Summary

The Syrian Arab Army (SAA) has been decimated by eight years of civil war. Defections, deaths, and a lack of funding have gutted its ranks while heavy losses of armored vehicles have significantly reduced the mechanized capabilities of what was once the sixth-largest armor fleet in the world.1 The inability of Damascus to fully deploy its official army led to the rise of paramilitary militias and an influx of pro-regime foreign fighters. Furthermore, the way in which the SAA units were deployed, by “task-organizing” divisions into reliably loyal units of approximately one brigade, led to the disintegration of brigade-division administrative ties.

As the regime attempted to reorganize beginning in 2014 and 2015, new divisions and brigades were created based on regional deployments. This strategy attempted to address the logistical and command issues that resulted from brigades operating hundreds of miles from the rest of their division. Russia’s fall 2015 intervention also ushered in a new era of attempted rebuilding. Between late 2015 and late 2018, Russia and Damascus engaged in four distinct initiatives to both rebuild the SAA and integrate militias under Damascus’ direct control. This report details the causes of the collapse of the SAA and its attempted rebirth and ends with a detailed examination of its current order of battle.

Methodology

This first half of this report is largely based on secondary sources: detailed reports written during the first half of the war on the SAA’s structure and strategy. The rest of the report is based almost entirely on publicly available Facebook posts from the personal profiles of SAA commanders and fighters and from Facebook pages dedicated to posting media about specific Republican Guard groups. To begin, the author searched in Arabic for posts regarding SAA divisions, brigades, regiments, and battalions known to him, followed by information on other units discussed in English-language media. Throughout this process, further SAA units were identified.

When a unit was identified, all of their associated Facebook pages were fully examined for posts relating to deployments, commanders, and affiliations with other units. Next, the author searched variations of the unit’s name on Facebook to find additional posts and information. The bulk of this research focused on identifying which brigades had a social media footprint from 2017 through 2019 and which divisions these brigades were claimed to be associated with. Most posts only refer to brigade deployments, although simultaneous deployments across the country make it clear that these posts were actually referring to battalions within these brigades. Posts about specific battalions were much rarer and largely came through martyrdom commemorations. Unit affiliations were more difficult to assess, as some brigades were reported as belonging to multiple divisions simultaneously. Such cases are stated and the mixed affiliations are reflected in the orders of battle created.

Lastly, the author relied on a year-long interview with a pro-regime Syrian with extensive contacts throughout the military. The claims made by this individual, who wishes to remain anonymous for security reasons, were largely corroborated via open source material. While this methodology has led to the most comprehensive existing record of the current SAA structure, it is limited due to its reliance on Facebook posts matching the author’s search terms. Furthermore, the SAA is currently undergoing restructuring. Therefore, it is entirely possible that additional new brigades are not included in this report and that some unit affiliations are either out of date or missing.

Introduction

The SAA has, by and large, defined itself by the country’s decades-long conflict with Israel. According to Richard Bennett’s 2001 assessment of the Syrian armed forces, Israel was Syria’s “main, but not exclusive, potential enemy.”2 Thus, the bulk of the military’s armored divisions, special forces, and artillery units were “headquartered in the capital and the majority of other combat units are deployed along an arc from northwest to southwest, facing the Golan Heights and Lebanon.”3 Following the 1982 war in Lebanon, the military underwent a period of restructuring, resulting in “the main war-fighting element compris[ing] three corps formed in 1985 to give the Army more flexibility and to improve combat efficiency by decentralizing the command structure.”4 In its preparation for war with Israel, Syria’s limited military funds were concentrated on maintaining and expanding its armored fleet. In 2008, Syria reportedly operated just under 5,000 main battle tanks and 4,500 armored personnel carriers (APC) and infantry fighting vehicles (IFV).5 However, nearly half of the tank fleet and the bulk of the APC/IFC fleet consisted of highly outdated vehicles.6 Additionally, as many as 2,250 of Syria’s tanks were placed in static positions facing the Golan or in storage when the protests began in 2011.7

The evolution of the SAA between 2011 and 2019 can be divided into two periods: a time of fracturing and collapse from 2011 until late 2015 and then a prolonged and fraught period of rebuilding under the guidance of the Russian military. The collapse of the SAA truly occurred between 2012 and 2013 as the conflict turned from an insurgency into a civil war. Desertions, deaths, and general mismanagement of the army was compounded by the influx of foreign-controlled militias from Lebanon, Iraq, and Iran and the upswell of local militias across loyalist-controlled Syria. This period has been well documented and will be discussed below. Russia’s fall 2015 intervention saw the first potential for the reformation of the SAA, although it would take more than three years for these attempts to begin paying off. This period of rebuilding can be divided into four distinct initiatives occurring in late 2015, late 2016, early 2017, and late 2018. At least three of these were planned, funded, and administered by the Russians.

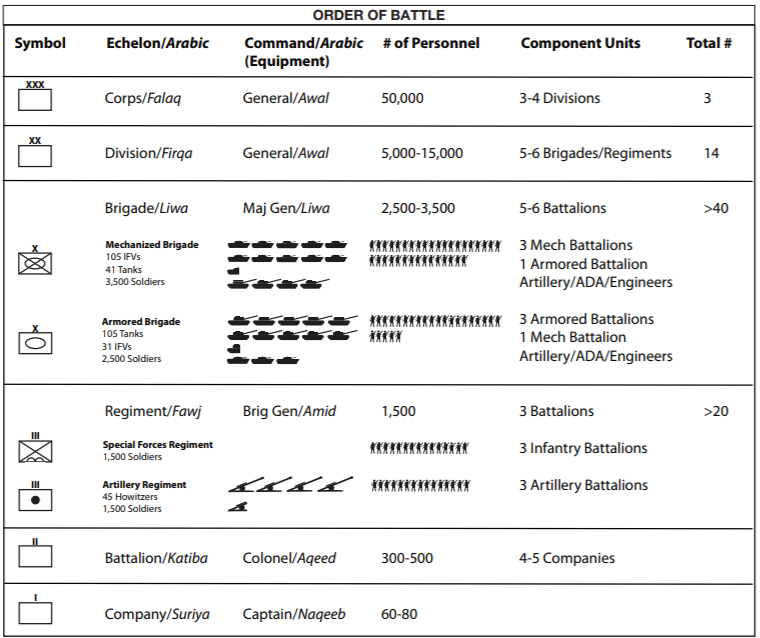

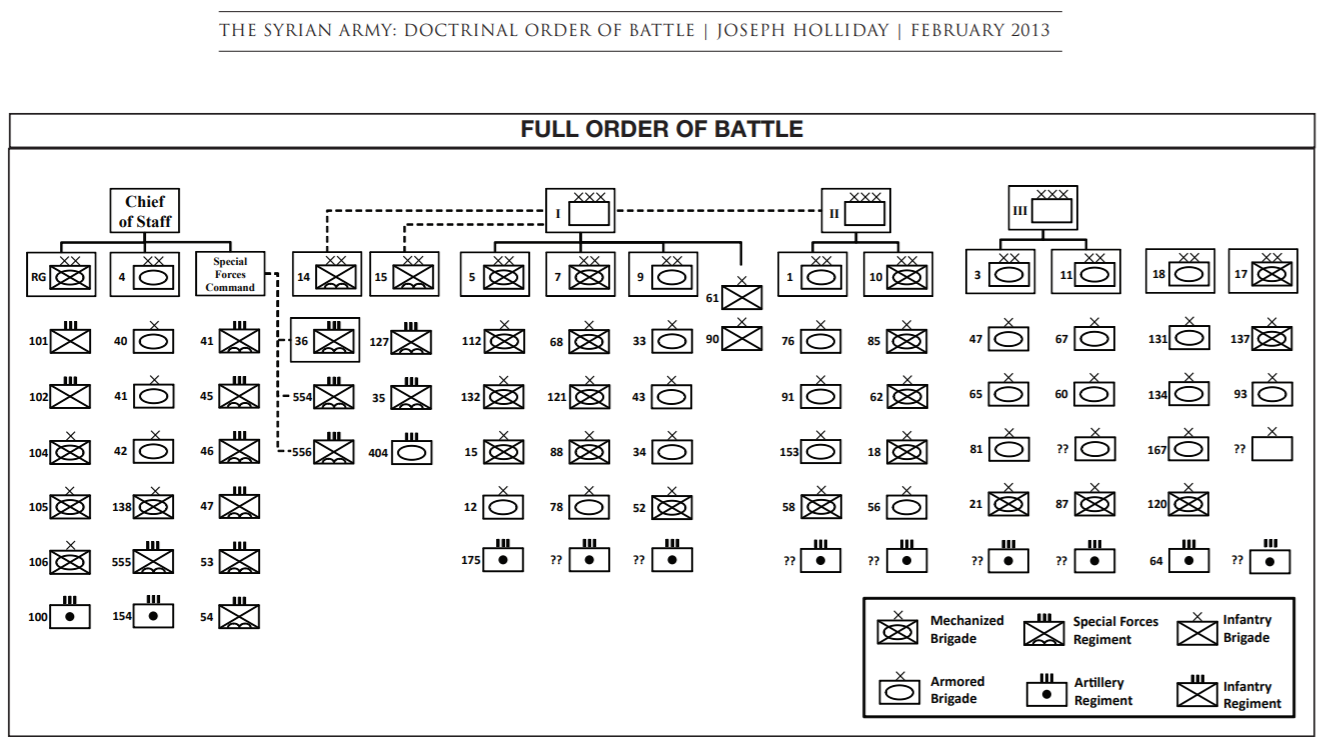

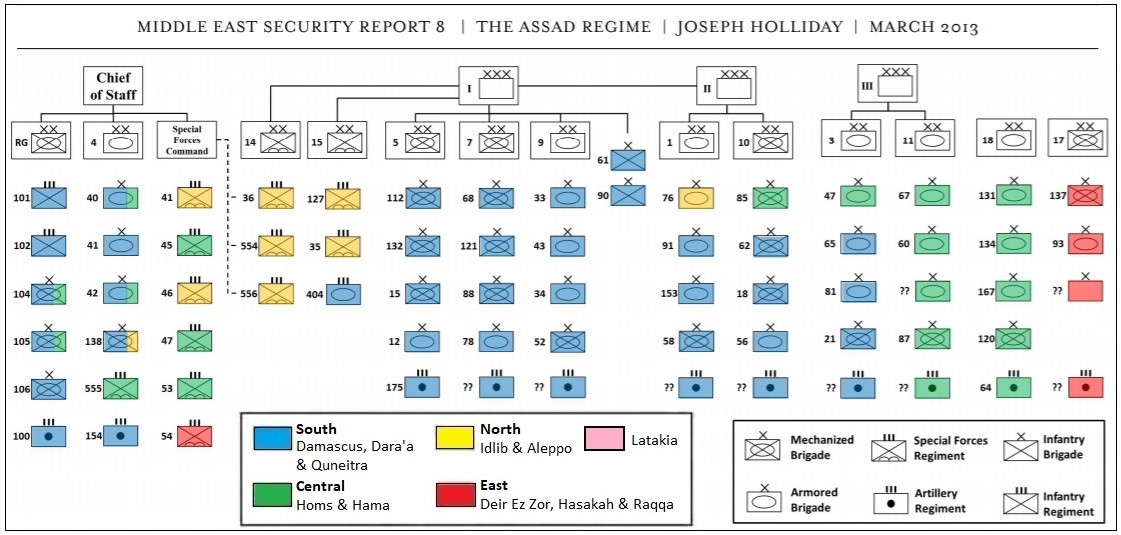

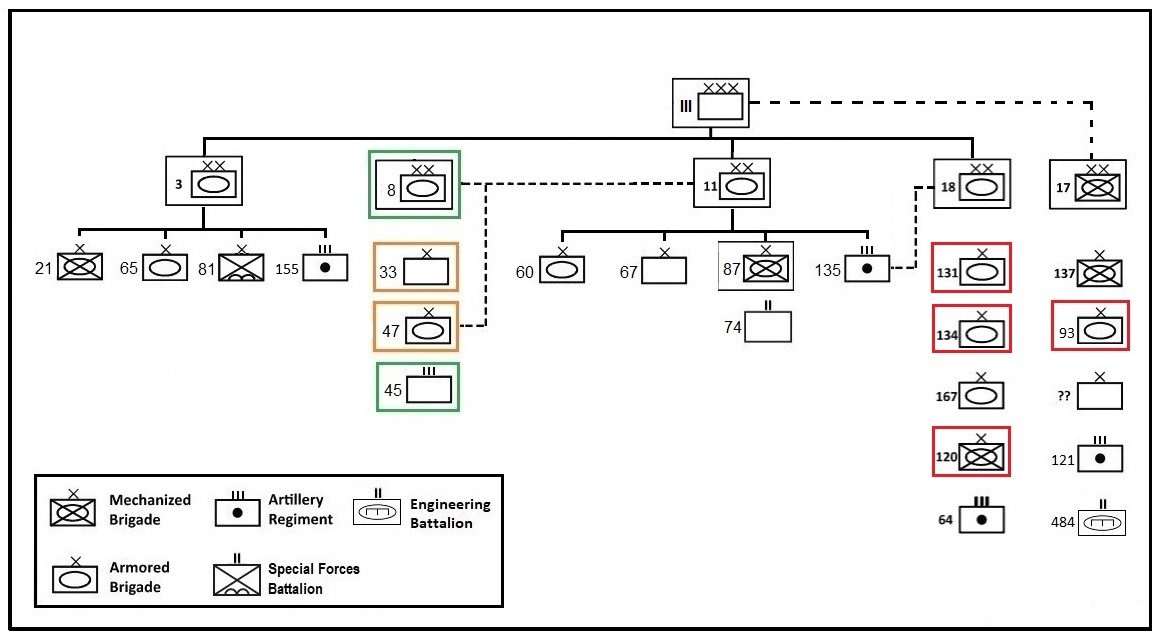

The SAA’s order of battle in 2011, according to the Institute for the Study of War, as shown in infographics below:8

Collapse

President Bashar al-Assad’s initial campaign against protestors mirrored the strategies employed by his father Hafez in the 1980s. A report by Joseph Holliday of the Institute for the Study of War describes these three combined strategies as:

- Selective deployment: Hafez depended on a handful of politically reliable units, pairing elite, all-Alawite forces with line troops to compel allegiance.

