This paper is part of MEI’s Strategic Foresight Initiative, which examines key drivers and dynamics at work in the region, thinks strategically, creatively and rigorously about various scenarios, risks and opportunities, and uses methodologically sound approaches to help decision-makers chart a course forward.

Executive Summary

Conflict and instability have been constant features of the Middle East for decades. Over the most recent decade, four civil wars and fraught relationships between the major regional powers have been pushing the region toward a potentially perilous political and economic future. We know that the COVID-19 crisis is disrupting the status quo on nearly everything, including regional conflict. What we do not know is how that disruption today might worsen — or improve — the trendlines of those conflicts as we head toward 2025.

In this MEI Strategic Foresight Initiative paper we employ a scenario-based methodology to explore this question. We look at how the confluence of three dimensions of the response to COVID-19 could shape the conflict dynamics of the Middle East. Some of our scenarios portend the pernicious effects of the virus moving the region even further away from integration and closer toward acute insecurity. But there are also some counter-intuitive outcomes, in which one sees transition to at least some greater degree of stability, or even the prospect of a “wake-up” moment where leaders move toward what we call a “resilience regional architecture.”

Informed by the scenarios, our view “from 2025” suggests three policy considerations will be particularly important. One is acknowledging the interrelationships between the public health, economic, and social response to the pandemic, and that their confluence will affect conflict dynamics. The imperative is crafting truly multi-dimensional response policies and action plans, and recognizing the second- and third-order effects they will have on conflict in the region. A second is to build on the baby steps taken thus far in the health response to the COVID-19 virus, for a broader strengthening of regional institutions. Notions of a regional cooperation “architecture” historically have centered only on security and other geopolitical concerns. Now that health concerns are front and center for all in the region, they could be the missing link enabling such a framework to be considered in a new way. Finally, steps to dial down — or at least stop dialing up — the enmity among the major regional powers are pivotal. That burden is first and foremost on Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Israel themselves. But there also needs to be a greater willingness in Washington’s and other powers’ foreign policies, at least for now, to “do no harm.”

1. Introduction

If you are skeptical after reading a title making assertions about the future of the Middle East, you likely have company. Why, in an environment of immense near-term uncertainty, should we spill ink projecting out five years?

It is exactly that uncertainty that makes considering the future critical. A wide range of actions in the next 3-12 months could be taken by actors in the region and international community in response to COVID-19. It remains to be seen which ones actually will be taken, and how.

So it is critical that we examine potential different combinations of responses and what their consequences — intended and unintended — might be. Those consequences will be not only near term, but also will shape the region longer term. Another way of saying this, to paraphrase the novelist William Gibson: the future is already here, in the COVID-19 response interventions that are being distributed.

Our peering into the future is focused not only on the pandemic itself, but also on what it could portend for how conflictual the Middle East may be in 2025, and what those conflicts may look like in its wake. Will countries and their populations see common cause in the health care crisis that knew no boundaries? Will the turmoil and uncertainty further deepen ethnic, national, and sectarian divides? What of the many possibilities in between those two states?

We explored how responses to COVID-19 could play out, with an eye toward how they may be important drivers of change for conflict dynamics in the region. Different combinations of how the drivers could manifest suggest different scenarios, several of which we developed (Section 3 below), set in the year 2025. In that section we also explore what Middle East conflict would be like in each scenario. As you will see there, and in Section 4, the interplay of the COVID response dimensions does not affect the conflict patterns in the region in obvious ways in every case. In our conclusion (Section 5), we reflect on some important policy considerations for shaping how responses to the pandemic and its impacts could affect conflict in the region.

A question of course is, how sensitive are the conflict dynamics in these of any scenarios to policy intervention, and at what level? The region does not have a great history of success in that regard. But the COVID-19 pandemic is upending innumerable assumptions that how things have been in the past is how they will or “must” be in the future. And so considering the possibilities, and the policy interventions they point toward, is important.

"To paraphrase the novelist William Gibson: the future is already here, in the COVID-19 response interventions that are being distributed."

2. The Drivers in Brief

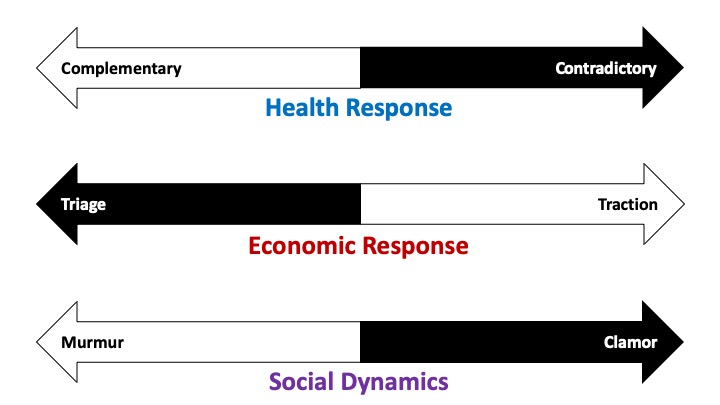

We considered opposite ends of the spectrum for three COVID-19 related drivers of change:1

-

Health response: Will the efforts by actors at the individual nation, regional, and international levels complement or contradict one another?

