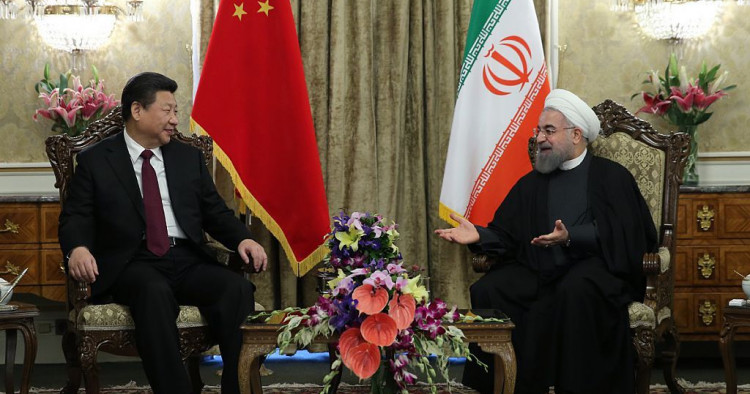

The 25-year agreement between Iran and China that made headlines this past month is far from new. It was first announced in 2016 during a state visit by President Xi Jinping to Tehran, at a time when sanctions on Iran were being lifted as part of the 2015 nuclear deal. Chinese and Iranian officials have been working out the details of the deal ever since as part of a slow process of consultation and negotiations.

This process was doubtless complicated by the sudden uncertainty created by Washington’s abandonment of the 2015 nuclear deal and decision to re-impose sanctions on Iran from 2018 onwards. However, negotiations between Iran and China accelerated again as U.S.-China tensions increased and Beijing began looking for ways to push back on what it calls American “bullying,” such as the extraterritorial sanctions imposed on Iran.

The timing of the latest announcement about the 25-year strategic agreement is, therefore, less about developments in relations between Beijing and Tehran and more about the fast-deteriorating relations between Beijing and Washington. China is looking to identify areas where it can cultivate leverage, and Iran is a prime opportunity.

Iran’s interest in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a global infrastructure development plan, in particular is driven by a few primary calculations:

- It provides potentially considerable economic opportunities for Iran;

- It provides Iran with political insurance against international isolation in the future;

- It has the potential to give Iran an advantage over some of its most prickly rivals, such as Saudi Arabia (which today is a far big oil supplier to China than Iran); and

- While China-Iran relations in the energy sector remain relatively strong, military-to-military ties have great potential for growth.

Trends and drivers

Beijing’s plan to implement the BRI, launched in 2013, was warmly welcomed by Tehran from the outset. The project, which would link China with world markets through an extensive and ambitious set of land and maritime trade routes across Eurasia and adjacent seas, puts Iran in the center of China’s global plans.

While several dozen states are set to take part in the BRI (somewhere between 50 and 65 by some accounts), Iran is one of the key components of the project, which is estimated to cost about $1 trillion in total over a 10-15 year time period.[1]

The basic geography of Iran makes it the only viable bridge from world seas to the landlocked Central Asian states (a market of about 65 million people) and the three states of the South Caucasus (Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, although the latter has access to the Black Sea).

China’s commitment to becoming the predominant economic and political power in the heart of Eurasia cannot be underestimated. To secure its grip over Central Asia, an Iran that is closely integrated into the BRI provides an important form of insurance for the Chinese against alternative options for the Central Asians that might emerge in the future.

At the moment, the Central Asians have three outlets to world markets: east via China, south via Iran, and west via Russia. The successful implementation of the BRI would give China de facto control over two of the three outlets.

Kazakhstan is leading the pack among the five Central Asian states in linking up with Iran, with an eye to connecting to world markets via Iranian ports. In December 2014, a 925-km rail line running from Kazakhstan to Turkmenistan and on to Iran was inaugurated.

In Kazakhstan’s push for a multi-vector foreign policy, Iran has always stood out as an important priority. This was a big factor in its role as a nuclear mediator between Iran and the West during two rounds of talks held in Almaty in early 2013. Meanwhile, in February 2016, the first rail cargo from China arrived in Iran via the Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Iran rail link.

