In addition to investing billions in the domestic economy, Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) has also made smaller and less eye-catching investments in other countries in its neighborhood. These investments can not only foster knowledge exchanges to help diversify the Saudi economy, but they’re also important tools of economic statecraft as Riyadh strengthens its position around the Red Sea and in the Levant. Jordan, strategically located in both these regions, has historically been a major recipient of Saudi aid, but Saudi Arabia’s new leadership has pared down its aid commitments and instead started experimenting with the role of a deep-pocketed investor.

In the last decade, Jordan has made efforts to attract more foreign direct investment (FDI) and improve its economic position by modernizing its investment laws and announcing multiple plans to develop its economy and drive down unemployment. In 2017, the PIF and a number of Jordanian banks established the Saudi-Jordanian Investment Fund (SJIF) to channel $3 billion into the Jordanian economy. However, Jordan’s modernization plans have remained largely unfulfilled as yet and many of its legislative changes have not had the desired impact. Two SJIF projects provide relevant case studies: One has had an auspicious start, while the other has faced a series of missed deadlines and targets that have outpaced capacity. If these projects are anything to go by, Jordan’s broader efforts to put its economy on track are likely to face a number of challenges, even with billions of dollars in FDI.

Jordan has long faced high unemployment, far outpacing the rest of the Middle East and North Africa region, as well as sluggish per capita GDP growth and low levels of labor participation. In 2022, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reported that Jordan’s productivity growth had been stagnant for years and that an overreliance on a small number of industries — real estate, construction, and fossil fuels — had hampered its economic development. Additionally, instability in neighboring countries has limited regional trade integration and the associated economic benefits.

To address these issues, Jordan has established a cottage industry churning out economic development plans, including the Jordan 2025 Vision announced in 2014, the Jordan Reform Matrix launched in February 2019, the 2018-2022 Jordan Economic Growth Plan, and the 2019-2020 National Renaissance Plan. The government launched its most recent economic plan in January 2022, the Economic Modernization Vision (EMV). The contents of these plans are largely similar, with a focus on expanding domestic value-added manufacturing, reducing unemployment, bringing more women into the workforce, and increasing export earnings. To date, however, the results have broadly fallen short of the aims laid out under these plans. Since the Jordan 2025 Vision was released, youth employment has risen sharply, from 27% in 2015 to 41% in 2021; the national unemployment rate has doubled; and annual GDP growth has not once reached the 4.8% target.

Despite the lackluster results of its past plans, Jordan believes that the $58 billion EMV will, between 2023 and 2033, lead to the creation of 1 million jobs, a 5.6% annual growth rate, a doubling of the female labor force participation, and a 3% annual increase in per capita income. Roughly three-quarters (~$42.3 billion) of the $58 billion is slated to come from private investments, such as FDI, domestic investments, and public-private partnerships. To attract some of that money, Jordan has made changes to its investment laws.

While Jordan’s economic development plans have had limited success to date, successive legal developments have slowly improved its investment and regulatory environment. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), attempts to close tax loopholes and limit tax evasion have had a noticeable positive impact on state revenues, as have new electricity tariffs. To spur investment, in 2016 the government passed the Investment Fund Law, article 4 of which reserved certain major infrastructure projects — for example, the national railway, cross-border electrical infrastructure, and oil pipelines — for entities affiliated with Arab sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) and foreign investment funds. Unfortunately, while the law specifies that such funds must be incorporated under special provisions to gain access to these projects, these special provisions do not appear to have been defined, nor are state-owned enterprises, and therefore SWFs, clearly defined under Jordanian law. To the best of my knowledge, only one such entity was formed: the SJIF, discussed below.