-

Economic response: Will the responses of governments to the economic crisis, and their interplay with the economic fundamentals and policies of individual national economies, be short-term triage, or more focused on longer-term economic traction and recovery?

-

Social dynamics: Will the social response to COVID-19 meld with people’s emotions about issues such as political inclusion, sectarian strife, social safety nets, and governmental legitimacy in the form of a murmur, or a clamor for change?

Health Response: “Complementary” sees actions at the national, regional, and global level on managing the health crisis relatively aligned and mutually supportive, in effect if not necessarily by design. At the “Contradictory” end of the spectrum, actions or inaction by external powers, regional leaders or bodies, and individual national governments take inadequate account of each other. In some cases they even are in conflict, reflecting differing priorities.

Economic Response: “Traction” sees the soundness of their economic fundamentals helping governments in the region execute a response reasonably effective both in limiting the damage in the short run and positioning the economy for recovery in the medium to longer term. “Triage” sees short-term economic exigencies combining with already-weak fundamentals to make response actions today interfere with and push back medium- to long-term recovery prospects.

Social Dynamics: “Clamor” sees already-challenged legitimacy formulas erode further as populations’ responses to the COVID-19 crisis aggravate expressions of preexisting sentiments about unrelated social and political issues — and vice versa. “Murmur” sees that, while societies do not become meaningfully more coherent, there is diminution of hostility in inter-sect strife and few protests aimed at governments struggling to cope with the COVID crisis.

"By Ramadan in 2023, people had reached their breaking point and protests broke out that swelled in size daily for weeks. Two years later, the slow burn became a roaring fire."

3. The Scenarios

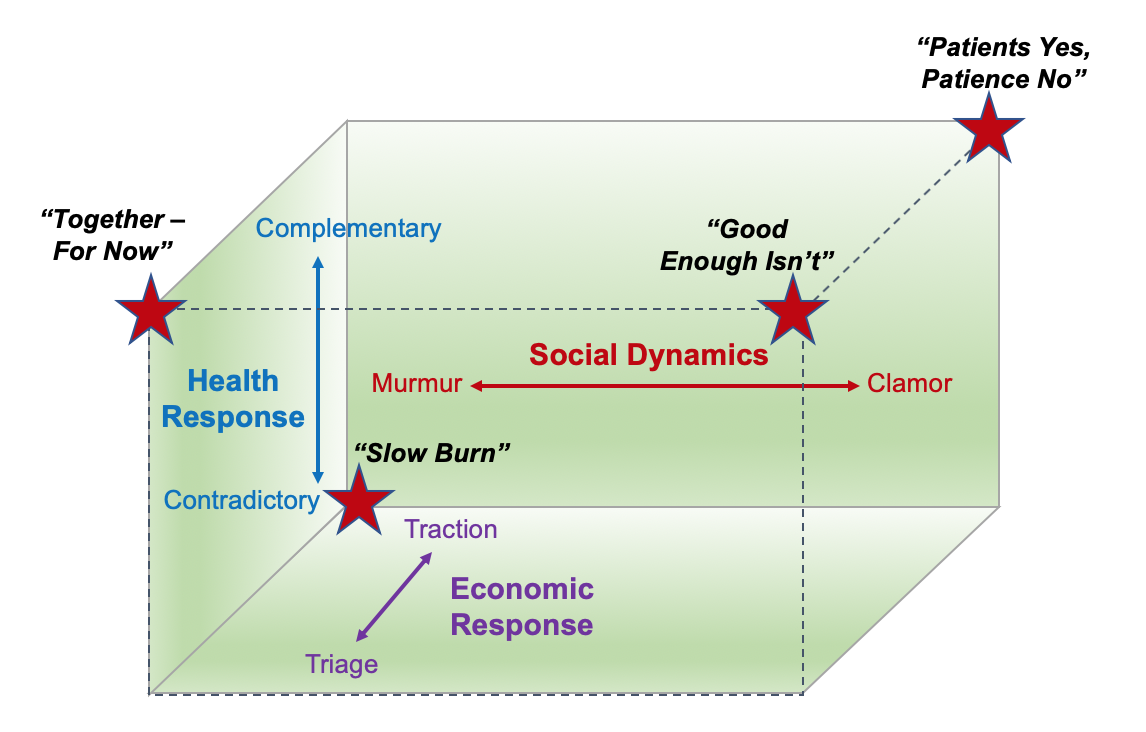

The combinations of two ends of a spectrum for each of three drivers play out in eight distinct ways, as depicted at the corners of the cube in the figure below. We “named” four of those combinations and developed the scenarios they suggest to illuminate some of the particularly important conflict dynamics possibilities.

