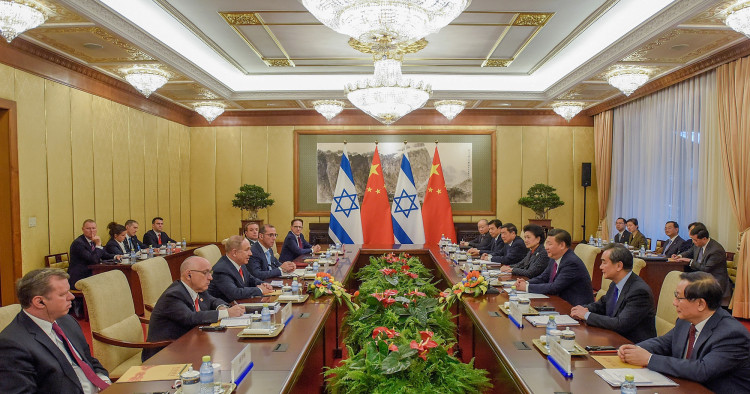

Over the past two decades, relations between Israel and China expanded significantly, encompassing trade, investment, educational partnerships, and tourism. Meeting in Beijing with the heads of large Chinese corporations in March 2017, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu described Israel’s relationship with China as “a marriage made in heaven.”

Since then, however, there have been indications that the growth prospects for the bilateral relationship have diminished. China’s stance on the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attack and on Israel’s conduct during the ensuing war in Gaza, in particular, has further cast doubt on the future trajectory of the relationship.

The Sino-Israeli romance

January 1992 marked the official establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries. Even before the formalization of diplomatic ties, China and Israel had already set up representative offices in Tel Aviv and Beijing, functioning as de facto embassies. Once out of the shadows, the bilateral relationship steadily progressed.

Mutual trade has expanded rapidly, positioning China as Israel’s second-largest trading partner after the United States. This surge in trade volume primarily reflects Israel’s increased imports from China, which more than doubled between 2012 and 2022 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Trade between Israel and China, 2012-2022 (billions of $)

Source: UN Comtrade

Chinese investment primarily flows to wealthy countries, while Chinese construction typically takes place in developing countries. But Israel is an exception, being both a developed country with a sizable, advanced tech sector and a node in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Chinese investment in Israel rose dramatically between 2007 and 2020. According to data from the Tel Aviv-based Institute of National Security Studies (INSS), China’s investments and mergers and acquisitions (M&As) in Israel have predominantly targeted the technology sector. Serving as the institutional framework for this collaboration is the Israel-China Joint Committee for Innovation Cooperation, formed in 2015. Chinese industry giants including Alibaba, ChemChina, Kung-Chi, Legend, Lenovo, and Xiaomi have all made inroads into Israel. Many of these ventures have centered on companies specializing in cloud computing, artificial intelligence (AI), semiconductors, and communication networks.

Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have carried out a slew of major Israeli infrastructure projects, including ports, metro transport, and electricity supply (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Select Israeli infrastructure projects executed by Chinese SOEs

|

Chinese companies |

Infrastructure projects |

|

China State Construction and Engineering Company (CSCEC) |

|

|

China Civil Engineering Construction Company (CCECC) |

|

|

China Harbor Engineering Company |

|

|

China Power (CHEC) |

|

|

Longxin Construction Group |

|

|

China Railway Tunnel Group |

|

|

China Railway Engineering Equipment Group |

|

|

Shanghai International Port Company (SIPG) |

|

|

Shenzhen Metro |

|

Source: Jerusalem Post and other sources

Over the past decade, as the relationship between China and Israel deepened, educational exchanges and partnerships also increased. Israel’s Technion Institute of Technology and Shantou University in China established a branch campus in Guangdong Province. Similarly, the University of Haifa and East China Normal University built a joint research institute in Shanghai; Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and Jilin University set up a joint center for entrepreneurship and innovation; and Tel Aviv University partnered with Tsinghua University in Beijing to build the XIN Research Center, focused on early-stage and mature technologies in biotech, solar energy, water and environmental technologies.