In January 2023, the new Investment Environment Law came into force. It aims to regularize taxes, ease administration by setting up an electronic platform accessible to all relevant authorities, and speed up the approval process for registering and licensing entities. Articles 9 to 13 list a number of incentives, some of which are similar to the 2014 Investment Law, such as tax breaks for business activities in less developed areas, but the new law has several additions: a new “Jordanianization” clause, allowing entities that employ at least 250 Jordanians to become eligible for a drastic reduction of or exemption from income tax for five years; tax exemptions for export-focused companies; potential tax exemptions for companies that employ at least 50 Jordanian; and tax exemptions for companies involved in technology and knowledge transfers.

The new Investment Environment Law also targets sectors that the government considers strategic, including healthcare and education, and gives them blanket exemptions from income tax for five years. The Investment Environment Law is therefore more aggressive than previous legislation in achieving three long-term goals: reducing unemployment; bringing more women into the workforce; and developing local industries, especially in the healthcare, transport infrastructure, and export sectors. Whether the Investment Environment Law will manage to mobilize the $42.3 billion in private investments required for the EMV will be its primary measure of success, although history suggests that may be difficult to achieve.

To date, the SIJF is the only identified foreign state-owned fund active in Jordan. According to its website, it has $3 billion in capital commitments and, depending on the source, is either wholly, 92%, or 90% owned by the PIF. According to the PIF, the remaining share is held by 16 Jordanian banks. The SJIF has announced investments in two Jordanian sectors: healthcare and railway infrastructure.

The smaller of the SJIF’s two announced investments is the Healthcare Project in Amman. The $400 million project, invested through SJIF’s wholly-owned subsidiary, the Saudi Jordanian Fund for Medical and Educational Investments Company (SJFMEI), in collaboration with the UCL Medical School and UCLA Health, will consist of a university hospital with 300 beds and a 600-student-capacity medical school, and is expected to create 5,000 jobs. Once completed, it will also have four advanced research centers. In December 2022, Hill International was selected as the project’s construction manager, and the foundation stone was laid in October 2023.

The project aligns nicely with the EMV. Firstly, pharmaceutical research and production is considered a strategic sector, and the government hopes to turn Jordan into a pharmaceutical production hub. The country already has a very strong foundation: Hikma, a Jordan-founded, London-headquartered pharmaceutical company, has five manufacturing plants and two research hubs in Jordan, with a combined turnover of $349 million in 2022. Jordan’s medical sector also already enjoys a sterling international reputation: According to a 2016 World Bank report, Jordan is one of the world’s largest medical tourism destinations, and the Private Hospitals Association of Jordan estimates that around 250,000 patients visit the country each year, generating more than a billion dollars in revenue. Second, a core target of the EMV is improving Jordan’s labor force participation among women, which is extremely low at around 15% — less than half that of Oman and less than a third of that of the UAE. However, 56% of Jordanian university graduates are women, as are more than 60% of medical graduates. Once completed the Healthcare Project has the potential to be a good template for additional strategic investments in Jordan, helping to capitalize on its well-educated population, long-term stability, and strong relations with both Western countries and Gulf states to attract foreign capital and expertise to develop strategic sectors.

Aqaba-Ma’an Railway modernization

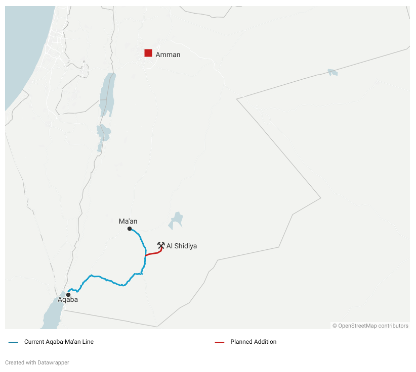

The SJIF’s second project, which is larger, more expensive, and has made less headway, is its announced investment in the Aqaba-Ma’an Railway. In February 2019, the SJIF signed a memorandum of understanding with the Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority (ASEZA) to invest JD 500 million (roughly $700 million) to redevelop the Aqaba-Ma’an Railway, build a dry port in Ma’an, and connect the Shiddiya phosphate mine to the extant rail network (see map). The project intends to upgrade the railway from its 1050mm narrow gauge built in 1975 to 1435mm standard gauge and, once completed, will form the first phase of Jordan’s new national rail network.