Here we provide a synopsis of each of the four selected “Year 2025” scenarios. They are intentionally brief, only scratching the surface on how the drivers interact with each other. In each, we also examine the conflict dynamics in that scenario. Our ongoing work is continuing to develop the scenarios and to further explore the driver interactions and the conflict dynamics.

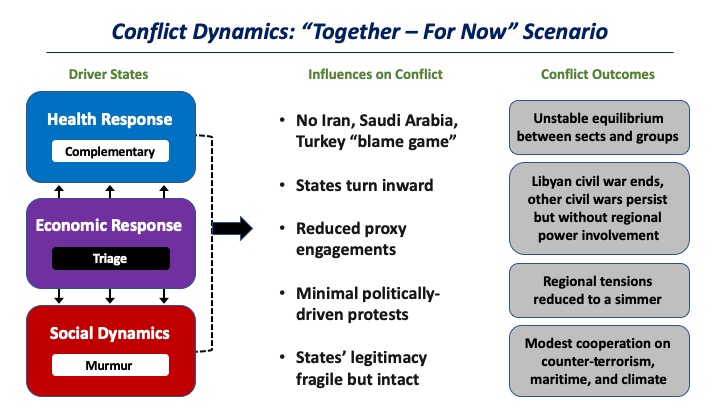

Scenario: “Together — For Now”

Health Response (Complementary), Economic Response (Triage), Social Dynamics (Murmur)

Despite a slow start, the health care response to the virus in the region shifted into higher and better synchronized gear in the summer and fall of 2020. Data-sharing and collaboration among health care workers and scientists across borders was robust. National governments worked to coordinate their border controls, travel bans, and decision-making around stay-at-home orders and economic shutdowns. The strong health response was mirrored by most regional governments in mitigating the pandemic’s short-term impacts on their economies. Even those with relatively constrained means provided substantial liquidity support measures, support to private sector employers, spending and revenue measures, and (in the Gulf Cooperation Council) cash transfers to their huge guest worker populations. But now in 2025, the recovery has virtually no momentum due to the short-term focus of the economic measures in 2020-21. Restiveness in most populations in the region was low throughout the early days of the crisis, and remains so in 2025. Rather than put the public health and economic responses at risk by having unrest lead to some governments’ collapse, many saw the value in biding their time on issues that had been divisive prior to the pandemic. The legitimacy of political systems and the leaders of the systems has actually risen to a degree in the eyes of many.

Conflict dynamics in the pre-pandemic Middle East reflected zero-sum thinking among the regional powers, other national actors, and international actors. While there were common interests served by regional stability, this abstract objective was crowded out by the security dilemmas of endemic conflicts that encouraged escalation, not cooperation. In the “Together — For Now” scenario, COVID-19 changed this. On the whole, while the region likely would not be fully stabilized in terms of conflict mitigation, we could expect at least an unstable equilibrium. Many might fear that unrest would further destabilize already weakened governments and put effective public health and economic relief measures at risk. The resulting relative calm among most populations region-wide would help give governments much-needed breathing room.

Pressing short-term interests in cooperating on the health response, particularly among Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia, could produce modest spillover effects onto other issues requiring cooperation. These could include some winding down of proxy roles in Yemen and stabilizing the tense situation in Iraq. Also, in this scenario we could finally see resolution to the blockade of Qatar by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt. While rivalry certainly would persist between these regional actors on a range of issues, the tenor of the relationships could be expected to evolve into something less venomous. And if the worst infection and death outcomes were avoided, as the relatively collaborative health response would suggest, there would be less of a tendency for governments to play the blame game.