- Paramilitaries: Hafez raised pro-regime militias to supplement the armed forces.

- Clear and hold: Hafez deployed armored forces to clear major population centers, with indirect fire if necessary, and held them with a heavy garrison of troops.

Holliday goes on to state that "between March 2011 and March 2012, Bashar al-Assad generated reliable forces by selectively deploying units, raising pro-regime militias, and pursuing a clear and hold strategy in major urban areas using indirect fire."9

The key issue in the first year for Bashar al-Assad was finding SAA units that could reliably be deployed against unarmed protestors and would willingly fire upon them when ordered. “Selective deployment” was therefore used as a means to ensure all units outside of brigade headquarters would not defect. The heavily loyal, majority Alawite, Republican Guard, 4th Division, and Special Forces units were frequently deployed at the battalion and company level and attached to conventional SAA units, thus ensuring discipline and preventing defections through both field executions and detainment.10 According to Holliday, “The regime will assign one company from the loyal 4th Armored Division to work with two companies from a conventional unit. This task-organized unit then becomes a battalion,” under the flag and command of the 4th Division.11

Furthermore, conventional divisions were themselves reorganized and their four brigades were broken down and combined into, on average, one brigade’s worth of trustworthy fighters.12 It was this new brigade that would be deployed far from the division’s headquarters while the remaining units would either stay in garrison or deploy only to nearby frontlines.13 The necessity of having to split maneuver brigades into their component battalions and companies and “task-organize” as early as 2011 led directly to the severing of command capabilities and fracturing of the original administrative ties for both the Republican Guard and the SAA. It is these issues specifically that recent rebuilding efforts have sought to address.

In 2013, two years after the first anti-government protests began in Dara’a, the SAA was estimated to have lost half of its pre-war strength to defections and combat deaths.14 The same year, Holliday assessed that Damascus could reliably deploy approximately 65,000 soldiers across the SAA (including the Republican Guard and Special Forces units).15 These numbers were roughly in line with opposition assessments that one-third of the original SAA, or 75,000 men, had been deployed. An Air Intelligence commander who defected claimed that internal assessments of defections had reached 100,000 by mid-2012, while Turkish intelligence estimated 60,000 defectors.16 Thousands more Sunni officers and conscripts were either arrested or confined to their bases in these early years amid fears of further defections.17

The rapid losses experienced by the SAA, alongside its generally poor performance against the increasingly heavily armed and organized opposition, called for a change in the regime’s doctrine. Initially, the conventional units of the SAA focused on providing armor and artillery support for the Special Forces regiments and division. As these infantry units were decimated (discussed below), however, foreign fighters and motivated, skilled militias became the frontline troops.18 Assad’s priority of keeping SAA units in “every corner … north, south, east, west, and between” — as he stated in January 2015 — meant that units could never be reconsolidated and that remote government outposts were regularly overrun: in Raqqa and Hasakah in late summer 2014 and throughout Idlib in 2014 and 2015, for example.19 Assad’s second strategy — again outlined by himself in the spring of 2015 — called for legitimacy through control of the population.20

These dual policies meant the regime’s military units had to both focus on urban centers, concentrating their artillery and air power there, while also attempting to maintain some presence throughout rural Syria. However, the severe manpower shortages within the SAA made this task impossible. In 2014, Damascus launched new conscription campaigns, calling up as many as 70,000 reservists as well as arresting thousands of men for service in the first half of the year alone.21 On top of this, paramilitary militias took on a growing role, as many of the loyalist communities that had created their own armed units in response to the conflict were called upon to fight in their hometowns, while others were sent to far-flung fronts. In a speech on July 26, 2015, Assad stated that “a shortfall in human capacity” meant that the army would have to withdraw from some parts of the country.22 By the end of 2017, analysts put the number of offensive-capable fighters in the SAA at no more than 25,000 — the majority of which were in the Republican Guard and 4th Division units.23

Rise of the Militias

Private, state-backed, and foreign militias have proven key to the regime’s survival since as early as 2012. With the SAA in a state of chaos, the Republican Guard overstretched in the south of Syria, and conventional divisions largely reduced to one brigade’s worth of reliably loyal fighters, native and foreign men were called upon to defend the country. In order to address its manpower shortage, Damascus pursued three strategies.

First, it enabled the proliferation of pro-government militias through the passage of 2013’s Legislative Decree 55, which allowed for contracting private companies to protect gas and oil infrastructure.24 Some militias were affiliated with established governmental bodies, such as the Air Intelligence-affiliated Tiger Forces from Hama. The Tiger Forces leveraged the prestige and power of the Air Intelligence to unite armored and artillery units from the 11th and 4th Divisions with the remnants of the Special Forces units (particularly the 53rd Regiment) and a number of local, largely Alawite, militias that had formed in Hama and Homs.25 Other groups were formed by wealthy businessmen connected to the government, like the Jaber brothers’ Desert Hawks, a Latakia-based private militia that enjoyed the backing of the Republican Guard until it was forced to disband in 2017.26 Many more militias mobilized within key loyalist communities, like the Aleppo Palestinian Liwa al-Quds and Damascus Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command. These local militias were used both to secure their immediate surroundings (as was the case with most Damascus-based Palestinian groups) and as infantry support on farther-flung fronts. (Liwa al-Quds has a long history of fighting in Deir ez-Zor and Homs, for example.)

Second, Assad’s allies sent large numbers of foreign fighters to bolster the frontlines. By 2012, pro-Assad Iraqi militias had formed around Damascus as the sought to protect their holy Shi’a shrines from the largely Sunni opposition.27 In the same year, Afghan immigrants in Iran began traveling to Damascus under the command and pay of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) where they incorporate small local Afghan militias to protect Shia shrines.28 This Afghan contingent would eventually become a division of 12,000-14,000 fighters — deployed at the brigade level on a rotational basis — run entirely by the IRGC and staffed by Afghan refugees both living in Iran and seeking to leave Afghanistan.29 In May 2013, Lebanese Hezbollah officially entered the war, launching its first full-scale operation against the crucial opposition supply routes in the western Qalamoun mountains, northeast of Damascus.30 Finally, on Sept. 30, 2015, Russia deployed its military to Syria’s frontlines.31 Special forces, artillery, armored units, and Russian generals embedded themselves alongside pro-regime militias and official army units in the fight against the opposition.

The third and less discussed strategy is the conscription of former rebels into the SAA and affiliated militias.32 These men, locals from former rebel towns that made reconciliation agreements with the government, have taken on an increasingly prominent role among some frontline units. The recruitment paths of ex-rebels vary from town to town: in southern Syria, many have been brought into southern-based units like the 7th and 9th Divisions while others have been placed under the command of military intelligence.33 In Homs and Hama, ex-rebels largely remain in local defense forces. More recently, the Republican Guard’s 105th Brigade has begun recruiting heavily from the former opposition towns in Dara’a that fell under Damascus’ control in mid-2018.34

As should be clear by now, many of these militias operate in a grey zone between being non-state-affiliated and taking direct orders from state security forces. It is therefore sometimes difficult to determine their exact affiliation. For example, Aymann Jaber, a wealthy Alawite from Latakia, built numerous private military companies using his own funds. One of these, the Desert Hawks, remained under his direct command for the entirety of its existence.35 Another, the Syrian Marines, was eventually folded into the Coastal Shield Brigade, a separate Latakia-based militia founded with the support of the Republican Guard.36 The Coastal Shield Brigade itself would later be completely, or nearly-completely, brought under the command of the Republican Guard’s 103rd Brigade.37

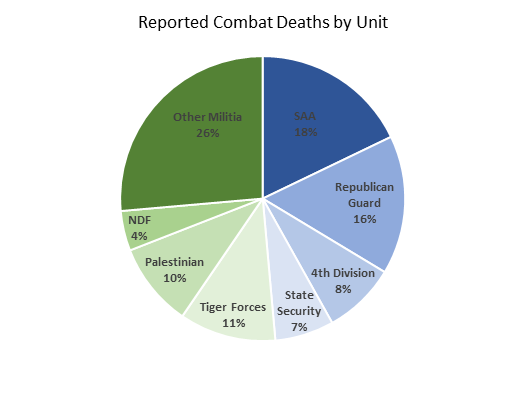

The reliance on paramilitary units is reflected in martyrdom data. Often, when loyalist fighters are killed, their personal information is shared on Facebook by their friends, family, or community. The information provided varies but can include as much as the slain fighter’s name, place of death, place of birth, rank, and unit. Examining the units reported in these martyrdom posts provides a rough picture of how Damascus has employed the plethora of units at its disposal. Of the 4,335 names this author collected between July 1, 2017 and June 30, 2018, 35 percent had units reported along with their deaths. This data is broken down below:

Conventional SAA fighters account for only 18 percent of those deaths with unit attributes, nearly equal to the number of Republican Guard deaths in the same period, even though the SAA was 11 times larger in 2011. Overall, 51 percent of reported deaths with unit attributes belonged to militias. It is impossible to know what the true proportion is as 65 percent of the martyrdom data is missing unit affiliations, but it does provide unique circumstantial evidence of the regime’s reliance on militias and the Republican Guard in frontline fighting.

The preponderance of paramilitary units and the regime’s reliance on them has not just weakened the SAA high command’s ability to coordinate offensive and defensive operations, it has also created a serious challenge to Damascus’ ability to maintain order in the areas it controls. The Desert Hawks operated with complete independence from the state and was infamous for its many war crimes. The group was finally forced to disband in the summer of 2017 after it reportedly blocked a government convoy attempting to enter an area it controlled.38 Meanwhile, the Air Intelligence-backed Tiger Forces act as a shield for the dozens of militias that operate in Hama and Homs. These militias are well-known among loyalist for their crimes against the local communities, including arms smuggling, extortion, kidnapping, and rape.39 In two examples provided to this author by a pro-government fighter in the area, the Tiger Forces’ Sahab Regiment was accused of kidnapping a cousin of Mohammad Jaber (of the Jaber family mentioned above) for ransom and recruiting people from local prisons while the Ali Sheli Hawks were accused of rape and kidnapping of pro-regime civilians.40

There have been attempts to rein in these powerful warlords and their militias in the past year (representing one aspect of the fourth rebuilding initiative that will be discussed below). In late 2018 and early 2019, the SAA high command attempted to “force” the Tiger Forces’ Homs militias to “reconcile” and officially join the SAA in what would be a newly formed division.41 This initiative, led by “the esteemed general” Major General Murad Kheirbek, now one of the commanding officers of the Russian-run 5th Corps, has failed, as the fighters have no motivation to give up the financial security and prestige afforded by membership in the Tiger Forces.42

Other attempts at reintegrating militias are in equally early stages. According to an interview, the National Defense Forces (NDF) — one of the most widespread paramilitary units — “won’t be touched for the moment,” while the Local Defense Forces (LDF) — a similarly Iranian-funded project in Aleppo — may join the local Republican Guard’s 30th Division in the coming months as they begin to lose funding from Tehran.43 Other groups, like the Aleppo-based Liwa al-Quds, will not be pressured into joining for the time being, “as long as they don't get busted with more illegal trading and corruption charges.”44 In an interview with journalist Mona Alami in spring 2019, a high-ranking commander of a pro-regime militia stated that:

“The Syrian government is progressively incorporating pro-regime paramilitary. In [this] first phase, [the government is] forcing [these paramilitary] members [who meet] conscription conditions such as age to join the Syrian army, while those who do not [meet conscription conditions] remain in their respective groups.”45

The salary for members of the SAA starts at approximately SYP40,000 ($77) for new recruits — men who have just completed their basic training — and is a bit higher for those with college degrees.46 Officer salaries range between approximately SYP50,000 and SYP81,000 ($97 and $157) depending on rank, but can reach as high as SYP100,000-120,000 ($194-233).47 These salaries have been raised four times over the course of the war: in March 2011 with Decrees 40 and 41, June 2013 with Decree 38, June 2016 with Decree 13, and an officer raise in December 2018 with Decree 20.48 Militia salaries are generally double what men would make in the SAA, not to mention the secondary income acquired from militia checkpoints set up throughout regime-held territory.49 Thus, the ongoing efforts to fold militias into the SAA have been met with considerable resistance from those enjoying higher salaries and income from criminal activities.