The SJIF’s second project, which is larger, more expensive, and has made less headway, is its announced investment in the Aqaba-Ma’an Railway. In February 2019, the SJIF signed a memorandum of understanding with the Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority (ASEZA) to invest JD 500 million (roughly $700 million) to redevelop the Aqaba-Ma’an Railway, build a dry port in Ma’an, and connect the Shiddiya phosphate mine to the extant rail network (see map). The project intends to upgrade the railway from its 1050mm narrow gauge built in 1975 to 1435mm standard gauge and, once completed, will form the first phase of Jordan’s new national rail network.

However, the project has progressed in fits and starts. Its memorandum of understanding was signed before that of the Amman Healthcare Project, but the latter has progressed much faster. According to Strategiecs, a Jordanian think tank, the feasibility study, agreed upon in February 2019, was finished in August 2020, yet no official announcement of this milestone was made. In June 2021, Jordan’s prime minister said that the government was in contact with companies to develop the project. In November 2021, Fitch wrote, “We are skeptical about the planned development of a standard-gauge railway connection between the port of Aqaba and Amman,” but noted that the SJIF’s support for the railway’s southern sector improves “the long-term outlook of the line.” Since then, there have been no official announcements on the project from ASEZA or the SJIF. In July 2023 Jordanian media reported that studies were 95% complete and work was underway to clarify the expropriation process of the public lands required for the project. In August Petra News Agency reported that the studies would be completed in September. It is unclear whether this has been delayed.

Delays to transportation projects in Jordan, especially for rail, have been common. The Amman-Zarqa railway had been in the planning stage since the late 1990s, and there has been talk since at least 2009 of updating Jordan’s railway system at a cost of $6.4 billion, with additional branches connecting the railway to Iraq and Saudi Arabia. In 2011 the Ministry of Transport published a brochure on the project that estimated the cost at $2.97 billion but would have an annual revenue of $507 million by 2020 and $738 million by 2030. So far, not a single yard of new railway has been laid, let alone started generating revenue. In June 2022, the World Bank estimated that transport-related inefficiencies cost the country at least 6% of GDP a year, or around $3 billion, due to congestion, fatalities, and environmental degradation. An additional $1 billion is spent on fuel imports, making up nearly 7% of the total state budget.

Jordan faces a major uphill battle to implement its newest modernization plan. It doesn’t have oil wealth to throw around and the instability among its neighbors — Syria, Iraq, Palestine, and increasingly Israel — have made it a tricky investment destination. However, as highlighted by the relatively fast turnaround on the Amman Healthcare Project, Jordan can effectively implement smaller-scale projects in sectors where it has historically been a regional leader. Foreign cash, whether from Gulf countries, international financial institutions, or foreign investors, is essential. Qatar’s July 2023 announcement that it would activate an unnamed $2 billion fund to invest in Jordan is therefore good news.

Yet Jordan’s failure to achieve many of its other economic development goals does not bode well for the success of the EMV. The target annual GDP growth rate of 5.6% is more than twice the IMF forecast, and while the EMV is brimming with ambition it generally lacks detail on how it will be turned into reality. The stop-start nature of the national railway project suggests that even when funds are available, implementation capability often comes up short. Whether the Aqaba-Ma’an Railway gets off the ground and manages to stay on track will be a bellwether for the other plans Jordan wants to implement, and will either serve as an encouraging sign or a warning for other investors. While recent events in Israel and Gaza have thrown a wrench into Israel-Saudi normalization talks, if Jordan wants to capitalize on warming relations and trade between these countries in the longer term, it will need to become serious not only about making plans, but implementing them too.

Piotr Schulkes is a non-resident scholar with MEI’s Economics and Energy Program. His research focuses on the role of financial institutions in economic development and the intersection of finance and renewable energy in the Gulf states.

Photo by Artur Widak/NurPhoto

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.