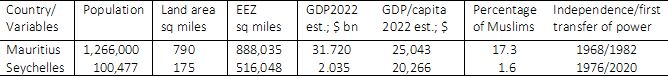

Mauritius and Seychelles are two small island states in the southwestern Indian Ocean. They are both former British colonies and have been members of the British Commonwealth since independence. Both are among the most prosperous African countries, blessed with stable democratic governments, high levels of public safety, a year-round warm climate and uncommon natural beauty. They boast the highest rankings in the United Nation’s Human Development Index among Sub-Saharan African countries by far (Mauritius 63rd, Seychelles 72nd — out of the 191 total countries ranked — the next highest, South Africa, is 109th).[1]

Sources: International Monetary Fund, 2022.

The seemingly precarious geographic status of small island states also comes with a major advantage: they enjoy Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) many times larger than their land mass. In fact, the EEZs of these two states are so large that, even though they are more than a thousand miles away from one another, there is an almost 153,000-square mile overlap between them which they manage jointly and without dispute. Needless to say, while such large EEZs are virtually impossible for small island states to effectively control, they also hold the promise of unexplored riches in and under the sea.

Small island states by definition are vulnerable and must pursue activist foreign policies, participate in a range of regional and global international organizations, and seek allies wherever they can. Traditionally, given that the largest ethnic group is descended from indentured servants from India, Mauritius has had particularly close ties with New Delhi. But Mauritian political elites have been quite successful in harnessing the emerging rivalry between India and China in the southern Indian Ocean region, obtaining investments in a wide range on industrial, commercial, and infrastructural projects. During the Cold War, Seychelles — like Mauritius, officially a member of the non-aligned movement — was in effect firmly in the socialist camp, though it hosted a US tracking and spying station in the mountains above the capital, Victoria, while the Soviet navy’s ships were frequently moored in its harbor.[2] Both countries have cultivated relationships with Gulf monarchies and have handsomely benefited from them.

Mutually Supportive Political Ties

Soon after independence Mauritius and Seychelles established diplomatic relations with most Gulf monarchies. These links have continued unabated since then and have grown closer. Obviously, this is a largely unbalanced relationship as for the members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) the nexus with two small island states is not a priority. For Mauritius and Seychelles, however, links to the wealthy Arab monarchies — particularly to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia — are far more important and have been carefully cultivated.

Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Kuwait have decades-long traditions of providing support in a variety of ways to the two island nations. Numerous bilateral agreements have been concluded between them from establishing university scholarships to cooperating in security operations. Collaboration in anti-piracy activities, especially critical during the first two decades of this century — when it was the most significant external security threat facing these countries — has been an important dimension of maritime diplomacy between the Mauritius and Seychelles and the GCC states.[3] The Emirates extended a $15 million grant to rebuild the Seychelles Coast Guard and donated five boats to help patrol its shorelines.[4] Oman, given its own long Indian Ocean coast, had also held talks with Mauritius and Seychelles on piracy issues. Kuwait has provided assistance to the Seychelles through the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development since 1985, helping to develop a number of off-shore fishing and infrastructure projects as well as financing a primary school in Victoria.[5]

In April 2022 the Seychelles signed an agreement with the Emirates to modernize and transform its public service. The three-year project will help develop and improve government activities and practices, interaction with the public, and generally enhance the effectiveness of Seychelles’ public administration.[6] Seychelles’ finance minister Naadir Hassan said that embracing the results-based management framework and digitalization of public service would be spur a major improvement in increasing the delivery of high-quality public services. The UAE has also strengthened several of Seychelle’s community project initiatives. For instance, it has financially supported the construction of public housing units. Moreover, the Emiratis have contributed to the wind turbine farm emerging on Ile du Port, just outside of the capital, Victoria. These ventures have been made possible by grants provided by the Abu Dhabi government and administered by the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development.[7] The Emirates also donated 40 buses for the Seychelles public transport authority.