Rebuilding

One of Russia’s primary goals in directly intervening in Syria on Sept. 30, 2015 was to reverse the SAA’s downward spiral.50 Moscow rightly understood that the survival of the regime required the resurrection of fighting forces directly under Damascus’ (or its own) control. To this end, Russia would pursue three distinct restructuring initiatives while the Republican Guard implemented a fourth.

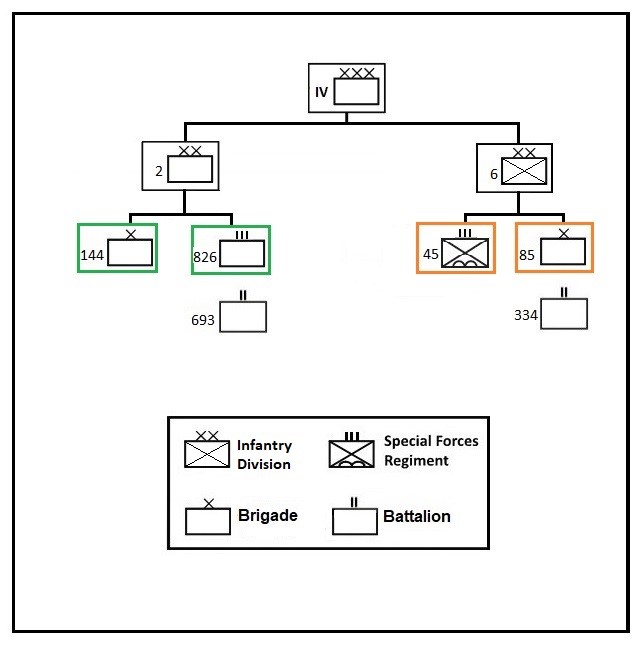

October 2015: The 4th Corps was created in October 2015 under a joint Russian-Syrian command just one month after the official Russian intervention in Syria.51 The corps is often referred to as a “storming” unit, indicating initial hopes that it would be useful for offense. However, outside of limited use in the 2016 Latakia offensives, the 4th Corps and its component units have remained on defensive garrison duty in north Latakia and the Sahel al-Ghab region of north Hama, the same regions from which the corps draws most of its recruits.52

The new corps was claimed to be formed among current soldiers and volunteers, as well as incorporating local loyalist militias, mostly NDF, from Latakia and Tartous.53 This choice of region was especially deliberate given the ongoing setbacks the regime was facing in Idlib and the northern countryside of Latakia. The geographic concentration of the new corps and the conscious effort to integrate local militias under a joint Syrian-Russian command indicates the importance Russia had already placed on expanding the SAA’s command.

A 2017 report on the Syrian armed forces by the Russian Council of International Affairs claimed the corps contained six brigades.54 However, only two brigades and two regiments could be identified through open source material. Furthermore, when asked about this claim an anonymous source with strong connections to pro-regime coastal militias stated that there were at most four brigades: the 144th and 85th, a 1st Brigade that was disbanded after six months, and a 16th Brigade that consisted of pro-government internally displaced persons from eastern Syrian.55 An assessment on the structure of the 4th Corps by the Omran Center for Strategic Studies further states that the corps only had six brigades until the end of 2015.56 Additional information on the structure of the 4th Corps can be found at the end of this report.

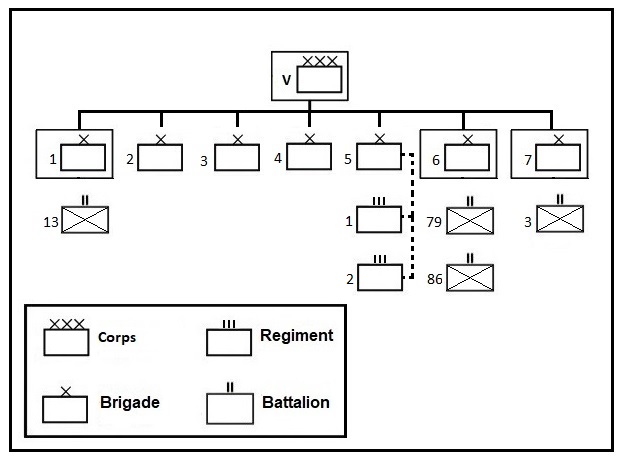

November 2016: After the 4th Corps project failed to meet Russia’s hopes, the Russian military created the new 5th “Assault” Corps in November 2016.57 It is funded, trained, and commanded by Russians, as evidenced by the death of Russian Lieutenant-General Valery Asapov on Sept. 23, 2017.58 Asapov was Russia’s chief of staff in Syria and the commander of the 5th Corps at the time of his death in Deir ez-Zor. The Russian military presence within the 5th Corps has continued to be documented since then. Throughout the first quarter of 2019, Russian military and suspected intelligence officers were regularly pictured in loyalist social media alongside brigade commanders on all fronts. Each brigade appears to consistently have the same one or two Russian officers present, and it is these officers who often present medals to the brigade’s officers. Therefore, it seems that the Syrian command structure of the 5th Corps rests beneath a Russian structure, from overall command down to brigade liaisons that help coordinate the movements of units with those of the Russian military.

The 5th Corps occupies a middle ground of sorts between historic defensive units and offensive ones. The corps has had a questionable deployment record, with significant claims of mistreatment and a lack of support from partnered Russian units, particularly during the central Syria campaign in the summer of 2017.59 At its inception, the corps was intended to draw upon the as-yet untapped population of state employees (who are exempt from mandatory service) and men who had already completed their military service.60 The hope was that by offering competitive salaries on top of the soldier’s civilian salary, a new pool of recruits would be enticed to join the SAA.61 However, the corps has since become a prominent destination for reconciled rebel factions, particularly from southern Syria. According to the Omran Center for Strategic Studies, Shabab al-Sunna, from Dara’a, and Jaish al-Tawheed, from Homs, both joined the corps in mid-2018.

According to a pro-regime Lebanese newspaper, the 5th Corps was planned to incorporate the Desert Hawks and Aleppo-based Liwa al-Quds as the elite units of the corps while Hezbollah commanders would lead other units.62 None of this seems to have happened, but it again reveals Russia’s interest in not just integrating paramilitary militias (e.g. the Desert Hawks and Liwa al-Quds), but also in bridging the gap between the SAA high command and the foreign fighters of Lebanese Hezbollah. In all likelihood the Russian and SAA command will continue efforts to integrate pro-regime militias into the 5th Corps.

January 2017: In the month following the regime’s capture of Aleppo city, the Republican Guard created the new 30th Division.63 Not only did the 30th Division incorporate all Republican Guard units in Aleppo under a single nominal command, but it was also intended to integrate the paramilitary militias in the city into the Republican Guard structure. While the 30th Division likely exists more as an administrative unit than anything else at this time, this rebuilding effort was important enough to the regime that Maj. Gen. Ziad Ali Salah, the deputy commander of the entire Republican Guard and the overall military commander of the 2016 Aleppo offensive, was placed in charge of the 30th Division until November 2017, when his deputy, Brig. Gen. Malik Alia, took over.64 It is difficult to determine the exact structure of the 30th Division, in large part because it exists more on paper than in reality, but at the very least it appears to operate three special forces regiments and three brigades.65

Additional Republican Guard expansions are visible in the creation of new brigades and the co-option of several special forces and SAA units into Republican Guard units. The 123rd and 124th Brigades and their respective battalions, the 629th and 872nd, appear to have been formed between 2014 and 2015 and would later join the 30th Division. The 10th Division’s 18th Brigade, which participated in the fall 2016 Aleppo offensive, joined the new division by 2018. Meanwhile, the 47th and 147th Regiments and the 83rd Battalion started the war as special forces units before later joining the Republican Guard’s 30th Division. For a detailed history of the Republican Guard and how its formations have undergone changes between 2011 and 2018, see Syria's Republican Guard: Growth and fragmentation.

Late 2018: As major combat operations wound down in 2018, the SAA began a period of serious restructuring with the help of the Russian military. The SAA faces a massive shortage of tanks and armored vehicles after losing more than 2,322 over the course of the war.66 Furthermore, eight years of civil war appear to have convinced the regime that the biggest potential challenge to its survival is not a conventional war with Israel, but internal threats. Thus, in this current phase the SAA is being rebuilt as a largely motorized infantry army, one that is able to quickly deploy loyal soldiers to areas of insurgency or unrest across the country.67

Emphasis is also being placed on replenishing the SAA’s depleted ranks. According to one source, an SAA division today contains around 11,000 men total, including reservists and civilian employees.68 The 18th Division has only 4,000 men (active duty, reservist, and civilian), while the 1st Division likely has more than 11,000. Attempts to integrate loyalist militias have already been discussed, but the regime has also tried to pressure reconciled rebels and civilians in formerly opposition-held locales to join. Since 2017, but with a renewed push in the second half of 2018, reconciled rebels have been heavily recruited into the 7th, 9th and 10th Divisions as well as the 5th Corps. Other contingents of former rebels have been incorporated into the 8th Division (from Dara’a), and the 1st Division’s 61st Brigade (from Douma) and 171st Brigade (from Rastan). Initially, the 4th Division was meant to replenish its ranks with former rebels from Dara’a and al-Quneitra, however, following “internal disputes,” the division backed out and now many former rebels from these areas have joined the 105th Brigade of the Republican Guard.69

Reconciled rebel units remain in the south of the country for the most part as “they are not deemed trustworthy” and thus are either stationed in brigade headquarters or deployed around Dara’a and Damascus.70 However, several former rebels from the Damascus region serving in the 1st Division were killed during the May 2019 fighting in Hama and Idlib and ex-rebel anti-tank guided missile (ATGM) units within the 9th Division are reportedly being trained by the Russians in Jableh, Latakia.71 Furthermore, a large contingent of reconciled rebels have joined the 5th Corps’ 4th Brigade and are currently stationed in the Homs desert around Palmyra. According to one interview with a Palmyra NDF member currently stationed there, these ex-rebels are being sent on patrols around the ISIS-controlled region of Mount Bashiri and dying by the dozens every day. The source stated that “it's very suspicious that these guys get sent out in the desert with little support and they seldom return, and if they return, they get sent out again. Tactic seems to get rid of many of these reconciled rebels in this area.”72

Several reconciled rebel commanders in southern Syria began claiming in March 2019 that the Russians were attempting to create a new 6th Corps, which would be largely staffed by ex-rebels.73 Both the Omran Center for Strategic Studies and this author’s own interviews have corroborated these claims. Omran states in their report that the new 6th Corps will be centered around the 3rd Division, a middling SAA unit who has supported ex-rebel fighters in the northern Damascus countryside for some years.74 However, these attempts have reportedly faltered and are still in their very early stages.

