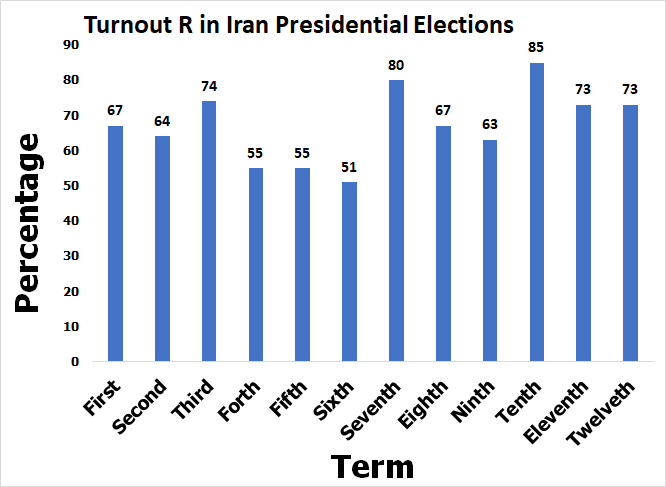

Iran’s presidential election on June 18 is expected to have the lowest turnout of any election to date and the implications are likely to extend far beyond the ballot box. The official voter turnout in post-revolutionary Iranian presidential elections is typically around 50-85%, which is relatively higher than for parliamentary elections. Of course, the official statistics are quite different from the real ones, especially for the elections between 1981 and 1993, but the official data cannot hide the general trends in the electorate’s behavior. The last parliamentary election in 2020 showed a drastic decline in total turnout in 30 out of 31 provinces. According to official numbers from the Ministry of the Interior, turnout was just 42.57%, the lowest of any election in the Islamic Republic’s history. Driving that historic decline was a growing sense among different segments of society that elections do nothing to improve their lives or address the country’s major problems, like strengthening the economy, ending political deadlock and cultural isolation, and empowering civil society to combat corruption and inequality. The bloody suppression of the November 2019 protests and the lack of accountability for the shootdown of Ukraine International Airlines flight 752 deeply affected many Iranians and their willingness to turn out to vote.

Crisis, anger, and apathy

With Iran now facing a number of severe crises — over issues of legitimacy, trust, conduct, efficiency, and emergency management — all of which have been exacerbated by the pandemic, polling data and observations suggest growing public rejection of the two main wings of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI), the reformists and the principlists. Anger, ignorance, and apathy against a background of the systematic violation of the principles of fair and free elections have caused more than half of the eligible voters (60 million) to refuse to engage in the electoral process. Cutting across class, ethnicity, political party, and religious belief, there is a growing realization that change cannot be achieved through the ballot box.

Furthermore, the decision of the 12-member Guardian Council to disqualify many potential candidates from participating in the June election gave those seeking change yet another reason not to vote. Even former and current high-ranking officials like Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (the former president), Ali Larijani (the former head of parliament), Eshaq Jahangiri (the current vice president), as well as dozens of former minsters, Revolutionary Guard generals, and MPs, were disqualified by the council, which ruled out a total of 585 candidates and approved just seven. As a result, it seems as though the circle of power, upon receiving the green light from Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, paved the way for the victory of Ebrahim Raisi, the chief of Iran’s judiciary, in a non-competitive election. While the reasons for this decision remain unclear, it appears to be part of an effort to consolidate power among hard-liners and remove any “moderates” who might risk complicating the transition from the octogenarian supreme leader. Ayatollah Khamenei hopes to see, in what may be his final years, a regime loyalist with limited power as the successor to the two-term President Hassan Rouhani.

The boycott campaign

Now, for the first time in the IRI’s history, a major and unprecedented effort to boycott the election is rising through all ranks of society, bringing together different political groups, activists, and civil society forces and polarizing the election atmosphere. Although the majority of the opposition and reformists seem to support the boycott, some want to vote for Abdolnasser Hemmati and Mohsen Mehralizadeh, conservative reformists and former officials with the Rouhani administration. Even assuming they win, which is highly unlikely, Hemmati and Mehralizadeh would be unable to bring about meaningful change. They are also facing growing criticism that running in a rigged election only ends up strengthening the current authoritarian regime, rather than those protesting it.

The gap between the government and the people is broadening to such an extent that they now live in two totally different and unconnected worlds when it comes to values, policies, and objectives. These two worlds will eventually collide and the upcoming election and its implications are only hastening that process. The government is moving forward with efforts to block changes in internal and external policies, but it has little ability to intensify its suppression and crackdown beyond the current level, especially as the IRI power structure becomes weaker and overwhelmed by issues of functionality. For their part, the Iranian people, tired of their country’s dismal economic outlook, increasing international isolation, and systematic civil rights violations, will refuse to engage in the official political process and begin to look for alternatives. The reformist approach no longer seems to have a chance in Iranian politics, as growing gridlock makes it clear that gradual political change in Iran is impossible.

What’s next?

The bloody repression of protests, the denial of the crime and the attempt to cover it up, remarkable increases in poverty and inequality, corruption, elected bodies’ lack of power, the poor performance of the reformists and the “moderates,” and the demand for justice have all played a significant role in pushing the Iranian people away from the ballot box and to instead seek radical change outside of the IRI power structure. Of course, not all election boycotters have the same motives, goals, and approaches, but the outcome of the widespread boycott of the elections will strengthen the strategy of pursuing structural change in Iran's political arena. A political revolution, whether it be silent or velvet, appears to be a viable approach to addressing the deepening rift between the incorrigible government and the people seeking fundamental and lasting change in Iranian politics.

Low turnout in the 2021 presidential election will open a new chapter in Iranian politics that ends 24 years of efforts to pursue the reformist approach. Efforts to organize social movements, street protests, and further boycotts in other spheres are only likely to grow going forward. The situation is ripe for a large and broad opposition gathering to support a democratic transition outside of the IRI power structure and to end the stalemate inside the ongoing political process. Most important of all, the boycott campaign has create a wave that has swept past the comparatively narrow issue of who is running the country and has instead focused on the future of the country itself and its system of governance.

Ali Afshari is an Iranian political analyst and pro-democracy activist. He is a former student leader and member of the Central Committee of the Office for Consolidation of Unity, the main and largest student organization in Iranian universities during the reformist era. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.