Israel has invested significant resources in attracting Chinese tourists in recent years. In 2019, Israel welcomed over 150,000 visitors from China, a record-breaking figure, with the majority arriving as part of organized tour groups. The COVID-19 pandemic brought tourist traffic from China to a halt; it was only just beginning to recover when the Israel-Hamas war began. Indeed, in mid-2023, the Israeli Ministry of Tourism had started to implement innovative strategies to entice Chinese travelers back, notably the forging of a marketing partnership with Weibo and collaborations with online influencers. And encouragingly, the Chinese government included Israel in its list of approved countries for group travel last August. However, Chinese tour operators stopped offering tours within a few days of the Hamas attack. More recently, Chinese officials suspended sending workers to Israel.

Waning enthusiasm

Long before Oct. 7, there were already indications that the honeymoon phase in Israeli-Chinese relations could be coming to an end: a widening trade imbalance, rising domestic security concerns, mounting pressure from Washington, declining public favorability, and multiple foreign policy friction points.

First, with respect to trade, Israeli exports to China, dominated by electronic components, have experienced only modest growth, peaking at $4.77 billion in 2018. Despite China’s significance as a trading partner, the widening trade disparity, limited diversity of exported goods, and minimal potential in business service trade have prompted questions about the capacity for future trade growth.

Second, although Chinese investments constitute less than 10% of foreign capital investments in Israel, they have drawn attention from the United States due to apprehensions surrounding their involvement in technology sectors deemed to be security-sensitive. These apprehensions are shared by some former senior Israeli officials, who themselves have called for tighter oversight of Chinese investments. Concerns have also risen about the numerous Chinese cyberattacks on Israeli companies and government networks.

Israel has been increasingly responsive to US concerns and to the need to protect its own security interests. Over the past several years, Israeli capital market regulators blocked Chinese-linked acquisition deals for insurers Phoenix Holdings and Clal Insurance Enterprises Holdings Ltd. In 2019, Israel established the Committee to Inspect National Security Aspects of Foreign Investments, an investment-screening entity to intensify scrutiny of specific inbound foreign investments. Since then, there has been a “marked slowdown in new deals,” especially in critical infrastructure; moreover, of the several bids won by Chinese companies, all have been small-scale projects. In July 2022, Bloomberg reported that ties in the tech sector had eroded. Two years of pressure from the Biden administration to limit China’s role in sectors such as energy, infrastructure, telecommunications, and transportation yielded a decision in November 2022 by Israel’s Security Cabinet to significantly strengthen government oversight on foreign investments. The Israeli Ministry of Defense recently released guidelines aimed at identifying efforts to exploit Israeli-developed defense technologies by China. In January 2022, Israel rejected Chinese companies that had tendered bids to build the Tel Aviv light rail green and purple lines. This February, the Israel Ports Development and Assets Company disqualified China Harbor Engineering Company (CHEC) from competing for a tender to establish a distillery port in Haifa Bay, citing “national security” interests.

Third, Beijing’s strategic messaging campaign to curry favor with the Israeli public, which as recently as 2019 appeared to be succeeding, has faltered. Findings from a 2022 Freedom House public opinion survey indicate a decline in positive perceptions of China among Israelis, dropping from 66% to 48%. Favorable views are especially low regarding Xi Jinping’s leadership on the global stage, with only 20% expressing trust in him as a world leader. Interest groups have weighed in with criticism as well. The Israel Builders Association (IBA), for example, has complained of unfair competition in the infrastructure market. The announcement last June that Prime Minister Netanyahu would be visiting China — a trip that did not take place — garnered stern criticism from former senior military and intelligence professionals. All told, the bloom is off the rose.

A critical juncture

After the Oct. 7 Hamas attack on Israel, China publicly declared neutrality but effectively sided with one party. Beijing refrained from condemning Hamas, which it has not formally designated as a terrorist organization. A week after the attack, Chinese officials stated that Israel’s airstrikes had “gone beyond self-defense” and condemned them as “collective punishment.” Since then, China, along with Russia and Iran, reportedly has been utilizing state media and social media to undermine Israel and the US and to back Hamas.

Chinese officials have occasionally met with Hamas leaders, although those meetings were seldom made public. The first publicly acknowledged meeting between Chinese diplomat Wang Kejian and Hamas political leader Ismail Haniyeh, in Qatar, might signal Beijing’s desire to demonstrate that, contrary to the views of its critics, it is indeed actively pushing for a cessation of hostilities.