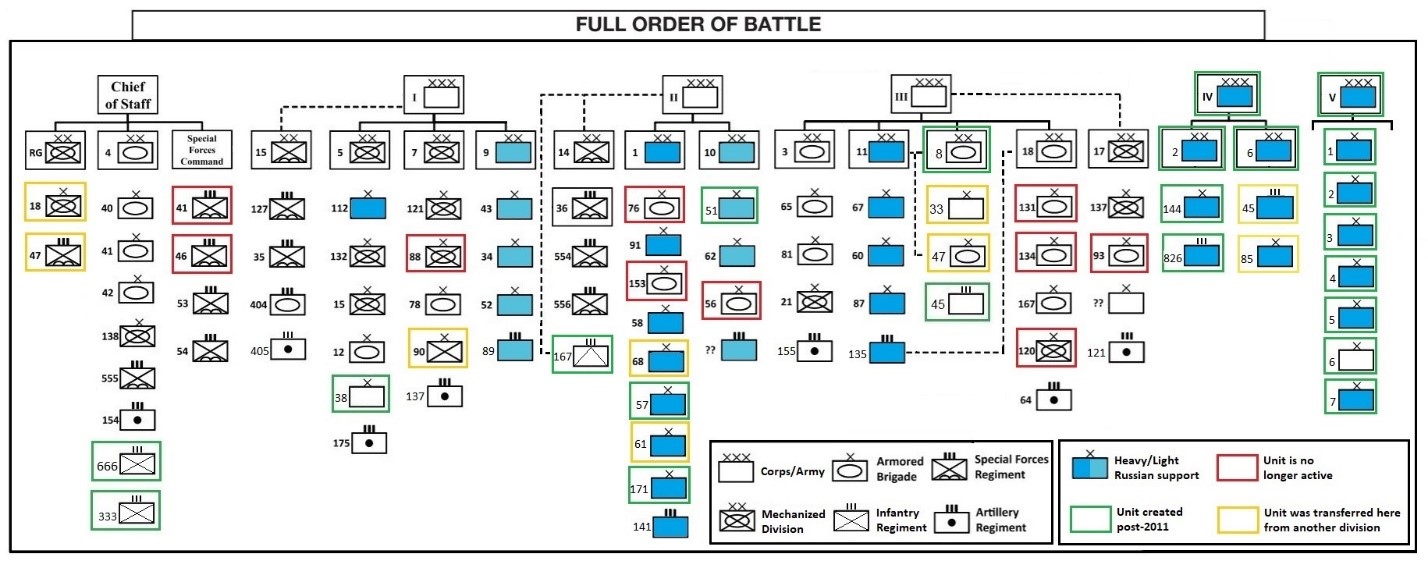

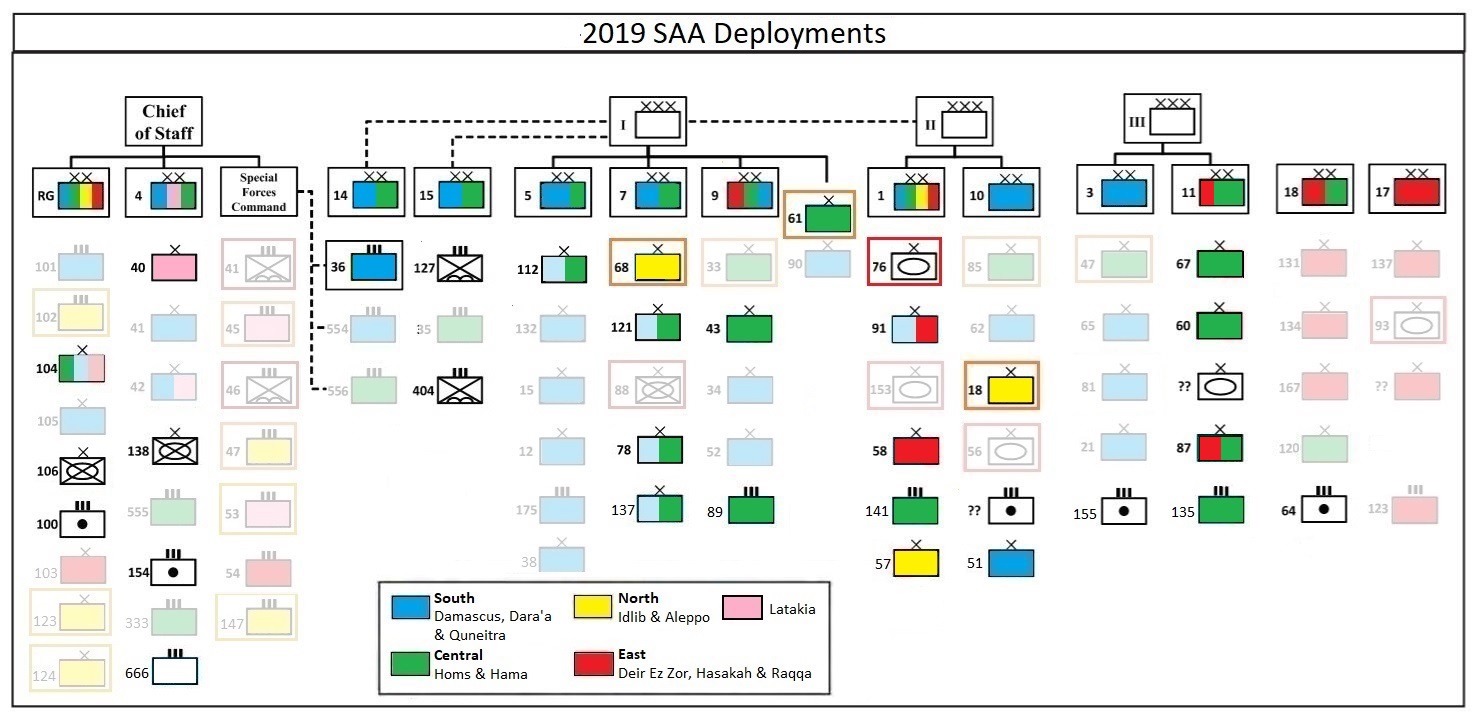

The following chart shows the SAA Order of Battle as of early 2019. All information was verified via pro-regime social media posts. It is entirely possible that some information is outdated and that other information is missing.

Russian military advisors have taken the lead in retraining and re-equipping several SAA divisions. The 1st, 9th, 10th, and 11th Divisions have all received Russian training and equipment in some form, with focus placed on the 1st and then the 11th Divisions. The 9th Division's current training is focused on educating the unit's new officers while the 10th Division's soldiers are being drilled on defensive tactics. This would indicate that these four divisions are viewed by Moscow and Damascus as “core” units to which limited resources are to be diverted. Importantly, all but the 10th Division has taken part in the Russian-led May 2019 offensive in Hama alongside the Tiger Forces, Liwa al-Quds, and local NDF — all trained and equipped by Russia as well.

Aside from these significant Russian-led efforts, the SAA has gradually reorganized its units as necessitated by conditions on the ground. The aforementioned “task-organizing” of units in the first years of the war meant that, by the middle of the war, many brigades and regiments had either been wiped out or had spent so long deployed far from their division headquarters that it made more sense to change their divisional affiliations. Therefore, the observed shifts in unit affiliation appear to have largely come about due to mid-war consolidation of units based on regional deployments in an attempt to strengthen logistical and command lines.

Beginning in late 2018, Syria’s new minister of defense, Maj. Gen. Ali Ayoub, initiated a new program to rebuild the “dead” units of the SAA with a focus on Special Forces and the Republican Guard.75 Some new graduates of Syria’s military academies are assigned to previously “dead” units — units that are either non-operational due to lack of manpower or which were made completely defunct at some point in the war. Here, the men are claimed to have the opportunity to “prove themselves” and gain quick promotions.76 The aforementioned 1st Brigade of the 4th Corps is one such unit. Currently, however, the focus of this strategy is on the 112th Brigade of the 5th Division, with plans to revive dead units from the Special Forces and Republican Guard soon. This claim is supported by the recent appointment of prominent generals as commanders and chiefs of staff for the Special Forces Command, Republican Guard, and 30th Division.77

