debts and payables for purchasing and importing gas and power.” These should cover the Iranian debt and payments owed to independent power producers in the country. In other words, only 39% or $6.76 billion went to finance the issues that the bill was originally advertised as addressing.

In reality, most of the spending, $7.8 billion (45%), will instead go to the provinces either directly depending on their population size or via petrodollar allocations if they produce or refine crude oil. In both cases, Iraqi Kurdistan will not receive a penny. This sum also includes allocations for reconstruction funds in liberated areas of the country and the socio-economically troubled Dhi Qar Province.

While the federal Ministries of Finance and Planning are expected to approve, disperse, and follow up on these funds as they traditionally do, the initiative and final say on how they are to be spent will sit with local provincial governors in coordination with the often politically appointed middle management and their complex web of bureaucratic committees.

Hence, this may create ample space for corruption, either through evasive contracting processes or even unnecessary bloating of the payroll via questionable projects and programs. Transparency — or lack thereof — was a major concern for observers in the run-up to the bill’s passage. On the payroll expansion end, the bill swelled it by another $1 billion (6%) by offering employment to temporary and contracted workers and even creating a graduate scheme (see table 1). This amount was almost equal to the $1.1 billion allotted for social security, health and education, war compensation, and the internally displaced.

There are several reasons for the broad political consensus to pass the bill. In addition to attempting to bypass the legal constraints imposed upon the caretaker government as aforementioned, the bill provides a lifeline for political blocs to continue their stalemate for the months to come. It was hoped that with Iraqis struggling economically and the government unable to tap the oil money, politicians would put the country first and reach a long-awaited grand deal on government formation.

But the emergency spending bill was created with the objective of curbing potential public outcry. It secures wages vital to sustaining Iraqis’ daily lives while providing the funds to alleviate — even if only partially — high food prices, thus allowing all parties to continue their stalemate with minimal popular resistance.

Furthermore, neither the SCF nor the ASH would have dared hinder the bill and risk their position in the continuing standoff. The Kurds, despite their ongoing dispute with Baghdad over the constitutionality of their independent oil sector, were smart enough not to stand in the way and become a scapegoat. Even Mr. al-Sadr only made his move after the bill successfully passed; if his MPs had resigned while parliament was still drafting the bill, the SCF would have branded the Sadrists as obstructionists.

But the far greater consideration for all parties is that how these funds would also help revive the activities of the often-overlooked “economic committees” that each side has established to influence contracting decisions and gain financially as a result. After all, running a political movement in Iraq is not cheap — mouths must be fed, loyalties bought, militias armed, and operations sustained. This is especially the case when traditional foreign backers are either reeling under sanctions or have grown tired of wasting their money on regional adventurism.

The next six months will be a crucial fight for financial survival among the major players, and raiding contracts requires a well-oiled and endowed government. The finances and more crucially employment opportunities will also be key in winning over regular Iraqis. Former PM Nouri al-Maliki’s rebound in the latest elections could be attributed to maintaining his influence in institutions and sustaining a system of favors that won him some popularity after years of blame. The Sadrists undertook a methodical takeover of key government positions in the last three years to counter their rivals’ decade and a half head start. Hence, it was out of question for all involved to even consider resigning — or any major political move — before the emergency financing bill was passed.

Into the political void: What happens now?

There are two considerations to think of in the immediate term. First, what will Iraq’s Independent High Electoral Commission do? And second, have the Sadrists decided to abandon the “political process”?

On the former, the fifth section of Article 15 of the Iraqi House of Representatives Elections Law (No. 9/2020) clearly dictates that “if a seat becomes vacant, the candidate with the highest score in the electoral district shall replace its holder.” This is expected to cause a dramatic change of fate for the SCF, especially in southern provinces where they closely trailed the Sadrists.

With their seats potentially bolstered, the SCF may come closer than they ever have in the past seven months to forming a government. But they still need to bring together at least two-thirds of parliament (220 seats) to do so. Even if the SCF takes all of the clearly affiliated Shi’a seats in parliament — inclusive of the 73 abandoned by the Sadrists — amounting to 151 in total (see table 2), they will still be 69 seats short.

In other words, they cannot form a government unless they ally with what remains of the ASH — the major Sunni and Kurdish political players. Without a doubt this was part of Mr. al-Sadr’s decision making.

There are two potential scenarios moving forward. The first is for the SCF to attempt to form a government after reaching an agreement with the Kurds and Sunnis. Independents and other seat holders would likely come through as the country overwhelmingly wants an exit from the current gridlock. In such a case, the Sadrists would be left as opposition outside parliament. Thus far, this seems to be where the SCF is heading. On June 14, it voiced “respect for the Sadrist decision” and called for “all Iraqi political parties to join dialogue to form a strong government.”

The risk here for the SCF and the new government is that Mr. al-Sadr — and his hundreds of thousands of loyalists — would bring down such a government in a matter of months after its formation. This is not beyond comprehension. After all, the Sadrists rode the wave of the Tishreen protests in late 2019 that brought down the Adil Abdul-Mahdi cabinet, and a repetition of the “blue hats” experience — when Mr. al-Sadr tasked his followers with protecting demonstrators, only to later abandon them — is very much feasible given Iraq’s sustained socio-economic woes. But even here, the SCF may not be as ill-prepared as some of its key constituents were in 2019. After all, the fall of Mr. Abdul-Mahdi’s cabinet was a lesson to learn from.

The second scenario is for the SCF to mitigate Mr. al-Sadr's plans and instead offer the Sadrists cabinet positions in the next government. Of course, this would be done as a compromise to unite the Shi’a House and by extension all political players in the country, as well as in recognition of Mr. al-Sadr’s influence and his movement’s rights as the biggest winners in the elections.

This is actually a beneficial scenario for the Sadrists as it allows them deniability of responsibility for the country’s political and economic challenges. Being excluded from government and undermined by other Shi’a parties had always been the line treaded by Mr. al-Sadr and his movement to divert any blame. Had he formed a government, such excuses would no longer work. More importantly, this scenario allows the Sadrists to maintain their grip on key government positions.

But even here, Iraq’s politics are hard to predict. Personal and historical feuds could re-emerge, making it difficult to reach a compromise. The politicking is expected to last longer now and in the worst of cases, if neither party is pleased, the odds of settling things with arms are still not very farfetched.

Farewell ye year of windfall?

On a final note, Iraq’s politics have once again complicated its economic trajectory. Oil prices are likely to remain at high levels for the next few years. The International Monetary Fund expects them to bring oil exporters in the Gulf around $1.4 trillion in additional revenue over the next four to five years.

While Iraq’s neighbors are preparing to utilize these large sums to diversify their economies and ready themselves for the coming decades where oil’s dominance in the global energy mix becomes increasingly challenged by efforts to reach net-zero emissions, Iraq’s executive branch is being buffeted by a struggle for power among the country’s politicians.

Even the Oil Ministry’s plans to spend $17 billion — directly and through investment — to take oil production capacity to 8 million barrels per day by 2028, basically the lifeline for Iraq’s economic existence, are jeopardized. In the recently passed emergency spending bill, the ministry was only allocated $340 million. Without a budget and a stable government, even the reforms needed to escape oil dependence under Iraq’s ambitious White Paper will have to wait. Increasingly, with all the endless political wrangling that has gone on since 2018, the tenure of an Iraqi cabinet is becoming two years at best rather than four.

Yesar Al-Maleki is an energy economist and consultant with an extensive knowledge of the intertwining subjects of energy, geopolitics, and economics in the region. He is also a non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute (MEI).

Photo by Iraqi Parliament Press Office/Handout/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

MEI is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.