Chinese container shipping lines COSCO and OOCL have suspended trade with Israel since Yemen’s Houthis declared they were targeting ships in the Red Sea linked to Israel — actions that Shaul Schneider, chairman of the board of directors of state-owned Ashdod Port, described in a Jan. 17 letter as equivalent to a “trade boycott on Israel.” In addition, amid the Israel-Hamas war, the online maps provided by Chinese technology giants Baidu and Alibaba no longer feature Israel’s name.

Commenting on Beijing’s approach to the conflict, Yun Sun, director of the China Program at the Stimson Center, noted, “China’s position on the Palestine Israel issue is very clear, very firm. And I think the Chinese, they probably want to tell the Israelis, well, don’t force us to choose, because if you force us to choose, our choice is not going to be you.” In taking such a position, Beijing’s apparent calculus is to absorb short- to medium-term damage to its lucrative commercial ties with Israel in exchange for building longer-term influence among countries where it has more extensive economic ties and where both support for the Palestinian cause as well as grievances against the US-led liberal international order run deep.

Misgivings among Israelis about the expansion of Chinese involvement in the country are longstanding, yet they have become more acute since the eruption of the conflict. In addition, policy differences with China, once possibly overlooked for convenience, have now become more pronounced. Apart from Beijing’s position on the Hamas attack and the consequent Israeli military operations, there is no policy difference with China that is more pronounced than its policy toward Iran, which is widely perceived as orchestrating strikes against Israel. China wields significant influence over Iran. However, it seems improbable that Beijing can, or even desires to, leverage this influence to deescalate the Israel-Hamas conflict.

Senior Israeli officials have reportedly conveyed “deep disappointment” to their Chinese counterparts but apparently to no avail. As Israeli military operations have continued, inflicting a devastating toll on civilians, Chinese officials have persisted in using the conflict as a means of reproaching the United States. While directing their harshest criticisms toward Washington, they have not refrained from issuing forceful critiques of Israeli policies. Addressing the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague in February, Ma Xinmin, legal adviser to China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, referred to Israel as a “foreign power occupying Palestine” and stated that the Palestinians “must not be denied” justice. During the fourth day of public hearings, China’s ambassador to the United Nations, Zhang Jun, went further, telling the court that that the use of armed struggle to gain independence from foreign and colonial rule was “legitimate” and “well founded” in international law.

Conclusion

During its tenure as president of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) in November 2023, China found itself in a familiar scenario as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict reignited, reminiscent of the events of May 2021. A year to the day before the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attack, one commentator asserted that Israel had reached a “fork in the road” with China as bilateral relations worsened, in part under pressure from Washington.

Yet in the aftermath of the May 2021 clashes, the Chinese leadership appeared to sense that its condemnation of Israel was too severe. On June 8, upon Isaac Herzog’s election as president, Xi Jinping promptly placed a congratulatory call. President Xi highlighted the increasingly robust ties between China and Israel and expressed a commitment to advancing a new level of innovative and comprehensive collaboration between the two nations. Speaking by phone later that year, Xi and Herzog reaffirmed their commitment to the China-Israel comprehensive innovation partnership. Might this time be different?

China’s handling of the current Gaza war has endangered its once flourishing relationship with Israel, a calculated maneuver to exploit the conflict to enhance its own standing while undermining that of the United States. The thinking in Beijing may be that once the situation stabilizes, economic factors will compel Israel to mend its relationship with China. However, it might be the case that Beijing has underestimated the depth of the psychological trauma Oct. 7 had inflicted on Israeli society. Beijing’s actions during the ensuing conflict are likely to have reinforced the belief among many Israelis that China will exploit or endanger Israel to advance its own interests. Although Israel may find it impractical to completely disengage from China — and is unlikely to do so — it can adopt a realistic engagement strategy without harboring any illusions, and with a new strategic understanding of its own interests.

Dr. John Calabrese teaches US foreign policy at American University in Washington, DC. He is a Senior Fellow at MEI, the Book Review Editor of The Middle East Journal, and previously served as the director of MEI’s Middle East-Asia Project (MAP).

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.