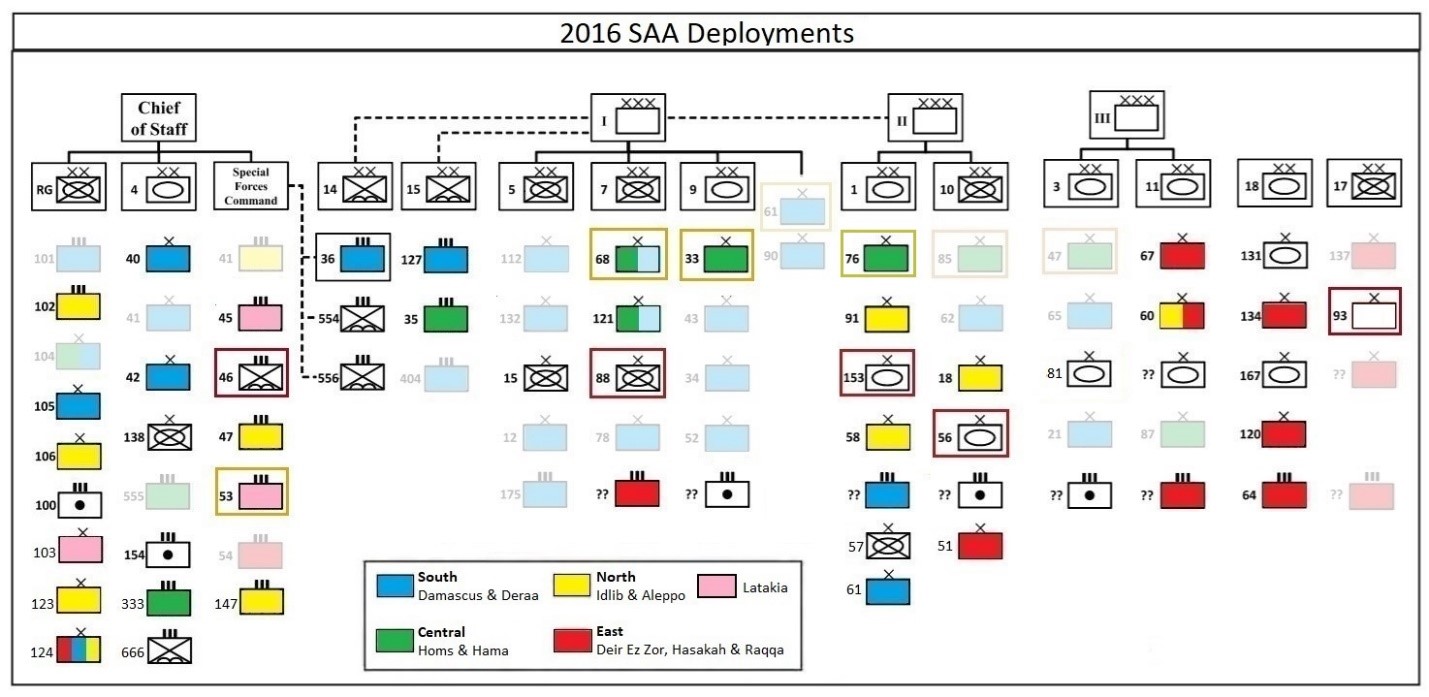

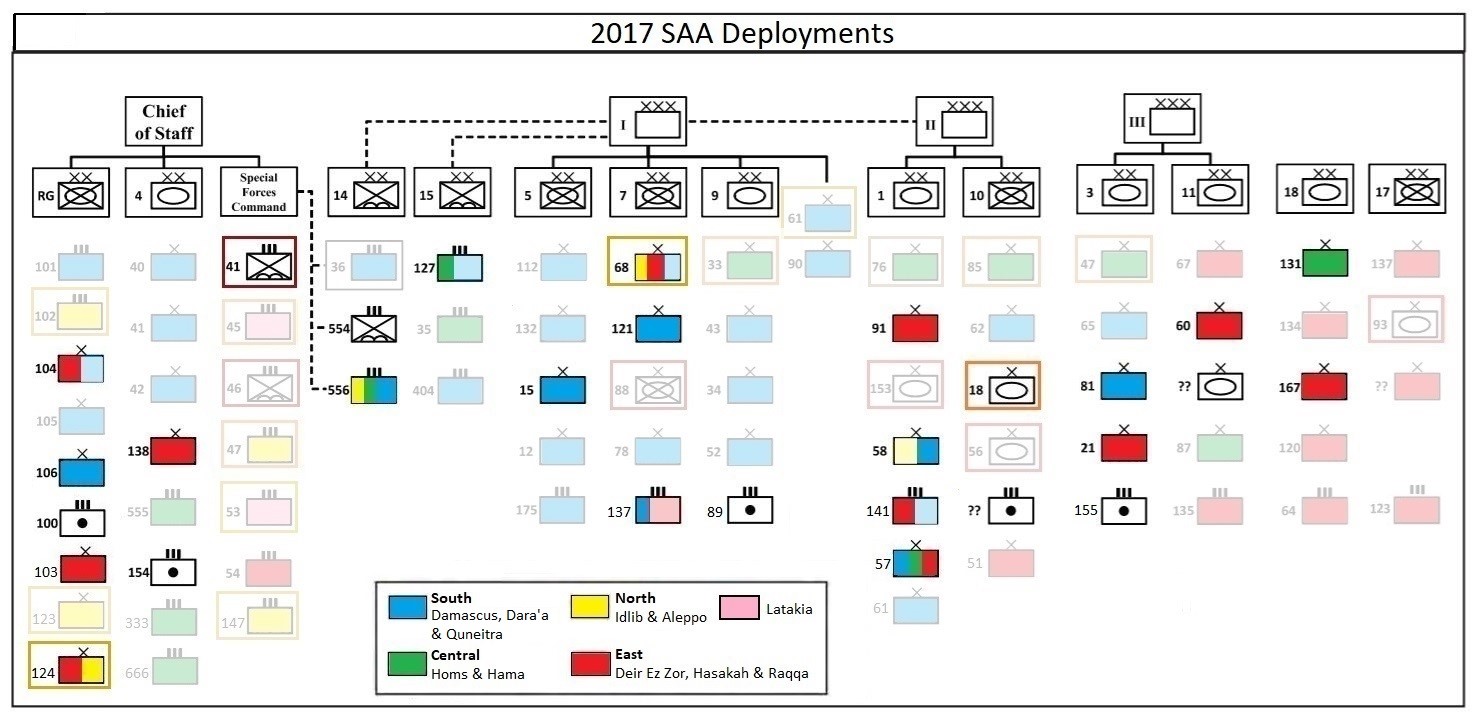

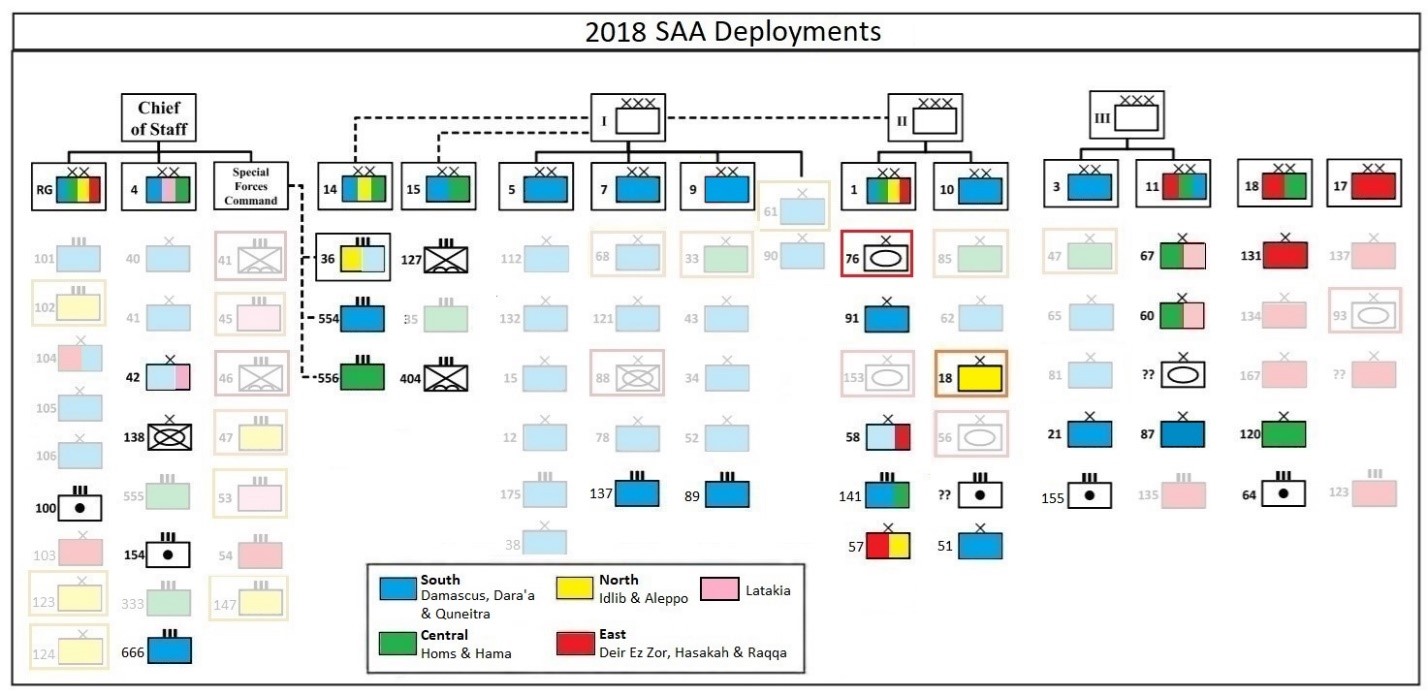

The following figures track unit deployment from 2016 to 2019 and are compared alongside Joseph Holliday’s figure of deployments in 2013.78 The brigades outlined in red no longer exist, while brigades outlined in orange have been moved to other divisions. For this data, only the original order of battle is used since new divisions and corps generally remained in the same geographic region. Faded units did not change their region of deployment from the previous year. The data shows a clear trend of divisions losing their brigades that had been deployed to fronts other than those where the bulk of the division was deployed.

While there are many conclusions to draw from the above figures, one of particular interest is the general region of focus the three corps did or did not have during the war. The 1st Corps was, upon its inception, intended to serve as the first line of defense against Israel and was thus stationed along the Golan and across Dara’a.79 This corps remained almost entirely deployed in Dara’a and Quneitra — its ‘home turf’ — despite losing many of its bases to the Syrian opposition. The 2nd Corps, however, was oriented toward Lebanon in a defensive arc around Damascus and the Qalamoun.80 While each of the corps’ divisions always maintained units in this region, many of their original components were spread out across the country, resulting in significant shrinkage of the 10th Division and expansion of the 1st Division (discussed below).

Lastly, the 3rd Corps was designed to hold the interior of the country.81 Its 3rd Division guarded the northern approaches to Damascus while the 11th Division was tasked with securing central Homs. This explains why, by mid-war, the 11th Division was almost fully committed to Homs and Deir ez-Zor and the 3rd Division was split between Damascus and the east. This orientation also helps explain why the 17th and 18th Divisions, both of which would see significant deployments in central and eastern Syria, would later be incorporated into the 3rd Corps. The data would therefore seem to support Holliday’s argument that Damascus resisted deploying the bulk of the SAA far from their bases, but also appears to indicate that, when deployed at length, they made a conscious effort to keep their divisions and brigades within their original areas of operation.

The following sections examine each corps of the SAA as it stands today. As with the above deployment data, the information below comes from pro-regime Facebook posts discussing unit deployments and affiliations. All information comes from multiple corroborating posts, as well as an interview with a Syrian loyalist connected to the military. As with any project of this scale, there are bound to be omissions. Some units are still in flux, moving between divisions, or in the process of being resurrected. Therefore, the following sections should be viewed as a working guide for the general state of the SAA today.

(Photo credit: STRINGER/AFP/Getty Images.)

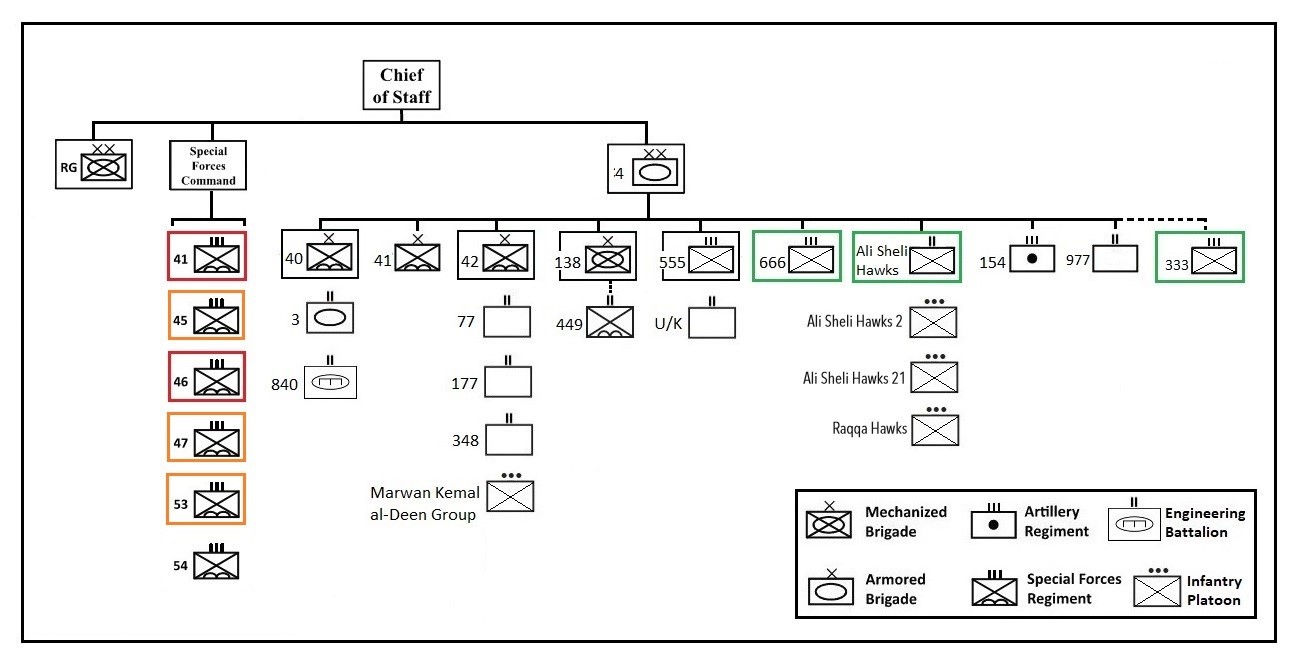

Prior to the outbreak of the war, the SAA had three semi-independent commands along with its main three corps. These units technically fell under the command of the chief of staff, although each command and its component brigades and regiments appeared to generally operate independently from each other throughout the war. The chief of staff position itself remains empty since the former chief, Ali Ayoub, was promoted to minister of defense.82 The current deputy chief of staff is Wasel al-Samir, the commander of the 5th Division.83

Special Forces

The Special Forces no longer exists in any meaningful way as its original regiments have either been decimated or incorporated into other formations. The command initially oversaw six regiments: the 41st, 45th, 46th, 47th, 53rd, and 54th. The 41st Regiment ceased to exist after losing too many men and the 46th Regiment has been demobilized after sustained losses.84 The regiment maintains an office in Damascus but most of its men have reportedly returned to civilian jobs. The 54th Regiment, which also suffered very heavy casualties, has been largely silent since the complete government recapture of Homs, when most of its surviving members were incorporated into the Air Intelligence administration in the city, with the remainder stationed in Qamishli.85

The 45th Regiment was incorporated into the 4th Corps’ 6th Infantry Division sometime between October 2015 and late 2018. The unit was tasked with holding the Latakia front following its defeat in Jisr al-Shoughour, Idlib, in May 2015 and thus fell under the regional purview of the Russian-backed 4th Corps. By May 2015, the 47th Regiment and its affiliated battalions were being referred to on social media as “Republican Guard” units, likely a result of the units’ continued deployment in Aleppo and the regime’s multi-year attempt to consolidate Aleppo-based forces under a single Republican Guard command — a task that ultimately culminated in the formation of the 30th Division. The 53rd Regiment was reportedly one of the founding units upon which the Tiger Forces were built and formed the core of the force in its first year.86

4th Division

While the 4th Division is often referred to as “elite,” it can more accurately be described as a collection of loosely affiliated units built around a core of well-equipped armored battalions. For example, the Hama-based Ali Sheli Hawks Regiment was originally formed as a component of the Tiger Forces. However, the group was forced to find new patrons after one of its commanders, Jalal Mubayed, was accused of raping the daughter of another commander of the Tiger Forces and other members of the group held pro-government citizens for ransom in their headquarters in Tell Salhab.87 The unit ended up finding support within the 4th Division by the end of 2017, a change clearly reflected in the militia’s social media posts. These units enjoy the privilege of association with Bashar al-Assad’s brother, Maher, who reportedly remains in command of the division and regularly holds meetings with his staff, but is not believed to lead the division on a day-to-day basis.88 Some components of the division have historically been better equipped than most pro-government units.89

The 4th Division, along with units of the Republican Guard, formed the core for offensive operations in Damascus and Dara’a for much of the war.90 The division heavily recruits from Damascus, as well as pulling many officers and enlisted men from Latakia and Tartous. However, martyrdom reports of men belonging to the division reveal that it has, at a minimum, recruits from every governorate aside from Hasaka and Raqqa, although it is entirely possible that men from these regions also fight in the division. According to one source, the 4th Division has failed to maintain the quality of soldiers it once fielded due to significant battlefield attrition. The division lost many experienced officers and runs its own training program, meaning it is not adopting any practices brought in by Russia or incorporated by other SAA units.91 They are now reportedly worse than the 9th Division.92

The 4th Division’s 555th Special Forces Regiment has been stationed on the Kernaz-Mughayr axis of north Hama since at least 2013. This unit participated in repelling the failed opposition attack on Kernaz in March 2018. The 42nd Armored Brigade, also known as “the Ghaith Forces” after its commander, Col. Ghaith Dalah, has been stationed in the Sahl al-Ghab region of north Hama since at least Sept. 26, 2018. The brigade operates across the Latakia mountains and Sahl al-Ghab with a base in Jurin. The 42nd Brigade has the heaviest media presence of all 4th Division units and appears to be the premier brigade within the division.

The only explicit connection between the 449th Battalion and 138th Brigade comes from a February 2012 post by a now-defunct pro-opposition page claiming to “identify” members of the regime security forces. However, both units were deployed to the Uqayribat pocket in East Hama/East Homs in the fall of 2017. By late 2017, a new 666th Infantry Regiment operated under the 4th Division name.

