In Zarzis, on Tunisia’s southern coast, Algerian artist Rachid Koraichi has created a moving memorial to the thousands of migrants who have died crossing the Mediterranean. A hybrid graveyard, garden, and art installation, Jardin d’Afrique has become the final resting place for over 300 souls whose bodies washed up on the shore of this tourist town. An historic Phoenician and Roman port and still a hub for fishing and agriculture, lately Zarzis has become known for more grisly cargo. According to the IOM, over 866 people have died crossing Mediterranean so far this year — compared with 350 a year ago.

When the renowned Paris-based artist first visited Zarzis in the spring of 2018, he says, in an interview in French from Tunis, “There was a mountain of corpses, piled in city garbage dumps.”

First alerted by his daughter Aicha, who saw images of the bodies on social media, he was “terrified” by what he saw. “It was beyond belief,” he relates.

Bodies washed up on Zarzis’ beaches are not only bloated, he notes, but “they come in pieces.”

After witnessing such horror, Koraichi resolved to honor drowned migrants by literally picking up the pieces of their lives, giving them proper burials, and notifying their relatives. He remembers seeing a newscast at the time of his first visit about a young Norwegian boy who drowned in the sea, one that drew global media attention. “There are dozens of babies dying daily in Africa, but no one talks about it,” he observes. “They have found 25,000 corpses in the Mediterranean since 2010.”

A tragic legacy

Koraichi sees the unfolding saga as a tragic legacy of colonialism, akin to the “remains of Native children in Canada found in unmarked graves.” But, he says, “colonialism is worse today because it’s hidden.”

The artist sees his mission as a process of making visible the human carnage of the West’s overthrow of Moammar Gadhafi and the ensuing violence and chaos that has affected the entire African continent and beyond.

“No one asks, ‘Why are there so many corpses in the sea?’ The problem is the overthrow of Gadhafi. No one in France talks about it, but to butcher an African leader like that — it’s like nothing. Can you imagine if it happened to a European head of state?”

Now, explains Koraichi, “all the arms sold for millions to Libya — by France, Italy, the UK, and Germany — are now in the hands of terrorists throughout Africa. But no one takes responsibility for these genocidal arms sales.” As terrorized Africans continue to flee to European shores, he says, “It’s abominable what is happening here. People have to come and see for themselves.”

From a long line of Sufis and an active member of the Tidjaniya tariqa, an order known for their social reform and long resistance to European colonialism in Africa, Koraichi combines mysticism with activism. After consulting with the local representative of the Red Crescent in Zarzis, Muji Slim, and the mayor, in whom he found “very co-operative partners,” Koraichi bought a large tract of agricultural land (2,500 square meters) near the seaside garbage dump where so many migrants bodies were piled, and walled it off “like a crime scene.” Locals refused to bury them in their own cemeteries, often on the grounds that the many Buddhists from Asia and Christians from Sub-Saharan Africa should not be buried in Muslim plots, and because of what Koraichi cites as “overt racism.”