However, the BRI also does create uncertainties for the Iranians. One of Iran’s biggest infrastructure projects in the last decade has been the development of the Chabahar deep-water port on Iran’s Indian Ocean shores.

This project has been much delayed but remains critical for Iran as a way of providing a more commercially viable outlet to the Central Asian states, and thereby turning Iran into an important transit linchpin. To say that the Iranians want to turn the port into a rival of Dubai is not an understatement, even if such a scenario is unlikely in the near term. China has in the meantime invested heavily in a nearby and potentially rival project in Pakistan, the port of Gwadar.

To complicate things further, it is China’s rival, India, which is among foreign states most invested as a partner of Iran in Chabahar’s development.[2] Japan too has been mentioned by Iranian sources as a potential investor in the port project.

Japan is said to be interested in the port’s development for the same reasons as China: to strengthen ties to the 82-million-strong Iranian market while also turning Iranian territory into a conduit to the markets of Central Asia.[3] Nonetheless, for now this potential conflict of interest does not pose an insurmountable obstacle to realizing the Iran segment of Beijing’s BRI plans.

Furthermore, Beijing looks at Iran and Central Asia not only through an economic lens, but also through a security one too. Adjacent to its relatively underdeveloped and often security-deficient western regions, Beijing considers Central Asia its exposed underbelly that needs to be closely integrated into China’s economic and political sphere of domination.

And the Central Asians have been more or less willing partners. China has already replaced Russia as the region’s main trading partner and cooperation is now expected to consolidate around security-centric questions. There is institutional infrastructure in place to facilitate such moves, most notably the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).

Both the Chinese and the Central Asian leaderships consider Iran as an inevitable but perhaps also a desirable security partner. This is not only due to its geography; there is also a shared Central Asian and Chinese reading of Iran as a non-threat when it comes to one key issue: the importing of radical Islam into a part of the Islamic world that has hitherto been largely secular.

Despite Tehran’s vehement commitment to its Islamist ideology, the Central Asians and the Chinese view Iran as formidable nation-state that has in practice and for various reasons largely ceased trying to export its political message to its northern neighbors.

This is welcomed but there is also a structural obstacle that at least in perception terms reduced the Iranian ability to penetrate the region: As a Shi’a Muslim state its Islamist message was always going to have a limited reception in the Sunni-majority Central Asian states or in China.

In contrast, there is a deep fear in both Central Asia and China about the role of Sunni-majority states as a launch-pad for the propagation of radical religious doctrine aimed at their Muslim populations. This fear is particularly relevant to two states from the perspective of the Central Asians: Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. Interestingly, the Central Asian states have kept both at an arm’s length, which has not been the case with Iran.

Witness, for example, that despite huge volume of trade, China has had very little cooperation in the security realm with the Arab states of the Gulf. It was only very recently that Saudi Arabia and China held talks about counter-terrorism for the first time.[4] In contrast, Iran has had a series of security and defense talks with the Chinese and deep Iranian military ties to China go back to the early 1980s.

A poor history of regional integration

The second contributing factor has to do with the Chinese reading of the durability of the Iranian state. Despite its contentious relations with the West, Iran is viewed by the Chinese as an enduring and powerful nation-state in a Middle East that is today home to many failed or failing states (from Yemen to Iraq and Syria to Lebanon and Afghanistan).

The Chinese also see Iran as a country that is nonetheless largely outside any regional economic and security alliances. This is an issue that Beijing is seemingly promising it can help to address via projects such as the BRI. The recent announcement of a 25-year, $400 billion strategic agreement between Tehran and Beijing has to be seen in this same context.

That said, there are again some Iranian suspicions in this regard as well. Take China’s posture toward the long-time Iranian bid to join the SCO as a full member. Russia is widely believed in Tehran to favor Iranian accession to the multilateral collective body, which is led by Moscow and Beijing.[5]

However, the Iranians are not so sure about Beijing’s openness to the idea. In recent years, the organization has repeatedly declined to begin accession talks with Tehran, much to Iran’s disappointment.[6] Iran is kept out while both India and Pakistan — two states that are belligerents — were admitted to the SCO in June 2017.