There is no explicit mention of the 154th Artillery Regiment after 2016, although it is clear that the 4th Division controls and deploys artillery units extensively. In May 2018, the 4th Division unveiled its newest version of the “Golan” improvised rocket-assisted mortar model, the Golan 1000. The 4th Division also employs Golan 65, 250, 300, and 400 models.93 A May 2012 post by a pro-opposition Syrian claimed that the 154th Regiment consisted of the 403rd, 408th, and 409th Battalions. However, no other posts could be found confirming the existence of these units. An August 2015 post by a pro-regime Syrian page showed a memorial for 114 martyrs from the 154th Regiment.

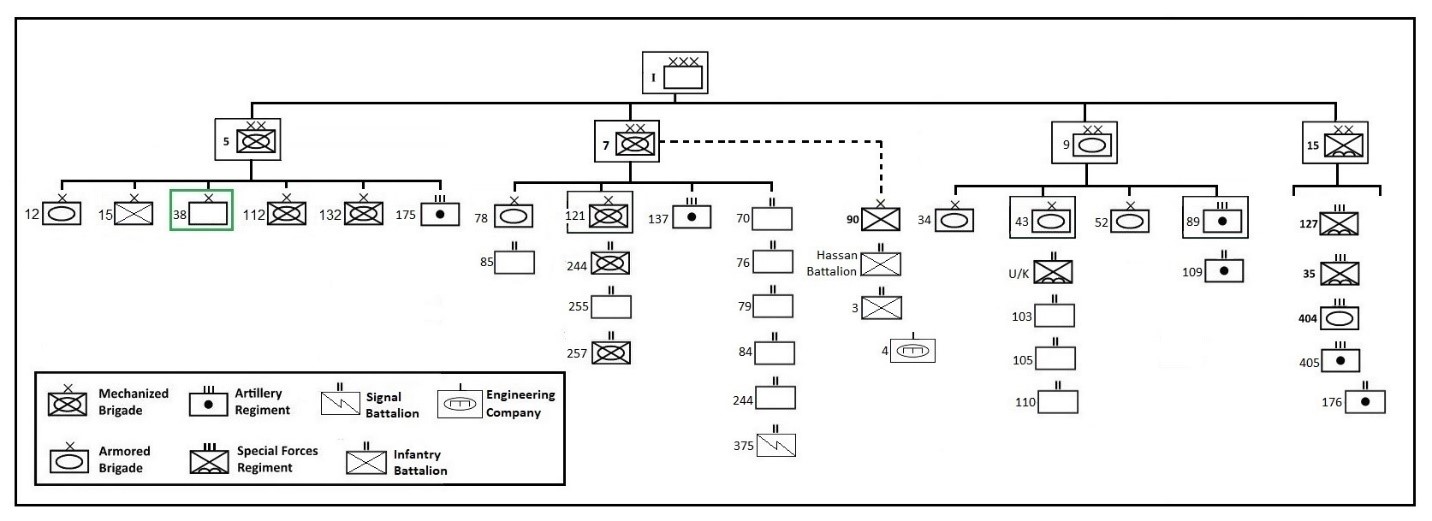

5th Division

The 5th Division originally consisted of three mechanized brigades — the 112th, 132nd, and 15th — and the 12th Armored Brigade and 175th Artillery Regiment. All of these units appeared to have remained intact and under the division’s command over the course of the war. Additionally, the division now seems to be associated with the 38th Brigade, a unit based out of the town of Sayda, just east of Dara’a.94 The 38th Brigade does not appear on the Institute for the Study of War order of battle but did indeed exist prior to the war. In all likelihood it is a missile defense brigade, as it has been the target of Israeli airstrikes and some loyalist posts have referenced “rocket battalions” operating out of it. The brigade’s base was captured by rebels in March 2013 and held until the spring 2018 regime offensive recaptured all of the south.95

This is the only division to remain almost entirely within one region for the whole war. Its bases stretch from east to west across the middle of Dara’a Governorate and as such the division was, for the most part, tasked with holding Dara’a. However, the 12th Brigade briefly fought in the neighboring Suwayda Governorate in 2017 and the 15th Brigade was deployed in Baba Amr, Homs, in early 2012. Furthermore, a “Force Commandos” unit of the 5th Division participated in the fighting around Abu Dali, Idlib, in late 2017 and early 2018, although this was likely a small unit.

7th Division

The 7th Division lost at least four unit commanders during the course of the war: Maj. Gen. Abdelrahman Ibrahim, commander of the 88th Infantry Brigade, killed in Jabal Zawiya, Idlib on June 24, 2013; Brig. Gen. Sam Sultan, the next commander of the 88th Infantry Brigade, killed in Kafraziba, Idlib in late July 2014; Brig. Gen. Muheil Ahmad, commander of the 68th Mechanized Brigade, killed in Beit Tema of rural Damascus on Aug. 9, 2014; and Brig. Gen. Rakan Diab, commander of the 137th Artillery Regiment, killed in Quneitra on July 15, 2018.

The 68th Brigade moved from the 7th Division to the 1st Division sometime in 2015. However, many Facebook posts made by both members of the 68th Brigade and by a 7th Division page continued to refer to the brigade as a component of the 7th Division through 2017. Elements of the brigade also deployed alongside the 7th Division’s 137th Artillery Regiment to both Deir ez-Zor and then Beit Jin in the second half of 2017. The 241st Mechanized Battalion of the 68th Brigade was among the first units deployed to Deir ez-Zor in 2011. The remnants of the battalion would remain here until 2017.

The 88th Brigade, which had long been stationed in north Hama/Idlib, moved to the newly created 6th Division in early 2015 but suffered significant losses during the opposition’s spring 2015 offensive. One source claimed that “The 88th Brigade has very few survivors. … Those who survived were killed at other fronts after that disaster.”96 The rest of the 7th Division has almost exclusively fought in south Syria since at least the end of 2017, although elements of the 137th Artillery Regiment were deployed in Deir ez-Zor in March 2017.

Commanders of the 90th Brigade have been regularly pictured alongside 7th Division officers since the summer of 2018, implying at least some level of administrative ties between the formerly unaffiliated 1st Corps Brigade. On May 10, 2019, the SAA high command appointed Maj. Gen. Hussam Luka to oversee the restructuring of the 7th Division. According to one source, Luka is seeking to turn the remaining two brigades of the 7th Division into “elite brigades” as well as move the division’s headquarters from Damascus to Aleppo as he “sees Damascus as the graveyard of the SAA, and he has good connections to Aleppo.”97 Luka was head of the Homs Political Security branch from 2010 until 2016, when he became assistant director for state security in Damascus. In November 2018, he was again promoted to director of the entire Political Security Directorate of Syria. Luka has been on the EU sanctions list since 2012 and is accused of torturing those in his custody.98

9th Division

The 9th Armored Division originally contained the 33rd, 43rd, and 34th Armored Brigades, the 52nd Mechanized Brigade, and an unknown artillery regiment. The artillery regiment has since been identified as the 89th Regiment. The 33rd Brigade was a foundational unit of the newly formed 8th Division and thus has no more ties to the 9th Division. Like the 5th Division, the 9th has by and large remained in the south since 2014. While the division was almost exclusively deployed in Dara’a, all of its components sent units to the various Damascus and Suwayda offensives in the second quarter of 2018. For a short period in 2018, the 9th Division was the focus of Russian rebuilding efforts. The division received Russian training and the bulk of reconciled fighters from Quneitra.99 However, by the start of 2019 the Russian program of training and rebuilding the 9th Division had largely ended as the focus shifted to the 1st Division.100 Since then, the 9th has sought new areas of recruitment but retained an emphasis on integrating ex-rebels. All that remains of the Russian program are a few ex-rebel anti-ATGM units that are reportedly being trained by the Russians in Jableh, Latakia.101

At least two 9th Division battalions moved to the Hama frontlines in 2019. A soldier from the 103rd Battalion, 43rd Armored Brigade, 9th Division posted pictures on Jan. 5, 2019 of a convoy consisting of BMPs, main battle tanks, and Gvozdika self-propelled artillery going “to the countryside of Hama.” A video posted on Jan. 16, 2019 shows Syrian Minister of Defense Maj. Gen. Ali Abdullah Ayoub meeting with members of the 9th Division and 5th Corps' 3rd Brigade in north Hama, including 103rd Battalion Commander Brig. Nizar Fandy. A second video posted on Jan. 25, 2019 shows the commander of the 9th Division, Maj. Gen. Ramadan Ramadan, meeting soldiers of the division in north Hama.

These units took part in all major military operations in 2018. Then-Col. Nizar Fandy and his battalion were lauded for their role in the government’s defense of Harasta, East Ghouta, in January 2018. The brigade also fought in the Hajar al-Aswad offensive in May and again in the Safa Volcano offensive over the summer.

15th Special Forces Division

The 15th Special Forces Division was one of two special forces units on which the regime heavily relied in the early years of the war due to its higher degree of training, equipment, and loyalty to Damascus. However, this reliance meant the division's component regiments suffered heavily, and by 2017 it became rare to find references to specific 15th Division units. According to a 2019 interview by the author, “The 15th has been smashed to pieces and the remnants are located in Dara’a city for the most part.”102 The unit no longer recruits new members.

The 127th, 404th, and 405th regiments have spent the majority of the war fighting in Dara'a and Suwayda, while the 35th Regiment remains stationed in Idlib, participating in the defense of Jisr al-Shoughur in March 2015. A 15th Division fighter was reported killed in Jadedah, northwest of Muhradah, Hama, on March 11, 2019. He likely belonged to the 35th Regiment.

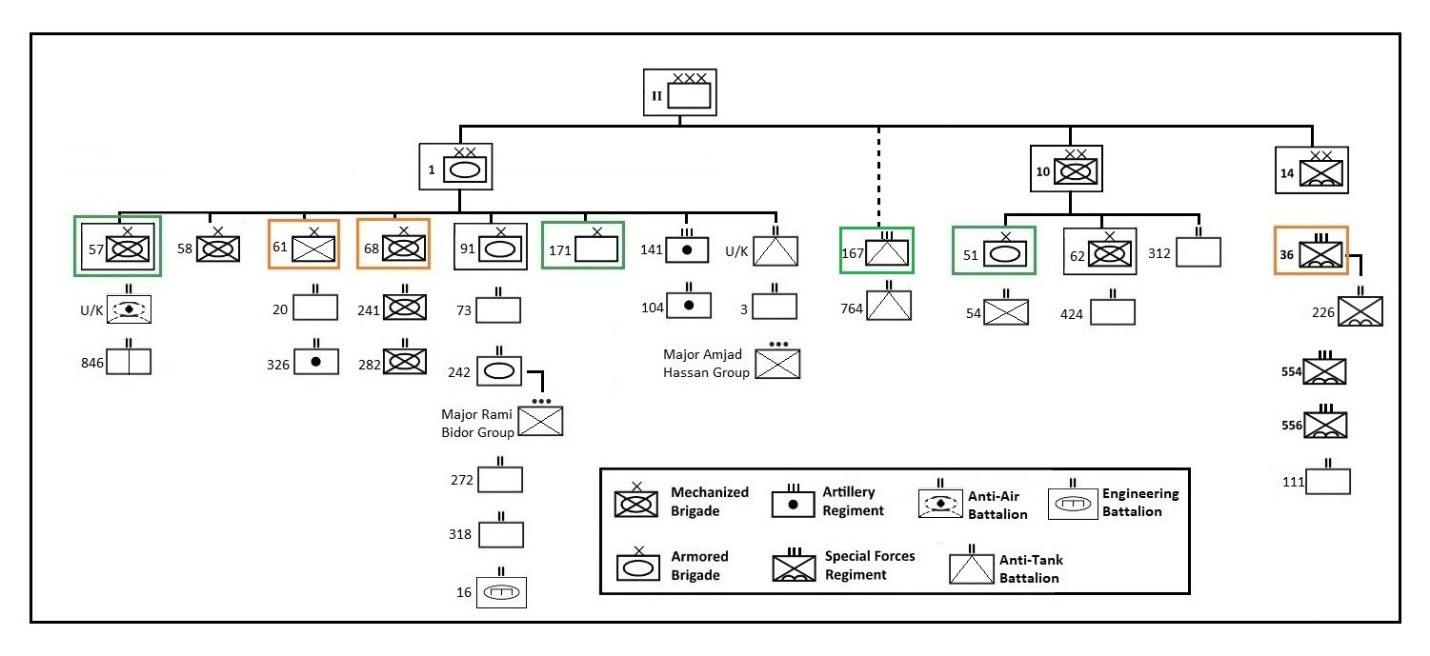

1st Division

The 1st Division initially consisted of the 58th Mechanized, 76th Armored, 91st Armored, and 153rd Armored Brigades and was thus an armored division. The 91st Brigade remains the only self-declared armored unit today. The 76th Armored Brigade briefly joined the newly formed 6th Division in 2015, although it is now defunct.103 Following the regime’s capture of the last opposition pockets in Damascus, the 153rd Armored Brigade was placed entirely under the command of Military Intelligence Branch 235, also known as the Palestine Branch, which is tasked with overseeing the newly reconciled areas of the city.104 In 2015, the 68th Mechanized Brigade was moved from the 7th Mechanized Division to the 1st Division. The 61st Infantry Brigade (originally an independent brigade under the 1st Corps), the 57th Mechanized Brigade (formed in 2015), and newly formed 171st Brigade (which first deployed in late May 2019 to Hama) all joined the 1st Division at some point during the war. Lastly, there appears to be a 167th anti-tank regiment that formed around 2014. This regiment has at times been linked to the 1st Division, 11th Division, 18th Division, and 2nd Corps. For now, it has been included as part of the 2nd Corps.