Behind much of this aid to Seychelles was Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan (1948-2022), the second president of the UAE and the ruler of Abu Dhabi (2004-2022). His interest in the Seychelles was not entirely altruistic. Starting in 1994 he bought up nearly 100 acres of the island where he built a palace in 2005. The construction of the mountain-top castle was highly controversial owing to the massive environmental damage it caused though Khalifa made reparations and compensated the affected 360 households.[8]

Unlike Seychelles, Mauritius has been a multiparty-democracy from independence. It, too, has significantly benefited from its links to GCC states and, in turn, has supported them according to its limited capabilities. When, in 2017, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt isolated Qatar for its allegedly different approaches to foreign relations and international terrorism, Mauritius was one of the nine Arab countries that severed relations with Doha in June 2017.[9] After all, political elites in Port Louis had to be pragmatic and realize that they had more to lose if they withheld support from their primary beneficiaries of the region (Saudi Arabia and the UAE) than sticking with Qatar. Still, in a remarkable example of political brinkmanship just a few months later, in October 2017, the Prime Minister and the Foreign Minister of Mauritius met with Qatar’s non-resident ambassador in Port Louis, “discussing bilateral relations” and “ways to boost and develop them.”[10] Presumably the commercial benefits of connections with Qatar outweighed the advantages of being one of the states that supported isolating Doha. Small island states, after all, must be exceedingly pragmatic.

Mauritian political elites and underprivileged societal groups have also been the beneficiaries of Riyadh’s largesse. Unlike Seychelles 1,100 miles to the north, Mauritius is hit by devastating cyclones with troubling regularity. Port Louis’s GCC allies have just as regularly extended donations, aid, and grants to support rebuilding efforts. For instance, in May 2019 the King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Center announced a donation of $10 million to provide humanitarian assistance. The grant funded projects to build shelter, assist the food and health sectors, and to assist with rapid intervention. The Saudi Fund for Development contributed low-interest loans and grants for the establishment of a teaching hospital, a multi-sports complex, and social housing sector projects. Riyadh also airlifted 50 tons of dates to lighten the suffering during the crisis.[11] Expanding relations between the two countries gained further momentum with the 2018 opening of a Consulate General of Saudi Arabia in Mauritius and a Mauritian Consulate in Jeddah — partly financed by the Saudis — soon after.

Growing Trade and Cultural Relations

Undoubtedly the largest segment of the commercial relationship between Mauritius and the Seychelles and the GCC is tourism. From the busiest airports of the Gulf kingdoms — Doha, Abu Dhabi, and Dubai — the islands are a 4-6-hour flight away and offer a comparatively mild yet warm climate, pristine beaches, well-developed infrastructure, and many exclusive resorts.

The diminution of Chinese visitors to Mauritius and Seychelles served to redouble the efforts of these countries to turn toward the GCC, especially its most populous nation, Saudi Arabia. The Mauritius Tourism Promotion Authority (MTPA) has devised campaigns to position the Mauritian islands as “a destination choice” for Saudi travel agents. Unsurprisingly, the COVID pandemic which brought international travel to a near standstill, was a particularly challenging time for the two island countries. Mauritius put in place a robust vaccination strategy and safety protocol that proved to be quite effective in protecting its population but shut down its tourism sector. To cushion the blow and help make-up for the lost revenue, the UAE provided financial assistance to both countries.[12]

Since early 2022 tourism from the Gulf has increased partly in response to the islands’ marketing campaigns. In May, Saudi Arabia and the Seychelles signed a Memorandum of Understanding to boost tourism, create job opportunities, and promote sustainable development. Direct flights to the Seychelles by Flynas, a Saudi airline, began in July. Air Seychelles and Air Mauritius became beneficiaries of the rapprochement between some of the Gulf monarchies and Israel as they received overflight rights from Saudi Arabia’s government for their flights to and from Tel Aviv. This has been a boon to both airlines as Israel has been a leading market for them and overflight rights allows them to save fuel and add passengers to their flights.[13] The MTPA’s new marketing campaign, “Explore the Unexplored Mauritius,” was aimed specifically at GCC countries.[14] Mauritius recorded 470,640 arrivals in the first half of 2022, far above 2021 numbers but still 40 percent below 2019 figures.[15]

Tourism is not the only source of the commerce between the island states and the Gulf. As a growing number of Gulf nationals — especially Emiratis — have purchased holiday homes in Seychelles and Mauritius, GCC corporations also increased their investments not just in hotels but also in the banking and construction sectors. Mauritius also is home to a growing knowledge economy, with several small but ambitious technology companies and consulting firms entering the GCC market. For instance, Abler, a Mauritius-based independent compliance consulting firm — its expertise lies mainly in anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing to navigate international regulatory challenges — recently launched operations in the UAE.[16] Saudi Arabia is keen to expand its own tourism sector, and Saudi companies have recently hired Mauritian travel consultants with widely recognized expertise. The Tourism College of Oman and the Seychelles Tourism Academy are also planning exchanges. More generally, Oman — which has established bilateral relations with Seychelles in 1983 — has in recent years become interested in investment opportunities in the Seychelles as well as establishing direct flights to the island from Muscat for its national carrier, Oman Air.[17]