A diminution of conflict between the regional rivals also would be reinforced by a desire to finally begin turning a corner in their anemic economies. In this scenario, recovery is still stalled due to the short-term financial “triage” support to people and businesses in 2020 and 2021. In 2025, and likely even sooner, thegovernments would be more focused on jump-starting their economies than on stoking legacy animosities with their neighbors. Competitive positioning as they try to create economic momentum likely would not spiral out of control or create heightened tensions. The need for economic growth could even catalyze some long moribund trade relations between countries, such as Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

With the regional actors in a more constructive posture in ongoing public health efforts, and focused inward on their economies, we could see a lull in the proxy engagements in some of the civil war zones. By the timeframe of the scenario, while the situation in Yemen still would be nothing approximating peace, it likely would shift away from a Saudi-Houthi conflict to conflicts among the indigenous actors. The Libyan civil war would effectively be ended if turning inward led to the end of support for General Khalifa Hifter by Russia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, and attenuated support for the Tripoli government by Turkey and Qatar. Syria likely also would move to a different phase of its war. Proxy involvement by Iran, Hezbollah, Turkey, and Russia might lessen, but ISIS could take advantage and launch an all-out assault on the central governments in Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, further threatening the stability of already weakened and unstable countries. Overall, in the conditions envisioned in this scenario, civil wars would persist, but in a new phase with the regional powers’ retrenchment.

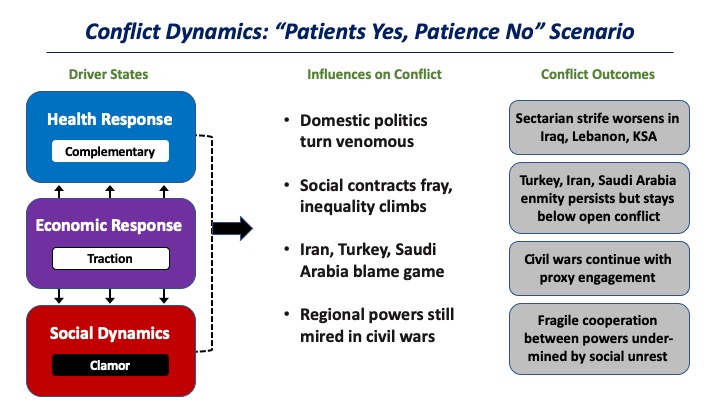

Scenario: “Patients Yes, Patience No”

Health Response (Complementary), Economic Response (Traction), Social Dynamics (Clamor)

Most governments in the region were cautious in their immediate actions to address impacts of the pandemic on their economies. Cash transfers, temporary tax relief, and other measures were capped at modest levels. The focus of the economic response was much more on business than people. The biggest focus was investment in the health care system. Helped by the global economy rebounding pretty well, the approach in the region has shown success, but not without controversy. On the health front, there were fewer infections and deaths than many had feared. This got a monumental boost from the global philanthropic community. Other aspects of the health response also benefited from the surprising degree of collaboration by the countries of the region throughout 2021. At first, people were pleased by how their leaders and the international community rose to the occasion on both the health and economic fronts. But the honeymoon didn’t last long. With governments prioritizing a stronger and more confident eventual economic recovery, the poorest found themselves in dire straits. Grievances unrelated to the pandemic reemerged and began to intensify, fanned by what many characterized as a purposefully uneven distribution of economic aid and the effects of the post-pandemic economic recovery.

In this scenario, we would expect conflicts at the national level to have worsened in the five years since the advent of the COVID crisis. Rather than promoting solidarity or even wary tolerance among regional actors, the scenario envisions the public health response in Iran, Turkey, Israel, and Saudi Arabia falling victim to domestic politics. If it did, sectarian conflicts in Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Lebanon plausibly would flare. Iraq could descend again into Sunni-Shi’i conflict, contrary to its “Iraq-first” nationalist pathway in the pre-COVID-19 real world. Politicizing the health response would worsen rather than help with the legitimacy challenges that most governments in the region were already facing at home before the pandemic. Regardless, the conditions in a scenario like this one likely would push some of them to try to paper over these divides by creating the perception of a common outside enemy.

Governments in “Patients Yes, Patience No” would face other inconvenient truths as well that could affect conflict dynamics. While in 2020 and 2021 they act responsibly and invest in the long-term economic interests of their countries, in this scenario they get little credit for it from their populations. If the initial subsidies to stabilize the economy short term ran out, before long-term economic traction could be created, the unequal effects of recovery could fuel societal divisions. This would be a risk particularly where there is a history of sectarian conflict, violence, and disenfranchisement, such as in Lebanon, Iraq, and even Saudi Arabia. In these countries, in the 2025 of this scenario, violence could be expected to be worse than it was in 2020.