The posture of the SCO has irked the Iranians to the extent that they are said to be reevaluating their membership bid. In fact, right after Iran’s bid failed an array of Iranian semi-official sources questioned the utility of SCO membership for Iran at this point.[7]

And yet, the desirable political and symbolic value for Tehran of being able to join such groupings as the SCO cannot be underestimated. Since the Islamic Republic came about in 1979, Iran has repeatedly failed to join any collective bodies that can facilitate its diplomatic and economic requirements in any meaningful way. From the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) to the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), Iran’s experience with multilateral efforts has more often than not been disappointing. And Tehran’s recent experience with economic isolation due to its nuclear program has only increased its appetite for integration into collective bodies that might be able to shield it from punitive Western measures in the future.

Pull factors in Tehran

While Chinese investment in rail, road, ports, and other infrastructure projects and general trade are all reasons for Iran to welcome the BRI, there is also a domestic Iranian factor that facilitates Beijing’s plans. That is linked to the hardline faction in Iran that has for a long time argued that Tehran should prioritize diplomatic and economic ties with states like Russia and China over those in the West. This posture is above all shaped by ideological preferences.

This policy began as a motto back in the 1990s, but was a reality by the end of the Mahmoud Ahmadinejad presidency. By 2013, when Ahmadinejad left office, China alone represented about one-third of Iran’s total trade.

And some of the same hardliners, particularly those found in the ranks of the political-military Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), continue to argue for closer ties to China. But while the hardliners in Tehran see China an important political counterweight to the West, the moderate faction in President Hassan Rouhani’s government views it as an essential player that can complement Iran’s overall attempts to break its past international isolation.

In fact, Iran-China military-to-military ties have expanded noticeably since Rouhani entered office in 2013, especially after the 2015 nuclear deal. Defense Minister Hossein Dehghan first visited Beijing in May 2014 and signed an agreement on military cooperation. Tehran and Beijing also signed a deal to jointly combat terrorism. Much of the vision for such cooperation was laid out in President Xi’s January 2016 state visit to Tehran. The two states then agreed to expand trade to $600 billion over a 10-year period while also framing stronger cooperation as part of a 25-year plan.[8]

As with Tehran’s ongoing discussions with the Russians, Iran is said to be weighing the idea of giving the Chinese military access to its air and naval facilities. It also has to be remembered that Iran and China are today almost in agreement on some key questions in the Middle East, including support for the regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria.

China and Iran will inevitably continue to develop closer ties, mainly in the economic field. While Iran and China have similar views on the international order (anti-U.S. hegemony, emphasis on sovereignty), China will likely be reluctant to get too entangled with Iran given the risky business environment (and threat of sanctions) and Iran’s proclivity to engage in troubling interventionist policies in the Middle East.

Finally, there is also still a broad agreement among observers that the U.S. serves as a significant constraint on deepening Iran-China relations, given China’s desire for profitable trade with the U.S. and ongoing Chinese adherence to U.S. sanctions on Iran.

Nonetheless, at a minimum, even the publicity around this agreement is seen by Tehran as undermining Washington’s argument that Iran is isolated because of the “maximum pressure” campaign. At best, the 25-year strategic deal between Tehran and Beijing can be Iran’s “insurance policy” if U.S. sanctions continue and the U.S.-China fight escalates. In short, this deal is not just a piece of propaganda by Tehran.

Alex Vatanka is the director of MEI's Iran Program and a senior fellow with the Frontier Europe Initiative. The views expressed here are his own.

Photo by Pool/Iranian Presidency/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

[1] http://blogs.worldbank.org/eastasiapacific/china-one-belt-one-road-initiative-what-we-know-thus-far

[2] http://nationalinterest.org/feature/why-iran-india-are-getting-closer-18336

[4] http://saudigazette.com.sa/saudi-arabia/saudi-arabia-china-sign-security-cooperation-pact/

[5] http://www.presstv.com/Detail/2016/04/07/459588/Iran-Russia-SCO-Zarif-Lavrov-Baku-Karabakh/

[6] http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2016/07/iran-shanghai-cooperation-organization-sco-accession.html

[7] http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2016/07/iran-shanghai-cooperation-organization-sco-accession.html

[8] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-23/china-iran-agree-to-expand-trade-to-600-billion-in-a-decade

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.