Finally, the Muslim community in Mauritius — Islam is the third largest religion after Hinduism and Christianity — has cultivated close ties with their brethren in the GCC, particularly in Saudi Arabia. Islamic revivalism has played a significant role in the formation and articulation of ethnic and religious identity and, in turn, lent focus to the political opposition activities among the minority Muslims.[18] In 2000 Riyadh financed the construction of an Islamic Cultural Center in Port Louis that has become the focal point of Muslim life on the island.[19] The Kingdom has also provided assistance to Mauritian pilgrims for Haj. Saudi Arabia’s uninterrupted political and commercial engagement in Mauritius has been a boon for its coreligionists on the island.

Conclusion

The relationship between Mauritius and Seychelles and the Gulf kingdoms have lasted since independence and have been free of disputes and controversies. The island states have provided political support for the Arab kingdoms in international organizations and forums as well as commercial opportunities for the GCC member countries. The two small island states have been fortunate for the aid, investments, and multifaceted patronage they have received from the Gulf. These mutually advantageous ties are likely to further develop and proliferate in the foreseeable future. GCC states must diversify their economies and need stable and friendly countries receptive to their investments. (Mauritius happens to be by far the top African state both in terms of persistence of democracy as well as in terms of ease of doing business.[20]) It appears that only unforeseeable calamities like the recent pandemic or a similarly improbable politico-economic crisis or collapse in either side of the equation might cloud these horizons.

[1] UN Human Development Reports, September 8, 2022, https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/country-insights#/ranks.

[2] See Sir James R. Mancham, Seychelles: The Saga of a Small Nation Navigating the Cross-Currents of a Big World (St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2014), 111-112.

[3] See Lisa Otto, “Exploring Maritime Diplomacy of Small Island Developing States in Africa: Cases of Mauritius and Seychelles,” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region (2022): 1-16.

[4] “UAE and Seychelles – ‘True Friendship and True Partnership,’” Nation (Seychelles), January 8, 2011.

[5] Daniel Laurence, “Kuwait Hopes to Advance Investment Relationships with Seychelles, New Ambassador Says,” National, July 9, 2019.

[6] Betymie Bonnelame, “UAE to Help Seychelles Modernize and Transform Its Public Service,” Nation, April 6, 2022.

[7] “Seychelles and UAE Set to Strengthen Cooperation through Ongoing Community Projects,” Guardian, July 2, 2022.

[8] “Seychelles Up in Arms over Emirati Palace,” Independent, April3, 2010; and Margaret Coker, “Sheikh Abode a Sore Point in Seychelles,” Wall Street Journal, September 9, 2010.

[9] See Zoltan Barany, Armies of Arabia: Military Politics and Effectiveness in the Gulf (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 203-206. More specifically, see Euan McKirdy, “Middle East Split: The Allies Isolating Qatar,” CNN, June 7, 2017.

[10] “Mauritius Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Meet Qatar’s Ambassador,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mauritius, October 19, 2017.

[11] “Saudi Arabia Donates USD 10 Million to Support Mauritius,” Reliefweb.int (Riyadh), May 12, 2019.

[12] “Sheikh Mohammed and President of Seychelles Discuss Enhancing Bilateral Relations,” Khaleej Times, August 12, 2022.

[13] Devash Mehta, “Air Seychelles Receives Saudi Arabia Overflight Permission,” Simple Flying, August 3, 2022.

[14] “Mauritius Reaffirms Strategic Importance of GCC Countries,” Zawya, June 21, 2022.

[15] Theodore Koumelis, “Mauritius Tourism Promotion Authority Leads a Successful Mission to Saudi Arabia,” Travel Daily News, September 16, 2022.

[16] Shilpa Annie Joseph, “Mauritius-based Abler Expands Its Operations into the UAE,” GCC Business News, September 11, 2022.

[17] Sharon Ernesta, “Tourism, Blue Economy, Fisheries Top Agenda of Oman’s Ambassador to Seychelles,” National, May 18, 2021.

[18] See Odvar Hollup, “Islamic Revivalism and Political Opposition among Minority Muslims in Mauritius,” Ethnology, 35:4 (Autumn 1996): 285-300.

[19] “Muslim Community Voices Support for Saudi Arabia,” Saudi Gazette, March 1, 2016.

[20] According to World Bank data, in 2021 Mauritius was ranked 13th in the world from the perspective of ease of doing business. See https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IC.BUS.EASE.XQ

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.