With an interplay of the drivers like “Patients Yes, Patience” envisions, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Israel, and other regional powers could not afford to be in open conflict with one another. To do so would put the revival of tourism to the region, international trade, and other essentials of their economic recovery at risk. At the same time, they would have no incentive (and little pre-COVID “muscle memory”) to devote energy to collaborating to dampen tensions in weaker countries such as Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Libya, Yemen, and Syria. If anything, they likely would still be calculating that blaming their regional rivals for stoking sectarian and other rifts in those countries would distract their own restive populations. Calls from outside the region for leveraging the COVID crisis aftermath to finally spur movement toward cooperative security would be lost in the clamor. With no effective conflict mitigation structures in place, temperatures would continue to rise in national-level conflicts across the Middle East. The muted tensions between the regional powers would be far from guaranteed.

"Despite the enormity of the challenges that the pandemic poses, we could expect some of these conflicts to escalate."

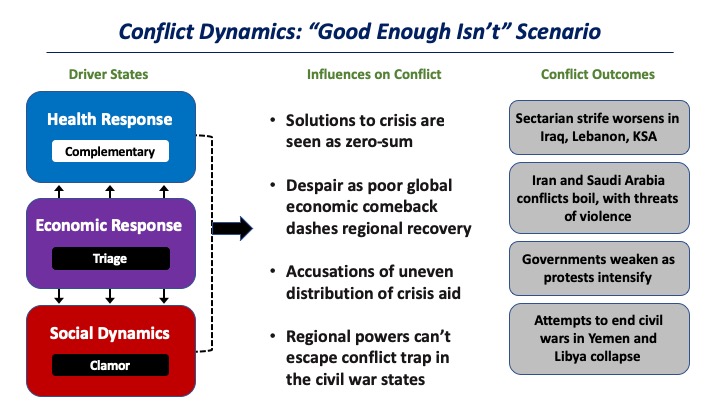

Scenario: “Good Enough Isn’t”

Health Response (Complementary), Economic Response (Triage), Social Dynamics (Clamor)

In summer 2020, people across the region poured into the streets demanding greater resources and coordination for the public health response to COVID-19. The acknowledgment of these voices was a significant and superbly-orchestrated World Health Organization-led intervention that by mid-2021 had largely contained the pandemic, with a spread and toll short of what many had feared. Popular outrage about the initial health response diminished, but it was soon replaced with even greater unrest when measures to soften the economic impacts of the pandemic proved inadequate. Most of the countries could ill afford to provide the measures they did at the scope and scale they did. But they bet, unwisely, on economic recovery in the rest of the world kicking in quickly and strongly enough that they could regain footing in their economic fundamentals. The popular rage had fertile ground to grow in given the long-simmering grievances and discontent in the region. Many claimed — falsely — that access to treatment for the virus and to short-term economic aid were being unevenly distributed on sectarian lines. While trying to orchestrate the largely successful health response and the largely flailing economic responses, governments found themselves with continuous and morphing internal security management problems.

Conflicts between the regional actors would be accentuated by several factors in the “Good Enough Isn’t” scenario. In fact, despite the enormity of the challenges that the pandemic poses, we could expect some of these conflicts to escalate. The effectiveness of the health response in this scenario is due more to complementary efforts of entities from outside the Middle East than those within the region. National governments see and treat this external aid in zero-sum terms, as they historically have viewed each other on most issues. And with their economies in 2025 markedly weaker than was expected, from the drain of their early “triage” measures, efforts to finally kickstart recovery likely would be viewed in the same way. The two countries most worrisome in this regard are Iran and Saudi Arabia. In the logic of this scenario, the potential for shooting wars, while a low probability, could not be discounted.

Alongside these dynamics, we would envision Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel to remain tethered to the conflict trap of the civil wars in Yemen, Libya, and Syria, accentuating the divides between them. Their engagement in these conflicts likely would continue even as they pour resources in 2020 and 2021 into short-term relief of the pandemic’s economic impact, with assumptions of near-term global economic recovery. An active war economy would persist in the civil war zones — especially in Syria. Illicit and criminal networks there likely would enrich themselves on whatever modest economic relief the weak central government might try to provide the population. In Yemen and Libya, with no real governments to distribute aid and no resources for it, the civil wars presumably also would persist. And while outright armed clashes internally might not necessarily be on the horizon for them in this scenario, civil strife would worsen in Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. Some segments of some societies would have done well under the nascent economic recovery by 2025. But that would be in sharp contrast to those that hadn’t. This easily could ignite old sectarian and ethnic tensions.