Today, the 1st Division is the largest division on paper and its reconstitution has clearly been prioritized since 2015 with a renewed push beginning in the latter half of 2018. In September 2018, pictures came out of Russian officers training a company of soldiers belonging to the 68th Mechanized Brigade in the 1st Division’s armored vehicle training center in Harjala, south Damascus.105 On Dec. 25, 2018, both the 68th and 57th Brigades deployed alongside Russian forces in the western countryside of Manbij, Aleppo, where the two groups stationed themselves in between Turkish-backed opposition forces to the west and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Manbij city.106 The 61st Brigade opened a recruitment office in Douma, Damascus, in mid-2018, from which it recruits former opposition members in the area, while the 171st Brigade recruits heavily among Republican Guard defectors who fought in the Rastan region of Homs and surrendered in early 2018.107 According to the Omran Center for Strategic Studies, the 61st Brigade has been “entirely restored” by the Russians and “is the largest and most important combat brigade in the Syrian army.”108

The 1st Division’s 61st Infantry Brigade announced on Jan. 1, 2019 that it was redeploying to reef Hama. A post on February 4 confirmed this new deployment. It was joined by the division’s 141st Artillery Regiment as early as January 26. The 61st Brigade has historically fought in Dara’a and Quneitra, while the 141st Regiment appears to have been split between the Deir ez-Zor-Homs and the south Damascus fronts.

10th Division

The 10th Division initially consisted of the 18th Mechanized, 62nd Mechanized, 58th Armored, and 85th Mechanized Brigades and thus was a mechanized division. The 58th Brigade has not existed in any meaningful way since at least late 2016 and the 85th Brigade was moved to the newly formed 6th Division in 2015. The 51st Armored Brigade was formed at some point after 2011 as a new armored unit under the command of the 10th Division. The 18th Brigade had moved to the Republican Guard by late 2018. Its last known deployment was in Aleppo during the fall of 2016.

This is one of the smallest divisions in the SAA today and has been largely gutted, possible due to continued deployments fighting ISIS in Deir ez-Zor, Homs, South Damascus, and reef Suwayda. The division is headquartered in the town of Qatana in southwest Damascus where it undertakes most of the urban development projects, including electrical and road repairs and waste cleanup. It is one of several divisions recruiting heavily among former rebels across southern Syria. Some sources claim that elements of the division are currently being trained by Russian officers in Safita, Tartous.

14th Division

The 14th Special Forces Division appears to have remained wholly intact throughout the war, although it had limited deployments for many years following heavy losses in the early part of the war and no longer recruits new members.109 Both the pre-war and current division consists of the 36th, 554th, and 556th Regiments. However, according to one source, the 36th Regiment has long been attached to the Tiger Forces and only operates within the divisional structure when deployed in southern Syria.110 Deployment history for these units is difficult to track, as the unit’s main Facebook page reporting its martyrs disappeared in early 2018. However, the 36th Regiment was consistently deployed in Aleppo with one unit, the 224th Battalion, stationed in Jabal al-Sheikh, Quneitra. The 554th Regiment was deployed in Harasta and then East Ghouta, Damascus, in early 2018. The 556th Regiment was deployed in Idlib in 2012, 2014, and 2017 before also reinforcing Harasta, Damascus in January 2018.

"Eight years of civil war appear to have convinced the regime that the biggest potential challenge to its survival is not a conventional war with Israel, but internal threats. Thus, the SAA is being rebuilt as a largely motorized infantry army, one that is able to quickly deploy loyal soldiers to areas of insurgency or unrest across the country."

3rd Division

The 3rd Division initially consisted of the 47th Armored Brigade, 65th Armored Brigade, 81st Armored Brigade, and 21st Mechanized Brigade along with an unknown artillery regiment — possibly the 155th. The 47th Regiment was the only unit of the division to be deployed outside of Damascus in the early years and soon became associated with the 11th Division before eventually being brought under the command of the 8th Division. For the most part, the rest of the division remained in Syria’s south: The 65th Brigade manned the fronts around Eastern Ghouta, Damascus, while the 81st Brigade — referred to as both a “special tasks” and “armored” brigade — operated in the Damascus countryside. However, one unit (possibly the 21st Brigade) deployed to Deir ez-Zor in 2016 and the 21st Brigade lost at least one fighter in combat around Tanf, Homs in June 2017 and Suwayda in June 2018.

The 3rd Division played a central role in creating and supporting the pro-government Qalamoun Shield Forces militia, consisting of loyalist and reconciled rebels in the north Qalamoun area of Damascus in 2015.111 The division has been inactive since the mid-2018 offensives to clear the opposition pocket in East Ghouta, Damascus, and the ISIS pocket in north Suwayda. Since then, the bulk of the 3rd Division’s units have returned to their respective bases on the outskirts of Damascus.112

8th Division

The 8th Division is a post-2011 creation intended specifically to hold the north Hama front. Formed around mid-2015 during the opposition’s Idlib offensive, the division was designed to unify individual brigades that had either suffered significant losses in south Idlib/north Hama or whose division affiliations had weakened after years of fighting. The unit brought together the 33rd Brigade from the 9th Division and the newly created 45th Regiment. However, both the 6th and 8th Divisions simultaneously claim to operate a “45th Regiment,” although only the 6th Division refers to it as a “special forces” unit. It is unclear if these are two separate regiments or if they have a shared command. Lastly, the 47th Brigade, originally a 3rd Division unit, now appears to be shared by both the 11th and 8th Divisions. The division is at times referred to as a “twin division” of the 11th Division and likely comes under some administrative control of said division due to the fact that the 11th Division’s 47th Brigade is based in north Hama.

The entire 8th Division has been deployed in Hama since 2015 while its component units have been there even longer. The 33rd Brigade currently has units stationed both along the northern most points of the Sahl al-Ghab on the Sirmaniyah-Ziyariah axis as well as just north of Suqaylabiyah.113 The brigade’s commander, Brig. Gen. Yahya Baloush, was killed in north Hama in May 2017. The 45th Regiment is just south of this, sharing a base with the 4th Armored Division in Jurin. The 47th Armored Brigade is currently deployed on the Taybat al-Ism-Qahira axis. On May 28, 2019, 17 members of the 33rd Brigade were reported killed in fighting in Kafr Nabudah, north Hama. Many of the men were former opposition fighters from Dara’a who had surrendered to the regime and were “given” to the 8th Division in mid-2018.114 The division is also reportedly well-known for the diverse geographic make-up of its fighters — it is one of the only divisions with recruitment offices in Hasakah and Qamishli.115

11th Division

The 11th Division has, since the start of the war, manned central Syria. Interestingly, its brigades have been separated for nearly the entire civil war, yet they retained their divisional affiliations. The division’s 87th Mechanized Brigade and its 74th Battalion have been stationed along south Idlib and north Hama since at least 2012. This brigade reportedly belonged to the newly created 4th Corps for a short period of time before transferring back to the 11th Division.116 These units have held the highly contested Suran-Masasana axis since at least 2016. Several members of the 87th Brigade died in the March 3, 2019 raid on the checkpoint here. Meanwhile, the 60th and 67th Brigades and the 135th Regiment have mostly fought on the eastern edges of the Homs Governorate, particularly around Palmyra as well as throughout Deir ez-Zor. The unknown brigade identified in Holliday’s report appears to be the 47th Brigade, although this unit also appears under the command of the newly-formed 8th Division. The 11th Division units stationed in north Hama were receiving Russian advising and support by March 2019.117

The 11th Division has lost 10 of its top officers since 2015 and “has very few experienced heads left, [it is] mostly staffed with fresh guys.”118 On July 15, 2015 the overall commander of the 11th Division, Maj. Gen. Mohassan Makhlouf, died fighting ISIS in Palmyra. The division lost its next overall commander on June 9, 2018 in Boukamal, Deir ez-Zor. The 47th Brigade has lost four of its commanders, all in northern Hama, first in December 2013, then November 2015, then September 2016, and lastly in October 2017. The chief of staff of the 60th Brigade died on Aug. 10, 2017 in Badia and the chief of staff of the 67th Brigade died of wounds received on Dec. 20, 2017 in Deir ez-Zor — these are the brigades’ only generals lost during the war. The 87th Brigade lost its commander in Maardes, north Hama on Sept. 1, 2017 just two weeks after the commander of the brigade’s 74th Battalion was killed on the northern Rastan front. A May 14, 2019 post by the division’s official Facebook page also referenced “dozens” of killed battalion and company commanders. According to one source within the division, the unit had 11,000 members in November 2018, including reservists and civilians, of which approximately 8,800 were active duty soldiers.119

17th Division

Originally a reserve-armored division stationed in Raqqa, the 17th Mechanized Division appears to have some administrative ties to the 3rd Corps. As a reserve division, this unit was reportedly only at half-strength before the war even started.120 The division has spent the entire war in the east of the country and will likely remain stationed in Deir ez-Zor, Raqqa, and Hasaka. Several units from both the 11th and 3rd Divisions regularly fought alongside the 17th Division in Deir ez-Zor and east Homs. The 17th Division’s 93rd Brigade and 121st Regiment bases were overrun by ISIS during the group’s July-August 2014 offensive across eastern Syria. The author has found no reports of the 93rd Brigade since then, and in 2017, a pro-government news page claimed that more than 400 members of the 93rd Brigade were still missing, along with another 600 members of the division.121 The unknown third brigade identified in the Institute for the Study of War’s 2013 report still remains unknown, as no additional brigade numbers could be confirmed by the author.

18th Division

The 18th Division spent the first two years of the conflict fighting in the Hama countryside before being nearly entirely redeployed to eastern Syria, where it has largely remained. It appears that the bulk of the division will be permanently stationed in the east to bolster the remnants of the 17th Division. By 2015, elements of the 18th Division were being referred to as “3rd Corps,” indicating that the previously independent armored unit had come under the administration of the corps. This reflects the broader trend of 3rd Corps divisions and brigades bearing the brunt of the SAA’s fight across eastern Syria.

The traditionally strong ties between the 18th Divisions and the 3rd Corps’ 11th Divisions have only grown stronger over the course of the war. There are reportedly discussions on creating a “shared” brigade between the 11th and 18th Divisions, much like how the 47th Brigade is affiliated with both the 8th and 11th Divisions.122 Additionally, a November 2018 post by the 11th Division’s main Facebook page referred to that division’s 135th Artillery Regiment as belonging to the 18th Division. For its part, multiple posts in 2015 and 2016 implied a connection between the 18th Division’s 64th Artillery Regiment and the 11th Division. It is likely that these artillery units have been shared between the divisions as needed, since the bulk of both divisions manned the same fronts for much of the war.

On paper, the division remains entirely intact from its 2011 structure. However, by 2015, the division had lost half of its men, mostly to fighting against ISIS in central and eastern Syria. As of November 2018, the division consisted of only 4,000 men — including reservists and civilian employees — largely concentrated within the 167th Brigade.123 All other brigades within the division are essentially non-operational. While members of the other brigades have periodically posted on social media about deployments in the southern Badia, it is likely that these are simply the remnants of those brigades brought in under the 167th.

Central to the 4th Corps were the newly formed 2nd and 6th Divisions. Interestingly, it appears that the 45th Special Forces Regiment, formerly an independent unit under the command of the Special Forces branch of the SAA, was incorporated into the 6th Division by late 2018. The 45th Regiment had remained in Latakia after retreating from Jisr al-Shoughur, Idlib, in May 2015. Complicating matters is the fact that both the 6th and 8th Divisions simultaneously claim to operate a “45th Regiment,” although only the 6th Division refers to it as a “special forces” unit. It is unclear if these are two separate regiments or if they have a shared command.