A walled garden

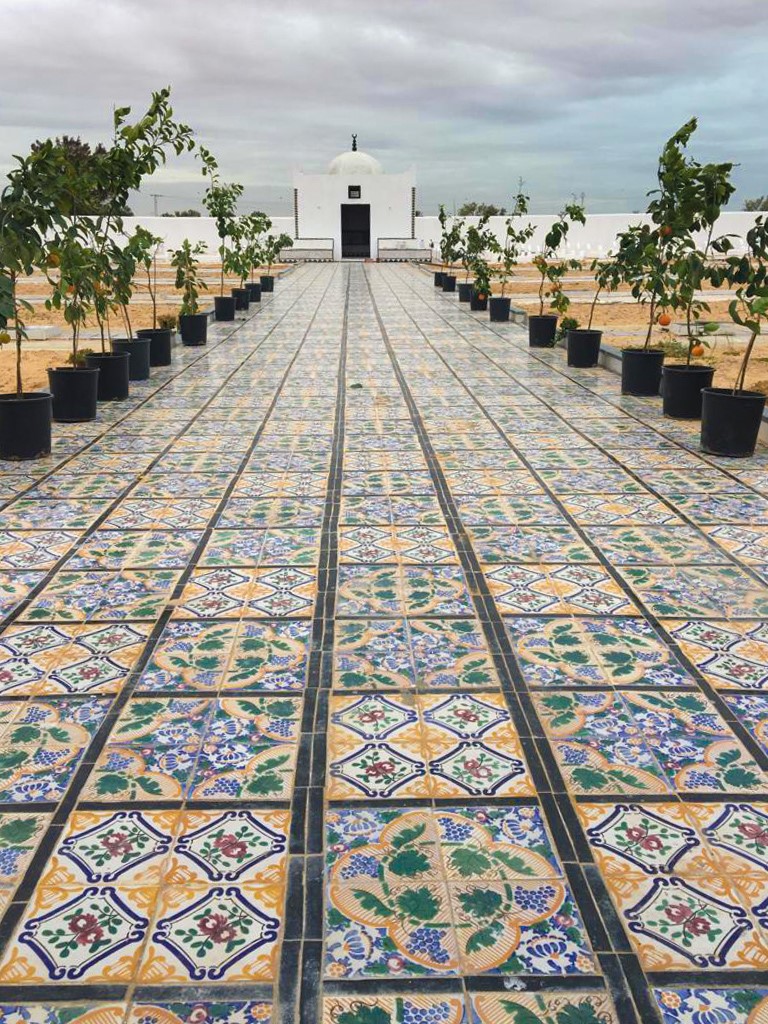

Slowly, painstakingly, and using only his own funds, Koraichi — working with a local team on the ground — realized his vision of creating a walled garden containing a non-denominational cemetery, a morgue (as an alternative to transporting the bodies 160 km away to Gabes), an interfaith prayer hall, and a DNA database for identifying the dead and contacting their families. Here 600 geometrically laid out tombs are shaded by trees, flowers, and scented herbs. 17th century Tunisian tiles from Nabeul, hand-fitted by local artisans, that cost “three times the price of the land,” covering the walkways dividing the rows of tombs, are decorated with talismanic glyphs, hearts, and other auspicious signs — a common theme in Koraichi’s work. Guardian figures keep watch and pray over the dead while an actual guardian lives on the premises and keeps them physically secure.

“Locals didn’t want them to be buried in their cemetery,” he says, “so I made my own.”

Now, the Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Egyptians, Libyans, Sudanese, Chadians, and others he calls “a U.N. of the dead” are in a place “100 times better than the locals.”

Set in a field of olive trees, the cemetery consists of a long wall with openings, “for the souls of the dead to be able to see far off into the countryside.” A 17th century door, painted yellow to represent the desert sun, is set low so that visitors must stoop as they enter in a gesture of deference to the dead. Once inside, they are greeted by a 130-year-old olive tree, symbolizing peace.

Five olive trees represent the five pillars of Islam: the profession of faith (shahada), prayer, alms giving, fasting, and pilgrimage (hajj), while 12 vines represent the 12 disciples of Jesus. Another 17th century door opens to the interfaith prayer room, “to give it the feeling of a palace,” says Koraichi.

This garden of paradise is both aromatic and symbolic. As the artist explains, bitter orange trees represent both the hardships of life and its sweetness. Pomegranates were planted for their potent Sufi symbolism as “rubies encased in each other.”

“The lone seed is fragile,” says Koraichi, citing an old proverb, “but together, the fruit is hard. One person is vulnerable, but humanity is strong if we stand together in unity.”

A variety of African and Persian jasmine flower perfume the air, while bright red Bougainvillea represent the blood of Christ and “the oxygen of life.”

A large apartment for the groundskeeper and two big offices that act as documentation centers, complete the complex.

For now, the bodies that have had DNA tests have the results recorded on their tombstones, along with the date and place of the shipwreck, and some identifying signs like age, sex, and the clothes they were wearing. In the future, with proper funding and cooperation from foreign ambassadors, says Koraichi, thisdata will help family members locate their loved ones.

“We have to live together in peace”

While some Tunisians have reacted negatively to the project, notes Koraichi, saying “‘Why is a ‘stranger’ (an Algerian) coming here to do this,’ I say we are all humans made by the same God. We have to live together in peace.”

Indeed, when the Jardin d’Afrique was officially unveiled on June 11, in a special ceremony attended by UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay, Koraichi arranged for prayers to be said by the rabbi of Djerba — from one of the world’s oldest synagogues — the Catholic archbishop from Tunis, and the local imam.

Azoulay laid a plaque on site, reading in French “In homage to the drowned who have perished in the search for a better life, and in recognition of the commitment of the artist Rachid Koraichi in fighting indifference and offering a final resting place with dignity.” But UNESCO is not funding the project and the absence of many African ambassadors the artist had invited was disheartening.

“There are more and more corpses arriving every week,” laments Koraichi, “and soon the cemetery will be overwhelmed.”

While the artist has two exhibitions in November — one at the Centre Pompidou in Metz, near Strasbourg, and another at Aicon Gallery in New York — and a recent exhibition at London’s October Gallery featured work inspired by the Jardin d’Afrique, a planned retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was foiled by COVID.

“I can’t afford to continue subsidizing the project on my own,” he says, “I need to find donors to finance the growth of the garden and pay for its upkeep.”

To that end he is working with ambassadors and hoping that the upcoming Francophone Summit in Djerba in September will be a place to find donors.

While the migrant crisis shows no signs of abating, in the future and with the right funding, Koraichi hopes that the neighboring buildings currently rented by IOM and the UNHCR, could become an art school for children, and the garden, a lasting monument to honor the dead and foster peace and reconciliation.

But for now, there is the urgent matter of finding enough room for all of the bodies. “I couldn’t bear to throw them back in the dump,” sighs the artist.

“These people were abandoned by the world, by the same powers that caused their fate. We can’t forget them.”

One can only hope that until further funding materializes, Koraichi’s talismanic signs will protect the migrants on their final journey home, as they rest peacefully in this magical place.

Hadani Ditmars is the author of Dancing in the No-Fly Zone: A Woman's Journey Through Iraq, a past editor at New Internationalist, and has been reporting from the Middle East on culture, society, and politics for two decades. Her book in progress, Between Two Rivers, is a political travelogue of ancient and sacred sites in Iraq. The views expressed in this piece are her own.

Photos courtesy of the artist.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.