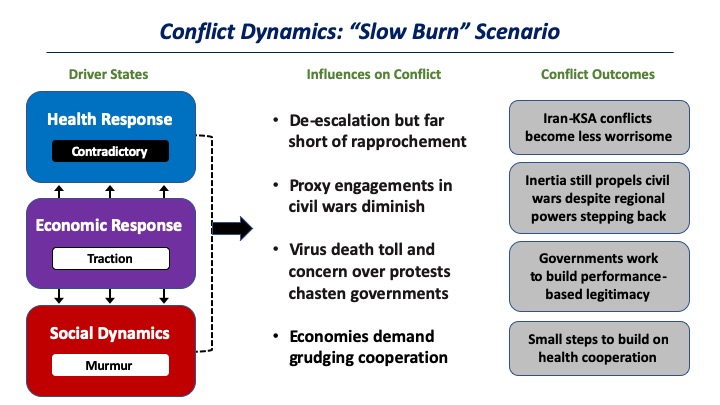

Scenario: “Slow Burn”

Health Response (Contradictory), Economic Response (Traction), Social Dynamics (Murmur)

Streets and public squares throughout the Middle East were deafeningly quiet from the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak all the way until March 2023. People were demoralized by the death toll and the efforts it took to get care. Their struggles to hang on were deepened by what the world agreed was a meager response by governments to the immediate economic impacts of the pandemic on everyday people. The region’s medical and public health response to the virus was characterized by internal inefficiencies, inability or refusal to work or share supplies with their regional neighbors or even international health organizations, widely varying enforcement of travel bans and stay-at-home orders, supply chain problems affecting vaccine distribution, and many other problems. In the economy, early relief to eligible small businesses and individuals was dwarfed by bailouts for the largest industries on which long-term recovery relied. Overall, the strategies set in motion early in the pandemic to position economies for a strong recovery with sustainable results were starting to work. But by Ramadan in 2023, people had reached their breaking point and protests broke out that swelled in size daily for weeks. Two years later, the slow burn became a roaring fire.

In this scenario, three years after the first cases of the virus were detected in early 2020, we envision a bleak recognition by governments and populations alike. The COVID-19 pandemic would have killed more people in the Middle East than all of the wars combined over the past 70 years. The first few years of the crisis see only murmurous aggrievement at the failure of national, regional, and international governments on the health front. But by 2023, we would expect governmental leaders across the region to see the prior calm exploding, putting at risk their investments in regaining long-term economic traction in their countries. Combined with their and the world’s reflection on the grim death toll, it is plausible — perhaps even likely — that they would begin to see the necessity of regional cooperation in a new way.

In the first few years after the virus hits in “Slow Burn,” there would be a degree of deescalation in the sabre rattling that had characterized 2019 and early 2020. But it would be far from rapprochement. Exigencies of the pandemic logically would lead to deintensification of proxy involvements in the civil wars of Syria, Libya, and Yemen. Those wars themselves likely would not deintensify, but more plausibly would grind on with an inertia that even the skyrocketing death toll from the virus in those countries couldn’t arrest. At some point, Iran, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, Turkey, and Israel might recognize that entrenched ways of working at cross-purposes with one another put the virus response and economic recovery at risk. The pivotal point with respect to conflict in this scenario is that each keeps that recognition within their own governments until the toll on the region is too great to continue that way.

At that tragic point, we could envision the governments beginning slowly to work together to build a structural and policy framework for resource sharing and collaboration to address public health risks at a regional level. Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey in particular would have strong incentive to do this, as they would want to preserve the hard-won economic gains that had finally begun materializing. And all presumably would recognize that, with the blunders in the response to the virus, they need to commit to ensuring that such a “common disaster” never happens again. Turkey, Iran, and the UAE might begin advocating for broadening the cooperative framework to encompass other issues that threaten the resilience and stability of the region. Saudi Arabia could be expected to reluctantly follow suit. Mechanisms to work together on the geopolitical front (encompassing not only inter- and intra-state conflict but also climate change adaptation, food security, and other issues) could begin to be built. By 2025, there would still be a long way to go. But given the history of rivalry and resistance to such efforts, the devastation envisioned in this scenario spurs progress. The imperative of course would be for the envisioning of such devastation to do so soon, before it becomes true in the real world.

"Conflict dynamics in the pre-pandemic Middle East reflected zero-sum thinking among the regional powers, other national actors, and international actors. ... COVID-19 changed this."

4. Conflict Dynamics — Looking Across the Scenarios

The conflict dynamics in these scenarios do not offer much room for optimism. “Together — for Now” and “Slow Burn” portend that the region might transition to at least some greater degree of stability, but there are also some counter-intuitive outcomes. In “Slow Burn,” the dearth of cooperation when it came to the public health response to COVID-19 was a wakeup call to populations and their governments in the aftermath of the pandemic. That scenario engendered a response similar to what happened in Europe at the end of World War II, when societies and governments, sobered by the destruction, forged ahead with the European Coal and Steel Community, the precursor to the European Union. It suggests that the right approach to building enduring cooperative regional health resilience mechanisms could gain some traction and evolve over time to a broader security architecture. In “Together — For Now,” while there is not the chastening of “Slow Burn,” there is at least an unstable equilibrium in the region upon which a security, health, and economic architecture might be built. But this is unlikely to occur without strong international support.