The 2nd Division’s 144th Coastal Brigade and 826th Regiment are both stationed on the Latakia axis. The 6th Division’s 45th Special Forces Regiment also mans the Sirmaniyah axis, where it lost 23 men in a November 2018 opposition raid.124 The division’s 85th Brigade is stationed somewhere in the Sahl al-Ghab. In December 2018, members of the 45th Regiment posted on Facebook asking the government to give them more leave time from the frontline so they could visit their families.

According to the Omran Center for Strategic Studies, “the 4th Corps personnel was drawn from members of the Syrian army, its staff, and veterans, or those who left the army for one reason or another, without the need for recruitment campaigns.”125 At its peak, the corps consisted of nearly 12,000 fighters.126 However, the project was judged a failure following several poor performances against opposition forces in Latakia, and in December 2016 Russia tried again by creating the 5th “Storming” Corps. The 5th Corps also integrated loyalist militias — primarily those operating under the NDF banner — alongside volunteers and a large contingent of men who had previously avoided conscription.

In their May 2019 report, the Omran Institute for Strategic Studies estimated that the 5th Corps numbered 15,000 men.127 Units within the 5th Corps have remained on garrison duty around Hama and Idlib, while other units have fought in East Hama, Deir ez-Zor, and Damascus. It appears that between mid-2018 and January 2019, most of the deployed 5th Corps units returned to north Hama/east Idlib. However, the corps’ 7th Brigade remains in Deir ez-Zor.

The 1st Brigade has a small social media footprint. It currently contains one known battalion after the 79th Battalion was transferred from its command to the 6th Brigade in early 2018. The brigade spent most of its life fighting ISIS in the desert around Palmyra and Deir ez-Zor. However, at least some units of the brigade redeployed to north Hama by May 10, 2019 to participate in the government’s operation there, evidenced by a 1st lieutenant belonging to the brigade killed on May 11, 2019.

The 2nd Brigade is currently deployed in north Hama between Kernaz and Halfaya (posts from a local reporter place the 2nd Brigade in Halfaya on Feb. 4, 2019 while a 2nd Brigade fighter checked in at Suqaylabiyah on Facebook on March 9). Personal photos and posts from a 2nd Brigade soldier claim that units from this brigade are responsible for the recent shelling of Lataminah and Kafr Zita in Idlib that have killed dozens of civilians.128

The 3rd Brigade operates in the north Hama-south Idlib axis stretching from Abu Dali north to unknown headquarters in Idlib. The 3rd Brigade’s chief of staff, Brig. Aktham Hussein, was reportedly injured in east Idlib on February 14. The commander of the 3rd Brigade, Brig. Nizar Khadr, was filmed alongside Syrian Minister of Defense Maj. Gen. Ali Abdullah Ayoub meeting with members of the 9th Division and 5th Corps in north Hama on January 16. This is reportedly the largest brigade in the corps, a claim supported by its larger social media footprint and regular presence of Russians alongside the brigade commanders.

The 4th Brigade is the weakest brigade of the 5th Corps. According to one source, it has the worst training and equipment and is currently being used as a garrison force in the Homs desert while other units are shifted to more important fronts.129 At its inception, the unit recruited heavily from Idlib, Homs, and Hama, although it now contains a large number of ex-rebels.130 The Omran Center for Strategic Studies claims that the previously unaffiliated Ba'ath Battalions have also joined this brigade.131

The 5th Brigade operates in north-east Idlib and possibly in the southern Aleppo countryside with a base in the city of Salamiyah, Hama. On March 10, an officer in the brigade claimed to be in Abu Dhuhur, Idlib. On Jan. 12, 2019, the 5th Brigade’s commander, Brig. Gen. Kheirat Kahla, met with the overall commander of the 5th Corps, Maj. Gen. Zaid Salah, in reef Idlib. Prior to this, the brigade had been deployed in Deir ez-Zor as late as Jan. 1, 2019. Portions of the brigade were redeployed to northwest Hama in early May to assist in the government’s Hama operation.

The 6th Brigade is the newest unit in the 5th Corps and only semi-affiliated with the overall command structure. The brigade was formed in February 2018 as “the Military Intelligence’s contribution to the project.” As such, it is commanded and funded by the Military Intelligence, not the Russians.132 Most of the brigade’s officers are members of the infamous Palestine Branch, responsible for some of the worst crimes in Assad’s prisons, and loyalists describe the unit as “brutal beyond compare.”133 While the unit spent most of its time gathering intelligence during the 2018 Damascus offensives, it redeployed in a frontline role in north Hama on May 9, 2019. The brigade is the smallest of the 5th Corps units with its two known battalions holding no more than 100 men each. The 79th Battalion transferred commands from the 1st Brigade to the 6th Brigade in early 2018 while the 86th Battalion is a resurrected unit made of mostly ex-Ba’ath Brigades fighters (the armed wing of the Ba'ath Party).134

The 7th Brigade and its 3rd Battalion appear to be permanently stationed in Deir ez-Zor where they both hold territory and conduct counter-insurgency operations against suspected ISIS hideouts alongside elements of the 17th Division.

Conclusion

Despite considerable attempts at rebuilding the SAA, the combat capabilities of the regime’s armed forces remain limited. New weapons and new recruits cannot fix a system of ingrained ineptitude and corruption in the officer class – the key segment of any effective modern military. Russia appears to be aware of this and has been significantly reshuffling the SAA high command. Since December 2018, there have been at least three groups of promotions and command changes, mostly focused on Republican Guard and Special Forces units. During this period more than 100 officers were moved into “critical positions” while officers close to Iran were marginalized.135 It is likely that Russia is seeking to put in place commanders that it believes will a) follow Russia’s vision of restructuring, and b) prove most capable of training effective fighting units.

Secondly, integrating reconciled rebels into the armed forces is an important first step to solidifying control over recently captured territory and mollifying potential sources of insurgency, but there is deep animosity and distrust between these men and loyalist recruits that will inherently hinder combat performance.136 Historically elite units like the 4th Division have suffered significant attrition and have been weakened by losses of their most effective officers, leaving inexperienced commanders in charge of low-quality recruits.137

Lastly, the recent Russian-led offensive against the rebel enclave of north Hama and Idlib is a stark reminder of these shortcomings. Despite nearly a year of rebuilding and retraining between this offensive and the last major offensive — the capture of East Ghouta in spring 2018 — the Russian-backed Syrian forces in Hama have shown an inability to adapt. There has been an over-reliance on so-called “elite” troops made up almost entirely of militias, supported in the rear by SAA units providing fire support and holding newly-captured ground all while relying on massive indiscriminate bombing campaigns. This strategy has led to a significant depletion in the currently deployed “shock” units and led to a stalled campaign, leaving SAA position vulnerable to relentless opposition ATGM strikes. Meanwhile, Damascus has allowed much of central Syria to be retaken by ISIS cells that operate with impunity in the Mount Bashiri region, ambushing and targeting regime convoys in the desert. The SAA may be rebuilt on paper, but it has only just begun its path toward becoming an effective fighting force that can successfully conduct operations without relying on overwhelming air support.

Endnotes

1. Jakub Janovský, “Seven Years of War — Documenting Syrian Arab Army’s Armoured Vehicles Losses,” Bellingcat, March 27, 2018, https://www.bellingcat.com/news/mena/2018/03/27/saa-vehicle-losses-2011….

2. Richard M. Bennett, The Syrian Military: A Primer, The Middle East Intelligence Bulletin, Vol. 3, September 2001, https://www.meforum.org/meib/articles/0108_s1.htm.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Anthony Cordesman, Aram Nerguizian, and Inout Popescu, Israel and Syria: The Military Balance and Prospects of War, (ABC-CLIO, 2008), 167.; Janovský, “Seven Years of War.”

6. Ibid., 167.

7. Anthony Cordesman, Arleigh A. Burk, and Aram Nerguizian, “The Arab-Israeli Military Balance,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 29, 2010, https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publi….

8. Both of the below charts come from: Joseph Holliday, “The Syrian Army: Doctrinal Order of Battle,” Institute for the Study of War, February 2013, http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/SyrianArmy-DocOOB.p….

9. Joseph Holliday, “The Assad Regime: From Counterinsurgency To Civil War,” Institute for the Study of War, March 2013, http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/TheAssadRegime-web….

10. “By All Means Necessary!: Individual and Command Responsibility for Crimes against Humanity in Syria,” Human Rights Watch, December 15, 2011, https://www.hrw.org/report/2011/12/15/all-means-necessary/individual-an…; Holliday, “The Assad Regime.”

11. Holliday, “The Assad Regime.”

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid; Charles Lister and Dominic Nelson, “All the President’s Militias: Assad’s Militiafication of Syria,” Middle East Institute, December 14, 2017, https://www.mei.edu/publications/all-presidents-militias-assads-militia….

15. Holliday, “The Assad Regime.”

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Kirill Semenov, “Syrian armed forces in the seventh year of the war: from the regular army to the volunteer corps,” Russian Council of International Affairs, May 17, 2017, https://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/analytics/the-syria….

19. Christopher Kozak, “An Army In All Corners: Assad’s Campaign Strategy In Syria,” Institute for the Study of War, April 2015, http://www.understandingwar.org/report/army-all-corners-assads-campaign….

20. Jonathan Tepperman, “Syria’s President Speaks: A Conversation With Bashar al-Assad,” Foreign Affairs Vol. 94, No. 2 (March/April 2015), https://www.questia.com/read/1P3-3606947211/syria-s-president-speaks-a-….

21. Christopher Kozak, “The Assad Regime Under Stress: Conscription and Protest among Alawite and Minority Populations in Syria,” Institute for the Study of War, December 15, 2014, http://iswresearch.blogspot.com/2014/12/the-assad-regime-under-stress.h….

22. Simon Tisdall, “Syrian president admits military setbacks, in first public speech for a year,” Guardian (London), July 26, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/26/syrian-president-public-s…; Maher Samaan and Anne Barnard, “Assad, in Rare Admission, Says Syria’s Army Lacks Manpower,” New York Times, July 26, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/27/world/middleeast/assad-in-rare-admis….

23. Lister and Nelson, “All the President’s Militias.”

24. Lucas Winter, “Syria’s Desert Hawks and the Loyalist Response to ISIS” Small Wars Journal, 2016, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/syria%E2%80%99s-desert-hawks-and-….

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.

27. Suadad al-Salhy,” Iraqi Shi'ite militants fight for Syria's Assad,” Reuters, October 16, 2012, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-crisis-iraq-militias/iraqi-shi….

28. Tobias Schneider, “The Fatemiyoun Division Afghan Fighters In The Syrian Civil War,” Middle East Institute, October 2018, https://www.mei.edu/publications/fatemiyoun-division-afghan-fighters-sy….

29. Ibid.

30. Anne Barnard, “Hezbollah Commits to an All-Out Fight to Save Assad,” New York Times, May 25, 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/26/world/middleeast/syrian-army-and-hez….

31. Joseph Daher, “Three Years Later: The Evolution of Russia’s Military Intervention in Syria,” Atlantic Council, September 27, 2018, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/syriasource/three-years-later-the…

32. Fadi Adleh and Agnes Favier, “Local Reconciliation Agreements in Syria: A Non-Starter for Peacebuilding” European University Institute, June 2017, http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/46864/RSCAS_MED_RR_2017_01.p…; “In A Syria Suburb Cleared of Rebels, A Gradual Return to Everyday Life,” NPR, December 25, 2016, https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2016/12/25/505304239/in-a-syrian….

33. Gregory Waters, “The Growing Role of Reconciled Rebels in Syria,” International-Review, April 21, 2018, https://international-review.org/the-growing-role-of-reconciled-rebels-….

34. Anonymous, Interview with Author, Online, May 2, 2019.

35. Kirill Semenov, “Who Controls Syria? The Al-Assad family, the Inner Circle, and the Tycoons,” Russian International Affairs Council, February 12, 2018, https://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/analytics/who-contr….

36. Anonymous, Interview with Author, Online, May 13, 2019; Aymenn J al-Tamimi, “The Coastal Shield Brigade: A New Pro-Assad Militia,” Syria Comment, July 23, 2015, http://www.aymennjawad.org/17614/the-coastal-shield-brigade-a-new-pro-a….

37. Gregory Waters, “Syria’s Republican Guard Growth And Fragmentation,” Middle East Institute, December 2018, https://www.mei.edu/sites/default/files/2018-12/RG%20Report%2012-12.pdf.

38. Semenov, “Who Controls Syria?”

39. Tobias Schneider, “The Decay Of The Syrian Regime Is Much Worse Than You Think,” War on the Rocks, August 31, 2016, https://warontherocks.com/2016/08/the-decay-of-the-syrian-regime-is-muc….

40. Anonymous, Interview with Author, Online, May 6, 2019.

41. Anonymous, Interviewed by author, Online, January 24, 2019.

42. Ibid.

43. Anonymous, Interviewed by author, Online, May 3, 2019.

44. Ibid.