In the “Patients Yes, Patience No” and “Good Enough Isn’t” scenarios, despite the COVID crisis having been handled relatively well, we see suboptimal outcomes in terms of regional and civil war conflicts. This has much to do with the mismatch between government actions and societal expectations. In “Patients Yes, Patience No,” by 2025 an economic recovery traction develops, but it is just too late, and earlier efforts have created such income inequality that conflicts at all levels show an uptick. In “Good Enough Isn’t,” we have the opposite. Despite efforts to reduce the economic pain in the early years, by 2023 to 2025 momentum hasn’t taken hold or has been lost, with stark consequences. Among those consequences are renewed intra-societal sectarian, regional, and civil war conflicts that in some cases have even more complexities than they demonstrated in the years prior to the pandemic.

"To avoid the worst outcomes for an already fraught region, there is no substitute and frankly no alternative to some form of cooperation among regional actors, and ideally international actors as well."

5. Conclusion: Policy Considerations for Middle East Conflict in COVID-19’s Wake

The Middle East, historically heavily shaped by outside powers, has started in recent years to shape itself, albeit in a violent and destructive way. This turmoil is ongoing, at a moment now when COVID-19 has made the nations of the region more, not less, connected with each other and with the international community. Ameliorating the risks posed by the region’s deep-rooted and volatile conflicts in the face of the pandemic demands thoughtful policy and other actions at the national, regional, and global levels, all at the same time.

Our scenarios posit that any moves toward stability and comity between regional powers as the responses to COVID-19 play out will be tentative and fragile. They could be quite sensitive to the right — and the wrong — actions by the range of stakeholders in the region. Our view, “from 2025,” suggests these will be particularly important.

Recognize That We’re Playing Three-Dimensional Chess

The three dimensions we focus on in this paper with respect to the Middle East COVID-19 response each will have profound impacts on life in the region. The interrelationships between them are already playing out and are already on the radar of leaders, not only in the Middle East but around the world. Acknowledging those interrelationships, and recognizing the second- and third-order effects they have on conflict in the region, is simpler than managing and shaping them in an integrated way. But that is the imperative — crafting truly multi-dimensional response policies and action plans. It is essential that leaders not only think but also work, now, at the nexus of the health response to the virus, its impact on economies, the social dynamics complicated by the pandemic, and the region’s endemic conflicts.

For success against the pandemic and regional conflict to “trend” together in a positive, constructive way over the next few years, we see several keys. One is that efforts by regional and extra-regional actors in the health response dimension be pursued as not just a “stat” response to the virus. They must also be a purposefully designed and enduring improvement in the public health systems and infrastructure of every country in the region. Collaboration among these actors should also extend beyond the health care and health policy sector itself to their counterparts in the economic response and in the foreign policy and domestic security spheres. A degree of coordinated policymaking is apparent at the seam of health and economy. Work at the seams with foreign and domestic security policymakers isn’t — not necessarily because it isn’t happening, but it is at least not prominent, and it should be.

The importance of integrated approaches to the three dimensions is reinforced when we see in different scenarios how dependent the economic responses are on how the health response goes, and how social reactions lag both. One thing this suggests is how support from outside the region should be designed to free the countries of the region from wrenching dilemmas in their economic responses. Choosing between easing the impact on populations today at the potential expense of already-fragile fundamentals, putting at risk a solid long-term economic recovery, is potentially very destructive. Debt relief is one idea gaining attention that might preclude such choices. What the right policy decisions are, and by who, is beyond our expertise, but our analysis tells us that policies to put the region on a middle path between “triage” and “traction” are needed. It also tells us that governments in the region, local religious and sectarian leaders, and international actors (nations and institutions) must recognize the importance of giving one another the breathing space to let the economic measures move forward. Politicizing them, or using them as a prop to fuel longstanding unrelated grievances, will only undermine the integrated health, economic, and social policy response the region needs to stave off conflict.

Build Pandemic Response Collaboration Over Time into a “Regional Resilience Architecture”

In order for the Middle East to stabilize in and for a post-COVID era, there needs to be a strengthening of regional institutions. The eye should be toward a broad regional architecture that encompasses a multiplicity of issues and interests. Today this certainly seems a bridge too far. Cooperation on matters related to security, water, and climate has been elusive and the trendlines have moved in the wrong direction.

But the opportunity should be taken to build on the baby steps taken thus far in the response to the virus, like the UAE sending medical supplies to Iran at the beginning of the crisis.2 This and similar actions show the virus as a leveler appealing to common interests even of adversaries. Moving deliberately from steps like this as a “one-off” transaction to a structured, enduring system of such steps, would not only blunt the effects of more pessimistic COVID-19 scenarios. It would also build the resilience of public health infrastructures across the region against future pandemics and other risks, and build trust to undergird cooperation on other issues over time.

From there, sooner rather than later, the opportunity should be taken to build on cooperation on the health front to move toward a broader “architecture” encompassing security, economic, and other factors. In the past, this concept has centered only on security and other geopolitical concerns. The public health factor in a future regional cooperation framework will be essential — and may always have been. Now that health concerns are front and center for all in the region, they could be the missing link enabling such a framework to be considered in a new way. Framing it in terms of resilience — “the ability to adjust to deformation caused especially by compressive stress” — could help as well. The conflicts of the past 70 years are a “compressive stress” to which the region has been unable to adjust. Perhaps this is because efforts to create institutional mechanisms for doing so have only ever been framed in geopolitical terms that themselves carry an aura of competitiveness. If the scenarios show anything, it is that health, the economy, and security are inextricably linked. Working in an integrated way to strengthen them all is essential to elevating resilience over competition in the region.

While expecting this to happen in the short term is unrealistic, steps toward institutionalizing health cooperation could be used as a foundation for building broader forms of cooperation. An analogue may be the European Coal and Steel Community, which at the end of World War II laid the foundation for what became the European Union. It would be foolhardy to suggest that an EU-like structure could emerge in the Middle East. But the notion of using the response to COVID-19 as an opportunity to move in that direction is far from naïve.3

Hippocratic Foreign Policy — At Least for Now

In most of our scenarios, unsurprisingly, the relationships between the major regional powers — Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Israel — are pivotal. These relationships are a primary hinge determining not only how the region as a whole trends toward stability or conflict, but also the success of the pandemic response. The degree of cooperation or hostility between these powers also drives the civil wars in the region to either more or less intensity.

Right now the United States is doubling down on its effort to squeeze Iran, and seems to have given a very long leash to allies Saudi Arabia and Israel. This runs the risk of stoking, rather than reducing, regional power hostilities, and thereby in a very real way undermining the response to COVID-19. And the scenarios suggest that a conflictual or self-interested response to the pandemic will in turn further fuel conflict, in a vicious circle. While it is important to maintain U.S. alliances in the region, there needs to be a greater willingness in Washington’s and other powers’ foreign policies to “do no harm.” Deployment of pressure tactics against Iran with no diplomatic pathway runs a risk of reinforcing bad Iranian (and Saudi and Israeli) behavior, and increasing the risk of bad COVID-19 outcomes. The hostilities between the United States and Iran also are taking place in Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria, countries that are bearing the brunt of weak governments, restive populations, and a looming COVID disaster. Foreign policy that encourages cooperation among the regional powers may be beyond the proclivities of at least some current leaders. But to avoid the worst scenarios and push the future toward the more optimistic ones, it is essential to at least take the foot off the accelerator in ongoing clashes.

In Sum

To avoid the worst outcomes for an already fraught region, there is no substitute and frankly no alternative to some form of cooperation among regional actors, and ideally international actors as well. With the Middle East likely to emerge from the COVID-19 crisis more fragile and potentially explosive than before, a cooperative architecture that can build regional resilience is an imperative. Policymakers should look at some of the scenarios outlined above as both a wakeup call and an opportunity to move toward such an architecture.

Steven Kenney is a non-resident scholar at MEI and the founder and principal of Foresight Vector LLC. Ross Harrison is a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute and is on the faculty of the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University and the political science department at the University of Pittsburgh. The views expressed in this piece are their own.

Photo by Amru Salahuddien/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Endnotes

1. With COVID-19 related events moving so quickly, the environmental scan we are conducting to inform this analysis, and other elements of our MENA foresight studies, is in its formative stages. Leveraging that work-to-date, these are our current hypotheses about how the responses to the pandemic will cause or contribute to change in conflict dynamics in the region.

2. “UAE Sends Medical Aid to Iran as Coronavirus Outbreak Intensifies,” Al-Monitor, March 17, 2020, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2020/03/uae-iran-medical-aid….

3. See “Toward A Regional Framework for the Middle East: Takeaways from Other Regions” in Ross Harrison and Paul Salem, From Chaos to Cooperation: Toward Regional Order in the Middle East (MEI Press, Washington, DC): 2017